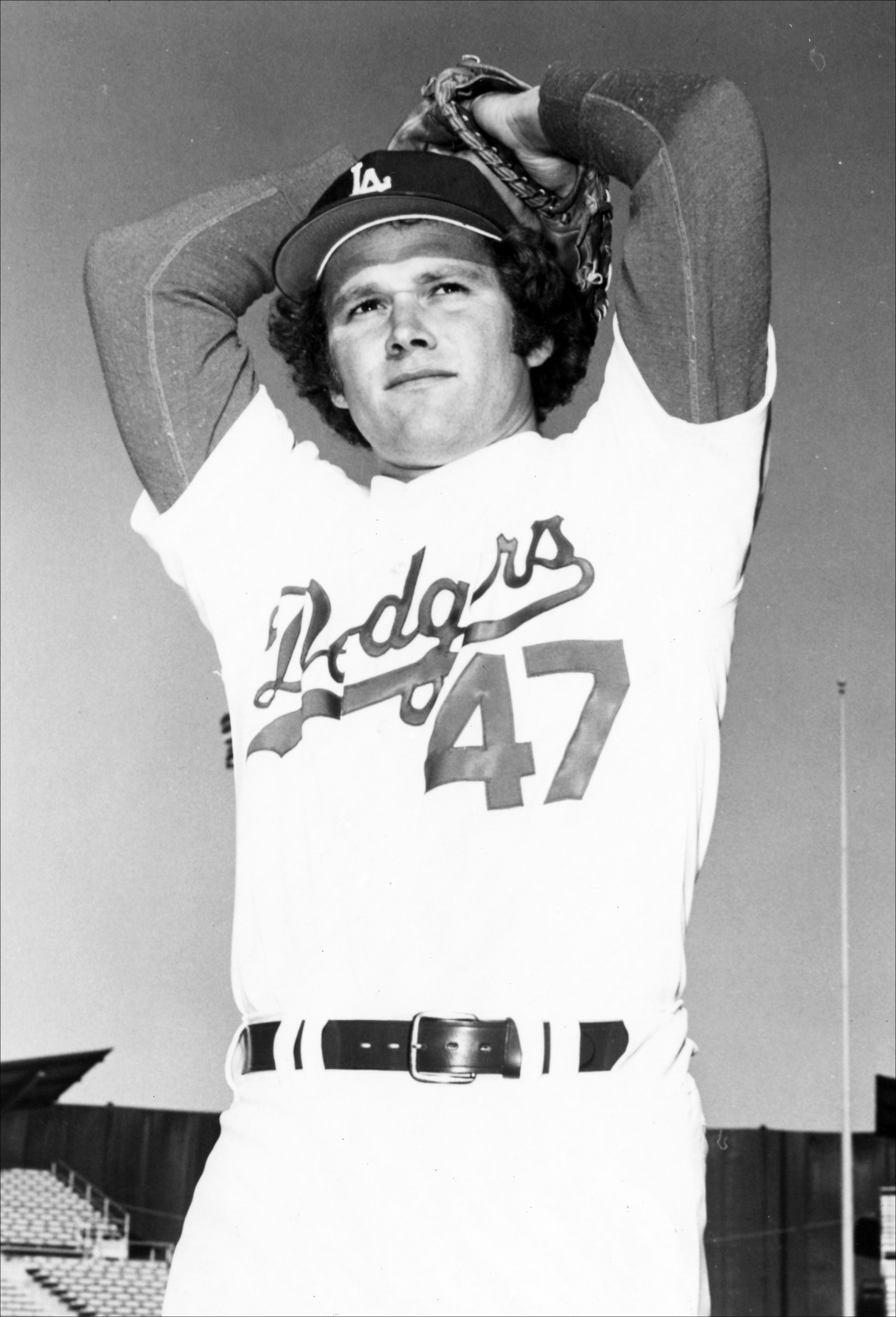

Andy Messersmith

August 27, 1968. Yankee Stadium. Bottom of the sixth. Angels 1, Yankees 0. Bases loaded, two out. The crowd of 21,419 lets out a tremendous roar as Mickey Mantle is called upon to pinch hit. Although it was the last year of The Mick’s career, he’d already hit 16 homers and was still a threat to go yard.

