Author Wiggen Goes East: Jim Brosnan and the 1958 Cardinals Tour of Japan

This article was written by Adam Berenbak

This article was published in Spring 2018 Baseball Research Journal

October 16, 1958

Robert Hyland, General Manager, KMOX Radio

In my opinion, there is no more effective way of strengthening mutual understanding among nations than through the people to people approach, and I am convinced that international sports engagements are playing a very important role in building international friendship and good will. For that reason, I particularly appreciate this opportunity to congratulate KMOX Radio and all those responsible for broadcasting the games which the St. Louis Cardinals will be playing in Japan. Because of your efforts a maximum number of both Japanese and Americans will be able to communicate with each other through the common medium of baseball, and thereby promote the spirit of sportsmanship and international understanding. It gives me great pleasure to join baseball fans in extending best wishes to all those associated with KMOX Radio and good luck to the St. Louis Cardinals on what I know will be a most enjoyable and rewarding trip.

Richard M. Nixon

Vice-President1

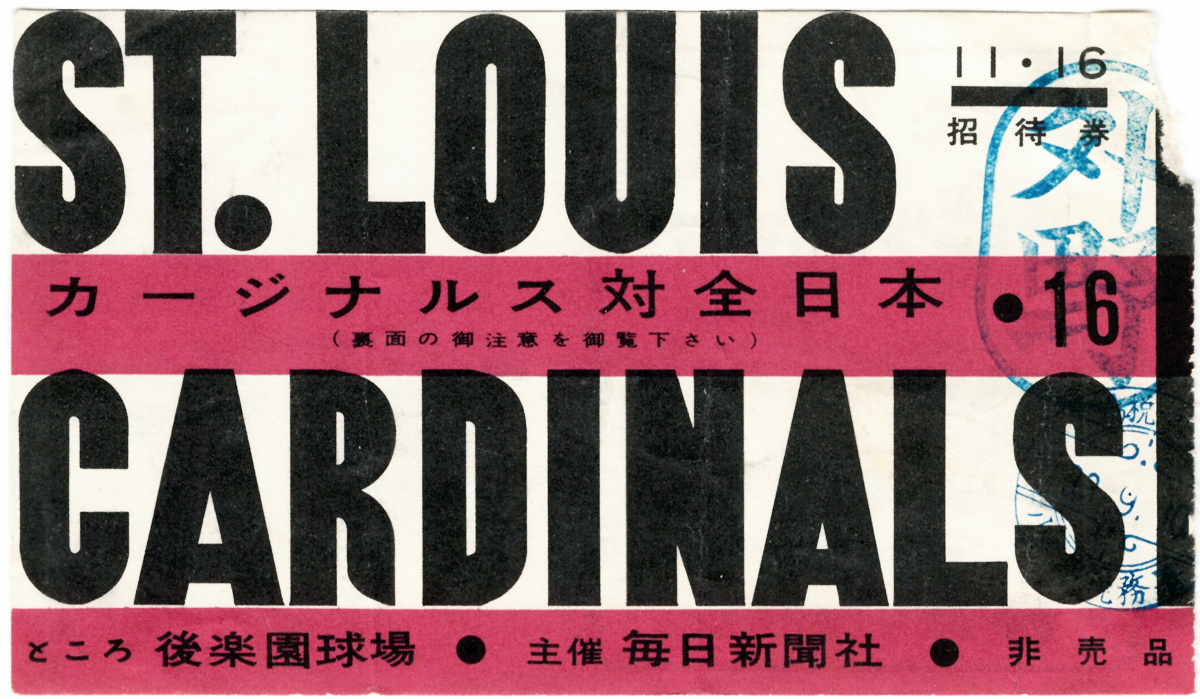

They played in Honolulu, Manila, Seoul, Tokyo, Sendai, Sapporo, Osaka, and Hiroshima; Shimonoseki, Mito, Fukuoka, and elsewhere. The average attendance was 25,000, including 40,000 fans for the two final games, a doubleheader in Tokyo. The team left by plane for Kahului on October 11, 1958, less than two weeks after the conclusion of a fifth-place finish in the National League.2 By the 13th they were in Honolulu, where Jim Brosnan had already submitted his first dispatch.

