Brother Matthias: Martin Leo Boutlier

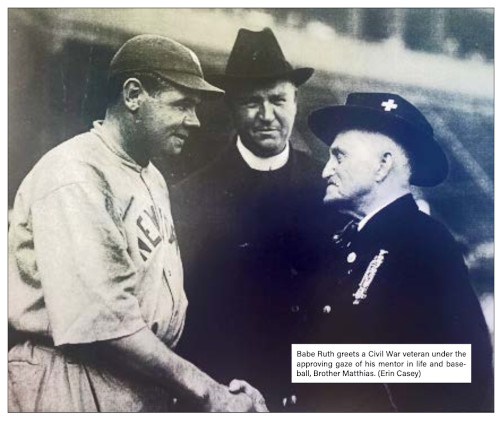

Babe Ruth greets a Civil War veteran under the approving gaze of his mentor in life and baseball, Brother Matthias. (Erin Casey)

Shortly before he died, baseball superstar Babe Ruth publicly credited a man who was born on Cape Breton Island with making him the ballplayer and man he had become. He did it in writing. Not once, but twice. In his 1948 autobiography, the third and final telling of his life story, George Herman Ruth was effusive about Martin Leo Boutilier, a man who taught him at St. Mary’s Industrial Training School in Baltimore. “It was at St. Mary’s that I met and learned to love the greatest man I’ve ever known,” Ruth said of the teacher he knew as Brother Matthias. “He was the father I needed.”1 Ruth admitted he’d been a “bad kid,” listed as incorrigible, when he was sent to the reform school and orphanage just west of Baltimore at the age of 7.

On the same day Ruth died, his second tribute to Matthias appeared in an inspirational publication called Guideposts Magazine, founded by Christian preacher Norman Vincent Peale, author of the best-selling book The Power of Positive Thinking. In the Guideposts article attributed to Ruth, billed as his “last message,” he repeated that he had been “a bad kid,” and that Matthias had turned his life around and had introduced him to baseball. He called the 6-foot-6 Nova Scotian “the greatest man I have ever known.” Ruth said Matthias detected natural talent in the troubled boy, and taught him how to throw, catch, and hit properly. “I would watch him bug-eyed,” Ruth said of seeing his mentor drive a ball 350 feet with a bat in his right hand in the St. Mary’s schoolyard.2

Ironically, although Ruth himself credited Matthias with making him a ballplayer, the press acclaimed another Catholic brother for discovering and coaching the baseball phenom and getting him into professional baseball. And like many things in baseball, the true story was eclipsed by another that became embedded in the lore of the sport. Consequently, the story of the quiet Canadian, Brother Matthias, and his contribution to baseball history are not well known, and deserves to be shared.

Martin Leo Boutilier was born in 1872 in the coal-mining community of Lingan, near the tip of Cape Breton Island, not far from New Waterford, the eighth of 10 children born to Joseph Boutilier and Mary Ann Howley. Two of their sons had died as infants. Joseph Boutilier, variously listed as an engineer or machinist, maintained and repaired equipment in the mine at Lingan, and on seagoing vessels. Because of difficult economic conditions in the Maritimes, some other members of the Boutilier family had moved to Boston. As the mine in Lingan began to play out, Joseph began to explore employment options elsewhere because he had so many mouths to feed. He first tried Halifax, a bustling seaport of 68,000, but by the late 1870s a lingering recession limited prospects there, so he took his family farther south to Boston, a city of 362,839, late in 1880.3 The family settled in East Boston, not far from today’s Logan Airport, where many expatriate Canadians had taken up residence. Son Martin had just turned 9 years of age.