August 27, 1968. Yankee Stadium. Bottom of the sixth. Angels 1, Yankees 0. Bases loaded, two out. The crowd of 21,419 lets out a tremendous roar as Mickey Mantle is called upon to pinch hit. Although it was the last year of The Mick’s career, he’d already hit 16 homers and was still a threat to go yard.

Because the visiting team bullpen was in the corner of left field, the 23-year-old rookie relief pitcher the Angels had summoned to preserve the lead did not know he would be facing his lifetime idol until he saw him swinging bats beside the plate. Five pitches later, the Angels’ Andy Messersmith retired the revered Mantle on a swinging third strike fastball. Awed but not intimidated, the young pitcher demonstrated what became his trademark commitment: giving his utmost under any circumstances.

To many baseball fans, Andy Messersmith is best remembered for his role in dismantling Major League Baseball’s much despised (except by team owners) reserve clause, thus enabling players to have a say in their employment status. What is often overlooked is that in his 12-year major-league career, Messersmith was one of the most respected, liked, and successful pitchers in baseball: twice a 20-game winner, four times an All-Star, two times a Gold Glove recipient, and three times a contender for the Cy Young Award. Messersmith’s career 2.86 ERA is the sixth lowest among starting pitchers whose careers began after the advent of the Live Ball Era in 1920. He is sixth on the all-time list of pitchers surrendering the fewest hits per nine innings.

John Alexander “Andy” Messersmith was born on August 6, 1945, in Toms River, New Jersey. His mother and physician father moved the family to Orange County, California, when Andy was 5 years old. Andy attended Western High School in Anaheim, alma mater of Tiger Woods and 2013 Nobel Prize-winning biologist Randy Schekman. At Western High Andy quarterbacked the football team and pitched on the baseball team. And like so many others who have grown up in Orange County, Andy surfed.

One of the biggest influences on Messersmith’s baseball career occurred in his junior year in high school when his baseball coach, Dave Hernandez, taught him to throw a slider. He quickly mastered the pitch and became a dominant high-school pitcher. As a junior he went 4-1. In his senior year, Mesersmith won 16 games and lost 2, leading his team to second place in the California Interscholastic Federation Southern Division championship.

In the fall of 1963 Messersmith enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, on a full baseball scholarship. In his sophomore year (8-2, 1.63 ERA) Messersmith was named second team college All-America and first team All-California Intercollegiate Baseball Association and All-NCAA District 8. At the end of the 1965 collegiate season the Detroit Tigers drafted him but he returned to college instead of signing. In the June 1966 draft, Messersmith was chosen in the first round by the California Angels. The Angels’ scouting report read, “He’s got three pitches – two of ’em you can’t hit and the other one you can’t even catch.”1 On June 11, 1966, Messersmith signed with the Angels, 20 credits shy of finishing his college degree.

The Angels sent Messersmith to Seattle in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, where he won four games and lost 6. In 1967 he was with El Paso in the Double-A Texas League, and at the beginning of the 1968 season he was back with Seattle. On July 2 Messersmith was called up to the Angels, who had high hopes for the 6-foot-1, 200-pound, 23-year-old of whom Angels manager Bill Rigney said, “This fellow has the potential to be the very best pitcher in the league.”2

In that half-season season with the Angels, Messersmith pitched in 28 games, 23 in relief, which Rigney explained was a necessity. “He deserves a chance to start,” said Rigney, “but he’s been of such value in our bullpen that taking him away from it would be a handicap. Andy’s future will be as a starter, though.”3 Rigney’s prediction came to pass on September 6, 1968, when Messersmith started for the first time, beating the Boston Red Sox 4-0 with a two-hit shutout. He finished the season with a 4-2 record and a 2.21 ERA in 81 innings of work, 74 strikeouts, and a WHIP (walks plus hits per inning pitched) of 0.97.

