Bill Thomas

On the evening of May 4, 1906, right-handed pitcher Bill Thomas appeared in good spirits as he boarded the steamship that would take the Buffalo Bisons ball club on a nighttime passage through the Long Island Sound to New York City. His future remained uncertain, but things were looking up from the previous fall. Then, despite having registered the third of three consecutive 20-victory seasons while pitching in the Pacific Coast League, Thomas had been unconditionally released by the Tacoma Tigers with about a month to go in the 1905 campaign. Over the ensuing winter, he sought to revitalize his career in the East, signing with Buffalo of the highly competitive Eastern League. He had made a successful debut several days earlier, defeating the Baltimore Orioles, and was slated to take the mound in the coming series opener against the Jersey City Skeeters.

On the evening of May 4, 1906, right-handed pitcher Bill Thomas appeared in good spirits as he boarded the steamship that would take the Buffalo Bisons ball club on a nighttime passage through the Long Island Sound to New York City. His future remained uncertain, but things were looking up from the previous fall. Then, despite having registered the third of three consecutive 20-victory seasons while pitching in the Pacific Coast League, Thomas had been unconditionally released by the Tacoma Tigers with about a month to go in the 1905 campaign. Over the ensuing winter, he sought to revitalize his career in the East, signing with Buffalo of the highly competitive Eastern League. He had made a successful debut several days earlier, defeating the Baltimore Orioles, and was slated to take the mound in the coming series opener against the Jersey City Skeeters.

Thomas did not make that start, for somewhere between New London, Connecticut and New York harbor, he mysteriously disappeared from onboard the steamer, never to be seen again. The absence of witnesses reduced club officials and police investigators to speculating that a perhaps seasick Thomas had gone on deck during the ship’s journey, and fallen or was swept overboard to his death in choppy nighttime waters. But Thomas’s body was never recovered, and no official verdict on his demise was ever issued.

William Thomas was born sometime in May 1880 in Florin, California, then a sparsely populated farming community located outside Sacramento. Little biographical data about Thomas — his middle name, parents, schooling, family religion — can be identified with certainty.1 At the time of his disappearance, however, it was reported that Bill had farmed in Florin before entering professional baseball, and that he was the nephew of Sacramento County Sheriff David Reese, a childhood immigrant from Wales.2

Thomas entered baseball consciousness in spring 1903 when he and older brother Ben joined the Sacramento Senators of the Pacific Coast League, a fledgling circuit outside Organized Baseball and a direct competitor of the officially recognized Class A Pacific National League. In short order, Bill Thomas established himself as one of the best pitchers on the West Coast. And as he did so, he received tempting offers to leave the Senators, all of which he declined, much to the applause of a hometown newspaper. “Billy Thomas … has his temptations the same as any other human being,” observed the Sacramento Evening Bee. “But the quiet young man has but one answer for all of them — ‘nit.’3 Thomas figures that he is bound to the local team because of a contract which he has signed and intends to keep. … [By doing so], he deserves the respect of his teammates and of the fans.”4

On May 3, Thomas threw a four-hit shutout at the Oakland Oaks. The 4-0 victory was a remarkable seventh whitewash in his first nine professional starts. In 83 innings, he surrendered just three runs and lost only once, a 2-1 setback in 11 innings to the Los Angeles Angels.5 Although formidably sized (6-feet-4, 180 pounds), the budding star was not a particularly hard thrower. Rather, he relied on a variety of breaking pitches and pinpoint control. By mid-July, Thomas’s 16 wins paced PCL hurlers.6 One of his five defeats, by bad chance, came courtesy of brother Ben. Stationed at an unfamiliar position (third base), the older Thomas’s misplay of a grounder in one inning and his wild throw to first in another cost Bill the two unearned runs that spelled the difference in a 3-2 loss to San Francisco.7

Despite being sidelined by illness for several weeks at mid-season, 23-year-old Bill Thomas turned in an outstanding 29-14 (.674) record for a mediocre Sacramento club that otherwise went 76-89 (.461). Over the grueling 210-game PCL season, he took the mound 47 times, posting an excellent 2.39 ERA in 376 1/3 innings pitched. He also played ten games in the field and chipped in a useful .286 (46-for-161) batting average, with 11 extra-base hits.