The St. Louis Cardinals had embarked on their 1958 tour of Japan in the midst of management changes and a rebuilding effort, the impending twilight of Stan Musial’s career and the dawn of a new age of Japanese baseball. Watching it all was Jim Brosnan, whose series of articles would be some of the first words written from the perspective of an American ballplayer on playing in postwar Japan. They would go on to form a literary foundation not only for his own writing, but for the future of baseball literature.

American pros had been visiting Japan for over half a century. The Reach All-America Team had visited in 1908, Herb Hunter’s All-Stars twice in the 1920s and once in 1931, as well as the Negro Leagues All-Star squad the Philadelphia Royal Giants and a major league All-Star team in 1931.3 The 1934 tour, however, outshone the rest in its grand scope as well as its importance to the foundation of professional baseball in Japan. The tour introduced, in the flesh, the almighty Babe Ruth to the baseball-hungry fans of Japan, gave birth to new heroes like Eiji Sawamura and, in the person of Moe Berg, played a role in international intrigue. It led to the formation of Japan’s first professional team and set the standard for diplomacy that would become the hallmark of the postwar tours.

In 1949, spurred on by the occupation government, the PCL San Francisco Seals became the first American team since the mid-1930s to play against teams in Japan, and inspired the expansion of the professional leagues into a two-league system the following year. More All-Star tours followed, including the Joe DiMaggio-led bunch in 1951 and the Eddie Lopat All-Stars in ’53, before the American and National leagues finally relented and allowed actual major league teams to tour after the season (bypassing a rule in practice for decades not allowing more than three teammates to barnstorm together after the season).4 All three New York teams took turns playing against a combination of established Central and Pacific league teams (usually headed by the Yomiuri Giants) as well as All-Star teams formed by various players.

After several visits from New York teams 1953–57, the Cardinals’ tour of 1958 stands out as the first to represent the rest of the majors. Mainichi Newspapers proposed that the ’58 tour include a number of changes to coincide with the Cardinals, including a fully representative group of Japanese All-Stars to play the majority of the games.5 The fifth-place Cardinals had not been a powerhouse for most of the decade. Despite the star power of Musial, the tour was really a vehicle to show off the new era of talent in Japan against an established team from the United States.

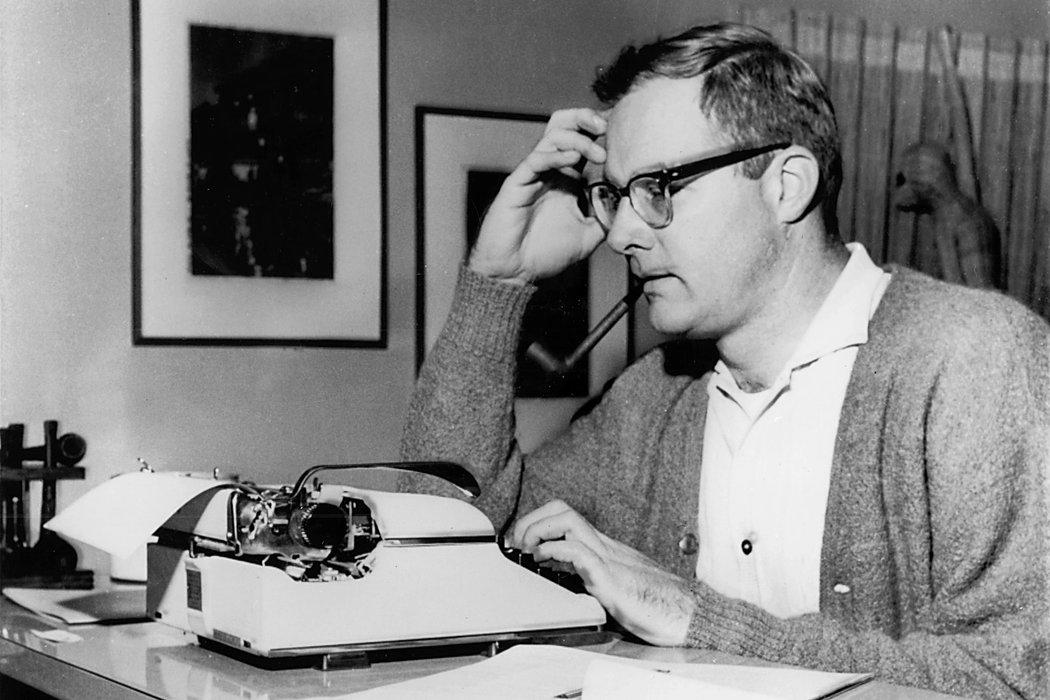

After “The Long Season ” was published, author Jim Brosnan was called a “kookie beatnik” by Joe Garagiola and “an intellectual meathead” by Frank Lane, the general manager of the Indians. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