The year 1968 was also significant for Messersmith because, for the first time in history, major-league players had negotiated a collective-bargaining agreement with the team owners. The agreement included a grievance and arbitration procedure to settle contract disputes. But from the players’ point of view the arbitration procedure was close to worthless because the arbitrator was the commissioner of baseball, an employee of the owners. Nevertheless, it set a precedent: Players had the right to negotiate the terms of their contracts rather than being forced to accept what was set forth by management. Messersmith took the rights of players seriously enough to become the Angels’ alternate player representative to the players union, the Major League Baseball Players Association.

In 1969 Messersmith broke into the Angels’ starting rotation, appearing in 40 games, pitching 250 innings with a 16-11 record, 2.52 ERA, and 211 strikeouts. At 24 years old, Messersmith was making his mark. Opposing managers, including Billy Martin, credited Messersmith with “the best stuff” in the league.4

In 1970 Messersmith suffered a shoulder injury from a slide, pitched four months with damaged ribs, and had an off year, going 11-10 in 37 games (26 as a starter). In 1971, injuries repaired and pitching for a club with the ninth-best record in the 12-team league, Messersmith recorded the first of his two 20-win seasons (against 13 losses). He started 38 games, pitched 276 2/3 innings with a 2.99 ERA, and 179 strikeouts. He was selected to the All-Star team and was fifth in Cy Young Award voting. He also hit two home runs. Messersmith took pride in his hitting, and multi-hit games were not uncommon for him.5

At the end of the 1971 season, after posting a three-year (1969-1971) record of 47 wins and 34 losses. Messersmith’s position as a top-notch pitcher seemed assured. However, in 1972 his effectiveness declined precipitously due to a finger injury on his pitching hand that required surgery to repair. Messersmith finished the year with an 8-11 record but a respectable 2.81 ERA.

In January 1973 Messersmith heard on the radio that he had been traded to the Dodgers. The trade wasn’t particularly surprising since Nolan Ryan had arrived to be the Angels’ new staff ace, but the trade raised eyebrows because the Dodgers were already deep with good starting pitching. Messersmith and third baseman Ken McMullen went to the Dodgers for five players, including Frank Robinson.

In 1973, Messersmith’s first season with the Dodgers, the team finished second (95-66), 3½ games behind the Western Division champion Reds. Now strictly a starter, Messersmith posted a 14-10 record in 249 2/3 innings of work with a 2.70 ERA, a WHIP of 1.093 (fourth in the majors), and 177 strikeouts.

As the Dodgers won the National League pennant in 1974, Messersmith won a league-leading 20 games with only 6 losses in 292 1/3 innings of work. He had a 2.59 ERA and 221 strikeouts (second in the league). He was the starting pitcher in the All-Star Game, second in Cy Young voting (behind Dodgers teammate Mike Marshall), and a Gold Glove recipient. He lost his two World Series starts as the Dodgers fell to the Oakland A’s in five games. Dodgers manager Walter Alston could not have been more laudatory. “He’s one of the best competitors I’ve ever managed,” the manager said before the World Series. “He can do it all. He can pitch, field his position, has a good move to first, and isn’t the worst hitter in this league by any means. … Andy is the kind of guy who wants the baseball. He wants to pitch and that’s why I put him up there with the other great pitchers I’ve had the good fortune to manage.6

Of awesome personal performances Messersmith remarked, “Statistics are overrated. Championships are won in the clubhouse. You’ve got to like each other. You’ve got to play for each other, but first you’ve got to pull for each other. It’s not enough to have it one day, but be thinking of yourself the next. (Players) have different emotions, but when they walk into the clubhouse, each of them has to swallow his individualism.”7

For the ’75 season the Dodgers offered to increase Messersmith’s salary from $100,000 to $115,000, an amount commensurate with the earnings of top players at that time. Messersmith accepted the pay increase but he declined to sign a new contract because he wanted the team also to agree not to trade him, or if they did, he had the right to determine which team it would be. The Dodgers rejected Messersmith’s no-trade demand. Messersmith wanted to continue playing for the Dodgers, which is the reason he wanted the no-trade agreement in the first place, so he chose to hold out in the hopes that he and the Dodgers would agree to terms.