With the Pacific National League going under at year’s end, the Pacific Coast League was admitted to Organized Baseball as a Class A circuit for the 1904 season. Sacramento was not going to field a club for the coming campaign, so Thomas signed with recently appointed Tacoma Tigers manager Mike Fisher, his field mentor the season before. The lanky right-hander turned in a yeoman 422 2/3 innings for the Tacoma club, but his 27-24 (.529) record did not match the 130-94 (.580) pace of the pennant-winning Tigers as a whole. Thomas also played 13 games in the outfield and at first base, but his batting, too, tailed off from the previous season: a (46-for-202) .228 BA with only seven extra-base hits. Yet despite the drop-off in Thomas’s numbers, manager Fisher was anxious to have him back and re-signed him for the 1905 Tacoma roster as the Tigers sought to defend the pennant.

Thomas began the new season in sensational style. On May 22, his 3-0 shutout of Los Angeles marked his ninth straight win, against no losses. Tacoma catcher Slats Davis informed gathered sportswriters that “Bill has more to fool a batter with day after day than any man in this league. His almost perfect control enables him to work corners, and keep the ball high or low as he wishes, and when necessary he has the curves to make the batters bite.”8 Three days later, however, the Angels brought the streak to a halt. Behind the one-hit pitching of Spider Baum, Los Angeles sent Thomas down to his first defeat, 6-0.

From that point, the season began to tailspin for both the poorly-drawing Tacoma club and its staff ace. Although the late-August report that “Bill Thomas has not won a game for many a moon”9 was exaggerated, Thomas’s performance slackened noticeably after his blazing start. By mid-season, he had been supplanted as Tacoma’s number one pitcher by Bobby Keefe (30-22). In fact, Thomas was even laid off for several weeks — either (accounts differ) because of a wrist injury or in a club payroll economy move.10 On September 18, he was restored to the active duty roster and snapped a Tacoma losing streak with a 4-2 win over Seattle. In typical fashion, Thomas was touched for 11 hits but spaced them effectively and walked none while striking out two.

With more than a month remaining in the PCL playing schedule and the Tigers headed for a sub-.500 (106-107) finish amid financial difficulty, Thomas was unconditionally released.11 The soft-spoken pitcher reacted philosophically, saying “Fisher thought that I was not doing good work and released me. That’s the privilege of every manager.” Bill then added, “But in my case, I guess I was let go to curb expenses.” Whatever the reason, Thomas expected to be signed by another PCL club shortly.12 Oddly, that did not happen, and he sat at home in Sacramento as the PCL season wrapped up. Although Thomas had been unable to sustain his early season performance, his year-end numbers were respectable: 20-16 (.556) in 38 pitching appearances, with a sparkling 2.06 ERA in 288 innings pitched. Meanwhile, the Tacoma Tigers disbanded after a post-season playoff loss to PCL champion Los Angeles.

Over the winter, Thomas, still only 25 and hopeful of eventually getting a chance in the major leagues, opted for a transcontinental change of scenery. In late January 1906, he signed with the Buffalo Bisons of the Class A Eastern League, a highly regarded circuit just a notch below the majors.13 In reporting the event, the (Portland) Oregonian declared “Bill has pitched great ball … and when he is right is fast enough for any league. He is not a pitcher who uses a world of speed, but has perfect control and can bend them over.”14

On April 30, 1906, Thomas made a successful, albeit shaky, debut for Buffalo. Taking a six-run lead into the ninth inning against the Baltimore Orioles, he weathered a five-run uprising and hung on for a 9-8 win, allowing 13 base hits and an uncharacteristic five walks in the process. But it was a winning effort nonetheless, and with first-game jitters now behind him, Bill was presumably looking forward to his May 5 start in Jersey City.

Between the sets with Baltimore and Jersey City, the Bisons played a three-game series in Providence against the homestanding Grays in which Thomas did not participate. From there, the club’s travel plan was to cover the approximately 185 miles from Providence to Manhattan via a rail-sea transportation route, check into a midtown hotel, and then make the short ferry hop across the Hudson River to play the series opener in Jersey City.

