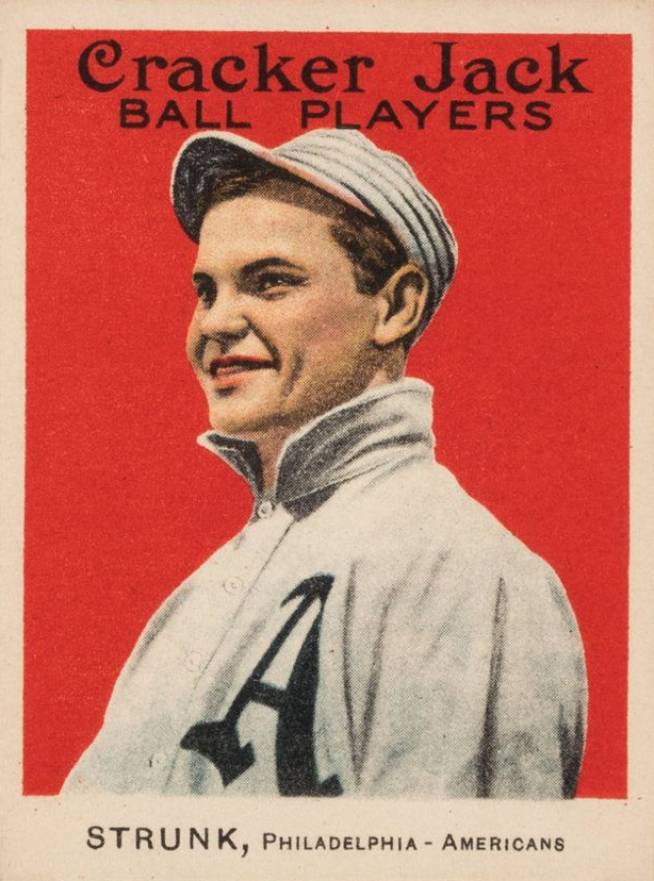

Amos Strunk

Lanky and lightning fast, Amos Strunk was one of the best defensive center fielders of the Deadball Era and a major offensive contributor to Connie Mack‘s powerhouse Philadelphia Athletics teams which appeared in four World Series from 1910 to 1914. A patient hitter, the left-handed Strunk placed in the top 10 in the American League in slugging three times from 1913 to 1916, but his power was a derivative of his speed: though “The Flying Foot” never became a great base-stealer, he was one of the fastest in the league on the basepaths, placing among the league leaders in doubles twice and triples four times. Strunk’s exceptional speed allowed him to go from first to third on bunt plays, and his quickness led J.C. Kofoed of Baseball Magazine to remark: “Some call him the Mercury of the American League, but all know Amos Strunk whatever the handle they plaster on him. He is of a type one instinctively calls rangy, because he moves with the speed you would exert should you accidentally touch a red-hot range.”

Lanky and lightning fast, Amos Strunk was one of the best defensive center fielders of the Deadball Era and a major offensive contributor to Connie Mack‘s powerhouse Philadelphia Athletics teams which appeared in four World Series from 1910 to 1914. A patient hitter, the left-handed Strunk placed in the top 10 in the American League in slugging three times from 1913 to 1916, but his power was a derivative of his speed: though “The Flying Foot” never became a great base-stealer, he was one of the fastest in the league on the basepaths, placing among the league leaders in doubles twice and triples four times. Strunk’s exceptional speed allowed him to go from first to third on bunt plays, and his quickness led J.C. Kofoed of Baseball Magazine to remark: “Some call him the Mercury of the American League, but all know Amos Strunk whatever the handle they plaster on him. He is of a type one instinctively calls rangy, because he moves with the speed you would exert should you accidentally touch a red-hot range.”

Amos Aaron Strunk was born on January 22, 1889, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the fifth child of Amos, a carpenter, and Amanda Strunk. Young Amos learned baseball playing at Fairmount and Huntington Parks in Philadelphia, where the players were called “Park Sparrows” since they spent so much time on the baseball field. There, it was noted that “the lanky kid was too fast for his protagonists. He ran rings around them, and they confessed it.” After playing with an amateur team in Merchantville, N.J. in 1907, Strunk began playing professionally with Shamokin of the outlaw Atlantic League in 1908. From there, he was recommended by teammate Lave Cross to Athletics manager Connie Mack, who brought Strunk to the major league team and played him for the first time on September 24, 1908; Strunk collected a pinch hit single in his debut. Mack was intent on assembling a group of speedy players, and “he wanted men who could travel fast enough to burn their galoshes. [Eddie] Collins, [Jack] Barry, [Rube] Oldring, and the rest were in that class, and Amos fitted in like a drink on an August day.” Strunk was sent out to Milwaukee of the American Association for some additional seasoning early in the 1909 season, but he was soon back with Philadelphia to resume a major league career that would last for 17 seasons.

At age 21 in 1910, the 175-pound Strunk was described as being “built like a panther, standing six feet in height, and without an ounce of superfluous flesh upon him.” Strunk, however, played in only 16 regular season games in 1910 due to a knee injury. Strunk was plagued by injuries throughout his career, which is a major reason why he played in fewer than 100 games in eight of his major league seasons. Strunk came back late in the season and played in four of the five games in that year’s World Series, collecting five hits in 18 at-bats and driving in two runs.