As a holdout, Messersmith pitched under tremendous pressure, and by his own account better than ever. “I’m very proud of the season,” he said in summing up his campaign. “This has been my best year. Both from a physical and performance standpoint. … The hardest part was pitching with the unsigned contract hanging over my head. Believe me, it’s difficult thing playing out one’s option. I felt a lot of mental pressure.”8 Messersmith finished the season with a 19-14 record in a league-high 40 starts while completing 19 games (also most in the league) with a 2.29 ERA in 321 2/3 innings of work. He struck out 213 and led the league with an average of 6.8 hits per nine innings pitched. He was selected for the All-Star team, was fifth in the Cy Young Award voting, and was a Gold Glove recipient.

By late summer of 1975 Messersmith and the Dodgers still had not agreed on the terms of the coming year’s contract and negotiations with the Dodgers had soured. After seeking advice from the players union he filed a grievance against the Dodgers and took his situation to binding arbitration. The issue under arbitration could not have been Messersmith’s no-trade demand since the Dodgers had no contractual obligation to consider it. Instead, he singled out the reserve clause, which bound a player to a team. Under the reserve clause, if a player did not accept a team’s contract offer, he would have to play under the terms of the old contract until the team traded or released him. Since team owners agreed among themselves not to hire players who did not sign their team’s annual contract offer, a player’s only choice was to accept the terms of an offered contract or quit major-league baseball.

Perhaps fearful of losing in arbitration, the Dodgers offered Messersmith a contract in which he would earn $480,000 over three years. Messersmith turned down the offer, saying “I’ve come this far. I need to see it through. There’s no reason why a club should be entitled to renew a player’s contract year after year if the player refuses to sign and wants to go elsewhere. I thought about it for a long time and I didn’t do it necessarily for me, because I’m making a lot of money. I didn’t want people to think, ‘Well, here’s a guy in involuntary servitude at $115,000 a year.’ That’s a lot of bull. But then, when you stop and think about the players who have nowhere to go and no recourse … this isn’t for a guy like me or any other established ballplayer unless you’re having problems with your owner or something like that. It’s more for the guy who is sitting on the bench and who believes he hasn’t been given a chance.”9

The arbitration took place at the end of November 1975. Pitcher Dave McNally was involved in a contract dispute with the Montreal Expos. McNally was on the brink of retiring but held back to join Messersmith in his challenge to the reserve clause. McNally said that getting rid of the reserve clause was getting rid of ownership of the players.10

At issue was the interpretation of the word “one” in Clause 10A of the standard players contract. It said, the team “shall have the right … to renew this contract for the period of one year on the same terms.” Messersmith and McNally’s representative, Dick Moss, argued that this meant a player’s contract could be renewed without his consent for only one year, after which the player would be free to sign with any team that wanted him. John Gaherin, the team owners’ representative, argued that the word “one” meant that an unsigned player remained an employee of a team for an unlimited number of one-year contracts.

On December 26, 1975, the neutral arbitrator, Peter Seitz, accepted the players’ contention that one year means one year, and as a result, Messersmith and McNally have gone down in baseball history as the men who killed the reserve clause. Most baseball historians say, however, that the actual slayer was Marvin Miller, the executive director of the Players Association. Miller delivered a decisive blow to the reserve clause in the 1970 Collective Bargaining Agreement when he got the owners to agree to neutral third-party binding arbitration.11 Some have suggested that Miller pushed Messersmith to seek arbitration, but Messersmith denied it. “You can’t lay it off on anyone else,” he said. “Everything you do is your doing. I could lay it off on the Players Association leaders but that’s not the truth. I was there. I did it.”12

After the arbitration decision, it was expected that Messersmith would be pursued and offered lucrative contracts by many teams. The year before, the A’s were found in violation of pitcher Catfish Hunter’s contract, making him a free agent. Hunter made $100,000 in 1974, his final year with the A’s. After he became a free agent, the Yankees signed Hunter for $3.35 million over five years with a three-year no-trade agreement. Messersmith was considered to be one of the best pitchers in baseball. What was his new contract going to be worth?

