Jim Brosnan

A fine major league pitcher for several years, Jim Brosnan wrote the first honest portrayal of the life of a baseball player. The Long Season and subsequent works have earned him continued praise ever since. His writings paved the way for many other players’ “autobiographies,” usually written with considerable help, and filled with more tawdriness but less humor and heart. Fifty years on, Brosnan’s books remain the gold standard for baseball memoirs.

A fine major league pitcher for several years, Jim Brosnan wrote the first honest portrayal of the life of a baseball player. The Long Season and subsequent works have earned him continued praise ever since. His writings paved the way for many other players’ “autobiographies,” usually written with considerable help, and filled with more tawdriness but less humor and heart. Fifty years on, Brosnan’s books remain the gold standard for baseball memoirs.

James Patrick Brosnan began life in Cincinnati, Ohio, on October 24, 1929, one of five children born to John and Rose Brosnan. John worked for the Cincinnati Milling Company as a lathe operator, while Rose was a piano teacher and a nurse. The couple was responsible for instilling very different interests in the family. “My mother exposed the children to music,” Brosnan later recalled. “My father was completely baseball minded. When I was six or seven, I’d go to the library every week to pick out books for my mother to read to me. My father would throw sports books at me and say, ‘Don’t read that junk—read this.’”1

Brosnan’s intelligence and thirst for knowledge was evident early. Musically, he started off playing the trombone, but switched to the piano and learned to play complicated classical pieces. He skipped first grade, and later took seven years of Latin. “I had eclectic tastes,” he recalled. “I particularly enjoyed reading Joseph Altschuler, a children’s historian who wrote several novels about American Indians… My ambitions as a kid were to write a book or be a doctor, something like that, and way off in the distance, maybe be a major league baseball player.”2

Membership in the Knothole Gang in Cincinnati allowed him to watch many Reds games at Crosley Field, and he played a lot of baseball. Brosnan was a tall (6’1”), skinny kid in high school, too thin for football but strong enough to pitch. He played just one year of high school baseball, but played for the Bentley Post American Legion team that made the national finals in 1946. Well aided by teammates Don Zimmer and Jim Frey, Brosnan chipped in with two shutouts in the regional and sectional finals, one a two-hitter and the other a three-hitter. There were plenty of big league scouts at the tourney, and in November 1946 Brosnan signed with Tony Lucadello and the Chicago Cubs for $2,500. The 17-year-old had finished high school the previous June.

In 1947 Brosnan traveled to Shelby, North Carolina, where the Cubs minor league teams were training. Jack Sheehan, who ran the Cubs farm system, was impressed but wary. “The guy had good poise, real good stuff for a youngster and good speed. He had an exceptional curve ball for a boy that age. He was impetuous though; he wanted to learn everything he could right away. He was a fellow who wasn’t easy to get acquainted with.”3 The 17-year-old began his career with Elizabethton TN of the Class D Appalachian League, and finished 17-8 with a 3.04 ERA. A great start.

His next season was filled with poor pitching and a general lack of decorum. After one drubbing while pitching for Fayetteville NC, Brosnan left the mound and the clubhouse, packed his bags, and returned home to Cincinnati. He eventually rejoined the team, but things did not improve; he finished 7-13 on the season, split between two clubs.

Cubs general manager Jim Gallagher related the young hurler’s story to Arthur Meyerhoff, a team stockholder and the head of a Chicago ad agency. Meyerhoff asked to meet Brosnan, and the two became friends. Meyerhoff recommended he seek counseling, which Brosnan did for two years. “Analysis, my marriage, and knowing Meyerhoff were the most important steps in my social readjustment,” recalled Brosnan. “Meyerhoff took a very fatherly interest in me.” Meyerhoff remembered, “He was surly and antagonistic, but he was a brilliant guy. He was so sensitive.”4

Brosnan was not out of the woods yet. After a decent year for single-A Macon in 1949 (9-11, 3.77), he took another step backward in 1950. He played for four different teams, finishing 7-10 with a ghastly 6.21 ERA. Morrie Arnovich, his manager in Decatur, filed the following report to the Cubs: “Reported unhappy, still lone wolf. Started off not reporting on time and leaving park after being taken out of game, but doing little more. … The last time he pitched he walked to the plate in batting practice without a cap and, when not at the plate, sat on the bench reading a magazine. Was told about these things.”5 After the season, he spent two years in the U.S. Army.