THE PROFESSOR

Ignominy! For Shame! Fie on us! In the cold, cold city of Sendai, where the other touring United States clubs have had a rough time, the Cardinals bit the mud (it’s still raining) for the first time since leaving the U.S.A. Solly Hemus, previously undefeated as Cardinal manager, has thus suffered the first stings sic] and arrows of outrageous fortune. To the smiling, bowing Japanese press Solly graciously admitted — “We gave ’em the game.” — Jim Brosnan, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 2, 19586

Though he was on the planes and in the bullpen and at the cocktail parties, Jim Brosnan did not make a pitching appearance against the Japanese stars until November 3 in Osaka, when he pitched a perfect 10th inning after future congressman Wilmer “Vinegar Bend” Mizell almost lost the game in the ninth.7 Brosnan had eased into the relief role in his three major league seasons with the Cubs after starting out in pro ball in 1947 as a 17-year-old in the Appalachian League.

After pitching the Cubs to an Opening Day victory over the Cardinals in April 1958 (over future teammate Mizell), Brosnan had been traded to St. Louis for Alvin Dark in mid-May, an event Dark “had considered a grave insult.”8 That season all his appearances were as a starter. No longer would he spend all his time in the bullpen, alone with his thoughts and his pen. Instead, he would start all of his Cubs appearances and, beginning in May with the Cardinals, he was made a spot starter, finishing the season 11–8 with seven saves. Though a swingman, he still had time to keep writing, which was more and more at the forefront of his ambition.

Brosnan had spent close to two years in the Army in the early ’50s, where he had discovered an aptitude for writing to go along with his lifelong love of music. After making it to the majors, he continued to pursue this avenue through short pieces that eventually led to a relationship with Bob Boyle, whom he met when Boyle visited the Cubs on assignment from Time magazine to write a piece about Philip K. Wrigley.9 Boyle, who also wrote for Sports Illustrated, encouraged Brosnan to submit a diary about his trade to the Cardinals, which was subsequently published in the July 21, 1958, issue of SI (titled “Now Pitching for St. Louis: … The Rookie Psychiatrist”).10

It was a revelation — a player thinking, recording, and publishing his thoughts on the game. No doubt it also ruffled a few feathers. After the success of “The Rookie Psychiatrist” and another piece, “Me and Hutch,” Bob Creamer, an editor at Sports Illustrated, approached Brosnan to write a series of articles about the upcoming goodwill tour of Japan. Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch subsequently learned of the agreement and offered Brosnan a chance to write a series of articles on the same topic, for which he would pay $100 per dispatch.11 Known as a pitcher, it was as a writer that Brosnan really wanted to be remembered.

Though intellectual pursuits were not generally associated with the life of a ballplayer, Brosnan’s ambitions were not unprecedented. Throughout baseball history, there had been a few ballplayers, most notably Sol White and John Montgomery Ward, who were known to both play and write. There had been many books “authored” by players both well-known and otherwise, but they had been ghostwritten, usually by sportswriters such as Ford Frick. This includes Pitching in a Pinch by Christy Mathewson, though ghostwritten by John Wheeler, which is considered one of the first “tell-all” baseball books.

Needless to say, baseball books were not taken seriously, with one exception: Ring Lardner, a respected sportswriter and friend of F. Scott Fitzgerald, wrote a series of short stories based on the “busher” Jack Keefe, as well as what is probably the first respectable baseball novel, You Know Me Al.12 Other than Lardner’s Keefe, baseball fiction was dominated by the all-American, goody two shoes, Frank Merriwell type, and aimed at bolstering the notion of heroism to boys across America.13 It wasn’t until after World War II that the first serious group of baseball novels emerged. In 1952, Bernard Malamud, a master of the short story, published The Natural, a book as much about American myth and magic as about baseball. The long history of baseball literature up to that point, focused on perpetuating the myth-building essential to the culture, served as a perfect canvas for Malamud’s allegorical Roy Hobbs.