Contrary to expectation, a host of suitors did not come knocking on Messersmith’s door. After his 1973-75 run with the Dodgers, no team questioned Messersmith’s value as a player. However, the owners had decided not to enter a bidding contest for Messersmith as they had for Catfish Hunter. They feared that a big payout to Messersmith would lead to a massive escalation in salary costs as other players became free agents in subsequent years (a scenario that in fact came to pass). “Nobody would talk to me,” said Messersmith. “We called Cincinnati and they said I could play in Japan for all they cared.”13

As the start of the 1976 season approached, the Dodgers made an offer similar to what Messersmith had turned down prior to arbitration; he refused this offer as well. Other teams expressed interest but only the Yankees, Angels, and Padres put forth serious offers. And in each case the negotiations went ruinously south. With the 1976 season already two days old, Ted Turner, new owner of the Atlanta Braves, offered Messersmith $1 million over three years and a no-trade, no-cut agreement. Turner had offered Messersmith a contract months earlier but the parties were unable to reach a deal. Messersmith accepted Turner’s second offer and went to work for the Braves the next day. Though he had been working out at home during the frenzy of contract negotiations, he had no spring training and wasn’t ready for full-fledged competition. Consequently, Messersmith lost his first four starts with the Braves. But by mid-June he had improved his record to 5-5 on a team that was on track to finishing last in its division.

Messersmith’s 1976 statistics fell from their stratospheric heights with the Dodgers in the prior season. He was 11-11 in 28 starts, with 12 complete games and 207 1/3 innings pitched, a 3.04 ERA, and 135 strikeouts. He attributed his subpar year to a set of harsh injuries. (A leg injury kept him out of the All-Star game.)14

Besides the injuries, many in baseball surmised that Messersmith’s dropoff in 1976 was caused by his trying too hard to justify his deal with the Braves. Also, he was worn out by the worry that no team would sign him. And there were hostile fans, some furious at the man they saw as the foremost of “greedy ballplayers,” and Dodgers supporters who felt abandoned by a favorite player for money. He got hate mail, was subjected to obscene insults, was hit by a thrown bottle, and was punched in his pitching arm by a spectator. Some players ripped him in the press. “I’m emotionally drained,” Messersmith conceded. “It goes back to playing without a contract, back to arbitration, to the bidding, to the farce with New York and the Angels, to the demands on my time since (joining the Braves). The whole thing has taken a lot out of me.”15

Messersmith’s second season (1977) with Atlanta was dismal. On July 3, pitching with a 5-4 record and a 4.40 ERA, he tripped and fell on his right elbow while fielding a grounder. He had to have surgery to remove two bone chips. Messersmith did not pitch for the rest of the season. And he never again pitched for Atlanta. Looking to cut down on expenses (Messersmith still had a year on his $1 million contract), Turner sold Messersmith’s contract to the Yankees for $100,000. Since no one knew if Messersmith could return to form, the deal was called “Steinbrenner’s Gamble” in reference to Yankees’ owner George Steinbrenner.

Much to the Yankees’ amazement and pleasure, in spring training of 1978 Messersmith pitched like his former self. Billy Martin, the Yankees’ manager at the time, assigned him to the starting rotation. However, hopes were dashed in an exhibition game when Messersmith fell and suffered a separated shoulder while reaching behind him for an errant throw from the first baseman. Columnist Phil Pepe wrote, “You couldn’t help feeling for the guy. He had come off elbow surgery, battling the odds and the skeptics and even the doctors, but he had come back. He worked harder than the rawest rookie, and he impressed his new teammates with his desire and determination, and he impressed his coaches and manager with his pitching. He had come back, all the way back, and that by itself was a minor miracle, but now … Andy Messersmith cried out of frustration and the next day he said he almost flipped out. ‘That day was the lowest part of my life,’ he said. Of my baseball life,’ he corrected.”16

Messersmith worked hard in rehab and 10 weeks later he was on the mound again. But he really wasn’t ready and finished the season with only 22 1/3 innings of work in five starts with a 0-3 record and a 5.64 ERA. For Steinbrenner the gamble didn’t pay off and in November 1978, Messersmith was released with an invitation to return in spring training to try to make the team.

