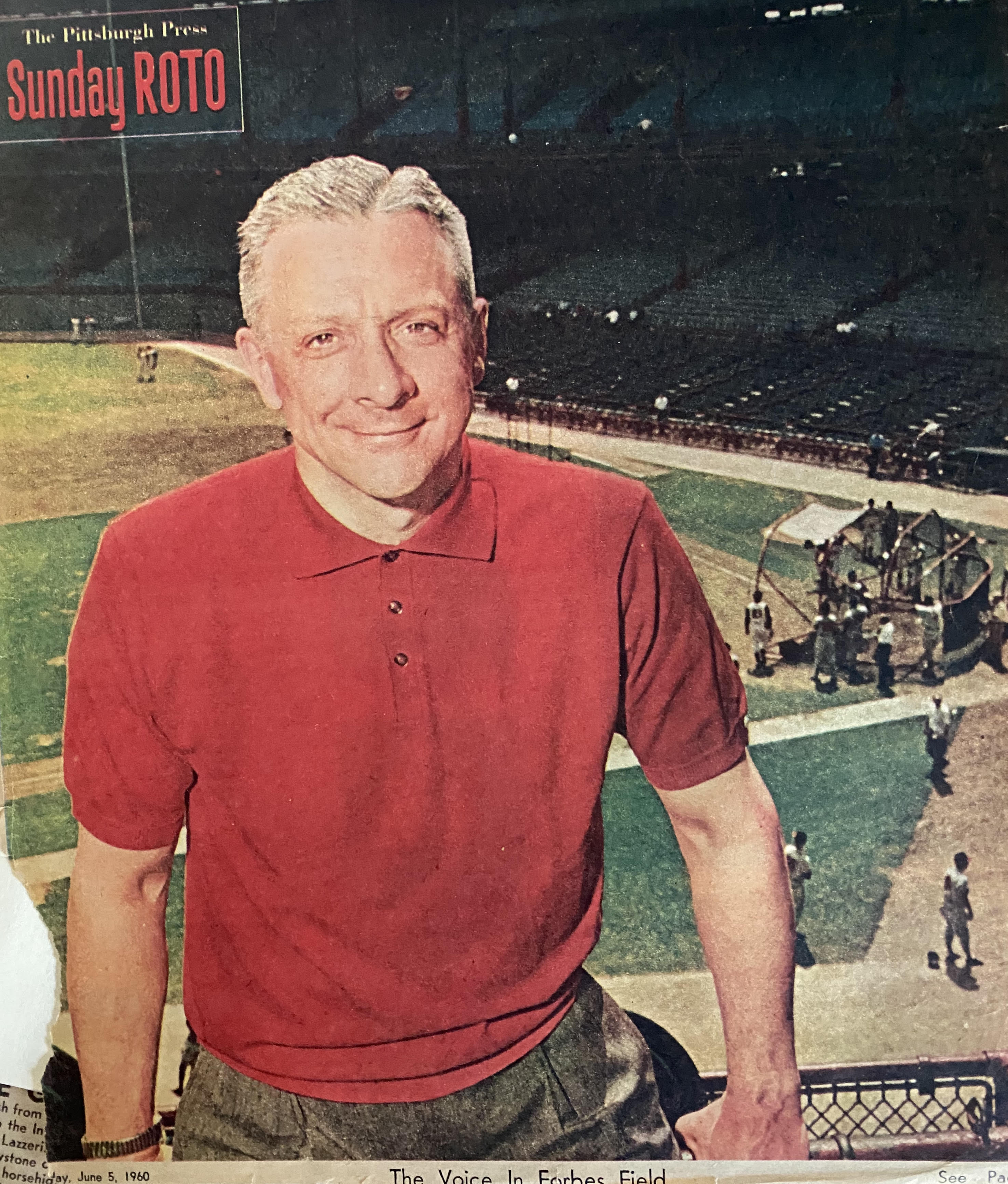

Art McKennan

Baseball parks offer a smorgasbord for the senses. Ask some longtime Pittsburghers to describe Forbes Field and you will find yourself awash in sensory detail, little things that made the place vivid and unforgettable. Those older Pirate fans may recall the lush, green ivy that cloaked the outfield wall. They may recall the bracing, manly odor of old beer and cigarettes, which hung in the air like a permanent cloud and mingled with the tantalizing scent of red hots and roasted peanuts. And they may recall the voice of Art McKennan, the Pirates’ longtime public address announcer, whose warm baritone sounded like a sunny Sunday afternoon.

Baseball parks offer a smorgasbord for the senses. Ask some longtime Pittsburghers to describe Forbes Field and you will find yourself awash in sensory detail, little things that made the place vivid and unforgettable. Those older Pirate fans may recall the lush, green ivy that cloaked the outfield wall. They may recall the bracing, manly odor of old beer and cigarettes, which hung in the air like a permanent cloud and mingled with the tantalizing scent of red hots and roasted peanuts. And they may recall the voice of Art McKennan, the Pirates’ longtime public address announcer, whose warm baritone sounded like a sunny Sunday afternoon.