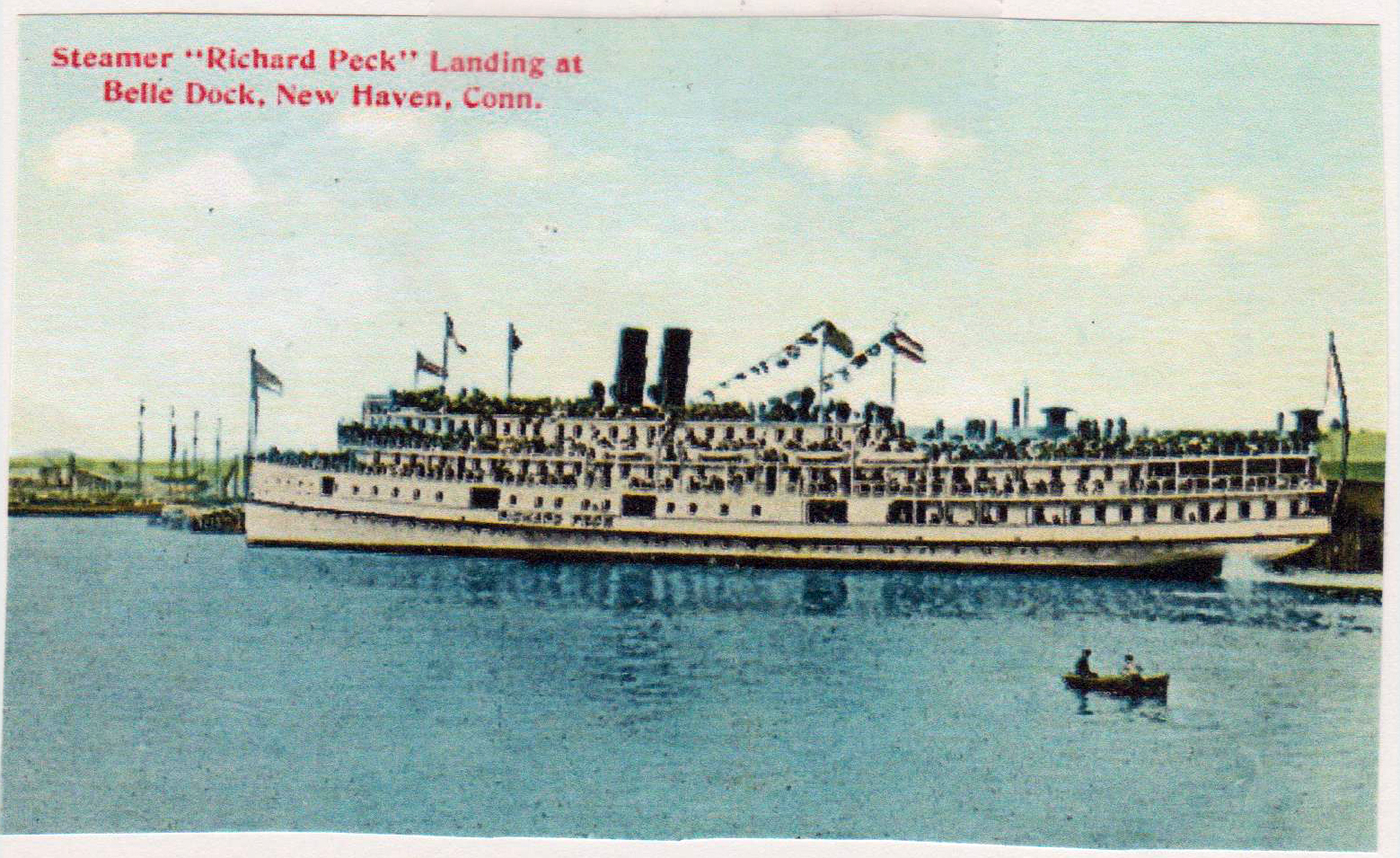

Early in the evening of May 4, 1906, the Buffalo entourage made an uneventful 57-mile railroad trip to New London, Connecticut. There, club members and manager George Stallings boarded the Richard Peck, a spacious 300-foot-long steamship and the pride of the New Haven Line, for an overnight excursion to New York City via the Long Island Sound and the East River.15 Assigned to share a stateroom with Bill Thomas was another Bisons newcomer, pitcher Joe Galaski, a fellow Californian and an acquaintance of Thomas’s from the Pacific Coast League. According to some news accounts, Thomas, fearful of becoming seasick during the trip, took the lower berth in the event that a late-night trip outside the cabin became necessary. Other accounts indicate that Thomas was already feeling woozy as the steamer left port. By all accounts, however, Thomas asked a ship porter to rouse him as the steamer entered New York harbor so that he might take in the sight of lower Manhattan at sunrise.