Messersmith called Peter O’Malley, president of the Dodgers, to inquire about rejoining the club. O’Malley assured Messersmith there were no hard feelings about what had happened three years before. Messersmith impressed the Dodgers in a pitching session, and the Dodgers signed him to a “respectable” two-year contract that included a no-trade clause, the same term that set into motion the whole reserve-clause episode.

But things didn’t go well. Two months into the season Messersmith again had arm trouble (inflammation of a nerve in his pitching arm), which put him on the disabled list for several weeks and eventually the surgery table. His season ended with a 2-4 record in 11 starts in 62 1/3 innings and a 4.91 ERA. In August the Dodgers released him and with that, Andy Messersmith called it a career.

Messersmith moved to Soquel, a beach community about 75 miles south of San Francisco, to enjoy life in the coastal mountains and the surfing. A private, introspective man, he frequently said that when he was done with professional baseball he wanted to live in the mountains and grow his own food.17 Messersmith remarried and had a son. He said that raising his son was the best job he ever had.18

In 1985 and 1986 Messersmith’s name was put forth in the voting for enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame, principally as a symbolic gesture for his pitching prowess and his role in the establishment of free agency. His career won-loss record of 130-99 was not up to Hall of Fame standards, even though his other statistics were as good as or better than those of some starting pitcher contemporaries who made it into the Hall (Steve Carlton, Ferguson Jenkins, Catfish Hunter, Phil Niekro, Jim Palmer, Gaylord Perry, Tom Seaver, and Don Sutton). Among this group, Messersmith had the best hits per nine innings and ERA, the second best won-loss percentage, the third best in shutouts per 40 games, and the third best WHIP. However, Messersmith started only half as many games (290) as his Hall of Fame contemporaries. That they had more impact on the game is the reason they are in the Hall and Messersmith is not. But despite his abbreviated career, Messersmith was clearly a top-notch pitcher, held back in part by the multiplicity of injuries to his throwing hand, elbow, and shoulder.

As difficult as it was for Messersmith to challenge the baseball establishment, he did not regret doing it. “It needed to be done,” he said a decade after his career ended. “I had gone through a couple of negotiations that were very one-sided and it (free agency) became a principle thing to me. The owners kind of had us in a corner. The players need to get some respect.”19

Messersmith had virtually no contact with baseball in the first 10 years of his retirement. Then in 1986 he accepted an offer to coach the baseball team at Cabrillo College, a community college near his home. As he put it, “All of a sudden I’m head baseball coach, head groundskeeper, head nose-wiper.”20 The players referred to him as some face on an antique baseball card.21 About his coaching Messersmith said, “I’m not the world’s greatest coach but I enjoy it. I love the interaction with the kids at that age, making the transition from high school to adulthood. That’s a real special time.”22 Messersmith wasn’t grooming his players to be professional athletes. He was teaching them to see that “if you give 100 percent, no matter what you do, sooner or later you are going to find something in which you will be a success.”23 Messersmith served two stints as baseball coach at Cabrillo, from 1986 to 1991 and from 2005 to 2007, when he retired at age 63.

