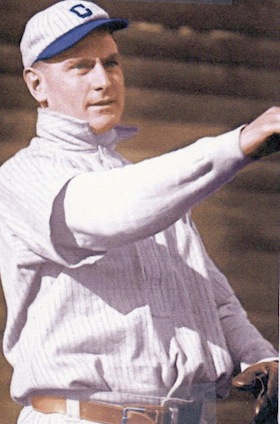

Bob Rhoads

In the midst of the 1908 pennant race, Sporting Life declared that “Robert S. Rhoades of Cleveland is one of the most dependable of modern pitchers. … His habits are good, his conduct exemplary, and in all ways is he a credit to his club and profession.”1 Embodied in this passage are two hallmarks of our subject’s career: (1) a variant, one of many published, of the Rhoads name, and (2) the almost universally favorable treatment that Rhoads received on the sports page. The good press, however, was not undeserved. For most of his eight-season major-league career, Rhoads was a dependable pitcher and occasionally an outstanding one. In 1906 he joined future Hall of Famer Addie Joss and lefty Otto Hess as the first 20-game winners to pitch for a Cleveland club in the American League. Two years later, he contributed 18 victories to a near-miss pennant run. Rhoads was also lively copy, an amiable, witty man whom sportswriters came to rely upon for an anecdote or amusing yarn on slow news days. At times Rhoads himself joined the Fourth Estate, first serving as World Series correspondent for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and decades later becoming a general columnist for a California weekly. In the end, baseball was the centerpiece – but far from the only aspect of – a long and interesting life.

In the midst of the 1908 pennant race, Sporting Life declared that “Robert S. Rhoades of Cleveland is one of the most dependable of modern pitchers. … His habits are good, his conduct exemplary, and in all ways is he a credit to his club and profession.”1 Embodied in this passage are two hallmarks of our subject’s career: (1) a variant, one of many published, of the Rhoads name, and (2) the almost universally favorable treatment that Rhoads received on the sports page. The good press, however, was not undeserved. For most of his eight-season major-league career, Rhoads was a dependable pitcher and occasionally an outstanding one. In 1906 he joined future Hall of Famer Addie Joss and lefty Otto Hess as the first 20-game winners to pitch for a Cleveland club in the American League. Two years later, he contributed 18 victories to a near-miss pennant run. Rhoads was also lively copy, an amiable, witty man whom sportswriters came to rely upon for an anecdote or amusing yarn on slow news days. At times Rhoads himself joined the Fourth Estate, first serving as World Series correspondent for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and decades later becoming a general columnist for a California weekly. In the end, baseball was the centerpiece – but far from the only aspect of – a long and interesting life.

Born on October 4, 1879, in or around Wooster, Ohio, his birth name was Barton Emory Rhoads. During his playing career, he was known by various baseball aliases (Dusty Rhodes, Robert Barton Rhoades, Robert Bruce Rhoades, etc.), but he invariably reverted to his birth name of Barton Emory Rhoads when dealing with census takers, draft-board officials, and other government agents. He was one of at least 12 children born to stonemason Barton George Rhoads (1840-1924) and his wife, Amanda (Horting) Rhoads (1840-1915).2 The Rhoadses were born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, but moved to north central Ohio after the elder Barton’s discharge from the Union Army in 1865.3 Once in their new surrounds, the Rhoadses took up farming. Little is known about young Barton’s early life, but it appears that he completed high school,4 atypical for a late-19th- century farming-family teenager. He began his baseball career as a right-handed pitcher/batter playing on Wooster sandlots and for the local high-school team.5 According to a story passed down to a great-granddaughter, Rhoads’ baseball ambitions were “a disruptive force in the farming life of his Amish parents and their Wooster, Ohio, community” and in 1896 his father “took him to a tryout [with the National League Cleveland Spiders] under duress.”6 But young Barton did not make the club. By 1900, the Rhoads family had moved 40 miles north to Elyria, Ohio, where Barton and his younger brother Edward found work in a steel plant.7