The Boutilier family settled into a city that was crazy about baseball. They may have been familiar with the game back in Lingan, but it’s doubtful they had much exposure to it in the hardscrabble mining community where spare time was rare. With seven boys ranging in age from 6 to 22, the family had nearly enough to field their own team in their new home. Residents of East Boston had been playing the game since as early as 1843, and immigrants considered it an important part of becoming American. The streets of working-class Boston were often filled with men and children playing games to the delight of spectators who cheered them on from front porches and windows. The Boston Red Stockings were charter members of the first professional baseball league, the National Association, founded in 1871; they placed second that first season and were league champions from 1872 to 1875. Boston was a strong franchise and became a founding member of the National League in 1876, capturing the pennant of the new league in 1877, 1878, and 1883. It was clear baseball had a firm grip on America’s fifth largest city.

Aside from their love of baseball in their adopted city, Martin and his older brother Thomas were more spiritually inclined than other members of their family. Thomas was attracted to the Brothers of Charity, a Belgium-based Catholic order that operated the House of the Guardian Angel, an orphanage and training school, in Boston. Thomas was sent for training at the Brothers of Charity in Montréal, but his inability to speak French proved to be an obstacle and he returned to Boston.4

Back home, Thomas connected with the Congregation of the Brothers of St. Francis Xavier (known as the Xaverians), another Belgium-based order that had its American headquarters in Louisville, Kentucky, and whose operating language was English. The Xaverians (pronounced za-VAIR-ians) focused their work on education and moral guidance for youth. They are laymen who take the same vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity as priests, but cannot conduct Mass or bestow sacramental privileges. Thomas Boutilier discovered that during his sojourn in Canada, younger brother Martin had become involved with the Xaverians in about 1890.

The Xaverians had begun operating a new school in East Boston where Martin likely first encountered them. By 1891, he signed an “agreement of membership” and became an apprentice with the order. By the time his training was completed four years later, he had been assigned the name Brother Matthias, as was the custom of the Xaverians. Thomas also joined the order and became Brother Amandus. During their training, the Boutilier brothers were sent to Xaverian-operated Catholic schools in Baltimore – Amandus to Mount St. Joseph College and Matthias to St. Mary’s Industrial Training School.5 The schools were not far from each other, but Mount St. Joseph was a more traditional high school with tuition and board and a focus on academics, while boys at St. Mary’s were often sent there by the courts, were known as “inmates” and were trained to work in the trades. St. Mary’s was a combination training school, orphanage, and detention facility for which permission was required to leave the premises.

Brother Matthias was better educated than his older brother and took up teaching at St. Mary’s, while Amandus performed administrative duties at Mount St. Joseph. Somewhere along the line in Xaverian paperwork, an “i” was dropped from the spelling of the Boutilier name to become Boutlier. Matthias, likely because of his size, became head disciplinarian at St. Mary’s, which sometimes housed as many as 800 boys. He could bring order to an unruly scene simply by showing up and quietly making his presence known. To his colleagues, he was known as Big Matt, but to the boys, he was known as The Boss. Matthias was also one of the baseball coaches at the school, which sometimes fielded 40 or more teams in a season. Baseball was king at St. Mary’s, which had two fields, one for the older boys and another for the younger ones. It was to St. Mary’s that a youngster would come, just as Matthias was settling into a life in the service of God. The boy changed the life of the big Xaverian who saw something special in him, trained him in the finer points of baseball, and helped him transform the game.

George Herman Ruth was born in Baltimore on February 6, 1895, in the Ridgely’s Delight neighborhood, immediately west of Camden Yards. He was the first child born to George and Katie Ruth, who had eight children, but only George Jr. and his sister Mary survived past infancy. George Sr. and his brother John operated a lightning-rod business established by their father, but in 1901 George left the business to operate a bar downtown on West Camden Street, and his family moved in above it. The premises were in a gritty working-class area, and young George soon found himself getting into trouble while his parents worked long hours in their saloon. Strains became evident in their marriage, aggravated by too much alcohol consumption. Meanwhile, George Jr. was becoming a street kid, tossing stolen eggs and tomatoes at the heavy vehicles on their way to and from the Baltimore docks. A lefty, young Ruth developed an accurate arm and also joined his pals in rudimentary games of baseball on the busy city streets. Sometimes Ruth and his fellow troublemakers were caught and whipped for their misdeeds by truck drivers, and they received beatings from shopkeepers, he recalled in a 1928 autobiography, ghost-written by sportswriter Ford Frick.6

