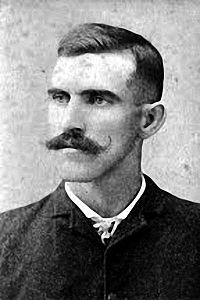

Cub Stricker

Cub Stricker was a nineteenth-century second baseman who played for seven different clubs over an 11-year major-league  career (1882-1885, 1887-1893). Affectionately referred to as Cub because of his diminutive stature – he was 5-feet-3 inches tall and weighed between 135 and 140 pounds – the right-handed-hitting and -throwing Stricker was considered an average hitter with fair speed who covered a great deal of ground defensively.1 Stricker’s feisty style of play personified the grit and determination that the 1883 Philadelphia Athletics exhibited on their run to the American Association title.

career (1882-1885, 1887-1893). Affectionately referred to as Cub because of his diminutive stature – he was 5-feet-3 inches tall and weighed between 135 and 140 pounds – the right-handed-hitting and -throwing Stricker was considered an average hitter with fair speed who covered a great deal of ground defensively.1 Stricker’s feisty style of play personified the grit and determination that the 1883 Philadelphia Athletics exhibited on their run to the American Association title.

John A. Stricker was born on June 8, 1859, in Philadelphia to William and Rachel Stricker. According to the 1870 Federal Census, William worked as an “iron moulder,” while Rachel stayed home, “keeping house.” John was the youngest of what is believed to have been six children in the household, although records are unclear on this subject. The family lived in the eastern part of the 17th Ward of Philadelphia. John did not attend college, and began his professional baseball career in 1882 with the Athletics.

In Stricker’s debut, on May 2, 1882, the Athletics defeated the Baltimore Orioles 10-7 in Philadelphia’s Oakdale Park. Stricker batted eighth and walked twice, stole a base, and scored two runs. The stolen base came at a particularly opportune time, in the eighth inning with the Athletics trailing 7-6. After stealing second, Stricker took third on a muff of the throw and then proceeded to score the tying run. Wrote the Philadelphia Inquirer, “The game was full of errors, many of them being excusable from being sharp hit and bounding balls, which were very difficult to judge.”2 That was a generous description of the contest, as the teams combined for 23 errors. The game also included a scary moment: Athletics catcher Jack O’Brien was briefly knocked unconscious after being struck in the neck by a foul tip but “after a short recess, O’Brien pluckily resumed his position and played the game out.”3 The newspaper aptly described the game as “very exciting.”4

Overall, the 22-year-old Stricker had a solid if unspectacular rookie season in professional baseball, batting .217 with no home runs, 18 RBIs, and 34 runs scored. He made 52 errors at second base and appeared in two games as a relief pitcher, totaling seven innings pitched and a 1.29 ERA. While he continued in future seasons to commit a high number of errors by today’s standards, he completed his career with a fielding percentage of .907 as a second baseman and was known as one of the more accomplished second basemen of his time. The Athletics finished the 1882 season in second place, with a 41-34 record.

Stricker improved significantly in his sophomore season, batting .273 with one home run and 40 RBIs in 89 games. The 1883 Athletics also saw an uptick in their performance, and won the AA pennant with a record of 66-32, one game ahead of the St. Louis Brown Stockings. Stricker continued to play with the Athletics through the 1885 season before joining the Atlantas of the Class-B Southern Association in 1886. Eight teams made up the league – Atlanta, Augusta, Charleston, Chattanooga, Macon, Memphis, Nashville, and Savannah.