He dreaded the army, but it turned out much better than he had feared. Brosnan did not die in Korea, as he had expected, instead spending his entire hitch at Fort Meade in Maryland, winning 50 games for the post team. Even better, he met Anne Stewart Pitcher, a Virginian who worked on the post. “I was very much interested in music,” recalled Anne Stewart. “All the people I knew there weren’t. Some pretended to be, but they weren’t really. The night I met Jim he talked about Bartok and Virgil Thomson’s tone poem, and I said to myself, ‘Here’s another one who’s pretending that he likes music.’ When I saw my roommate later I said to her, ‘That was a very interesting man. I wonder if he really likes music.’”6

While at Fort Meade Brosnan regularly took a bus to Washington to see the National Symphony Orchestra perform. Anne Stewart began driving him to the concerts: “The only reason we got together, we both like music and I had a car.” Six months after meeting, on June 23, 1952, the two were married. Soon there were three children: Jamie, Tim, and Kimberlee. They settled in the Chicago area, buying a house in suburban Morton Grove.

Brosnan’s first year back in Organized Baseball the next year was less than triumphant, as he finished 4-17 for Triple-A Springfield, in the International League. He had taken an aptitude test in the army and had learned he was most suited to be a writer or an accountant. Seeing his baseball career going nowhere and needing to make some money to support a growing family, he enrolled in an accounting course at Benjamin Franklin College in Washington DC. To his surprise, he was invited to spring training with the Cubs in 1954, and, even more surprisingly, he made the team. “I wasn’t ready,” recalled Brosnan. “I couldn’t pitch in the big leagues; I didn’t know how. And they soon found out.”7 The 24-year-old pitched 18 games with a 9.45 ERA before he was sent down to Beaumont in the Texas League.

With Beaumont he began throwing the slider, which would become his best pitch. He finished 7-1 in Texas, and won 17 games the next season for Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League. He still had no close friends. At home he had a wife and a new baby, and on the road he went to art museums or sat in his room reading Stendhal and Dostoevsky. “If I went to a foreign movie, I went by myself.”8

One day in Oakland he lost a tough game in extra innings, and was distraught enough that he went out drinking with his brother, who was living in San Francisco. The two were soon quite drunk, and ran into some of Jim’s teammates, who had never seen him in such a state. Naturally, they bought him more drinks, and had to help him into the taxi to get to the airport. There, they ran into more teammates who insisted they should get in on the fun. When Brosnan got off the plane in Los Angeles, Anne Stewart saw her husband’s condition and walked away. But the binge made him a full member of the team.

