Amanda Clement

“Can you suggest a single reason why all the baseball umpires should not be women? Of course you can’t. I mean just what I say, seriously, that all the official baseball umpires of the country should be women.”1 A statement that the baseball world has long disagreed with but was stated in 1906 by a young Amanda Clement, the first female to be paid to umpire. She “is an example of what a woman can do even in a sphere that seems to be entirely out of range of the fair sex.”2

“Can you suggest a single reason why all the baseball umpires should not be women? Of course you can’t. I mean just what I say, seriously, that all the official baseball umpires of the country should be women.”1 A statement that the baseball world has long disagreed with but was stated in 1906 by a young Amanda Clement, the first female to be paid to umpire. She “is an example of what a woman can do even in a sphere that seems to be entirely out of range of the fair sex.”2

Amanda Clement was born on March 20, 1888, in Hudson, Dakota Territory, a year before South Dakota became a state. Growing up with her brother Allen (better known as Hank) gave Clement the chance to play sports and learn the rules. Her mother, Harriett, raised the two alone after Amanda’s father died when she was a little girl. The family lived near the local ballpark and so Amanda and her brother spent a great deal of time there. Accompanying her brother to his games, Amanda often found herself umpiring the sandlot games, since girls did not play baseball with any regularity. However, when the boys asked her to fill in, she occasionally played a little first base, which helped her learn the game.

One day, after Amanda traveled with her mother to Harden, Iowa, to watch Hank’s Renville team play a semipro game against Hawarden, history was made. The umpire did not show up for the preliminary game and her brother volunteered his sister. And when the umpire did not arrive for the scheduled contest, the teams accepted her after having seen her umpire. And so in 1904 Amanda Clement became the first woman paid to umpire a game. The teams actually had to persuade her mother to let her umpire since this was not something young ladies did. Clement put any doubts to rest immediately and began a successful career as an umpire for six years, traveling across the upper Midwest, umpiring about 50 games a summer. Earning between $15 and $25 a game, Clement earned enough money each summer to put herself through college. Baseball was hugely popular at the time; there was little else to draw away people’s attention. Every small town had a ballclub and games were a constant with town pride at stake. Umpires were in demand and Clement benefited from that need. At this time umpires generally worked alone, calling balls and strikes from behind the pitching mound. This gave the umpire a better view of all the action on the bases as well. For Clement this also meant she was not as close to the fans as she would have been behind the plate.

Since this was a time when women were not encouraged in such public pursuits, Clement became a novelty during the six years she umpired. The woman’s place was still at home, taking care of the household. Clement was so good at her job, however, that she got calls from all over the Midwest to umpire. One paper described her as “possessor of an eagle eye, seldom makes a mistake.”3 Promoters quickly came to realize that a young female umpire who was good at what she did would attract more fans and so Clement was in demand. One newspaper reporter claimed she even received more than 60 marriage proposals from across the country as her reputation grew. In response to one young man’s overtures, Clement told him, “I’m wedded to baseball.”4

Clement’s reputation grew with each game she umpired. She was in such demand during the summers that she often had to make choices about which games she would umpire. Many communities invited her back after seeing her work. As one reporter said, “But see her once, mask on, behind the catcher and hear her call the balls and strikes, and at once you reach the conclusion that a young woman of skill, judgment and determination is performing with marked ability.”5 Clement did miss a few weeks in the summer of 1910 after she injured her left knee while playing catch. She had to wear a plaster cast and then walked with a cane for a few weeks.

On one occasion in South Dakota, Clement was introduced to President Teddy Roosevelt, who told her he had heard of her already. A local writer, Will Chamberlain, wrote a poem about the lady in blue in 1905. After a game between Gayville and Garretson, the local paper reported, “She umpired the game as quietly and easily as other young women would sweep a floor or make a cake.”6 Clement’s umpiring took her all over the Midwest. One week might find her umpiring a game in Sioux City and the next in Elk Point, South Dakota, or Brookings, or Minneapolis. One of the most interesting games recorded that Clement umpired was one in Tekamah, Nebraska, between the White Sox and a colored team from Omaha called the Midway.7

