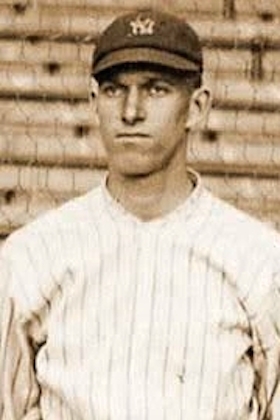

Ben Shields

Ben Shields threw left-handed but batted from the right side, rather than the more customary “bats left/throw right.” He was born in North Carolina, but died in South Carolina. He pitched for the New York Yankees and then for the Boston Red Sox. He almost lost his life to tuberculosis between his stints with the Yankees and Red Sox. Over a span of eight years in the majors, he was 4-0.

Ben Shields threw left-handed but batted from the right side, rather than the more customary “bats left/throw right.” He was born in North Carolina, but died in South Carolina. He pitched for the New York Yankees and then for the Boston Red Sox. He almost lost his life to tuberculosis between his stints with the Yankees and Red Sox. Over a span of eight years in the majors, he was 4-0.

“Big Ben” was born as Benjamin Cowan Shields on June 17, 1903, in Huntersville, North Carolina, a town just north of Charlotte. His family lived and worked on a farm just a few miles out of town in a Mecklenburg County community called Long Creek. Father Cowan Lemley “Lem” Shields was a farmer. He and his wife, the former Julia Nancy Alexander, raised Ben as the seventh of their nine children. Six of them were boys, not quite enough for a full baseball team. But at age 20, Ben Shields was pitching for the New York Yankees. He is listed at 6-foot-1 and 195 pounds, though he self-reported his height at an inch and a half taller.1

Shields attended Long Creek elementary school and Huntersville High through 11th grade, then completed two years at Oak Ridge Institute.2 Other Oak Ridge cadets who played in the major leagues include Wes Ferrell, Turkey Tyson, Ray Hayworth, Red Hayworth, and Billy Joe Davidson.3

Shields had been playing semipro ball in 1923 when he was signed by Yankees scout Paul Krichell “for $1,000 on a day he struck out a hot-shot third baseman that Krichell had come to scout.”4

The Yankees had not yet won a World Series, but hoped to do so in 1923. Shields was on board as a reserve. He threw batting practice to the team, but on his first full day on the job Babe Ruth had struck a ball that may have landed Shields in and out of hospitals for some years. As Shields later told it, “I joined the Yankees in Washington in 1923. I pitched batting practice the next day and Babe Ruth hit a shot back at me. It hit me in the right side of my chest, but I was 19 at the time and also rough and rugged so I shook it off.”5 (A couple years later, Ruth hit three homers, each helping win games for Shields.) He can be seen in a team photograph that ran nationwide after the team had clinched the pennant that year.6

On October 8, as the Yanks and New York Giants prepared to do battle with each other for the third straight year in the 1923 World Series, Yankees manager Miller Huggins had Shields ready. “Huggins worked all of his pitchers,” reported the Washington Post, of the practice session, “giving Herb Pennock, the southpaw, the longest stay on the hill. After him came another lefthander, a Carolina youth by the name of Shields.”7 It was a close, well-fought Series, and Pennock won two games, saving another. Shields had a great seat to watch the action but he wasn’t called on to take the mound. He did, however, leave New York with a portion of the half-share voted to be divvied up between him, a player named Lou Gehrig who also saw no postseason action, the trainer, the traveling secretary, and the groundskeeper.8

In 1924 it looked as though Shields would battle it out against Ben Newberry for a shot as the second lefthander on the pitching squad. Shields showed better than Newberry, and gained the edge. It was written that Huggins would take him north, if only to work more closely with him. “Shields has several faults which the manager wants to correct and he wants to do it before the Carolina southpaw gets back to the minors, where the habits might become so firmly fixed that they could never be changed.”9

Shields was with the team when the 1924 season opened. He didn’t stay long. He worked in two games. The first was on April 17 in Boston, coming into a game the Red Sox were leading, 5-1, and pitching the seventh and eighth, leaving it with Boston up, 9-1. In two full innings, Shields got through the seventh without the Sox scoring but in the eighth, he was hit for four earned runs on three hits and two bases on balls. He struck out three in the two innings of work. Three days later in Washington, the Senators were up 8-1, four runs each scored off Bob Shawkey and Sam Jones. Jones had taken over for Shawkey to work the seventh but couldn’t get anyone out. Shields took over for Jones and faced three batters. He couldn’t get anyone out, either, touched for three hits. All told, he’d faced 13 batters for the Yankees and eight of the batters reached base. Shields was charged with six runs and bore a 27.00 earned run average as he headed back to the minor leagues for more seasoning.