Rhoads first came to public attention in 1900 as Rhodes, pitching for the Spaldings, a fast semipro club in Chicago.8 The following spring, an impressive exhibition-game performance attracted the interest of Charley Frank, the owner-manager of the Memphis Egyptians of the newly formed Southern Association. In March 1901 Rhoads signed with Memphis. Now using the name Bob, but almost invariably called Dusty Rhoades in newsprint,9 Rhoads impressed Association watchers as well, going 22-12 in 37 games for a pennant-contending (75-48) Memphis club.10 That performance did not go unnoticed by major-league teams, with National League Chicago outbidding other suitors for Rhoads’ contract. On April 19, 1902, he made his major-league debut, pitching in relief of Jim Gardner in a 9-5 Chicago victory over Cincinnati. He did not fare as well in his first start, dropping a 7-0 verdict to Pittsburgh. His first win came some three weeks later, a 3-2 decision over Brooklyn. Rhoads then settled into spot-starter/relief duty, going 4-8 in 16 games, with a 3.20 ERA in 118 innings pitched, for the fifth place (68-69) Cubs.

Just prior to the start of the 1903 season, Chicago traded Rhoads to the St. Louis Cardinals for right-hander Bob Wicker. Now pitching for a bad club headed for a last-place (43-94) finish, Rhoads pitched in kind, going 5-8, with an unsightly 4.76 ERA in 129 innings. He drew his release in late August.11 Signed by the Cleveland Naps, he went only 2-3 in five late-season starts, but had now reached the venue where he would achieve his greatest success. In 1904 spring training, Rhoads’ versatility – he was a competent infielder-outfielder and decent batsman, in addition to having pitching talent – was a significant asset in an era of small rosters, and virtually assured him a place on the Naps squad. But it left the Cleveland Leader of two minds. In a March 18 dispatch, an unidentified Leader correspondent marveled at Rhoads’ play at second base.12 Days later, Rhoads’ dalliance at other positions and his seeming disinclination to pitch drew the Leader’s concern.13 That versatility would come in handy during the regular season, when injuries necessitated placing Rhoads in the outfield for five games. For the most part, however, Dusty was a spot starter, alternating the occasional woeful performance (like the July 14 outing in which he and Hess surrendered 21 runs to the New York Highlanders) with the occasional superb one, like the one-hitter he threw against Boston on September 27. Only a two-out single in the ninth by Chick Stahl stymied Rhoads’ no-hit bid. For the 1905 season overall, Rhoads went 10-9, with a much improved 2.87 ERA in 175? innings, for the fourth-place (86-65) Naps.

Rhoads began to blossom in 1905. Although a good-sized man (6-feet-1/172 pounds14), Dusty did not have overpowering stuff. Rather, he pitched to location, relying on excellent control, an assortment of breaking pitches, and a tantalizing slow ball to prevent enemy batsmen from making solid contact. And Rhoads rarely gave in to the hitter, regardless of the count. The Cleveland Plain Dealer later observed that “Dusty is one of those hurlers who have conscientious scruples against cutting the plate at any stage of the game. Consequently, he frequently issues a pass that does not affect the score. He seldom issues a pass that proves costly.”15 As the Naps slid to 76-78, Rhoads went in the opposite direction. He went 16-9, surrendering 219 hits in 235 innings and completed 24 of his 26 starts. He also lowered his ERA to 2.83. The stage was now set for his career year. In the meantime, Sporting Life advised readers how to order cabinet cards for outstanding players, including R.S. Rhoades of Cleveland.16

In 1906 Rhoads posted a 22-10 record, with a sparkling 1.80 ERA. He set career-best marks in wins, winning percentage (.688), starts (34), complete games (31), innings pitched (315), shutouts (7), on-base average against (.227), and strikeouts (a modest 89, while surrendering 92 walks). At season’s end, Rhoads, Joss (21-9), and Hess (20-17) each collected the $500 bonuses promised by club president John Kilfoyl for any Naps pitcher posting a 20-victory season.17 Unhappily for Cleveland, the mound work of its Big Three and the reliably outstanding production of Nap Lajoie (.355 BA, with an AL-leading 214 hits and 48 doubles) were not enough to secure a pennant. A fine 89-64 season record was good only for third place, five games behind the Chicago White Sox of “Hitless Wonders” renown. That offseason, Rhoads, an intelligent, enterprising man, began to expand his employment horizons, acquiring a large wheat farm in Kansas18 and developing soon-to-become-expert skills as a telegrapher.19