Blondie Purcell managed the Atlantas, who finished in first place. As for Stricker, the Atlanta Constitution reported, “The playing of Stricker at second base could not be equaled. His batting and base running was the finest ever seen south.”5 Another time, the newspaper called Stricker “unquestionably the best second baseman ever seen in Atlanta.”6 For the season, Stricker played in 85 games and recorded a .243 batting average with 50 runs scored, 58 stolen bases, and 4 home runs. He also pitched 7⅔ innings in two games and compiled a 1.17 ERA. Besides winning the pennant, Atlanta became the first team to play a game without an error, and Stricker hit the first home run in the league.7 The league lasted just one season. The Times of Philadelphia, reporting on September 5 that the league had folded, called it “a disgrace to base ball this year,” saying a number of players had caused trouble related to issues such as drunkenness, and adding that the reputation of some umpires was less than stellar.8

On November 7 two American baseball teams left for Cuba to give enthusiastic Cuban baseball players lessons about playing the game. There were three baseball clubs in Havana, which played in a championship series in February. The American teams, named “Philadelphia” and “Athletic,” gave their lessons at Matanzas and Cienfuegos. Stricker played second base for the “Philadelphia” team.9

From 1887 to 1889 Stricker played for the Cleveland Blues. The Blues played in the American Association in 1887-88, then moved to the National League in 1889 as the Cleveland Spiders. Stricker was the captain of the team in 1887, and on June 14, in a return to his old stamping grounds in Philadelphia, fans showed their affection for him when they gave him a standing ovation and a basket of flowers with an eagle topping the basket. The Spiders defeated the Athletics, 6-4. Stricker batted leadoff and got a hit, stole two bases, and scored a run.10 For the season Stricker batted .264 with two home runs and a career-high 86 stolen bases. The Spiders, however, concluded the season in eighth (last) place with a record of 39-92.

Stricker followed his debut season with Cleveland with another solid campaign in 1888, playing in 127 games and amassing 115 hits for a .233 batting average with 60 stolen bases and a career-high 12 innings pitched. He committed 57 errors at second base, an improvement from the 80 errors he made at the position in 1887. The Spiders fared marginally better as a team in 1888, finishing with a 50-82 record and in sixth place in the American Association. When the team joined the National League in 1889, it was greeted with skepticism. The St. Louis Post Dispatch lamented, “What on earth will the League do with Cleveland? It once proved a failure as a League city, and is a no better ball city now than then.”11 This sentiment proved to be well founded; the Spiders stumbled to a sixth-place finish with a 61-72 record. But they were noted for a strong infield and the Press Herald of Pine Grove, Pennsylvania, identified Stricker as a bright spot, writing in July that he “so far has outplayed all the League second basemen.”12 The Salt Lake Herald also touted Stricker’s defensive abilities:

The star of the infield is Stricker, known also as the “Cub,” for the reason, no doubt, that he is 30 years old and rather short in stature. … He is a fair batter, a most marvelous fielder, and a base runner of the first grade. In his position he has no superior. He always plays a magnificent game. 13

The 1890 season brought with it great strife and change within the game. A third major league, the Players League, was formed as a protest of what players believed had been unfair treatment by team owners. Stricker wanted to jump to the league’s Cleveland Infants for the 1890 season, but the Spiders sued him, declaring that the reserve clause in his contract bound him to them.14

Many other clubs filed lawsuits against players attempting to enjoin them from jumping to the Players League. However, multiple court rulings refusing to enjoin player movement on these grounds, most notably in the case of Brotherhood leader John Montgomery Ward, convinced teams to no longer pursue such suits as they related to the 1890 season and Stricker was permitted to play for the Infants. The Boston Globe referred to Stricker during the season as “one of the most outspoken brotherhood players in the country.”15 The Infants finished in seventh place in 1890 with a 55-75 record. Stricker turned in a .244 average in 127 games, with a career-high 65 RBIs.

Lack of financing doomed the Players League after one season, and Stricker was once again looking for a new home. He found it with the Boston Reds of the American Association, who used manager Arthur Irwin to recruit Stricker.16 With the Reds, he continued to be recognized as a superior second baseman. The Boston Globe’s early-season appraisal: Stricker “is every ounce a ball player and a pound or two over. His great work at second gained him the applause of the afternoon, and his head work on several instances could only be appreciated by thorough cranks of the game.”17 Stricker’s play contributed to a championship season as the Reds’ 93-42 record surpassed the second-place St. Louis Browns by 8½ games. Stricker played in 139 games and hit .216 with 54 stolen bases.