The other significant baseball novel published at roughly the same time, The Southpaw (1953), took a different approach. Author Mark Harris had written about baseball in essays and stories for a decade, with a perspective rooted in the realism of the game’s place in American culture. His book proved to be a kind of anti-Malamud, and his protagonist the anti-Roy Hobbs. Henry “Author” Wiggen spoke in a vernacular much closer to the everyday speech heard on a ball field than was typically seen in print, and, in a way, harked back to the style popularized by Lardner’s Jack Keefe.14

Jim Brosnan was Author Wiggen. Just as Wiggen was known as “Author,” Brosnan was known as “The Professor.” He saw himself as a writer as much as a pitcher, and he even looked the part, with his thick glasses and books under his arm. The two authors knew each other’s work — Brosnan had reviewed Harris in an obscure journal called Etcetera back in the mid-’50s, a piece that had jump-started his own literary career.15 Harris would review The Long Season for the New York Times in 1960, praising Brosnan’s gift to literature and baseball — a glimpse into the mind of the average ballplayer. Harris wrote: “Fortunately, however, [Brosnan’s] enthusiasm for the game is at least equaled by his passion for observing, for listening and for recording who said what to whom and why in what bull-pen where, how the Cincinnati Reds fare at bridge, how the airline hostess responds to Mark Twain’s literary criticism, what it feels like to be booed; the nature and extent of racial integration among big-league baseball players; the relationship between Team and Self. ‘Carefully I preserve these artifacts of an expiring career.’”16

Harris, the anti-Malamud, had written his books in the voice of such a player, and that writing had influenced Brosnan’s voice — and, in a cyclical nature, so too had Brosnan’s voice, that of “the thousands of baseball players not blessed with extraordinary gifts who will never knock at the door of Cooperstown,” influenced Harris. In The Long Season, Harris sees the positive in the brainy Brosnan’s “dwelling intimately upon the particular, tell[ing] us much we have never been able to know of the mute thousands.”17

These similarities help explain Brosnan’s “character.” That character took shape first in his diaries, and then in the dispatches sent from Japan. “I had not been happy with the baseball books that I had read when I was a kid,” he told an interviewer later in life. “I wrote about what interested me — what I overheard in the clubhouse. … The editors said, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing.’”18

Sports Illustrated ended up passing on whatever Brosnan submitted to them after the tour, but the effort resulted in another meeting with Creamer. Not only did Creamer provide “The Professor” with an impromptu journalism lesson, he proposed a meeting between Brosnan and a friend of his at Harper & Row. That meeting would eventually produce a contract and post-war baseball’s first notable book by a player, The Long Season.19

“Initially, I was told to take out [the references to] martinis. Then I got a call from the top editor … and he said ‘Ignore that last message. Put more martinis in.’”20

The Post-Dispatch was more than happy with the dispatches sent by Brosnan, and the published articles netted Brosnan over $1,000 in extra pay. The first dispatch, published on October 13 and titled “’Eastward, Ho!’ With Brosnan, Or, Getting Way Up With Birds,” set the tone not only for the remaining articles, but for the diary Brosnon kept with the Cardinals during the ’59 season, which would become The Long Season. It exemplified the style of the rest, a free-form, literate style influenced by jazz but grounded in the real observational elements cherished by Harris and Author Wiggen.

A ticket stub to the final game of the tour. (Author’s collection)

THE FIRST DISPATCH

In early October 1958, Brosnan was headed to Honolulu, writing from the plane about the long flight and the stomach-churning reality of a 28-hour long, multi-time-zone day. He was already attempting to flex a sense of style. He began:

“From one of the longest runways in the world, San Francisco, we took off on the longest trip of this or any other year. By sunrise on the tenth we gained four hours changing time zones and explaining to the stomach wha’ hoppen in our 28-hour day.”21

His claustrophobia related not only to a lengthy plane ride but to the celebrity and status that were the reason for that plane ride, inexorably tying the two together for the reader. And he lamented the insurance value of his life:

“Gives a man a feeling of power to be worth more money dead than alive. Macabre, that describes this game.”22

He wrote of the “distractions” — the wives, yes, but especially the “stewardesses,” even going so far as to describe one’s outfit in detail, a segment demonstrating the kind of sexist overtones accepted as routine in the sports world of that time. He wrote, too, of the food, relating the size of the plane’s kitchen and its propensity for putting out “sizzling steak sandwiches” and breakfast. Still, with style, he remarked, “I mean this ship was big, man,” and piled on the self-deprecating humor: “Ignoring the champagne left over from the take-off party (man, what a tough way to make a buck) we prepared fresh morning coffee.”