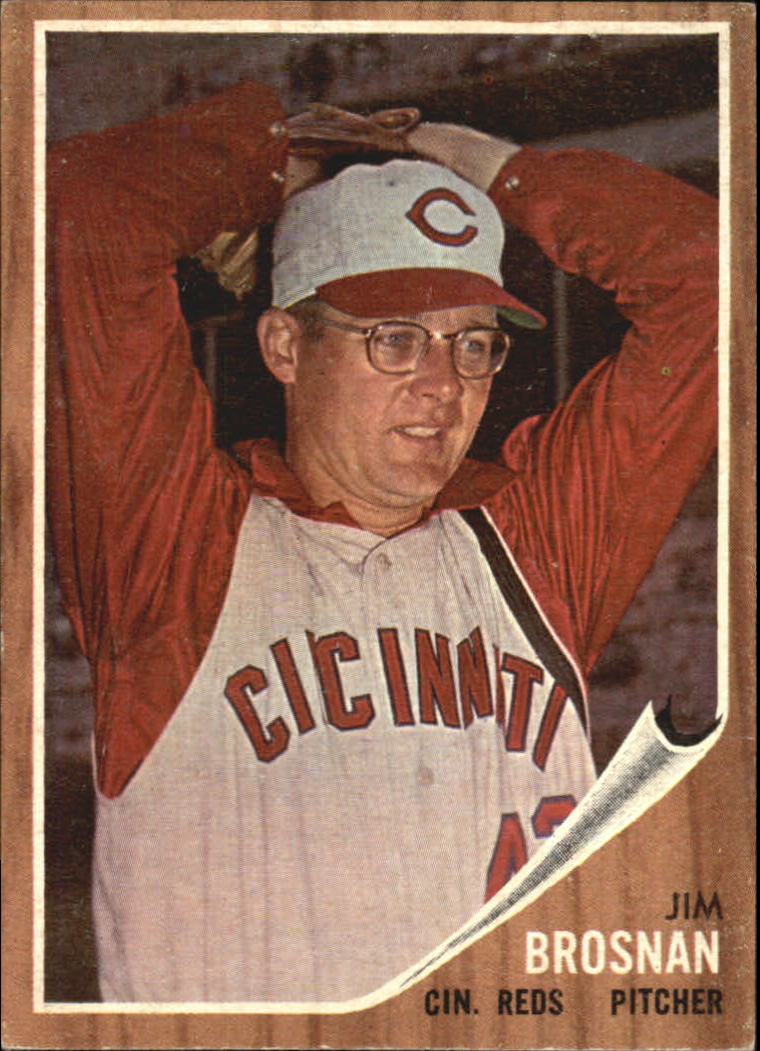

He stuck with the Cubs again in 1956, and this time he was ready. The tall, skinny high school kid was now 6’4” and 210 pounds, with blond hair and blue eyes behind his horn-rimmed glasses. Working as a starter and out of the bullpen, Brosnan finished 5-9 with a 3.79 ERA for a poor Chicago team. The next season, in a similar role, he put up a 5-5 record and led the club with a 3.38 ERA in 99 innings.

Years later, Brosnan asked Don Osborn, who had been his manager at two minor league stops, why he had stuck with him for so long despite years of disappointment. Osborn told him the Cubs knew he had a great arm, but were less sure of his head and his heart. “He was right,” Brosnan admitted. “I wasn’t driven to be a professional baseball player. By 1958 I began to hate to lose at pitching; I hated it even when somebody got a hit off me. The competitive urge finally came to me, but when it came I was already in the big leagues.”9

Still, Brosnan’s intellect and eccentricities stood out in the world of baseball. He read constantly, carrying a small library of books with him on the road, watched foreign movies, smoked a pipe, and used a baffling vocabulary. One time on the mound, he imperiously yelled at a confused batter, “Ils ne passeront pas!” 10 (The phrase, whose English translation is “They shall not pass,” had earned fame as the rallying cry for the French at the Battle of Verdun in the first World War.) A few years later Frank Robinson gave him his enduring, though not surprising, nickname: “Professor.”

Brosnan was the Cubs’ Opening Day starter in 1958, pitching six shutout innings in a victory over the Cardinals. He pitched well early in the season, putting up a 3.14 ERA in eight starts, before being traded to St. Louis on May 20 for infielder Alvin Dark. Brosnan returned to a swingman role with the Cardinals, but had a fine season overall—11-8 with a 3.35 ERA, the seventh lowest figure in the league.