Arthur R. McKennan, born on November 11, 1906, grew up in the shadow of Forbes Field in the Oakland section of the city. He might have inherited his sonorous voice from his mother, Leora, a professional singer who performed with the Pittsburgh Symphony. His father, Moore McKennan, was a company doctor with Jones and Laughlin Steel for more than 30 years, and at one time Art assumed medicine was his calling, too. After all, his grandfather and two uncles were also practicing physicians, so it was kind of the family business. His father’s friends even took to calling Art “Little Doc.”

Moore was crazy about the Pirates and organized his schedule so he could attend as many games as possible. He began taking Art with him when he turned nine, and his son quickly caught the bug. Soon, Art wanted to be at Forbes Field all the time. Reluctant to beg his father for money, he began hanging around the players’ entrance in the summer of 1919, hoping to finagle his way into the ballpark somehow. Outfielder Billy Southworth noticed him and thought he might make a good errand boy.

For the next few weeks, McKennan arrived at the park at eleven each morning, settled in atop an equipment trunk outside the clubhouse, and waited for someone to ask him to do something. Typically, the equipment manager would dispatch him to pick up some sandwiches or send him off with clothes to be pressed or gloves to be repaired.

His conscientiousness earned him a promotion of sorts. “I was made a foul tip boy,” McKennan remembered. “That’s a strange term, but there were 100 feet in back of the catcher at Forbes Field. They had to have someone sit back there and throw the balls back because it was too far for the catcher to go and get them, and the batboy was always on the bench.”

In 1920, McKennan advanced to batboy. It was thrilling for him, being down on the field, right in the middle of the action; the problem was the job didn’t pay. So in the middle of the 1922 season he jumped at the opportunity to make some money–a dollar a game to operate Forbes Field’s manual scoreboard. It was a hard-earned buck. “The inside of that scoreboard was the hottest thing on God’s earth,” he declared. “We ran around inside in our shorts, and you had to take these big sheet steel plates and slide them into racks.”

Three-quarters of a century later, McKennan still could paint a vivid picture of those nearly-forgotten Pirate teams. He told of third baseman Possum Whitted keeping bird dogs in a kennel by the clubhouse, and fellow infielder Cotton Tierney practicing his golf game in the outfield grass. He described what it was like to watch legendary outfielder Max Carey. “He ran as if he were on springs. He walked that way, too.” He recalled his curiosity upon seeing the great third baseman Pie Traynor amble into the clubhouse for the first time. “He was the rawest-looking thing you ever saw in your life– knock-kneed and big, wide shoulders.”

McKennan realized he was living the dream of any baseball-loving teenager; suddenly, a medical career didn’t seem so enticing. “Once I got around all those big, strong guys, I said to myself, this is what I want to do with my life.” After high school, however, McKennan had to set those ambitions aside temporarily and figure out a way to pay the bills. He toiled briefly for a local pharmaceutical manufacturer, and then as a messenger for a downtown brokerage, all the while working as an usher at the ballpark whenever he had time.

In September 1930, McKennan was playing golf when he noticed a strange weak feeling in his legs. “I left after nine holes. The next day I went back to the [brokerage] and I noticed, going down the front steps, that my back was extremely stiff.” He tried to usher at a Duquesne University football game but the discomfort just got worse. His older brother had to come by to drive him home. “That was the end,” he said grimly. It was polio. He would never walk again. “There were tears on the inside,” he confessed. “I was used to playing ball and dancing. Now I’d have to learn to be a watcher.”

McKennan spent the next 11 years engaged in a long, torturous struggle for recovery. At first, everything below his waist was useless; he couldn’t even control his bowels or his bladder. His mother was his physical therapist, dutifully administering grueling two-hour treatments twice each day. In 1931, at the suggestion of his doctors, he took up swimming. Charles Hyatt, an aquatics instructor at the Pittsburgh Athletic Association, literally carried McKennan on his back and into the water for two years until he could manage to climb into the pool himself. Eventually, he regained enough strength to live independently and work. “I could talk from now until Christmas and still not adequately express my thanks or tell of the good things that many people did for me,” he marveled in a June 1960 interview.

Although his life had been dramatically altered, his enthusiasm for the Pirates remained undiminished. Then before the 1948 season, a routine telephone conversation sent his life in a new direction. McKennan, who returned to the Bucs in 1942 to operate a new electronic scoreboard, was on the line with Al Schlensker, the club’s new man in charge of operations. Schlensker was so taken by the deep, commanding tone of McKennan’s voice that he offered to make him the team’s new public address announcer.