Just as important as the cocktail parties was the Honolulu sunset:

Down the winding stairway I went to the lounge to watch the sunrise. As a working ballplayer, I don’t ordinarily cover sunrises, but I have seen some. This one was a first in one sense, however, an Oriental mirage perhaps, but I swore to myself that I was seeing a ring around the earth just above the horizon. Nothing but clouds, water and whales below, so I sat, in voiceless contemplation of the rising sun. (Fifteen years ago, I would have been shot for using the expression!)23

Brosnan was aware that most of his teammates, as well as most of the Japanese All-Stars, had come up in the aftermath of World War II, and were slightly less encumbered than ballplayers of the previous generation by the weight of the war’s prejudices, as well as the horrors of having participated. This was a new era dawning, and he saw clearly the hope that was at the heart of this diplomatic trip to Japan.

Yet other prejudices prevailed. Though Brosnan seems to avoid utilizing the racially insensitive language employed in headlines and coverage of the tour in the United States (for example, the Post-Dispatch headlines “Boyer Most Honorable Batter as Cards Beat Japanese in 10th” and “So-Sorry Cards Make Sad Sam at Home in Japan, Boot Game”), he was still a product of his time, employing tropes of women and Japanese ballplayers that would be perceived as insensitive today.24

He concluded with a lament on lost bridge partners — Del Ennis and Billy Muffett, scheduled to make the trip but traded just before takeoff, were half of a four-man game rounded out by Larry Jackson. But the beauty before him, Larry, and, of course, the cocktail parties and receptions, replaced any reverie for the past life or routine of the season, and set the tone, not just for Brosnan and the team but for the reader, that the best was yet to come.

“The problem of finding a fourth was not our concern immediately, though. Molokai, the leper colony island, was on our left, Diamond Head just a few minutes away, and the scent of jasmine was being wafted skyward from the island of Oahu.”25 The first three games were in Hawaii, against local stars and semipros led by Bob Turley, Lew Burdette, and Eddie Matthews, who had accompanied the Cards up to the Hawaiian stops. Strong fall rain forced the cancellation of a game in Guam, but otherwise the Cardinals shut out the opposition before boarding the plane to Japan.26