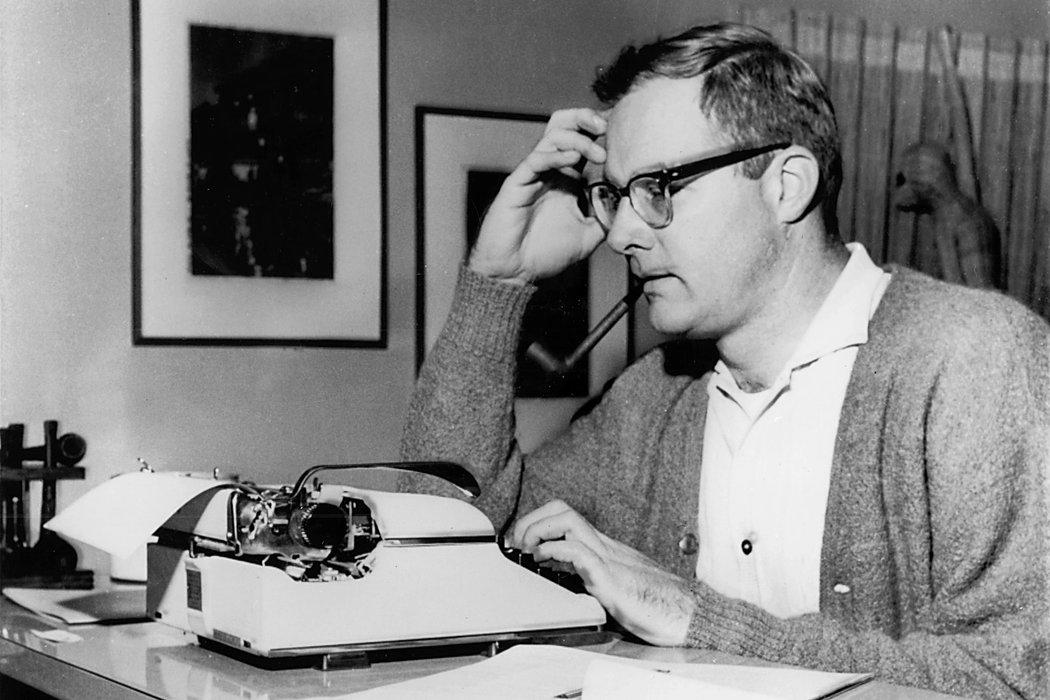

Around this time he began his writing career. He had become friendly with a writer for Sports Illustrated, who suggested that Brosnan should write about baseball. Brosnan had been keeping a diary off and on for years, but did not feel he’d done anything interesting yet. After his trade to the Cardinals, he sent Sports Illustrated an excerpt from his diary, and it ran in the July 21, 1958, issue. Brosnan’s intellect and writing ability were a revelation at a time when readers had been served vanilla depictions of their baseball heroes performing glorious deeds on the fields of battle. Brosnan drew himself and his teammates as complicated humans struggling to make their way.

After his sudden change of employers, he wrote of the charade of the player-management relationship. “[General manager John] Holland’s words,” Brosnan wrote, “‘I don’t know whether this is good news or bad news’… and ‘We appreciate all you’ve done for the organization,’ while probably well intentioned, were spoken like a poor actor at first rehearsal. The self-hypnosis about the Grand Nature of the Good American Game tends to delude the managers of baseball.” More practically, he had to tell his wife he was no longer playing for the team near their home. “My wife cried via long distance from Chicago… for ten minutes. I did, too … a little. Why me?”11

His article received positive reviews, and he soon had an agreement with Harper & Brothers Publishers to write a book in the same diary format, covering the upcoming 1959 season. Brosnan began keeping notes whenever something interested him. These events were just as likely to happen in the bullpen, or airport, or hotel, as they were during a ballgame. The Cardinals gave the story a dramatic twist when they traded him in June to the Cincinnati Reds for pitcher Hal Jeffcoat. Thus his journal could again directly address his feelings about the life of an itinerant ballplayer. For the season Brosnan finished 9-6 with a 3.79 ERA, and spent the summer tapping away on his typewriter.