Strunk quickly established himself as one of the premier defensive outfielders in baseball. In 1913, one writer claimed that “Amos has justly earned the verdict of being the greatest defensive outfielder that the game has ever produced. In the matter of fielding his position on the defense, the Ty Cobbs of today and the Curt Welches of other days never even approximated the same class displayed by Amos. It is impossible to even conceive of anything in human form performing more sensational and unerring feats than Amos shows consistently day in and day out. An accurate judge of a batted ball, off at the crack of the bat, his great speed takes him to wallops that other great outfielders would never reach, and he has no weaknesses to either side, in front or back there, by the palings.” Baseball Magazine three years later noted that “for five years now Amos has demonstrated to his fellow townsmen that, barring a few immortals like Cobb and [Tris] Speaker, he need doff his chapeau to none.” High praise to be sure, but Strunk elicited it through his superlative play, leading the league in fielding percentage four times from 1912 to 1918, and regularly ranking among the league leaders in putouts per game. Despite such accolades from the press, Mack felt his center fielder was undervalued, calling Strunk “the most underrated outfielder in baseball.” Mack went on to say that “Amos made his job of playing center field look a lot easier than it really was.”

Strunk was also a key man in Mack’s famed double squeeze play. With Strunk on second and a runner on third, Mack would have the batter bunt. The speedy Strunk would break from second base with the pitch and would follow the runner from third home, allowing the Athletics to score two runs on a single squeeze bunt. In addition to the 1910 championship team, Strunk was a major contributor to Connie Mack’s World Series teams in 1911, 1913, and 1914, though injuries kept him from appearing in more than 122 games in any of the three seasons.

During his career, Strunk was considered one of baseball’s great storytellers. It was said that he had a “De Wolfe [sic] Hopper way of telling stories,” in reference to the legendary Broadway actor and orator. Baseball Magazine commented: “Some time when you’re not busy get Amos to tell you stories on old John McCluskey. He’ll make you laugh so hard you’ll lose your wrist watch.”

Strunk did not enjoy his best season in a Philadelphia uniform until Mack had dismantled the A’s dynasty, selling off most of the team’s best players and sending the club plummeting in the standings. In 1916, when the A’s lost an astounding 117 games–still the worst record in modern baseball history–Strunk was by far the team’s best player, setting career highs in doubles (30), hits (172), and on-base percentage (.393), while ranking fourth in the league with a .316 batting average. He followed that performance with another strong campaign in 1917, scoring a career-high 83 runs while batting .281 with a .363 OBP. Following the season, the cash-strapped Mack completed his fire sale, sending Strunk, Joe Bush, and Wally Schang to the Boston Red Sox in return for $60,000 cash and three players.

Strunk’s average slipped to .257 in 1918, as the Red Sox captured the pennant and won the World Series. In June 1919, Strunk was traded back to the Athletics from the Red Sox along with Jack Barry in return for Bobby Roth and Red Shannon. Claimed off waivers by the White Sox in July 1920, Strunk had another outstanding season in 1921 with Chicago, and he went on to play primarily a part-time role with the White Sox through 1923. Though Strunk continued to be effective when he played, persistent leg injuries often kept him on the bench and chipped away at his defensive range. In 1922, Strunk batted .289 in 92 games, and in 1923 he posted a .315 batting average in 54 at-bats. During spring training 1924 Strunk suffered serious head injuries in an outfield collision with teammate Roy Elsh, and was released by the White Sox a month later after appearing in only one game as a pinch hitter. On May 2, 1924, the Athletics acquired him for a third time, signing the 35-year-old outfielder as a free agent. In 30 games for the Athletics, Strunk posted a .143 batting average and was released at season’s end. Appointed as the player-manager of the Shamokin Shammies of the New York-Pennsylvania League in 1925, Strunk resigned in August, citing recurrent leg injuries, although he was batting .396 at the time. It was his last job in organized baseball.

In retirement, Strunk became an insurance broker, and he remained in that business for 50 years. He was also an expert photographer. A 1958 article described how “Strunk might be taken for a retired admiral. His hair is white, and he is youthful in movement and dress.” His wife Ethel, whom he married in 1915, was a successful portrait painter, and the two were married for more than 50 years until her death in 1966.

Strunk occasionally bemoaned the lack of aggressiveness in contemporary baseball after he retired. He felt that baseball needed more of the competitive fire that teams like the Dodgers and Giants showed during Strunk’s era. “Baseball needs more of that bitterness today,” he said, “but it’s still a wonderful game.”

Amos Strunk died on July 22, 1979, at age 90 in Llanerch, Pennsylvania after a brief illness. He was survived by two nephews. Strunk was buried in Greenmount Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Sources

Unattributed clippings from Strunk’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Dell, John. “Whatever Happened to Amos Strunk?” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 25, 1973

Kofoed, J.C. “The Fable of the Flying Feet: Amos Strunk, Star Outfielder of the Athletics, and How Speed Has Been the Watchword of His Career,” Baseball Magazine. August 1916. Volume 17, Number 4, pages 33-35.

Williams, Edgar. “Obituaries: Amos Strunk, 89, outfielder for pennant-winning Athletics.” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 26, 1979.

Yeutter, Frank, “Incident in Life of A’s Old Timer: Amos Strunk Won Baseball Fame After ‘Jumping’ S. Carolina Team” Bulletin, March 3, 1958.

Full Name

Amos Aaron Strunk

Born

January 22, 1889 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

July 22, 1979 at Llanerch, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.