The elimination of the 20-win/$500 bonus from Cleveland contracts for 1907 induced a brief preseason holdout by Rhoads and other Naps hurlers, but in Bob’s case, a 15-14 record for the campaign rendered the issue moot. Still, he had pitched well, posting a fine 2.19 ERA for a fourth-place (85-67) Cleveland club. And in 275 innings pitched, he did not surrender a single home run, remarkable even by Deadball Era standards. For the postseason, Rhoads was engaged as a special World Series correspondent by the Cleveland Plain Dealer and regaled readers with lively, opinionated dispatches from Chicago and Detroit.20 Back in Cleveland, however, dissatisfied Naps field leader Lajoie was assaying a roster shakeup, with Rhoads and other veterans reportedly on the trading block.21 Happily for the Cleveland faithful, Rhoads remained with the club and turned in a stellar season for the 90-64 Naps, who finished only a half-game behind Detroit in the final standings. He went 18-12, with a career-best 1.77 ERA in 270 innings pitched, and threw a late-season no-hitter at the Boston Red Sox, winning 2-1. Both Rhoads’ pitching and deportment drew high praise from the baseball weeklies. A glowing page-one profile in Sporting Life declared him “one of the most dependable of modern pitchers. … His habits are good, his conduct exemplary, and in all ways is he a credit to his club and profession.”22 Baseball Magazine was another admirer, describing Bob’s pitching abilities thusly: “Rhoades has speed and splendid command and uses splendid judgment in his delivery of the ball. He is not only immensely popular in Cleveland but in all cities of the American League circuit.”23

Rhoads encored as special World Series correspondent for the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1908, chronicling the Cubs’ second consecutive postseason triumph over Detroit. The paper’s sports page also made good use of Rhoads himself as copy during offseason down time. A March 1909 profile, complete with a photo of a rakishly-dressed Robert Bruce Rhoades, informed readers that he “assays pompadour hair and noisy raiment, but his friends do not hold that against him. … Loaded down with a bobtailed spring overcoat, tan shoes, red socks and a fashionable cigarette, Mr. Rhoades makes a picture for the society page.”24 The piece also reported that “Rhoades is not married. He is one of the few bachelors on the club.”25 This assertion, however, would have come as news to Jenna Whitman Rhoads, the Ohio farmer’s daughter whom Bob had married in 1904. The union, a childless one now shrouded by time, appears unconventional for the era, with the couple frequently living apart before their eventual divorce.26

An unexpectedly poor 1909 season brought the big-league career of Bob Rhoads to an end. His 5-9 record in 20 appearances was emblematic of the decline in the (71-82) Naps fortunes, and at season’s end Rhoads and other Cleveland veterans were placed on waivers. Although he was only 30 years old, no other major-league club sought his services. In February 1910 Cleveland sold Rhoads’ contract to the Kansas City Blues of the minor-league American Association.27 In eight seasons pitching at the game’s highest echelon, Rhoads had posted solid numbers: a 97-82 (.542) record, with 21 shutouts and a 2.61 ERA in 1,691? innings pitched. His modest 522 strikeout total was exceeded by the sum of his walks/hit-batsmen (552), but Rhoads had primarily pitched to contact, holding the opposition to a .256 batting average and rarely surrendering the long ball. All in all, Bob “Dusty” Rhoads had been a reliable middle-of-the-rotation major-league pitcher for almost a decade.

In Kansas City the Rhoads experience replicated his years in Cleveland. He performed stalwartly on the mound and enjoyed favorable coverage on the local sports pages. Hurling for middle-of-the pack Blues teams, Rhoads went 21-15 in 308 innings pitched (1910), 20-16 in 314 innings pitched (1911), and 21-15 in 306 innings pitched (1912) in his first three Kansas City campaigns.28 Rhoads was disappointed when such solid work did not precipitate his recall to the big leagues, but advancing age and a subpar 11-16 season in 1913 worked to foreclose that possibility. Even the Federal League expansion of major-league rosters in 1914 and the installation of a Federal League franchise in Kansas City failed to garner Rhoads a return engagement. Meanwhile, the Kansas City Star continued the tradition of portraying Rhoads as a bachelor bon vivant, dashing about town in his Oldsmobile with comely women by his side and refurbishing his wardrobe with “a new overcoat or scarfpin” about every two weeks.29

Late in the 1913 season, a disastrous relief appearance prompted Kansas City to hand Rhoads his unconditional release.30 That November he signed to pitch the regionally publicized season finale of a San Diego semipro league.31 The following spring, however, Rhoads left the game to devote his time to the management of a motion-picture theater he had purchased in Kansas City.32 Despite the reported financial success of this venture, the restless Rhoads was soon on the move again. In 1918, the now 38-year-old Rhoads informed his World War I draft board that he was a farmer residing in Rialto, California.33 Although still legally married to his first wife, Bob was soon paying court to Alexandra Candlish (née McGowan), a young Canadian widow who served as cook at a nearby ranch. On June 9, 1919, the couple married,34 making Bob the stepfather of Allie’s two children. In time, the birth of son Robert (1922) and daughter Frances (1930) completed their blended family.