An excerpt from The Long Season, about his positive relationship with Reds’ manager Fred Hutchinson, was published in Sports Illustrated in the spring of 1960, and the book was released in hardcover in July. It received wonderful reviews in the press, including in Time (“a deft wry account of his struggles as a pitcher last year”), the New York Times (“a fascinating and embittered view of what our capitalistic national game has to offer to the average ballplayer”), and the Los Angeles Times (“a rich and always interesting account of the great game as seen through the eyes of an articulate ballplayer”).12 The great sportswriter Red Smith called it “a cocky book, caustic and candid and, in a way, courageous, for Brosnan calls him like he sees them, doesn’t hesitate to name names, and employs ridicule like a stiletto.”13 Jimmy Cannon, another famed sportswriter, simply called it “the greatest baseball book ever written.”14

Brosnan broke new ground by letting the reader experience the day-to-day existence of the major league player. Many of these days were fun, and many were boring (though Brosnan’s humor keeps the reader interested). The young men took a liking to young women (though Brosnan did not go into detail) and to alcohol. In the very first paragraph of the book, Brosnan writes, “I had called home to see if there were enough olives for the martini hour.”15 Some baseball people were less than amused (Joe Garagiola called Brosnan “a kookie beatnik”), most particularly because he painted a less than flattering portrait of baseball management. His treatment of Solly Hemus, his manager with the Cardinals, was harsh. “You think Brosnan’s writing is funny,” said Hemus, “wait until you see him pitch.”16

Brosnan was at his best when writing of the difficulties faced by players, particularly when they are traded without warning, as he was. “Oh, God, Meat, not that,” his wife cried. “I’ll never be able to drive from Chicago to Cincinnati.” And: “Jeffcoat! Couldn’t they get more than that? Oh, honey, they just wanted to get rid of you.” Brosnan himself had changed in the previous year. “I sat back on the couch, half-breathing as I waited for indignation to flush good red blood to my head. Nothing happened. I took a deep breath, then exhaled slowly. It’s true. The second time you’re sold you don’t feel a thing.”17

Despite the criticism Brosnan endured for revealing too much about the lives of players, he believed that later books, such as Jim Bouton’s Ball Four, did go too far in their language and revelations of sexual behavior. But Brosnan felt that baseball had been done a disservice when earlier writers had whitewashed it. “The life we led had not been truly represented in print,” he recalled. “Even the good writers had held off from writing the truth in order to preserve their relationship with the ballclubs.”18 As Brosnan did not discuss the personal lives of individual players, he was not ostracized even by the teammates who criticized the book.

Through it all, he continued to pitch well. In 1960 he appeared in 57 games, and finished 7-2 with a career-low 2.36 ERA and 12 saves that were fourth most in the National League. “Broz had the stuff and control,” said manager Hutchinson, “and became more confident as he went along.”19 His most rewarding season came in 1961, when, for the first and only time, he pitched in a pennant race. Brosnan was a key member of the staff (10-4, 3.04, 16 saves), as Cincinnati prevailed to win a surprising pennant, their first in 21 years. Brosnan pitched three times in the World Series, twice in scoreless outings but getting hit hard in Game 4. The heavily favored New York Yankees took the series in five games.

Two weeks later, Brosnan’s story about the World Series—wryly titled “Embarrassing, Wasn’t It?”—appeared in Sports Illustrated. “There are three monuments in center field,” he wrote of his first look at Yankee Stadium, “and plenty of room for more future self-exaltation if such is necessary to prove the greater glory of the Yankees.” But Brosnan had wanted to win, and wrote honestly about his team’s failure to do so.20

The following spring Harper published Brosnan’s second book, Pennant Race, a journal of the 1961 season. The book abruptly ends with the regular season, likely because Sports Illustrated had already run the World Series material. Praise again was the order of the day, and Brosnan always believed that his writing improved in his second effort. “To get to [Cincinnati’s] Crosley Field,” he wrote, “I usually take a bus through the old crumbling streets of the Bottoms. Negroes stand on the corners watching their homes fall down. The insecurity of being in the second division of the National League leaves me. For 25 cents, the daily bus ride gives me enough humility to get me through any baseball game, or season.”21

By this time Brosnan had become a prolific freelance baseball writer, his work appearing in The Atlantic, Esquire, Look, Life, Sports Illustrated, Sport and Saturday Evening Post, among others. He wrote in the first person, but about general topics such as spring training, the spitball, or Little League parents. He wrote mainly in the off-season, although the stories were often published during the season. This last would prove to be a problem.