Clement had few problems on the diamond or on the road as she traveled across the Midwest. A Congregationalist, she often stayed with local ministers’ families and would not umpire on Sundays. Further supporting the idea that Clement did not compromise her femininity or her morals by working as an umpire, she was invited to speak from the pulpit at a local church in Rock Rapids, Iowa. Afterward she spoke at the high school on “The Value of Athletics.” She even walked off the field once when one of the players, Toots Thompson, used profanity. She refused to umpire any games Thompson played in after that. She remained convinced that having female umpires would truly clean up the game since at that time it was unacceptable for a gentleman to publicly insult a lady. “Now if women were umpiring, none of this would happen,” she said. “Do you suppose any ball player, in the country would step up to a good-looking girl and say to her, ‘(Y)ou color-blind, pickle-brained, cross-eyed idiot, if you don’t stop throwing the soup into me, I will distribute your features all over this ground until the janitor will be compelled to soak you up with gasoline?’ Of course, he wouldn’t. Ball players aren’t a bad lot. In fact, my experience is that they have more than the usual allowance of chivalry. And I don’t believe there’s anybody in the country that would speak rudely to a woman umpire, even if he thought his drive was ‘safe by a mile’ instead of a foul.”8 In fact, a friend said players were likely to say, “Beg your pardon, Miss Umpire, but wasn’t that one a bit high”9 She was also not afraid to eject a player in order to maintain control of the game. Clement believed she ejected about six players over the years.10

Clement also believed the fear that a female umpire was more likely to be assaulted or mistreated than a man was overplayed. “Then there’s the crowd,” she said. “There’s a good deal of cowardice about the roasting of umpires by crowds, because hardly any of the fans that shout all sorts of insults from the bleachers would have the nerve to say anything of the kind to the umpire’s face.”11

Not all the teams or reporters were kind to Clement. Some of them clearly followed the attitude of the time, believing that women belonged at home and not out in public. One reporter made his feelings quite clear, stating, “The female umpire, the bloomer girl ballplayer and the dodo bird can be spared very nicely. A woman in bloomers isn’t an inspiring sight, anyway.”12 Another individual, Brother Sturges of the Bereford Republic, chastised Clement for her athletic endeavors and claimed that the only thing anyone one cared about was her ability to make a proper meal or sew her own clothes. In other words, tasks accepted at the time as womanly. The people of Clement’s hometown responded to this attack with great support, saying, “Miss Clement is not a paragon. She is simply a young woman who loves athletics and who is paying her way through college with what she earns during the summer working as an umpire, for she is not only perfecting herself in physical culture …but she is also desirous to perfect herself in the study of medicine, as it has ever been her ambition to become a doctor, and it costs money to go to college.”13

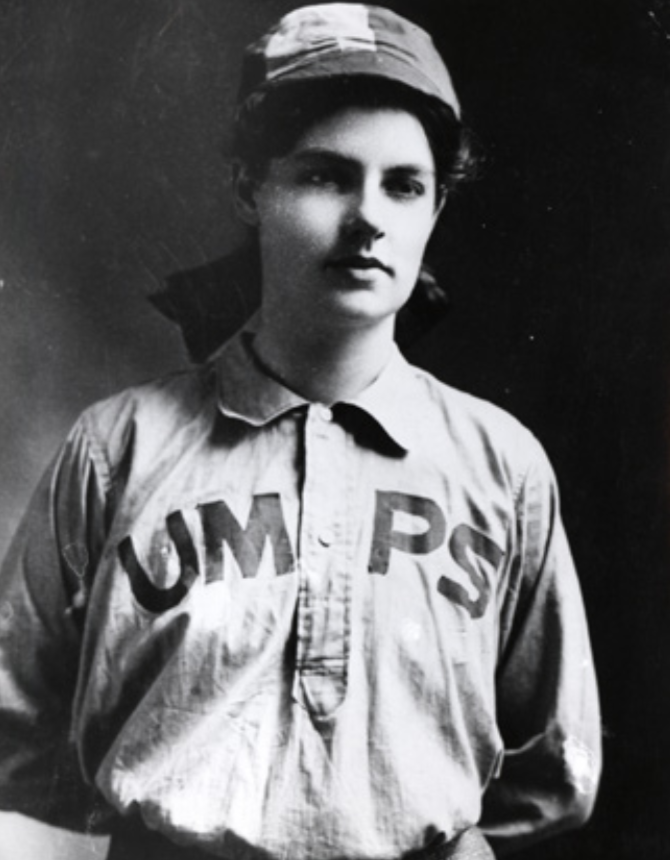

From 1904 to 1911 Clement regularly umpired about 50 games a season in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Iowa. Billed as “The World Champion Woman Umpire,” she appeared on the diamond wearing “a full-length blue skirt, black necktie, white blouse with UMPS stenciled across the front of a peaked cap.”14