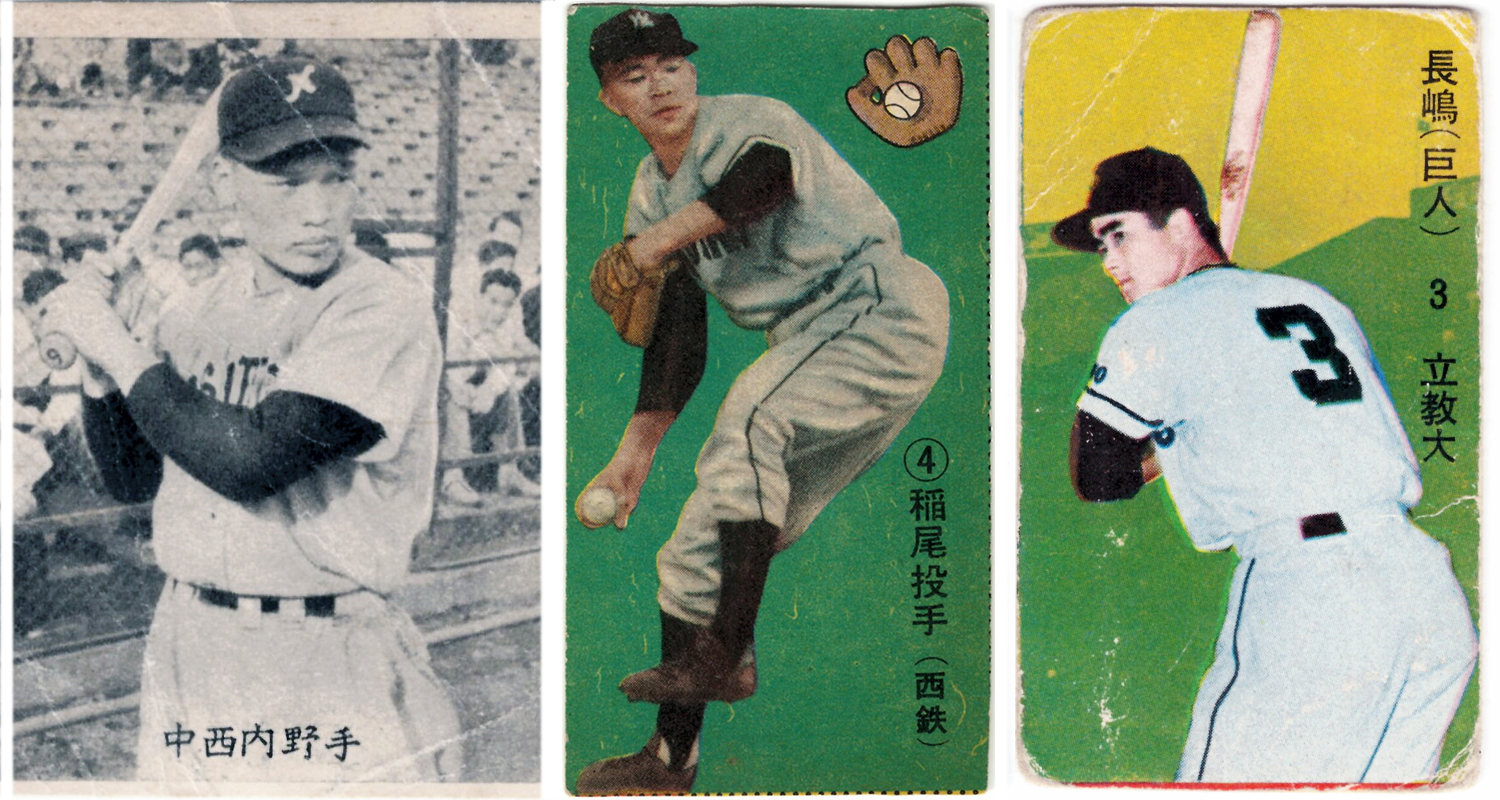

The Cardinals continued winning after arriving in Tokyo. However, the young squad of All-Stars from Japan’s Central and Pacific leagues did not disappoint. Futoshi Nakanishi of the Nishitetsu Lions hit several towering homers, including one off Vinegar Bend Mizell and a grand slam off Bob Blaylock, which secured one of only two victories for the Japanese squad.27 Kazuhisa “Iron Man” Inao pitched admirably considering he had come off of a season during which he pitched 373 innings and nearly single-handedly won the Japan Series for the Lions, pitching in six games and securing victories in all four team wins. But it was the rookie Shigeo Nagashima who would be unanimously voted the best of the All-Stars by the touring Cardinals.28 His clutch hitting, including an inside-the-park homer, and fine fielding at third base showcased not only the wonders of his own talent, but demonstrated to an international audience the level of skill to be found in the younger generation of Japanese pro ballplayers. He would go on to hit his famous “Sayonara Home Run” before the emperor the following year, and become known as “Mr. Baseball.”

Brosnan would write 11 further dispatches before the Cardinals headed home, describing the game and culture of Japan from a perspective only a player could represent. In the November 6 dispatch, he told of running into “Carl Hanta, a Nisei from Honolulu, with whom I played in the Texas League,” who would point out to Brosnan the “many differences not immediately evident” between baseball in Japan and in the United States.

“Carl played for one of the Japanese professional teams here, although he arrived too late this year to make the All-Japan nine. Did you know, he asked, that: ‘The average major league player in Japan makes about $100 a month? That nobody goes home after the season ends? The players remain in the club home town to train for next season? … That the Number One pitcher in the league makes twice as much money as the Prime Minister? That the typical youngster in Japan would rather be the No. 1 pitcher than Prime Minister?”29

And as Brosnan educated American fans about the game, he continued to develop his style, peppering in jazz and humor:

“Noro Morales — he’s the jazz man, Cats — attended one of our games. He says, if I may try to quote: ‘It was a gas, man. Those cats come on like they dig the up-beat, the down-beat and the off-beat. But dig the crazy infield. These cats are supposed to know how to sow the seed. And there it is, all skin, man! I mean it’s bare, boy! And hey, they put you down with the long ball. Like, let’s do the home-run bit. Like, Swingin’ Stan the Man — let’s swing, dads.’ Which all means, I think, that the Japanese really look the part of pro baseball players; that there is no grass on the infield because of clay in the soil; that the Japanese All-Stars hit two home runs and the Cardinals hit none, and that Morales knows about Stan Musial.”30