In 1902 George Ruth, at the urging of a police officer friend, placed his 7-year-old son at St. Mary’s Industrial Training School, to which courts sent many youngsters in a bid to deter them from a life of crime. “I was listed as an incorrigible, and I guess I was,” Ruth admitted in his 1948 autobiography.7 Not long afterward, either in the classroom or on the ball field, the youngster met Matthias, the man who became a surrogate father of sorts. In the classroom, Matthias encouraged the young lefty to write with his right hand, in flowing script. On the ball field, Matthias noticed abundant raw talent and took extra time with the newcomer, drilling him in proper fielding and hitting techniques. Ruth became a catcher, but the school had no gloves suitable for lefties, so he was forced to catch with a glove on his left hand, then quickly flip off the glove and throw the ball with the same hand. It was cumbersome, but young Ruth became adept at it. And when he ridiculed a pitcher he was catching one day, coach Matthias made him take over the pitching duties himself. It was a fateful move that soon began attracting attention to the young hurler. Ruth played on school teams with older boys, winning the school championship in 1912. During his nearly 12 years at the school, Ruth off the field became a skilled shirt-maker in the school’s tailoring shop, which also made uniforms for the St. Mary’s baseball teams.

Baseball and young George Ruth were meant for each other. And Brother Matthias cultivated and channeled the raw talent of the loudmouthed, good-natured kid to whom he took a shine. One of Ruth’s pals, Fats Leisman, figured Ruth was a baseball prodigy who didn’t really need much direction. “My personal opinion is that the Babe was born to play ball,” Leisman later wrote.8 For his part, Ruth disagreed. He said this about his mentor and coach:

Brother Matthias had the right idea about training a baseball club. He made every boy on the team play every position in the game, including the bench. A kid might pitch a game one day and find himself behind the bat the next or perhaps out in the sun-field. You see Brother Matthias idea was to fit a boy to jump in in any emergency and make good. So whatever I have at the bat or on the mound or in the outfield or even on the bases, I owe directly to Brother Matthias.9

Ruth was in awe of Brother Matthias and copied many of his techniques. The big man swung with an uppercut at a time when level swings were in vogue to smash line drives during the Deadball Era. But Matthias could easily loft a ball over the outfield fence with his powerful swing. His young protégé developed his own long swing and powerful uppercut. Matthias, a big man, ran around the bases with surprisingly small steps and was rather pigeon-toed. There is no shortage of film showing Ruth scampering around the bases with similar footwork during his long career. The form of Matthias was unorthodox, but effective. By copying much of what he saw in Matthias, young Ruth went on to revolutionize the game of baseball, especially with his bat. “I think I was born as a hitter the first day I ever saw him hit a baseball,” the home-run king said of Matthias in his 1948 autobiography.10

Ruth’s baseball exploits, particularly the effectiveness of his pitching, began attracting attention in the Baltimore baseball community during his years at St. Mary’s. In his annual report for 1913, Brother Paul, the school superintendent, proudly reported: “One boy created a sensation by his excellent work.”11 He wasn’t talking about academics. The boy was Ruth; the “work” was baseball. A player at Mount St. Joseph, which fielded highly competitive teams, was among those who took note. He suggested to Brother Gilbert, his ball coach and an administrator at the school, that he see the young hurler for St. Mary’s. Gilbert did so, and was impressed with what he saw. Gilbert, an extrovert, unlike the retiring and rather shy Matthias, had many connections in the baseball community, and was friends with Jack Dunn, owner of the Baltimore Orioles of the Eastern and then International Leagues. Gilbert often alerted Dunn to local talent, and Dunn, a former major-league pitcher, was always on the lookout for young pitchers he could develop.