That was just about the last thing McKennan expected to hear. No one had ever complimented his voice before, and he had never, not even for a second, retained any desire to sit behind a microphone. But although he needed some convincing, McKennan eventually agreed to take the job.

The public address system was a recent innovation at Forbes Field. Originally, the home plate umpire simply walked toward the backstop and barked out the starting lineups. If you weren’t seated close by, you were pretty much in the dark. In the 1920s and ‘30s, the Pirates employed a man to march from third base, to home plate, and then to first base, shouting announcements through a megaphone. Something resembling a modern system came in along with the new scoreboard in 1940. The announcer initially stationed himself in the first row of the stands, his microphone perched on the dugout roof. When McKennan took over, he worked from above home plate, inside a tiny booth with low-hanging steel girders that he said reminded him of a birdcage.

Neither McKennan nor anyone else in the organization knew much about public address announcing. Early on he relied heavily on feedback from local radio personality Ray Scott, who later gained renown for his stripped-down, “just-the-facts-ma’am” delivery on NFL football telecasts. McKennan’s approach was similar. “I was low-key and tried to say as little as possible,” he explained. “The more you say, the less they’re going to listen.”

His voice was, in the words of an Associated Press reporter, “as distinct and lively as the tones of a Stradivarius.” He wasn’t a screamer or a cheerleader. Rather, he spoke with a relaxed formality and dignity, almost if he were welcoming a new friend into his home. “The whole appeal of his style was that he never talked ‘at’ people. He talked to them,” according to Tim DeBacco, who assumed public address duties for the Pirates in 1988. “He had such a folksy, friendly, conversational style. He was never addressing a crowd. It was almost as if he could be talking to every person in a room.”

McKennan abided by what he called the three C’s of announcing–being clear, concise, and correct. “I’m a typical Scorpio,” he joked. “I’m a nitpicker.” He practiced his diction at home by reading aloud from books and magazines and became a stickler for proper pronunciation. (For example, the St. Louis team was always the “Card-in-als,” never the “Card-nals”). Multi-syllabic names that danced off the tongue gave him a visceral joy. (“Rafael Belliard. I loved to say that name.”)

That’s not to say he was perfect. Once when promoting an upcoming home stand, he informed the crowd, “Tickets are on dale saily.” During a game against St. Louis, he blundered, “The Phillies and Cardinals thank you for attending.” Then there was a notorious senior moment in the 1980s when he confused Marvell Wynne, a lithe African-American outfielder, with Pirate teammate Jim Winn, a thickset Caucasian relief pitcher. He announced, “Now batting…Jim Winn.” As the opposing pitcher went into his windup, McKennan’s voice suddenly blared from the speakers again. “Correction, that’s Marvell Wynne…Sorry, Marvell.”

McKennan balanced several different responsibilities during a game. For many years, he ran the scoreboard while doing the announcing, a feat that required a high level of concentration. “You have to keep your wits about you,” he said. He earned a reputation for the fastest fingers in the league, consistently posting “ball” or “strike” before most fans had a chance to look up.

McKennan balanced several different responsibilities during a game. For many years, he ran the scoreboard while doing the announcing, a feat that required a high level of concentration. “You have to keep your wits about you,” he said. He earned a reputation for the fastest fingers in the league, consistently posting “ball” or “strike” before most fans had a chance to look up.

At Forbes Field, McKennan also directed the in-game entertainment, such as it was before the advent of mascot races and T-shirt tosses. “There wasn’t much flubdubber,” McKennan said. “You just got a ballgame. If you didn’t like it, you could stay home.” His musical playlist included an eclectic mix of show tunes, marches, and even a little Dixieland. If the Pirates were winning at the 7th-inning stretch, he threw on the traditional “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” If they were losing or tied it was “With a Little Bit of Luck” from My Fair Lady. Sportswriter Ken Smith once remarked, “This is the only ballpark in which I ever heard Chopin,” an observation that delighted McKennan to no end.

Other than a 30-game stretch in 1951 when he was recuperating from a broken leg, McKennan was behind the microphone for every home game from 1948 until the Pirates departed Forbes Field. His voice became part of the place; one of his most treasured mementos was an autographed baseball on which Roberto Clemente thanked him for all his work there. The final game at Forbes, on June 28, 1970, was painful for him. After the final out was recorded, fans went on a souvenir-gathering rampage, tearing up grass, dislodging bases, yanking out seats, even stealing the numbers off the scoreboard. A livid McKennan began scolding the crowd, “Please leave immediately! There is a danger of electrocution and I mean it!” He even resorted to playing the national anthem in a futile attempt to stop the destruction. “Look,” he growled to a reporter in disgust, “The most beautiful park in the country and they have to do this.”

