Bobby Hogue

Although the vaunted starting duo of John Sain and Warren Spahn is usually credited with leading the Braves to the 1948 National League pennant, stellar relief pitching from several sources also helped Boston to the World Series that fall. One of the men providing this spark was rookie right-hander Bobby Hogue, who baffled NL batters with an array of pitches — and later did the same in the American League while contributing to a Yankees world title three years later.

Although the vaunted starting duo of John Sain and Warren Spahn is usually credited with leading the Braves to the 1948 National League pennant, stellar relief pitching from several sources also helped Boston to the World Series that fall. One of the men providing this spark was rookie right-hander Bobby Hogue, who baffled NL batters with an array of pitches — and later did the same in the American League while contributing to a Yankees world title three years later.

Robert Clinton Hogue was born on April 5, 1921, in Miami, Florida. His father was a well-known boxing trainer, Oakley Hogue, and Bobby himself won 36 of 39 amateur fights while strongly considering a career in the ring. He was also a standout first baseman and outfielder at Miami’s Ponce de Leon High School.

Former Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder (and future Hall of Famer) Max Carey convinced Hogue and his father that Bobby should sign a baseball contract with the unaffiliated Miami club that Carey managed. He did so, and in 1940 posted a record of 8-11 with a 4.15 ERA in the Florida East Coast League. During the offseason, in an “unknown” transaction, Hogue was sent to the Detroit Tigers’ affiliate in the Piedmont League, the Winston-Salem Twins. He pitched two seasons for Winston-Salem, going 9-8 in 1941 (along with a 2.38 ERA) and 17-13 (with a 2.21 ERA) in 1942 — a notable achievement, as he was pitching for a last-place team. In later years, he looked back on this as his best year, since he was with a “hapless tail-ender.” Winston-Salem was also the scene of what Hogue told Complete Baseball was his most embarrassing moment on the field. It came in 1941: “It had rained all morning and muddy Carolina red clay is the slickest stuff in the world. The first man up bunted. I fielded the ball and, honestly, skidded not only off the infield but also into the Asheville dugout. When I finally climbed out, the guy was on third with a triple.”

As with so many young players of the era, Hogue spent 1943-1945 in military service during World War II. Given a fondness for boats, he joined the Navy. An amusing Associated Press story tells of how Detroit GM Jack Zeller sent Hogue his contract for ’43 and was surprised not to be asked for a raise. Hogue wrote back, “The contract arrived and I was delighted with the terms, but I won’t be able to play for the Tigers this year. I’m in the Navy now.”

After three years of service, Hogue hadn’t lost his touch. Detroit optioned him to the Dallas Rebels of the Texas League and he pitched very well in 1946 (9-7, 2.43 ERA after taking a couple of months to get back into form) and ’47 (16-8, 2.31). Control was one of his strengths, and he walked just 59 batters in 222 innings during the latter campaign, when he also beat Beaumont with a 4-0 no-hitter on June 23. Jack Zeller had now become the chief scout for the Boston Braves, and the Braves purchased Hogue’s contract on August 30, 1947 for cash, a player to be named, and options on two other players. Bobby’s ERA had been below 2.50 for three straight years, and Zeller deemed him ready for the big leagues.

The 5-foot-10, 195-pound Hogue was 27 years old when he broke into the majors with the Braves on April 24, 1948, the fourth of seven pitchers to see action in a 16-9 loss to the New York Giants. Hogue’s was one of the best performances of the game at Braves Field, as he yielded just two hits in 3 1/3 innings. A Christian Science Monitor story that spring told of when Braves manager Billy Southworth first met the “portly right-hander” at the minor league meetings the previous December. He asked Hogue, “How are you planning to spend the winter?” When Hogue answered, “On a boat,” Southworth said, “Well, if that’s the case, you better do a lot of brass polishing and deck swabbing to cut down on your weight.” Opening spring training without having seen Hogue again, Southworth declared that Hogue, Jim Prendergast, and Ray Hardee were all “hog fat” and needed to work into form. The manager changed his tune, though, when he found that Hogue was in pretty good shape — and despite having blisters on both feet, asked to get some extra work by pitching to the second squad.