When Galaski awoke the following morning, he had the stateroom to himself. Thomas’s berth had been slept in, but his cabin-mate was nowhere to be found onboard ship. Galaski, therefore, assumed that Thomas had already gone ashore to do some sightseeing. Curiously, Thomas had left his suitcase behind, so Galaski arranged for its transport to the club’s midtown hotel. But when Thomas did not turn up by late morning, the alarm was sounded. A frantic search by club officials and police found no trace of the missing pitcher at the hotel, onboard the Richard Peck, or anywhere on city streets. An examination of the Thomas suitcase uncovered the expected contents, but the trousers, shirt, and light coat that had been draped over a stateroom chair were unaccounted for. This soon left those concerned with only a shuddering conclusion: that sometime during the night sea passage, Thomas had gotten dressed, stepped outside his cabin, and somehow gone overboard and drowned.

Foul play was not suspected and suicide quickly ruled out. Thomas left behind no suicide note and had not been despondent. To the contrary, the missing man seemed in good spirits the previous evening and was looking forward to his first sojourn in New York City. Thomas’s body was not yet recovered, but death by misadventure was now presumed. Authorities speculated that Thomas had been overcome by seasickness or nausea during the passage and had quietly exited the stateroom to seek relief topside. Perhaps while vomiting over the steamer’s low aft guardrail, he had lost his balance or been swept off the deck by the steamer’s roll through choppy waters and cast overboard. Once that happened and went unnoticed aboard ship, Thomas’s fate was sealed.

The body of Bill Thomas was never recovered, and within days life resumed its normal course for all except a grieving family in California. The Buffalo Bisons doubtless felt the loss of a quiet, affable, and popular teammate and an expected pitching staff mainstay. But even without Thomas, Buffalo was the class of the Eastern League that season, capturing the circuit flag under the leadership of manager Stallings with an 85-55 (.607) record. By that time, the tragedy of the early season was barely a memory, unmentioned in local reportage celebrating the home club’s championship. And so it continues to this day. Well more than a century later, minor league pitching standout Bill Thomas is long forgotten while the precise nature of the events that cost him his life remains a mystery.

Acknowledgments

This bio was originally published in the October 2020 issue of The Inside Game, the quarterly newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee.

This version was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

The sparse biographical information provided above came almost entirely from the contemporaneous newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 The only major leaguer having the same name as our subject was the Bill Thomas who played six games for the 1902 Philadelphia Phillies and was the younger brother of Deadball Era stalwart Roy Thomas. The two Bill Thomases were not related.

2 “William Thomas Meets Sudden Death,” Sacramento Evening Bee, May 8, 1906: 5.

3 Cassell’s Dictionary of Slang shows “nit” in use in the U.S. from the late 19th century to the 1940s as meaning “an emphatic no” (along with “not” or “nix”).

4 “Baseball Gossip,” Sacramento Evening Bee, May 9, 1903: 9.

5 “Sacramento and Butte Divide Honors,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 4, 1903: 4.

6 According to “Fandom Random,” (Portland) Oregon Journal, July, 11, 1903: 19

7 After batting .111 (4-for-36) in 12 games, Ben Thomas was released by Sacramento.

8 “Gossip about the Players,” Seattle Times, May 23, 1905: 11.

9 Seattle Times, August 30, 1905: 10

10 Compare untitled article, Seattle Times, September 6, 1905: 10 (Thomas resting wrist injury) to “Handsome Skel Was Wild,” Seattle Times, September 19, 1905: 11 (Thomas laid off “because he was drawing a good salary while the club was running behind” in billpaying).

11 See “Pitcher Thomas Is Released,” (Portland) Oregonian, October 15, 1905: 17.

12 “Gossip of the Diamond,” Oregonian, October 22, 1905: 17.

13 As reported in the Los Angeles Herald and Oregon Journal, January 28, 1906: 8. According to Baseball-Reference, 16 of the 21 other members of the 1906 Buffalo Bisons played in the major leagues, while Buffalo manager George Stallings’ lengthy resume included field leadership of the 1914 world champion Miracle Boston Braves.

14 “Fresno Is Chosen,” Oregonian, January 28, 1906: 17.

15 The narrative of the fateful voyage has been drawn from contemporaneous reportage published in the Buffalo Courier, Buffalo Enquirer, Buffalo Evening News, Buffalo Morning Times, Jersey (Jersey City) Journal, Pittsburg Press, Providence Evening Bulletin, and Sacramento Evening Bee, May 5-8, 1906.

Full Name

Thomas

Born

May , 1880 at Florin, CA (USA)

Died

May 4, 1906 at , ()

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.