For the remainder of his long life, Bob Rhoads engaged in a variety of occupations. Among other things, he worked as a herdsman, a gifted (albeit unlicensed) large-animal veterinarian, a mail-truck driver, and a supply clerk at a military depot.35 In his leisure time, he fished and hunted, coached and umpired in local baseball leagues, and greeted old friends like Ty Cobb and Connie Mack when they visited Rhoads’ adopted hometown of Barstow, California.36 In 1938 Rhoads resumed a prior calling, penning a column called Dustin’ ’Em Off for the weekly Barstow Printer. As blunt and opinionated as decades before, he lambasted the “mechanical smile” flashed by Shirley Temple on a trip through town, and chided a local minister for fire-and-brimstone sermons, observing that “Christianity teaches the joy of living, rather than the fear of death.”37 With son Bob and stepson Harold both in uniform, Rhoads spearheaded community efforts to honor World War II servicemen and worked tirelessly to have their recreational needs filled while on leave.38 Appreciative townspeople later repaid him in kind, raising the funds necessary for Bob to attend a 50th-anniversary celebration of his no-hitter in Cleveland in 1958.39

As he entered old age, increasing deafness and the ravages of chronic tuberculosis took their toll, and Rhoads gradually withdrew from civic affairs. In early 1967 he was admitted to the county hospital in San Bernardino. He died there on February 12, 1967. Barton Emory Rhoads, aka Bob “Dusty” Rhoades, was 87. Following funeral services at a local mortuary, he was buried in Mountain View Memorial Park in Barstow. Survivors included his widow, Allie; children Robert Barton Rhoads and Frances Rhoads Haggin; stepchildren Harold Candlish and Lorraine Candlish Hill; and assorted grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information contained herein include material, including two player questionnaires, contained in the Bob Rhoads file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Retrosheet; family-tree information accessed via Ancestry.com; various of the newspaper articles cited below, particularly the remembrance of Rhoads published in the Barstow (California) Desert Dispatch, February 16, 1967; and “Dusty Rhoads,” an undated reminiscence by great-granddaughter Brett C. Millier contained in the Rhoads file at the Giamatti Research Center. Unless otherwise noted, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, August 1, 1908.

2 Rhoads’ siblings included Catherine (born 1862), John (1863), Monroe Henry (1866), George (1867), Benjamin (1869), Mary Ellen (1871), Sarah (1874), Elizabeth (1877), Edward (1882), Alice (1883), and Susan Ada (1886).

3 Although he was already the father of two infant children, Barton George Rhoads enlisted in a Pennsylvania cavalry regiment in 1863 and served for two years. He later applied for a military pension and evidently took pride in his Civil War service. Co. C, 17th Penn. Vol. Cav. is inscribed on his tombstone in Wooster Cemetery, as per a photo published on the Find A Grave website.

4 As reported in the 1940 US Census. According to the Hall of Fame player questionnaire completed by Rhoads himself, he was a graduate of Wooster High School.

5 As per a Rhoads obituary published in the Boston Record American, February 14, 1967.

6 See “Dusty Rhoads,” an undated published reminiscence by Brett C. Millier, contained in the Rhoads file at the Giamatti Research Center. This story was conveyed to Millier by Rhoads’ son Robert Barton Rhoads, but certain of its details are problematic. Among other things, Barton George Rhoads’ military service is incompatible with his holding Amish scruples.

7 As per the 1900 US Census.

8 See, e.g., the Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1900, June 17, 1900, and July 29, 1900. Subsequently, a factually fanciful profile of Robert Bruce Rhoades maintained that he came to Chicago to live with an older brother. See the Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 7, 1909.

9 Various accounts surfaced regarding his adoption of the first name Bob, later formalized to Robert, or how he came to be called Dusty. See, e.g., Millier, 14: Using Bob, rather than his father’s name, Barton, was designed to preserve the family reputation; Kansas City Star, May 4, 1911: The nickname Dusty was hung on Rhoads by Southern Association fans in Little Rock. The genesis of the universal misspelling of his surname was not discovered by the writer. Suffice it to say that Rhoads’ name was published as Rhoades throughout his playing career and beyond. More than 50 years after he left the game, The Sporting News still captioned Rhoads’ obituary Dusty Rhoades. See The Sporting News, February 25, 1967.