The conditioning and determination paid off; Hogue went 8-2 with two saves and a fine 3.23 ERA (well under the league average of 3.84) during his rookie year. He showed his stuff early on in two games against the powerful Giants, the aforementioned April 24 tilt and a May 1 matchup at the Polo Grounds. In the latter contest starter Bill Voiselle had entered the seventh with a one-hit, 6-0 shutout, then suddenly allowed four runs on three hits; Hogue came in with two outs and the bases loaded, and induced dangerous Walker Cooper to pop out, Still referred to as “the roly-poly right-hander,” Bobby pitched one-hit ball the rest of the way.

This was just a warm-up. While Hogue pitched primarily in relief, appearing in 40 games and finishing 15 (making just one start), he often hurled four or more innings in bailing out faltering mates. On May 28, for instance, after Johnny Sain was shelled against the Dodgers at Braves Field, Hogue came in with two outs in the third and allowed one run the rest of the game. On July 2 at Philadelphia, when Clyde Shoun was ineffective, Bobby entered in the third and pitched two-hit, shutout ball over the final 6 1/3 innings to get the 7-3 win. A week later, when Warren Spahn struggled against the Phillies at Boston, Hogue came to the rescue again with four solid frames in earning the 9-4 victory.

Hogue’s best pitch may have been his slider. “That’s the one I always use in the clutch,” he told the Christian Science Monitor that summer. Years later, fellow hurler Dick Donovan told Arthur Daley of the New York Times that Hogue had as good a slider as he’d ever seen, but that it was “a natural slider and he couldn’t tell anyone how he threw it.” Though Hogue claimed his knuckler was self-taught, he may have owed a great deal of credit to 1948 teammate Nelson Potter, for Hogue said years later that he “stole” his knuckler from Potter, a master of the pitch. This was obviously a man with many pitches, and the 1948 National League Green Book declared that Hogue’s screwball was his best; that he’d learned that one from Frank Shellenback, a minor league pitching great turned big-league coach.

Interestingly, Bobby’s one start of the season came between his two stellar relief jobs of early July, and was a brief one — as he lasted just two innings of a 7-4 victory over the Dodgers on the 8th that was remembered more as the game in which second baseman Eddie Stanky severely sprained his ankle. Once back in the bullpen, however, Hogue returned to form as Boston sought to keep its hold on first place. He had five scoreless innings (with five strikeouts) at Wrigley Field on July 16, and after beating the Cubs with three shutout innings on August 5 was already 7-2 — just one less victory than the 8-7 Spahn. A few weeks later, the Christian Science Monitor noted, “It was reported yesterday that the Braves recently tore up his original 1948 contract and signed him to a new one, naturally at an increase.” Hogue celebrated by pitching shutout ball over the final 4 1/3 innings of an epic 3-2, 14-inning win over the second-place Dodgers in front of 32,499 at Ebbets Field on August 23.

Hogue’s eighth win, which gave Boston a 2 1/2-game lead over St. Louis (with Brooklyn slipping to third) was Hogue’s final decision of the season. Shortly thereafter, the Braves’ two top starters began the run of stellar complete-game outings that led to their “Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain” fame, and Bobby was not needed much down the stretch. He did not, surprisingly, appear in the 1948 World Series against the Indians either, although his teammates acquitted themselves effectively with a 3.37 composite ERA in the six-game Cleveland victory. (The one hurler not to post an ERA of 3.00 or lower in the Series was fellow knuckleballer Nels Potter [8.44 in two appearances].)

In 1949, Hogue worked a bit less — 72 innings in 33 games — but pitched well again, with a 3.13 ERA. He won two and lost two for the fourth-place Braves, again hurling primarily in relief. One concerning stat, however, was that he had lost his edge in strikeout-to-walk ratio (from 43-19 in ’48 to 23-25 in ’49). In 1950, it slipped again — and badly: he walked 31 while striking out only 15, and saw his ERA balloon to 5.03. Hogue won three and lost five in this campaign, and some later articles vaguely mentioned that he suffered an arm injury in ’49. Although it’s not certain, this may have been the cause of his slip in control — and, over time, in effectiveness. Despite some very optimistic press during spring training of 1951, Hogue got off to a disappointing start again with the Braves that year. He pitched just five innings in three appearances, compiling a 5.40 ERA before being placed on waivers. He was claimed by the hapless St. Louis Browns on May 13, at the same time that the Braves purchased right-hander Sid Schacht from the Browns. Not long after that, on July 31, the Yankees purchased Hogue’s contract at the same time as they bought the rights to Cliff Mapes from St. Louis; the two transactions were part of a cluster of deals involving a number of players. Hogue was sent outright to New York’s American Association team in Kansas City, where he appeared in seven games and went 4-0 in 22 innings. On August 20, the Yanks called up two players from the Kansas City Blues, Hogue and a youngster named Mickey Mantle.