There are several versions of the story about how Dunn learned about Ruth, most involving a tip or introduction by Brother Gilbert. In his 1948 autobiography, Ruth said that during February of 1914, shortly after his 19th birthday, he was throwing a baseball around the still-frozen yard at St. Mary’s, when he was approached by Brothers Matthias, Gilbert, and Paul, and the Orioles owner. Gilbert introduced him to Dunn, who asked the startled Ruth if he’d like to sign with the Orioles.12 Dunn offered to become his legal guardian and pay him $600 for the 1914 season. Babe accepted.

Brother Gilbert had many friends among sportswriters, some of whom promulgated the story that Gilbert not only tipped Dunn to Ruth, but that he had also coached him. In a seven-part series in the Boston Globe published in 1923, in which Brother Matthias is barely mentioned, Gilbert’s credentials were described this way by the editors: “No other one man, except the Babe himself, knows more about his life than does Brother Gilbert.”13 Gilbert was soon enshrined by sportswriters as the discoverer of Ruth. For his part, the modest Matthias made no protest. He and his surrogate son knew the truth, and felt there was no need to upset Gilbert’s applecart. Gilbert, a popular after-dinner speaker, delivered more than 1,000 speeches in his lifetime, many of them discussing his time with Babe Ruth. When he died in 1947, Gilbert was working on his memoirs in which Ruth loomed large. At the time, sportswriters were still hailing him as the one responsible for The Babe.

George Herman Ruth Jr., now 19, was quickly dubbed “Babe” when he appeared at spring-training camp for the Orioles in Fayetteville, North Carolina. “Look at Dunnie and his new babe,” one of the older players said at one point, while another took pity on him when Dunn bawled him out for something, saying: “You’re just a Babe in the woods.”14 Another story was that Dunn was impressed with a home run Ruth belted at Fayetteville and reportedly said: “This baby will not get away from me.”15 The name stuck. To Matthias, however, he was always “George.”

Babe Ruth did well with the Orioles, but Jack Dunn faced unexpected competition in 1914 from the Baltimore Terrapins of the new Federal League, and was strapped for money. In July he sold his “baby” to the Boston Red Sox along with two other players. Babe would earn $650 a month in Boston, up from $500 in Baltimore. As a tailor, for which he’d been trained at St. Mary’s, he would have earned about $60 a month. Ruth was unhappy, however, at leaving Baltimore, his home, and Brothers Matthias, Paul, Gilbert, and others. Fortified with the acquisitions from Dunn in Baltimore, the Red Sox were making a run for the American League pennant; by August, however, the Philadelphia Athletics had an insurmountable lead, and Boston owner J.J. Lannin decided to send Ruth down to the Providence Grays of the International League for more playing time and experience. The Grays, purchased by the Canadian-born Lannin from the Detroit Tigers, were a sort of farm team for the Red Sox. Babe retained his Red Sox salary but was unhappy at the move, which he viewed as a demotion. He was in Providence for six weeks, helping the team to the International League pennant. Along the way, he belted his first home run in a professional game, on September 5 in Toronto against the Maple Leafs. Mythmakers insist the ball sailed over the bleachers at Maple Leaf Park on Hanlan’s Point island into Lake Ontario, but contemporaneous press accounts made no such claim of the ball getting wet that day.16

Babe returned to Boston and helped the Red Sox win three World Series in the next four years. In 1920 he was famously sold to the New York Yankees. There, he quit pitching so that he could wield his mighty bat in every game. He stayed in touch with Brother Matthias and St. Mary’s, and often brought fellow players with him when he returned to the school for visits. In 1919 a fire heavily damaged St. Mary’s, and Babe pitched in to help fundraising efforts, persuading the Yankees to let the St. Mary’s band accompany the team on a road trip, and to pass the hat to rebuild the school that Babe considered his real home.17 As his fame grew and he transformed the game with his home runs and made the Yankees a formidable powerhouse, Babe continued to stay in contact with Brother Matthias, and sent him tickets for some games. Babe’s late-night extracurricular activities with drink and the ladies often got Ruth into trouble with team brass, who occasionally called upon Matthias to counsel their star.