10 Baseball-Reference has no pitching stats for Rhoads in Memphis. The record above was published in the 1902 Reach Guide.

11 As reported in Sporting Life, September 5, 1903.

12 Cleveland Leader, March 18, 1904. Rhoads handled 11 fielding chances flawlessly and turned two double plays in an intrasquad game.

13 Cleveland Leader, March 21, 1904. The Leader correspondent accused Rhoads of loafing in practice and lamented that he “would rather play any other position on the team than pitch.”

14 According to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 17, 1907. Modern baseball reference works uniformly put the broad-shouldered Rhoads’ weight at 215 pounds, the weight provided by Rhoads himself in the late-life questionnaire that he completed for the Hall of Fame Library. But this figure clashes with contemporary references. In addition to the 1907 citation above (172 pounds), see the Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 2, 1909: “Rhoades is heavier than usual, weighing 178 pounds dressed in summer clothing. That brings him down to 170 in primitive dress.” Also noteworthy are the physical characteristics supplied by Rhoads under oath when he registered for military service in 1918 – Height: Tall; Build: Slender (rather than Medium or Stout).

15 Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 11, 1907.

16 See, e.g., Sporting Life, December 5, 1905. What the initial S. stood for is unknown to the writer.

17 As reported in Sporting Life, November 17, 1906.

18 As reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 30, 1907. The year before, Rhoads had made a handsome profit speculating in Kansas City-area farm property, according to Sporting Life, March 6, 1906.

19 As per Sporting Life, April 13, 1907.

20 See, e.g., “How the First Game Looked to ‘Dusty’ Rhoades,” by Robert Rhoades, Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 9, 1907.

21 As reported in Sporting Life, November 30, 1907.

22 Sporting Life, August 1, 1908.

23 Baseball Magazine, Vol. II, No. 2, December 1908.

24 Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 7, 1909.

25 Ibid.

26 The 1910 US and Ohio censuses report Barton Emory Rhoads and wife Jenna living in Townsend, Ohio. When Rhoads registered for military service in 1918, he was living in Rialto, California, and listed Jenna Rhoads of Norwalk, Ohio, as his “nearest relative.” Personal identifiers memorialized in such records establish beyond question that Barton Emory Rhoads and the baseball player variously called Robert Barton Rhoades, Robert Bruce Rhoades, and/or Dusty Rhoades were one and the same person.

27 As reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Kansas City Star, February 18, 1910.

28 Baseball-Reference provides no pitching statistics for Rhoads’ tenure with Kansas City. The records provided above were taken from the annual Reach Guides for 1911, 1912, and 1913.

29 See, e.g., “And They Call Him Dusty: A Fondness for Motoring and Telegraphy, Not to Mention Feminine Company, Divides with Baseball for the Blues’ Twirler’s Attention,” Kansas City Star, May 4, 1911.

30 As reported in the Kansas City Star, September 13, 1913, New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 15, 1913, and elsewhere.

31 See the San Diego Evening Tribune, November 6, 1913.

32 As per the Daily (Springfield) Illinois State Reporter, March 1, 1914, and Duluth (Minnesota) News Tribune, March 7, 1914.

33 As per the draft registration card sworn to and signed in his birth name Barton Emory Rhoads.

34 As per the player questionnaire contained in the Bob Rhoads file at the Giamatti Research Center. Just when Bob and Jenna Whitman Rhoads divorced is unclear. As previously noted, Bob listed Jenna as his “nearest relative” on his 1918 draft registration card, and Jenna Whitman Rhoads is listed as married and living with family in Ohio in the 1920 US Census. Jenna did not report herself as divorced until the next census was taken, 10 years later. She never remarried and died in 1944, age 69.

35 According to a remembrance of Rhoads published in the Barstow (California) Desert Dispatch, February 16, 1967.

36 As recalled by great-granddaughter Brett Millier.

37 Millier, 16.

38 As per the Barstow Desert Dispatch, February 16, 1967.

39 Millier, 16.

Full Name

Barton Emory Rhoads

Born

October 4, 1879 at Wooster, OH (USA)

Died

February 12, 1967 at San Bernardino, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.