On April 26, 1924, Shields was released to Pittsfield (Eastern League). Existing (but perhaps incomplete) records show him as 0-2 for Pittsfield. He may have left the team for medical treatment, because we find a note that he was reinstated by Commissioner Kenesaw Landis on February 20, 1925.10

If there was any medical treatment, it seems to have worked. Under a verbal agreement between the Richmond Colts and the Yankees, Shields pitched for the Colts in 1925, leading the Virginia League in wins with 21 and in strikeouts with 187. Richmond won the pennant. He was 21-14 with a 3.15 ERA. And right after Richmond won the pennant, he celebrated by marrying Miss Emily Stoddard of Richmond on September 12. He pitched in a postseason set against Spartanburg.

The Yankees asked for him to come to New York after the playoffs and Colts owner H. P. Dawson agreed, even though another club had reportedly offered thousands of dollars for Shields. Dawson remained true to his word, however. 11

He was perhaps a little anxious his first time out; in one inning, he walked three but also recorded three outs and no runs scored. Given a start on September 24 against the White Sox, he pitched a complete game 6-5 win, going all 10 innings before his teammates pinned down the win for him thanks to a grand slam by Babe Ruth after Shields had let Chicago take a 5-2 lead in the top of the 10th. Four days later he won another complete game, this time 7-6 against the Tigers. He was giving up a lot of runs, but getting just enough offensive support to come out on top. Without Ruth’s first-inning solo home run, Shields wouldn’t have won the game. And he went to 3-0, throwing the final four innings of the October 3 game against the visiting Philadelphia Athletics, though yielding two runs. Ruth had hit a home run in the fifth inning of what became a 9-8 Yankees win. Shields finished the season 3-0 with a 4.88 ERA.

There were recurring medical problems. Near the end of 1925 Shields started to hemorrhage and had to be hospitalized. “X-rays showed that the line drive Ruth had hit off Shields’s chest had damaged his lung, which became infected over the two-year period.”12 Given a diagnosis of tuberculosis, he voluntarily retired from the game.13

New York signed him again for 1926 even though he was expected to be out the full year at his home in Richmond.14 He reported to camp, however. A big man (weighing 195-205 pounds), he looked “thin and not overstrong.”15 After about a week, it was clear that Shields wasn’t ready. He departed for Salem, Virginia, “to rest for six months and take treatment for tubercular trouble.”16 He was treated at Ridge Crest Sanitarium, then at a city hospital.

Shields was lucky to survive. In notes he provided in response to an inquiry from the Hall of Fame, he indicated he was in hospital taking a rest cure for four years, from 1926 through 1929. The TB, he said, “developed through the chest injury.”17 He said that Col. Ruppert of the Yankees paid his $1,800 salary throughout.

At some point during recuperation, Shields moved back to Richmond and began driving a taxi. Miller Huggins had thought he might have had another Herb Pennock in Shields, but TB prevented anyone from ever finding out. In December 1928, the Yankees cut all ties, enabling Shields to be a free agent if he were truly able to regain full strength. Reached by a reporter, he said he expected he’d need to sit out 1929 and 1930 as well, but thought he could be ready to play by 1931.18

As it happens, Shields came back in time to make the Red Sox in 1930. Manager Heinie Wagner marveled, “If that fellow has been sick for the past three years, then it must have been just too bad when he was healthy.” Shields was, the Boston Herald added, “about as rugged-looking a mortal as one could find outside the wrestling game.”19 Shields had written directly to Boston owner Bob Quinn to ask for a chance. Quinn checked with New York’s Ed Barrow, who said the Yankees held no claim. Quinn invested $150 to pay his expenses for Shields to come to camp in Pensacola.20