His dispatches would bring to life both the unique excitement and painful boredom of a professional ballplayer on tour in another country in a way that the press corps couldn’t. This included Joe Garagiola, who would later be critical of Brosnan’s writing, reporting on the tour for KMOX.31 Garagiola, as well as many other players (including Joe Adcock, who, after hitting a home run off Brosnan in the wake of The Long Season told Jim to “stick that in your book” as he rounded the bases), were upset by the reality reflected in Brosnan’s writing.32 However, it was that reality that made his writing, including his dispatches from Japan, so important. They introduced a world of baseball to an American audience mostly unaware of the level of talent competing halfway across the world. Names like Nagashima and Kawakami, “The Big Buffalo” and Iron Man Inao. Exactly as Author Wiggen might.

From left: Futoshi Nakanishi, Kazuhisa “Iron Man” Inao, Shigeo Nagashima. (Author’s collection)

GOTTA START SOMEPLACE

George Plimpton’s “small ball” theory of sports literature suggests that “the smaller the ball, the more formidable the literature.”33 As an example, he cites Brosnan’s writing and his insistence on realism. Known more for Paper Lion, as the founder of the Paris Review, and as a sullen New York Giants fan, Plimpton was what the Spanish call an espontáneo — a “haunted young man who starts moving down from his cheap seats toward the bullring … [to] run across the open sand” — in Paper Lion and his other sports books, including the baseball book Out of My League.34 In a way, Brosnan was a kind of reverse espontáneo, moving from the “cheap seats” of the bullpen to the “open sand” of the publishing world. The 1958 tour of Japan, which provided the Cardinals with a chance to travel and Brosnan a chance to once again prove his chops as a writer, served as a necessary building block in that process.

During the trip, several of the American pitchers were offered large contracts to stay and pitch in the Japanese pro leagues. Phil Paine and Bill Wight declined. The third Cardinal offered cash to stay was Jim Brosnan. He turned down the offer as well, thinking of his family. It was a good move.35 His 1959 season would prove excellent fodder for The Long Season, paving the way not only for the publication of Plimpton’s Out of My League in 1961, but easing the path for the success of baseball literature and its integration into American literature.

The publication of Jim Bouton’s Ball Four a decade after The Long Season was rightly hailed as a watershed moment in sports history. That Ball Four owes a certain debt to Brosnon is evidenced not only by its publication, but by the similar (though more visceral) reaction to it from the baseball community. Brosnan, as Bouton would be, was shunned after The Long Season was published, called a “kookie beatnik” by Garagiola and “an intellectual meathead” by Frank Lane, the general manager of the Indians.36 Brosnan’s personification of the Author Wiggen character, as well as the influence Harris’ writing had on his own, gave rise to his “tell-all,” “from-the-pitcher’s-point-of-view” and “espontáneo” articles in Sports Illustrated and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. The success of these resulted in his meetings with the eventual publishers of The Long Season.

Later in life he would correspond with Harris about his influence as well as Brosnan’s own career as a writer of children’s baseball books (in his words, “gotta start someplace”) and sports pieces. In a letter dated January 2, 1968, he addressed Harris: “You once suggested I keep a complete list of my published writings. Have done so. For ten years’ work the compendium now covers five pages: 52 magazine articles; 5 books; over 50 newspaper columns; a dozen reviews and essays; half a dozen re-prints; two prefaces and a pair of short stories.”37 It all started, though, with the Cardinals and Japan.

ADAM BERENBAK is an archivist in the National Archives Center for Legislative Archives. He earned a Master of Library Science degree with a focus in archives from North Carolina Central University and was a 2008 Frank and Peggy Steele Intern at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center in Cooperstown, New York. He has previously published “Congressional Play-by-Play on Baseball” in “Prologue” (Summer 2011 edition), and “Henderson, Cartwright, and the 1953 US Congress” in the Fall 2014 “Baseball Research Journal.” He has written informally about baseball in Japan for the past decade here: http://noboruaota.blogspot.com.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dan Lillienkamp of the St. Louis Public Library Special Collections and Curtis Small of the University of Delaware Libraries. This work is an excerpt of a longer work on the 1958 Cardinals’ tour of Japan on which the author spoke at the Cooperstown Symposium and hopes to publish as a full-length book. An exhibit featuring tour-related artifacts is planned for Summer 2018 at the Japanese Embassy Cultural Center in Washington, DC.