Clement saved a portion of her umpiring earnings, $15 to $25 a game, to finance her education. She studied at Yankton Academy for two years, then Yankton College for two years and finally finished at the University of Nebraska, graduating in 1909. While in college Clement played basketball and tennis, ran track, and worked for the local newspaper. One game reported in the paper had Clement’s Yankton Academy basketball team winning 15-1 while listing her as the star player. The college hired her to umpire the club team, hoping her presence would stop some of the “rowdyism” through her “good judgment and fine mind.”15 She also refereed local high-school basketball games. This has raised speculation that in addition to being the first paid female umpire, Clement might have also been the first female referee. There were also many stories published about records she set in different sports, most of which were more rumor and legend than fact. She did, however, set a national record for females throwing a baseball, 275 feet. She broke the existing record, set by a young woman from Chicago, by five feet. She also won a vase in a “Carrie Nation Hatchet Throwing Contest.”16

Clement’s college degree in physical education let her work as a teacher and professor throughout her professional career. She taught for a time at the University of Wyoming as well as for four years at Jamestown, North Dakota, High School. In addition she also worked at the YWCA in La Crosse, Wisconsin. While in La Crosse one of Clement’s projects was to show how the footwear forced on young ladies deformed their feet. Clement took photos of the feet of 75 young women with and without their shoes and put the pictures on display, hoping this might force some changes. She also gave swimming lessons and helped save a man’s life after he nearly drowned in the local river. After he was pulled out of the river, Clement administered mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.17 From her experience playing college basketball, she later coached an independent basketball team in Hudson and even refereed high-school basketball –perhaps the first woman to do so.18

Clement, who never married, moved home in 1929 to take care of her ill mother. She then moved to Sioux Falls in 1934 after her mother died and she worked as a social worker for 25 years, overseeing both the city and county welfare divisions, until her retirement in 1966. Until her death in Sioux Falls on July 20, 1971, she remained an ardent fan of the game that got her started in life, rooting for the Minnesota Twins.

In recognition of her many athletic accomplishments, Clement was elected to the South Dakota Sports Hall of Fame in 1964. In 2014 she was inducted into the Yankton College Alumni Hall of Fame. A children’s book, Umpire in a Skirt: The Amanda Clement Story (2010), by Marilyn Kratz, tells her incredible story for the generations to come.19 Clement loved the game and never saw umpiring as something ladies should not do. “There is no reason why a young woman cannot make a business of umpiring and be a perfect lady,” she said. “I maintain that it is just as womanly as it is to play tennis.”20

This biography is included in “The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 “One Who Made a Big Success Tells of the Work,” Pittsburgh Press, September 17, 1906.

2 Amanda Clement Hall of Fame File, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York. See also Sharon L. Roan, “No One Yelled “Kill The Ump” When Amanda Clement Was a Man in Blue, Sports Illustrated, April 5, 1982, and Colin Kapitan, “Nobody Yelled ‘Kill the Umpire!’” South Dakota Magazine, July 1985.

3 “Woman as Umpire,” Meriden Daily Journal, June 20, 1906.

4 “Players All in Love With Girl Umpire,” Reading Eagle, August 26, 1906.

5 “Girl Baseball Ump,” Reading Eagle, June 29, 1906.

6 Clement Scrapbook, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

7 Hall of Fame file.

8 Pittsburgh Press, September 17, 1906.

9 Kapitan, “Nobody Yelled ‘Kill the Umpire!’”

10 “A Girl Umpire,” Sporting Life (Vol. 46, No. 4), October 7, 1905: 8.

11 Pittsburgh Press, September 17, 1906.

12 Pittsburgh Press, January 22, 1906.

13 Sioux City Journal, n.d., Hall of Fame file.

14 Kapitan, “Nobody Yelled ‘Kill the Umpire!’”

15 “Would Wed Ump,” Sporting Life, Vol. 47, No. 20, 1906.

16 Will Talsey, “The Umpire Was a Lady,” Baseball Magazine, October 1952: 31.

17 Clement Scrapbook, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

18 “South Dakota Woman Is Jack of All Trades,” Ludington (Michigan) Daily News, April 7, 1929; “150 Feet to the Bad,” The Gazette Times, June 10, 1913.

19 “Sioux Falls Woman Recognized in Yankton as Baseball’s First Female Umpire,” Associated Press, July 21, 2014.

20 Amanda Clement File, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

Amanda E. Clement

Born

March 20, 1888 at Hudson, SD (US)

Died

July 20, 1971 at Sioux Falls, SD (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.