McKennan was a sweetheart–thoughtful and avuncular with a droll sense of humor and a fondness for limericks. But he also was a deeply passionate Pirates fan, and, although he never betrayed his emotions on the microphone, a tough loss could transform him into a raging, red-faced, crutch-throwing demon. Greg Brown, who worked in the scoreboard room with McKennan at Three Rivers Stadium, never saw anything like it. “Managers are bad after a loss, but no one was as bad as Art McKennan.” Pirate vice-president Joe O’Toole once hosted some guests from Japan. One minute they’re watching the game in peace; the next minute they’re being bombarded by the unnerving sound of a little old man going completely berserk. “After the game, O’Toole came up to me and said I scared the Japanese,” McKennan laughed. “He was afraid I was going to start an international incident.” One particularly violent eruption prompted his friends on the scoreboard crew to report for work the next day sporting batting helmets.

Despite his disability, McKennan led a busy, sometimes even hectic life. He worked for Pittsburgh’s Parks and Recreation Department for 30 years, rising from an entry-level clerk to superintendent of administration. In that position, he organized the city’s youth baseball, basketball, and softball leagues. After retiring in 1972, he volunteered with the Shadyside Boys Club, helping to run its summer programs. McKennan also was a staple on the local sports scene. He did public address for Duquesne basketball for nearly two decades, operated the scoreboard at Steelers football games for 16 years, spent a couple of seasons in the late 1960s announcing for the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins, and throughout the 1970s was the internal public address voice of University of Pittsburgh football, where he provided details of the action for members of the media and fans in the VIP boxes.

McKennan worked both the scoreboard and public address for two All-Star Games and three World Series. “I was [more] proud of that than anything,” he proclaimed. But as he aged, the work began taking a toll. “My hip really stiffens up,” he told the Pittsburgh Press in 1985. “When I got out of here the other night at two a.m. after a two-hour rain delay, I was a basket case.” Greg Brown, who worked in the booth near McKennan, remembers seeing him in agony many times. “On occasion he would try to stand for the seventh-inning stretch, just to get a stretch, and you could see the pain on his face. It was really, really tough on him.”

In 1987, the Pirates decided to move in a different direction. Some months earlier they hired Bernie Mullin, a sports management professor from the University of Massachusetts, to create a more compelling game experience. “Bernie was British. He didn’t have a background in baseball. He didn’t know Pittsburgh either,” contended John Mehno, a Pittsburgh newspaper reporter. One of Mullin’s first decisions was to strip McKennan of his announcing responsibilities. “We felt we needed a voice with more enthusiasm,” he informed reporters. “We’re looking at the stadium-theater concept, tying together the scoreboard, the [mascot], and the announcer. All that integration requires someone to work spontaneously.”

So the Pirates entered their 100th anniversary season without their longtime voice. “He was really upset about it,” recalled Greg Brown. “He tried to put the best face on it he could publicly, but it really hurt him.” While McKennan was stung, fans and the media were furious. The outcry was so intense that the Pirates relented and brought him back to work Sunday games, which he continued until April 1993. His colleague June Schaut said he retired only after the job had become almost physically impossible. “He had difficulties even getting into or out of his chair [from his wheelchair]. But he didn’t want to give it up. It was his life.”

McKennan was 89 when he died at Allegheny General Hospital on April 23, 1996. He never married; his only surviving relative was a nephew who lived in suburban Pittsburgh. “The amount of trouble I was, I don’t see how I could take a wife,” McKennan lamented. “I told myself, ‘Buddy, you’re a bachelor.’ It just wasn’t in the cards.” It seemed that his real love affair was with the Pittsburgh Pirates and that seat behind the microphone. “You don’t quit a job like this,” he once swore. “I’m happier here than I could be anywhere.”

Sources

John McCollister, The Bucs: The Story of the Pittsburgh Pirates (Lenexa, KS: Addax Publishing Group, 1998), 176.

Indiana (PA) Evening Gazette, August 9, 1980; April 12, 1993.

Los Angeles Times, July 9, 1976.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 17, 1974; March 18, 1987; April 24, 1996.

Pittsburgh Press, June 4, 1960; June 3, 1985; April 11, 1987.

Wisconsin State Journal, June 30, 1970.

Tim DeBacco videotape, oral history interview with Art McKennan, c. 1993.

“SABR Oral History Project: Interview with Art McKennan,” by Rod Roberts, July 14, 1994.

Greg Brown, telephone interview with author, November 17, 2011.

Marty Corbett, telephone interview with author, December 8, 2011.

Tim DeBacco, telephone interview with author, November 22, 2011.

John Mehno, telephone interview with author, November 21, 2011.

June Schaut, telephone interview with author, December 1, 2011.

Full Name

Arthur R. McKennan

Born

November 11, 1906 at Pittsburgh, PA (US)

Died

April 23, 1996 at Pittsburgh, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.