The Reds won 98 games in 1962, not enough to keep up with either the Giants or Dodgers. The 32-year-old Brosnan had another fine year in the bullpen (4-4 with 13 saves). Nonetheless, very early the next season he was traded to the Chicago White Sox, because, according to Brosnan, the Reds wanted to shed his $30,000 salary, which was one of the highest on the team.

When Brosnan arrived in Chicago, general manager Ed Short greeted him by telling him he would not be able to write or publish anything during the baseball season. Brosnan reluctantly went along, at least for a while. The White Sox already had Hoyt Wilhelm and Eddie Fisher in the bullpen, but Brosnan got plenty of important work. He recorded saves in his first four outings, and finished with a deceptive 3-8 record, a 2.84 ERA and 14 saves. The White Sox finished a strong second to the Yankees, and their excellent bullpen was one of the primary reasons.

After the 1963 season Brosnan received a contract calling for a pay cut and a continued ban on writing. The pitcher-author balked, reasoning that, at the very least, he needed to write to make up for the lesser salary. Moreover, he had already sold two stories that would be coming out in the early part of the season. The White Sox released him before spring training, and no other major league team was interested in the services of one of the best relief pitchers in the game. The Sporting News and Sports Illustrated rallied to his side, but his playing career was over at the age of 34. “Quitting didn’t bother me,” Brosnan later remembered. “I was a writer, I was going to be a writer.”22

While continuing to write regular baseball articles, Brosnan also worked for an ad agency, as he had during the off-seasons for many years, and in broadcasting. He published several baseball books for young readers (titles like Great Baseball Pitchers and The Ted Simmons Story). In the early 1970s he began writing baseball articles for Boys’ Life, which he continued to do for 20 years. By 2011 he had been fully retired for many years, still happily married to Anne Stewart and still living in the house in Morton Grove they had bought 55 years earlier.

Brosnan often referred to himself as an “average major league player,” a depiction that is inaccurate. His was a good pitcher for many years, and one of the best relievers in the game in the early 1960s. But his legacy will remain his writing, especially his two classic books. He paved the way for many future memoirs, but only Brosnan wrote his books without help. His stature as the best writer ever to emerge from the baseball playing ranks is still safe after fifty years. “My kids will resent me saying this,” he later said, “but when Long Season came out I felt as proud as a father.”23

Brosnan died on June 28, 2014.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Warren Corbett for his editorial assistance.

Notes

1 Al Silverman, “Major-League Intellectual,” Saturday Evening Post, May 13, 1961.

2 Mike Shannon, Baseball—The Writer’s Game (Diamond Communications, 1992), 18.

3 Silverman, “Major-League Intellectual.”

4 Silverman, “Major-League Intellectual.”

5 Silverman, “Major-League Intellectual.”

6 Silverman, “Major-League Intellectual.”

7 Shannon, Baseball—The Writer’s Game, 19.

8 Silverman, “Major-League Intellectual.”

9 Shannon, Baseball—The Writer’s Game, 20.

10 “Lowbrow Highbrow,” Time, September 5, 1960.

11 Jim Brosnan, “Now Pitching for St. Louis: … the Rookie Psychiatrist,” Sports Illustrated, July 21, 1958.

12 “Lowbrow Highbrow”; “Books of the Times,” New York Times, July 6, 1960, 31; Robert Kirsch, “An Articulate Baseball Player,” Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1960, B5.

13 Dave Hoekstra, “Brosnan’s books cover all the bases,” Chicago Sun-Times, August 8, 2004.

16 Mark Armour, “Ball Four,” Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/ball-four

17 Brosnan, The Long Season, 160.

18 Dick Johnson, interview with Brosnan, SABR Review of Books Vol. 5 (SABR, 1990).

19 Silverman, “Major-League Intellectual.”

20 Jim Brosnan, “Embarassing, Wasn’t It?” Sports Illustrated, October 23, 1961.

Full Name

James Patrick Brosnan

Born

October 24, 1929 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

June 28, 2014 at Park Ridge, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.