Just a year after navigating the folding of the Players League, Stricker once again was forced to change teams when the American Association went out of business after the 1891 season. He was assigned to the St. Louis Browns, where he was named the team captain.18 He lasted only 23 games with the team, however, and was stripped of his captaincy after he jumped into the stands and punched a fan who had been heckling the team.19 He was quickly traded to Pittsburgh for pitcher Pud Galvin.20 Stricker never played for the Pirates; he was again quickly dealt, this time to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher William “Adonis” Terry.21 The Orioles finished dead last with 46 wins and 101 losses, 54½ games behind the pennant-winning Boston Beaneaters. Though the Orioles played poorly, Stricker posted his highest batting average since 1887, hitting .264 during his time with the Orioles.

A lowlight of Stricker’s season occurred on the night of August 4 in the reading room of the team hotel in Boston, the United States Hotel. Stricker and outfielder William “Jocko” Halligan had been good-naturedly razzing each other when the substantially larger Halligan left the room, returned, and without warning struck Stricker in the face.22 Stricker later claimed that the fight was as much his fault as it was Halligan’s, but it was Stricker’s right cheekbone that was broken and Halligan who was suspended without pay for the remainder of the season.23 Despite the injury, Stricker was advised to sit out only one game, which the Orioles lost 6-4. Club Vice President John Waltz acknowledged, “Without Stricker we are without a head.”24

After the season Stricker packed his baseball suitcase once again, joining the Washington Senators for the 1893 season. It was an abbreviated season for Stricker, who played in only 59 games and once again proved unable to avoid controversy. On August 5 the Senators were in Philadelphia to take on the Phillies. A contingent of fans in the right-field stands had been heckling Stricker for much of the game, and a faux cheer arose from the crowd after he made a nice catch of a difficult fly ball. This was apparently the last straw for the second baseman turned outfielder. Stricker attempted to scare the fans by throwing the baseball at the fence in front of them, but the ball skidded over the railing and struck fan William Wright, breaking his nose and knocking him out. Stricker was “quietly arrested and taken to an adjoining station house, where he was subsequently released on his own recognizance.”25 At the end of October, the case went before Philadelphia’s Common Pleas Court, where it turned out that Wright was not exactly a model citizen. The court denied the request to have Stricker arrested again and decided that he should pay no court costs.26

The lowly Senators struggled through a miserable season themselves, finishing in last place with an anemic 40-89 record. They ended 46 games behind Boston. For Stricker, his final major-league season was unquestionably his worst, even without considering his legal troubles. He hit only .179, managing only 39 hits in 218 at-bats. Stricker was not yet ready to give up the game, however, and joined Providence of the Eastern League for the 1894 season. The club finished in first place with a 78-34 record. In 108 games, Stricker batted .282 and recorded 123 hits, 88 runs scored, and 52 stolen bases. He stayed with the team in 1895 as well, continuing to provide solid second-base play.

In 1896, Stricker was released by Providence and caught on with Pottsville of the Pennsylvania State League. Stricker was the team captain. He also played a short stint for the Springfield Maroons in the Eastern League, even playing through a broken finger so that he would continue to be paid. Toward the end of the season, he played for a third team, in Norristown, Pennsylvania. Despite his ever-advancing age, Stricker bounced around Pennsylvania with a number of amateur teams for years in such places as Philadelphia and Norristown. When he played with the Philadelphia Professionals in 1904, he stole four bases on April 30. Stricker also got a hit, and his team won by a score of 15-8. He even played second base in Cumberland in 1912 at age 52!27

Throughout his baseball career, Stricker was well known for bunting, as a place hitter, and for his speed in completing double plays.28 He was also notorious for convincing umpires to call a runner out despite only having bluffed a tag. After one game where four visiting runners had been called out going to second base when “to everybody in the stands, it looked as if Cub never got within 10 feet of a man,” Stricker was asked how many of the runners he actually touched. He replied, “What’s the use of touching ’em and running the risk of getting spiked. … All you got to do is to make a pass at ’em and then roll the ball back to the pitcher. Honest, there ain’t an umpire in this league who can see further than his nose.”29