Messersmith summed up his coaching experience this way: “There’s a major difference between professional and the level I’m coaching. When you work as a professional athlete, you`re very selfish, especially as a pitcher. You don`t worry about anybody else, really. You have tunnel vision. With this, you have to share everything.”24 Messersmith helped students find their way and for him that’s what it all was about: “Knowing I’m serving life. Letting people know I care about them. I try to motivate on love. I don’t think there’s anything else that gets it done like love. I’ve been learning that life serves those who serve it. When I played I was serving only myself.”25

“I loved playing the game,” Messersmith said. “If we could have played it in the backyard I think I would have played every day.”26 As for the business of baseball, he remarked, “In professional baseball there wasn’t any fun. There were too many egos. It was too serious. Guys didn’t have a good time. I believe you can have fun and play … you can have fun and win.”27 “Baseball was always too much work.”28

Messersmith said he hoped to be remembered as a good pitcher, although one who didn’t last too long, and as “a guy who believed in standing up for what he thought was right.”29

Last revised: May 19, 2015

Sources

Books

Bohmer, David. “Marvin Miller and Free Agency: The Pivotal Year, 1969.” In William M. Simons, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2011-2012 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2013), 88-97.

Korr, Charles P. The End of Baseball as We Knew It (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2002).

Lowenfish, Lee. The Imperfect Diamond (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010).

Powers, Albert T. The Business of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2003).

Newspapers and Magazines

Blackman, Frank. “Finally Feeling Like a Million: Free Agent Pioneer Messersmith Doesn’t Miss Majors,” San Francisco Examiner, November 3, 1986.

Durslag, Melvin. “Messersmith Key in Dodgers Deal,” Boston Herald, March 14, 1973.

Foley, Red. “Messersmith Is No Fighter, But He’s a Helluva Pitcher,” New York Daily News, October 12, 1974.

Gustkey, Earl. “Three Years Later, Messersmith Is a Dodger Again,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1979.

Hertzel, Bob. “Sudden Impact,” Pittsburgh Press, December 8, 1985.

Holtzman, Jerome. “Andy M. – Free With No Place to Go,” Syracuse Herald-American, February 22, 1976, 66.

#####_____ “2 Thank You’s for a 6 Million Dollar Man,” Chicago Sun-Times, September 16, 1976.

Hunter, Bob. “Swap to L.A. Gives Andy ‘Good Feeling,’ ” The Sporting News, January 6, 1973: 31.

Macnow, Glen. “Messersmith, McNally: They Had No Idea,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1987

Miller, Dick. “Why Messersmith Is Not in Angels’ Uniform,” The Sporting News, May 8, 1976.

Minshew, Wayne. “Braves Give Hand to Messersmith Pitching in Pain,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1976.

Murray, Jim. “The Baron Loves a Dogfight,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1970.

Newhan, Ross. “Breaks Going for Messersmith,” Los Angeles Times, August 23, 1968.

_____ “Dodgers Closing Ranks After Willie Davis Exit,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1974: 54

_____ “Messersmith Defends Move,” Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1976.

Penner, Mike. “Messersmith Remembered for the Big Curve He Threw Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, February 15, 1988.

Pepe, Phil. “Andy Didn’t Take the Money and Run,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1978.

Verrell, Gordon. “Free Agent Andy Wants to Stay a Dodger.” The Sporting News, January 17, 1976: 35.

_____ “Praise by Peers Spurs Messersmith,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1975.

Weibusch, John. “Angels See a Starter’s Job in Messersmith’s Future.” The Sporting News, September 7, 1968.

_____ “Angel Andy Real Hill Dandy,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1970.

“Messersmith Finds a Home – in Atlanta,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1976: D1.

“Messersmith and McNally: Pioneers Who Fought the System,” Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1981: D4.

“Messersmith Signs with Braves for $1 Million,” St. Petersburg Times, April 11, 1976.

“Messersmith Provides Bonus,” Associated Press, July 3, 1976.

“Messersmith’s Career in Limbo,” Associated Press, March 21, 1976.

Online sources

Abrams, Roger I. “Arbitrator Seitz Sets the Players Free,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2009, sabr.org/research/arbitrator-seitz-sets-players-free, accessed July 19, 2014.

Belth, Alex. “A Fine Mess.” The Bronx Banter Blog, bronxbanterblog.com/2005/12/23/a-fine-mess/, accessed October 2, 2014.

Edmonds, Edmund P. “At the Brink of Free Agency: Creating the Foundation for the Messersmith-McNally Decision – 1968-1975” (2010). Journal Articles. Paper 270.

scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/270, accessed October 17, 2014.