Matthias visited New York to see Babe play in 1922 or 1923, and was surprised when Ruth announced that he was buying Matthias a brand-new Cadillac as a thank-you for everything he had done.18 The big brother was astounded at Babe’s generosity. Because of his vow of poverty, Matthias had the luxury car registered in the name of St. Mary’s, which gave him exclusive use of it. Always the teacher, Matthias used it as an educational tool at times, showing the boys rudimentary auto mechanics. He also ferried around young passengers to various concerts and other events. One night during the summer of 1927, while returning home from an out-of-town event, the Cadillac stalled on some railway tracks and was demolished when struck by a train.19 Luckily, Matthias and the boys escaped unscathed. When Babe heard about the incident, he promptly bought Matthias another Cadillac.20

By 1926 Babe was constantly womanizing and had separated from his first wife, Helen. He considered divorce, but Matthias talked him out of it. Ruth recorded 47 home runs that year, bouncing back after a poor 1925 season, but his off-field activities produced grief for Yankees general manager Ed Barrow and on-field manager Miller Huggins. The team assigned a private eye to follow their star, whose late-night antics continued unabated. In June the Yankees made a road trip that included Chicago, a city whose delights Babe always sampled in large dollops. Team management called upon Brother Matthias to come to Chicago and speak to Ruth about their star’s behavior, hoping the Xaverian could yet again provide fatherly advice and modify Ruth’s behavior.

The city was hopping when the Yankees arrived in town. The 28th International Eucharistic Congress was being held for Catholics around the world, the first time the event had been held in the United States. The Yankees found an invitation for Matthias to attend the congress, and asked him to speak to Babe while both were in town. One evening Matthias came to the Prado Hotel, where the Yankees were staying, and occupied a chair in the hotel lobby from which he could watch the elevator. Ruth soon appeared, apparently ready for a wild night on the town, but he spotted Matthias and the two men greeted each other warmly. Matthias said he was in town for the religious congress and to see Ruth play the White Sox. He said he wanted to take his former pupil out to dinner and to chat. His plans for the night dashed, Ruth agreed and the pair stayed out until 11 p.m. as Matthias sternly advised Ruth to clean up his act because many people were concerned for him. He likely reminded the Babe that he had been encouraged to live a God-centered life as a young man at St. Mary’s, not a hedonistic lifestyle filled with women and booze. What kind of role model was George for young men like those still at St. Mary’s? Babe was letting down the boys at his old school who idolized him. The sobering talk left the prodigal son promising to do better. Ruth biographer Marshall Smelser called this a “turning point” in Ruth’s behavior. “Certainly he no longer after that time had the reputation for hell-raising that he had before.”21

It was in that second Cadillac that Matthias himself got into trouble. He was seen driving the big car while repeatedly visiting a much younger woman during 1931, and concerned neighbors reported him to the Catholic Archdiocese of Baltimore. Matthias was 58 at the time, the woman 23. He denied any improper relationship when his activities were investigated by church officials. Matthias could have been expelled from the Xaverians for violating his oath of chastity, leaving him penniless as he approached the age of 60. Instead, the church reprimanded him and transferred Matthias to a Xaverian-operated school in Danvers, Massachusetts, noting: “If Brother Matthias had been more amenable to discipline over a period of years, his scandalous actions might have been avoided.”22 He’d been head disciplinarian at St. Mary’s, yet his own conduct had fallen short of what was expected of him. In 1942 he celebrated 50 years with the Xaverian order while living in retirement at St. Joseph’s Juniorate in Peabody, Massachusetts. Two years later, Matthias was found dead in his room at the age of 70. He is buried at the Xaverian cemetery in Danvers. It is not known how much he was able to see his surrogate son after his move to Massachusetts.