Notes

1 “Nixon Lauds Station KMOX for Airing Cardinal Games,” The Sporting News, October 29, 1958.

2 J. T. Taylor Spink, The Sporting News Baseball Guide and Record Book (St. Louis: Charles C. Spink & Son, 1959).

3 Daniel E. Johnson, Japanese Baseball: A Statistical Handbook (Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland & Company Inc. Publishers, 1999).

4 “Giants Invited to Become First Major Club to Make Baseball Tour of Japan as Unit,” New York Times, June 30, 1953.

5 Lee Kavetski, “Cards to Face 50 of Japan’s Best on Jaunt,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1958

6 Jim Brosnan, “Old Cardinal Refrain ‘We Gave ‘Em Game’ Heard Anew in Japan,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 2, 1958.

7 “Boyer Most Honorable Batter as Cards Beat Japanese in 10th,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 3, 1958.

8 David Davis, “An Interview with Jim Brosnan,” SoCal Sports Observed, July 17, 2007, http://www.laobserved.com/sports/2007/07/an_interview_with_jim_brosnan.php, last accessed January 17, 2018.

9 Charles Demotte, “Writing From The Bullpen: Jim Brosnan and Jim Bouton, Two Baseball Diarists,” Writing From The Bullpen, January 24, 2014 (https://chasdemotte.wordpress.com/, last accessed January 17, 2018.

10 Charles Demotte, “Writing From The Bullpen: Jim Brosnan and Jim Bouton, Two Baseball Diarists,” Writing From The Bullpen, January 24, 2014 (https://chasdemotte.wordpress.com/, last accessed January 17, 2018.

11 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: HarperEntertainment, 2000) 422-431.

12 Christian K. Messenger, “Expansion Draft: Baseball Fiction of the 1980s” in The Achievement of American Sport Literature: A Critical Appraisal, ed. Wiley Lee Umphlett (Rutheford, Madison, Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1991).

13 John A. Lauricella, Home Games: Essays on Baseball Fiction (Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland & Company Inc. Publishers, 1999).

14 John A. Lauricella, Home Games: Essays on Baseball Fiction (Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland & Company Inc. Publishers, 1999).

15 Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis, 422-431.

16 Mark Harris, “Between Pitches, There was a Lot to Think About,” New York Times, July 10, 1960.

17 Harris, “Between Pitches.”

18 Davis, “An Interview with Jim Brosnan.”

19 Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis, 422-431.

20 Davis, “An Interview with Jim Brosnan.”

21 Brosnan, “Boyer Most Honorable Batter as Cards Beat Japanese in 10th.”

22 Brosnan, “Boyer Most Honorable Batter as Cards Beat Japanese in 10th.”

23 Brosnan, “Boyer Most Honorable Batter as Cards Beat Japanese in 10th.”

24 Brosnan, “So-Sorry Cards Make Sad Sam at Home in Japan, Boot Game,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 27, 1958.

25 Brosnan, “Boyer Most Honorable Batter as Cards Beat Japanese in 10th.”

26 Red McQueen, “Cardinals Pound Burdette and Turley Before Small Crowds in Hawaii Games,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1958.

27 “Grand Slam Homer Hit Off Blaylock As Cards Lose 9-2,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 4, 1958.

28 Lee Kavetski, “Cardinals Vote Nagashima Top Nippon Player,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1958.

29 Jim Brosnan, “Firecrackers, Pigeons, Balloons Help to Start Game in Japan,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 6, 1958.

30 Jim Brosnan, “Tourist Brosnan Finds 65,000 Boy Scouts Lost in Japan,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 31, 1958.

31 John Corry, “No Comic Books For Brosnan,” New York Times, August 28, 1960.

32 Davis, “An Interview with Jim Brosnan.”

33 George Plimpton, “The Smaller the Ball, the Better the Book: A Game Theory of Literature,” New York Times, May 31, 1992.

34 George Plimpton, Out of My League (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1961).

35 Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis, 422-431.

36 Corry, “No Comic Books For Brosnan.”

37 Jim Brosnan to Mark Harris, January 2, 1968, Mark Harris Papers, Manuscript Collection No. 101; Series I: Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 2, University of Delaware Library, Newark, DE.