Heuer, Ben. “The Boys of Winter: How Marvin Miller, Andy Messersmith, and Dave McNally Brought Down Baseball’s Historic Reserve System,” law.berkeley.edu/sugarman/Sports_Stories_Messersmith_McNally_Arbitration.pdf, accessed October 18, 2014.

Marshall, Mike. Coaching Pitchers, Chapter 10. drmikemarshall.com/ChapterTen.html, accessed September 5, 2014.

Seimas, Jim. Cabrillo Baseball Coach Andy Messersmith Retires; Replacement Likely Named By Next Week,” mercurynews.com/centralcoast/ci_12525347, acessed July 13, 2014.

Sloope, Terry. “Curt Flood,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/23a120cb, accessed October 1, 2014.

Thornley, Stew. “The Demise of the Reserve Clause,” milkeespress.com/reserveclause.html, accessed October 18, 2014.

Archives

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Andy Messersmith.

University of California, Berkeley Newspaper Archive.

Notes

1 Jim Murray, “The Baron Loves a Dogfight,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1970.

2 John Weibusch, “Angel Andy Real Hill Dandy,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1970.

3 John Weibusch, “Angels See a Starter’s Job in Messersmith’s Future,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1968.

4 John Weibusch, “Angel Andy Real Hill Dandy,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1970.

5 “Messersmith Provides Bonus,” Associated Press, July 3, 1976.

6 Red Foley, “Messersmith Is No Fighter, But He’s a Helluva Pitcher,” New York Daily News, October 12, 1974.

7 Ross Newhan, “Dodgers Closing Ranks After Willie Davis Exit,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1974, 54

8 Gordon Verrell, “Free Agent Andy Wants to Stay a Dodger,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1976.

9 Jerome Holtzman, “Andy M. – Free With No Place To Go,” Syracuse Herald-American, February 22, 1976, 66.

10 “Messersmith and McNally: Pioneers Who Fought the System,” Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1981: D4.

11 David Bohmer, “Marvin Miller and Free Agency: The pivotal year, 1969,” in William M. Simons, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2011-2012 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2013), 88-97.

12 Bob Hertzel, “Sudden Impact,” Pittsburgh Press, December 8, 1985.

13 “Messersmith’s Career in Limbo,” Associated Press, March 21, 1976.

14 Jerome Holtzman, “2 Thank You’s for a 6 Million Dollar Man,” Chicago Sun-Times, September 16, 1976.

15 Ross Newhan, “Messersmith Defends Move,” Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1976.

16 Phil Pepe, “Andy Didn’t Take the Money and Run,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1978.

17 Jerome Holtzman, “Andy M. – Free With No Place To Go,” Syracuse Herald-American, February 22, 1976, 66.

18 Bob Hertzel, “Sudden Impact,” Pittsburgh Press, December 8, 1985.

19 Mike Penner, “Messersmith Remembered for the Big Curve He Threw Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, February 15, 1988.

20 Bob Hertzel, “Sudden Impact” Pittsburgh Press, December 8, 1985.

21 Glen Macnow, “Messersmith, McNally: They Had No Idea,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1987.

22 Mike Penner, “Messersmith Remembered for the Big Curve He Threw Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, February 15, 1988.

23 Bob Hertzel, “Sudden Impact,” Pittsburgh Press, December 8, 1985.

24 Frank Blackman, “Finally Feeling Like a Million: Free Agent Pioneer Messersmith Doesn’t Miss Majors,” San Francisco Examiner, November 3, 1986.

25 Bob Hertzel, “Sudden Impact,” Pittsburgh Press, December 8, 1985.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Frank Blackman, “Finally Feeling Like a Million: Free Agent Pioneer Messersmith Doesn’t Miss Majors,” San Francisco Examiner, November 3, 1986.

29 Glen Macnow, “Messersmith, McNally: They Had No Idea,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1987.

Full Name

John Alexander Messersmith

Born

August 6, 1945 at Toms River, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.