In his only known interview with the press, the unheralded Matthias told a reporter in 1935 that Babe was one of a kind: “There never was a better boy at St. Mary’s School in Baltimore than ‘George.’ I was there 38 years and there were better ball players, but never a better boy.”23 The affection of the surrogate father was clear. And Babe returned the sentiments publicly in print shortly before his own death in 1948.

Sources

The author has also written a full book on Brother Matthias. See Brian Martin, The Man Who Made Babe Ruth: Brother Matthias of St. Mary’s School (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2020).

Notes

1 Babe Ruth, as told to Bob Considine, The Babe Ruth Story (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1948), 13, 18.

2 Babe Ruth, “The Kids Can’t Take It if We Don’t Give It!,” Guideposts Magazine, October 1948: 1-2, 23-24, accessed February 10, 2018, http://baberuthcentral.com/remembering-the-babe-/babe-ruths-public-statement.

3 The move of the Boutilier family to Halifax was recorded by Cape Breton researcher Virginia MacDonald in the November 24, 2007, edition of the Cape Breton Post. Her grandfather was born in Lingan in 1871 and her father, Bernard, was a machinist/engineer. The 1881 Census of Canada recorded the Boutiliers as still living in Lingan. Descendants of the Cape Breton Boutiliers, Jean Mor and Francis McGillivary, confirmed to the author that the move to Halifax came about this time.

4 Brother Amandus Dossier CCFX, 6/03 #318, of the Xaverian Brothers, University of Notre Dame Archives, South Bend, Indiana.

5 Brother Matthias Dossier, CCFX 6/04 #329, of the Xaverian Brothers, University of Notre Dame Archives, South Bend, Indiana.

6 Babe Ruth, Babe Ruth’s Own Book of Baseball (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1928), 3-4.

7 Babe Ruth, to Considine, The Babe Ruth Story, 12.

8 Lou Leisman, I Was with Babe Ruth at St. Mary’s (Aberdeen, Maryland: self-published, 1956), 21.

9 Babe Ruth, Playing the Game: My Early Years in Baseball (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2011), 6.

10 Babe Ruth, The Babe Ruth Story, 15.

11 Marshall Smelser, The Life That Ruth Built: A Biography (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1975), 31.

12 Babe Ruth, The Babe Ruth Story, 20.

13 Brother Gilbert, C.F.X., “Babe Ruth’s Great First Home Run – Brother Gilbert Discovers Him,” Boston Sunday Globe, October 14, 1928: 20.

14 Babe Ruth, The Babe Ruth Story, 25-26.

15 “Babe Ruth ‘A Natural’ Even as Oriole Rookie,” Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1948: 15.

16 Leonard Levin, “Baseball. Arrival of Ruth Turned Grays’ Skies to Blue/81 Years Ago, the Bambino Led Providence to the International League Pennant,” Providence Journal, August 14, 1995: B4. Levin quotes from Journal sportswriter Bill Perrin, who wrote about Ruth’s blast that sailed “over the right field fence.” No Toronto paper reported that the ball made it into the lake that day.

17 Babe Ruth, The Babe Ruth Story, 132.

18 Some reports say the year was 1925 or 1926, but an early 1924 report in the Baltimore Sun mentions Matthias taking St. Mary’s boys to a theatrical performance “in an automobile given the latter by ‘Babe’ Ruth, the baseball player.” Date of the article is March 17, 1924, “White House Talk Explained by Lang,” on page 4.

19 “Auto Presented by Babe Ruth to St. Mary’s Smashed by Train,” Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1927: 22.

20 Babe Ruth, The Babe Ruth Story, 107.

21 Smelser, 239.

22 Matthias Dossier, University of Notre Dame Archives.

23 Thomas Sheehan, “Brother Matthias Talks of ‘George,’” Boston Evening Transcript, February 28, 1935: 6.

Full Name

Martin Leo Boutlier

Born

July 11, 1872 at Lingan, Nova Scotia (Canada)

Died

October 16, 1944 at Peabody, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.