His first game for the Red Sox came on May 18, against the Yankees. He was the third pitcher at Fenway Park that day. When he came in, the Yankees already had an 8-0 lead. He threw the final five innings, giving up three more runs. The Red Sox never scored any. He pitched one inning in the first game of the May 21 doubleheader in Washington, giving up two runs, and the next day pitched four innings in the second game of another doubleheader. Those were his only three appearances for the Red Sox, leaving him with a 9.00 ERA in a Boston uniform. On June 10, his contract was sold outright to St. Paul. Yet another report a few weeks later said he was sent from Pittsfield to Buffalo on July 3.21

He appeared in just one game for Buffalo in 1930, noting that in retrospect he had “not enough time after hospital stay.”22 He was a free agent again by 1931 and tried out for the Phillies, who signed him in mid-February. He made the team, but his first outing was really rough. He faced six New York Giants batters, got no one out, and saw five earned runs score. In his second outing, he improved his earned run average from infinity to 94.00. Two outs, and two earned runs – but that was an improvement. His best outing was his third one – four innings of one-hit ball, with no runs scored. The Pirates led when he came in, but the Phillies – scored four runs on his watch, so Shields went home that night with a win. He only appeared in four games for the Phils. In his last game he gave up two runs in 2/3 of an inning. His ERA in the four appearances was 15.19.

As best we can determine, he did not play in organized ball again in 1931, though he did pitch for Richmond in 1932 and then, after the league disbanded on July 17, for Omaha. He’d reportedly put on weight after the bout with TB and was listed as 230 pounds in 1932.23 It appears to have been his last year in the game, though he’s seen in a preseason photograph of the 1933 Charlotte Hornets.

After baseball, he went into farming and real estate. He reported marrying Margaret Parsons in 1942, a second marriage. They had two children, Robert and Sandra.24

When he registered for the draft in World War II, he reported working for Southern Bearing and Parts Co. of Charlotte. Later, he built his own business, Shields’ Appliance and Services, serving the Charlotte area.

After losing his wife in 1974 and surviving a serious operation that same year, he moved into a mobile home next to his sister-in-law and her husband, and spent his time fishing. Shields’s experience with tuberculosis did not prevent him from living a long life. Shields died on January 24, 1982, in Woodruff at the age of 78. He is buried in Huntersville.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Shields’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Ben Shields player questionnaire, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 Greensboro Daily News, February 16, 1924. The New York Times of December 28, 1923 had cited Oak Ridge College, but then the February 2, 1924 New York Times said he had gone to North Carolina College, though it’s difficult to find an institution named that at the time, and Shields himself did not mention it. The February 16 Times called him George Shields, a southpaw. The Greensboro Daily News later called him “the ex-Oak Ridge sidewheeler.” See the April 10, 1924 edition. The Greensboro Record of January 26, 1933 also mentioned Oak Ridge, crediting Dr. Earl Holt with his development. Jim Savage, Director for the Oak Ridge Military Academy Archives and Museum Inc., reports that he attended from 1921-23. E-mail from Jim Savage, March 23, 2015.

3 E-mail from Jim Savage, March 23, 2015.

4 1978 Yankee Scorebook, 39.

5 Ibid.

6 See, for instance, the Rockford Republic, September 22, 1923.

7 Washington Post, October 9, 1924.

8 New York Times, October 17, 1923.

9 New York Times, March 27, 1924.

10 Washington Post, February 21, 1925.

11 Richmond Times Dispatch, December 17, 1928.

12 1978 Yankee Scorebook, 39.

13 Greensboro Record, February 13, 1931. The newspaper reported him as “ill.” His notes provided the National Baseball Hall of Fame indicated he had an operation but did not disclose the reason.

14 New York Times, February 7, 1926.

15 New York Times, February 25, 1926.

16 Richmond Times Dispatch, March 21, 1926.

17 1978 Yankee Scorebook, 39.

18 Richmond Times Dispatch, December 17, 1928.

19 Wagner’s quote appears in the same Boston Herald article, February 27, 1930.

20 Greensboro Record, February 27, 1930.

21 Boston Globe, July 4, 1930.

22 Handwritten note on career stats in his player file in the Hall of Fame.

23 Omaha World Herald, July 26, 1932.

24 Handwritten note on career stats in his player file in the Hall of Fame, and email from grandson Steven Griffin on December 29, 2019.

Full Name

Benjamin Cowan Shields

Born

June 17, 1903 at Huntersville, NC (USA)

Died

January 24, 1982 at Woodruff, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.