As he had in ’48, Hogue came up big in a pennant race. The now 30-year-old pitcher was praised by New York manager Casey Stengel and coach Jim Turner for his solid relief work, although Complete Baseball’s Ben Epstein termed him a “fat man with a knuckler” and a “misfit” who threw to the “odd anatomy and thick mitt of backstop” Yogi Berra. Hogue surprised everyone by throwing a total of 10 innings of relief down the stretch without yielding a single run. His contributions included 7 1/3 innings during three key games in the midst of the Yankees’ red-hot pennant fight with Cleveland, and 2 2/3 innings of shutout middle relief in two World Series appearances against the Giants. Thanks to his help, the Yanks won the Subway Series in six games for their third straight world championship.

The stout Hogue developed his knuckler out of “sheer necessity,” he told Epstein. “I knew it was either rassling, raking leaves or some other business if I didn’t add something to my alleged fastball and curve,” he said with a grin. “So I just stuck to the standard pitches and adopted the knuckler.” Playing around with it for a couple of years, using it as perhaps his third or fourth pitch in 1951, he had a 6-0 record between Kansas City and New York. After two wins and five saves with the Yankees that year, it wasn’t until the next spring that Hogue suffered his first New York loss, on May 24, 1952, against the Red Sox in Boston.

Hogue was a solid hitter, and one writer once made the humorous discovery that he had topped three leagues in hitting. This is rather deceiving — he led the American League with a 1.000 batting average in going 2-for-2 with the Browns; led the National League at .500 (2-for-4) with the Braves; and headed the American Association at .600 (6-for-10) with the Blues — but he did bat .233 lifetime in 172 at-bats in the majors, a high mark for a pitcher. He was also a good fielder who didn’t make an error in major-league ball until his final season. Not bad for a guy the press called “chunky” throughout his career.

In 1952, however, Hogue’s up-and-down stretch in the majors took a final downward turn. He appeared in 27 games with the Yankees, and while he did notch four saves, his 3-5 record and 5.32 ERA prompted the club to place him on waivers in early August. He was claimed again by the Browns, on August 4; moving from the AL penthouse to the outhouse, he threw 16 1/3 innings and recorded a record of 0-1 with a very stingy 2.76 ERA for seventh-place St. Louis. It wasn’t enough to save his job. On September 27, 1952, Hogue appeared in relief at Comiskey Park in Chicago, giving up one hit and no runs to the White Sox in the last two innings he pitched in the major leagues.

Back to the minors in 1953, Hogue pitched 135 innings for the Toronto Maple Leafs of the Triple A International League, finishing with a record of 8-11 and a 3.60 ERA. He got into just one game in 1954 for Toronto, walking two and giving up three hits as he was touched for five runs (three earned) in zero official innings of work. From here he went on the voluntarily retired list, and then was given his release on August 5.

There was one more try the following year, but Hogue’s pro career finally petered out with 33 innings of American Association work for Minneapolis in 1955 (4.64 ERA with a 1-0 record) and five innings for the independent Williston team in the Manitoba-Dakota League. He was still just 34, but it was time to hang up his spikes.

After baseball, Hogue lived in the Florida Keys and continued to enjoy fishing for pleasure. He worked for the Miami News for three years and then in the circulation department of the Miami Herald for many years, retiring in 1986. Robert Clinton Hogue died on December 22, 1987, in Miami at the age of 66 after a long battle with cancer. He just missed the 40th reunion of the 1948 National League champions in Boston the next summer, but even if his name is largely forgotten by casual baseball fans today, those who watched or played with the Braves in ’48 knew full well his value to the club.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Epstein, Ben. “Knuckle Ball Bob,” Complete Baseball, September 1952

1948 National League Green Book.

Christian Science Monitor, New York Times

Thanks to Davis O. Barker and Bob Brady.

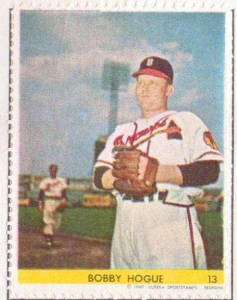

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Robert Clinton Hogue

Born

April 5, 1921 at Miami, FL (USA)

Died

December 22, 1987 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.