After another game in which Harry Stovey, whom Stricker called “the best base stealer that ever lived,” was called out three times at second base, Stricker said, “I’ll hold up my right hand today and swear that I didn’t come within six inches of touching him once.”30 He added, “[W]hat a snap the infielders had back in my day. Why, I didn’t put the ball on one out of four of the base stealers when I was playing second, but I almost always got the decision.”31

Stricker worked as a milk wagon driver during the offseason for a number of years during his playing days, and continued to do so even after leaving professional baseball. The 1910 US Census lists Stricker as a real estate agent. In 1890, at age 30, he married a woman named Hannah, age 42. Stricker and Hannah had no children, and lived in Huntingdon Pike, Rockledge, Pennsylvania. This Census also listed Mary Meister, Hannah’s widowed sister, as living in the couple’s home.

Stricker died at age 77 on November 19, 1937, from a combination of bronchopneumonia, generalized arteriosclerosis, and myocardial degeneration. He is buried at West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, as is Hannah, who died from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 90 on January 26, 1939.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Retrosheet.org, Ancestry.com, and Baseball-Reference.com. I would also like to acknowledge the research of Michael Wagner and Paul Hofmann, which contributed greatly to this piece.

Photo credit: Courtesy of John Thorn.

Notes

1 “The Home Team: Sketch of the Men who Constitute the Local Teams,” Sporting Life, April 15, 1883: 2.

2 “The Athletics Win the First Game from the Baltimores – Other Contests,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 3, 1882: 3.

3 “The Athletics Win the First Game from the Baltimores – Other Contests.”

4 “The Athletics Win the First Game from the Baltimores – Other Contests.”

5 “The Atlanta’s Victory,” Atlanta Constitution, April 16, 1886: 8.

6 “A Good Game,” Atlanta Constitution, May 18, 1886: 8.

7 “First on Records for 1886,” Boston Globe, April 14, 1886.

8 “Base Ball News.”

9 “Base-Ball,” Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1886.

10 “Today’s Games,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), June 15, 1887.

11 “Base Ball Brevities,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 20, 1888: 7.

12 “The National Game,” Press Herald (Pine Grove, Pennsylvania), July 19, 1889: 1.

13 “The Diamond Field,” Salt Lake Herald, August 20, 1889: 2.

14 Gossip of the Ball Field,” Sun (New York), March 2, 1890: 5.

15 “‘Spiders’ in Town,” Boston Globe, May 16, 1890: 3.

16 “Stricker for Second,” Boston Globe, February 11, 1891: 7.

17 “Orioles Warble,” Boston Globe, April 24, 1891: 9.

18 “Over 13,000 Persons See the Cleveland-Cincinnati Game,” Boston Globe, May 2, 1892: 5.

19 Mike Eisenbath, The Cardinals Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), 361.

20 “Stricker Traded for Galvin,” Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1892: 6.

21 “Juggling Over Player Genins,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1892: 7.

22 “Halligan’s Quick Anger,” Washington Evening Star, August 5, 1892: 8.

23 “Halligan’s Quick Anger.”

24 “Halligan’s Quick Anger.”

25 “Stricker Lost His Temper.”

26 “Cub Stricker’s Capias,” Times (Philadelphia) October 28, 1893: 6.

27 “New Cumberland Wins,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 5, 1912: 12.

28 “John Stricker,” Boston Globe, August 14, 1904.

29 “Hot Air Is Cooled by Water Pitcher,” Oklahoma News, December 10, 1906: 3.

30 “Foxy Ball Player Was ‘Cub’ Stricker,” Evening Star, September 5, 1908: 9.

31 “Foxy Ball Player Was ‘Cub’ Stricker.”

Full Name

John A. Stricker

Born

June 8, 1859 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

November 19, 1937 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.