Bud Beasley

Bud Beasley Elementary School in Sparks, Nevada, opened in the fall of 1995. It was named for Arvel Lewis “Bud” Beasley, who served northern Nevada for more than 60 years as a schoolteacher and athletic coach. From 1944-54 he was also a minor-league pitcher, a colorful left-hander who delighted fans with his antics. Southpaws have a reputation for zaniness. Beasley joked that he was baseball’s most left-handed pitcher.1

Bud Beasley Elementary School in Sparks, Nevada, opened in the fall of 1995. It was named for Arvel Lewis “Bud” Beasley, who served northern Nevada for more than 60 years as a schoolteacher and athletic coach. From 1944-54 he was also a minor-league pitcher, a colorful left-hander who delighted fans with his antics. Southpaws have a reputation for zaniness. Beasley joked that he was baseball’s most left-handed pitcher.1

He was born to Corrydon and Sophie Beasley on December 8, 1909, in Melrose, New Mexico Territory. He had an older brother, Orel, and a younger sister, Lorene. The family moved to Iowa Park, Texas, about 1912, and then to Santa Cruz, California, in 1920. Corrydon operated a confectionery in these towns.2

Bud excelled in baseball, football, and basketball at Santa Cruz High School, graduating in 1929. He received a football scholarship to attend the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR) where he played on the varsity team for four years as a halfback and quarterback. He graduated from UNR in 1934 with a bachelor’s degree in history. He later did graduate work at UNR, Columbia and Stanford Universities, and the University of Washington, earning two master’s degrees.

From 1936-74, Beasley taught history and physical education at Reno High School and coached the school’s baseball, football, and basketball teams. And from 1934-43, he pitched for semipro teams in the Reno area. He met his future wife, Nellie Meyers Esterbrook, in 1939 when he coached her women’s softball team; they married two years later. An outstanding bowler who competed in national tournaments, Nellie was inducted into the National Women’s Bowling Association Hall of Fame in 2002.3

With a shortage of eligible players during World War II, the St. Louis Cardinals signed Beasley to a contract in 1944 and assigned him to the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League. Beasley stood 5’8” and weighed 170 pounds. The jovial pitcher resembled Popeye, with a large nose and protruding chin. He threw a fastball, curveball, and changeup, and a knuckleball that moved “like a snake on a red hot stove.” His age seemed a mystery. He was in fact 34 years old when he was signed, although the Cardinals may have thought him only 30. Beasley made clear that his teaching career came first, meaning that he could join the Solons only after the school year ended in June and would leave the team in September at the beginning of the next school year.4

In 1944 Beasley compiled a 5-6 record for the Solons. The highlight of his season came in Seattle on September 2, when he pitched a completed 17-inning game allowing only eight hits in a 5-4 Sacramento victory. Though not known for his hitting, that day he got four hits, and in the final inning he doubled and scored the go-ahead run. The next season he led the PCL in winning percentage with a 12-4 record and became a popular drawing card, combining “comedy with talent.”5

To disrupt the batter’s timing, Beasley fashioned windups that were comically exaggerated and intentionally unpredictable, varying in style, speed and duration. Sportswriters, such as Jack Hewins of the Reno paper, struggled to describe them: “He started his wiggle-waggle windup down around his shoelaces, worked up to his knees, waved the ball at centerfield, third base and the blonde in the fourth row. Then he threw it. By that time the batter had the flibberty jibbets and the rival manager had galloping squawkitis.”6

The rules required the pitcher to deliver the ball within 20 seconds. Sometimes Beasley quick pitched it to catch the batter off guard; other times he made the batter wait 19 seconds. “When the fans think I’m clowning around out there, I’m really practicing applied psychology on the batter,” said Beasley, who studied psychology but also liked to have fun.7

In a key moment against Portland in 1945, with the bases loaded and the dangerous Spencer Harris at the plate, Beasley forced Harris to endure several delays before retiring him.

He “changed balls five times, weighed them several times by juggling one in each hand, intermittently tied each shoestring, conferred with his catcher three times, and strolled over to the dugout for a drink once. Before the final pitch, he walked to the plate and borrowed Harris’ bat to knock the dirt from the cleats of his shoes.” He had pulled the latter stunt before. In the 1945 PCL All-Star Game, Red Adams stepped to the plate to face Beasley, who then borrowed Adams’s bat to knock the mud from his cleats. But he accidentally broke the bat, and he handed only about a foot of the original lumber back to Adams.8

Beasley’s sense of humor rarely played hooky. He told the story of a game in which he was getting hammered. “I was pitching in Hollywood and everything they were hitting was falling in. I took my glove and threw it to the umpire behind second base. I said, ‘You better shag some of these or we’ll be out here all night.’ He put it on and said, ‘Let’s go.’”9

Casey Stengel managed the Oakland Oaks in 1946, and when Beasley pitched against the Oaks, he and Stengel tried to “out-showboat each other.” On June 16, Beasley pitched the final two innings against the Oaks in the first game of a doubleheader at Emeryville, California. “Using a long, tricky and different windup on every pitch as the crowd howled at the sideshow, the Nevada schoolteacher held them hitless.” Meanwhile, Stengel “mimicked Beasley’s weird gyrations from the third base coaching box for an added comedy touch.”10

Years later, Stengel told these stories about the hilarious hurler:

Well, Beasley had this glove with holes in it and he’d have most of a can of talcum powder in it. Before he’d pitch he’d pound that glove all over, down between his legs, over his head and by the time he threw, the ball would come out of this big cloud of dust and you could hardly see it. The first time he did it to some of the guys they laughed so hard they had to drop their bats. Then he’d strike them out.

When the umpire would make a call he didn’t like he wouldn’t say nuthin,’ just walk up to the plate, take a brush out of his pocket and dust it off. Those umpires were so surprised they’d just stand there.11

But not every umpire tolerated his antics. In the final game of the 1947 season, Beasley delivered three consecutive pitches that umpire Pat Orr called balls. Beasley then walked to the plate, “whisked a whisk broom out of his back pocket and dusted off the platter before the very eyes of the arbiter.” Orr promptly ejected Beasley from the game. In protest, “Oakland fans showered the Emeryville field with hundreds of [seat] cushions. . . . It probably was the first time in history that hometown fans showered an umpire for ejecting a rival player.”12

Indeed, Beasley was popular in every ballpark. But Dick Bartell, a humorless, hard-nosed former major leaguer who became manager of the Solons in 1947, didn’t like him. One time Beasley pitched a grapefruit painted white to Bartell in batting practice. Bartell hit what he thought was a baseball and got juiced. He was not amused. And then there was the “Mad Russian” Lou Novikoff incident. Beasley himself tells the story best:

Well, Lou Novikoff was a great hitter down from the Chicago Cubs and playing in the Coast League and hitting home runs against everybody. And this is burning Bartell up. He’s beat us two games already with home runs. So Bartell gets all the pitchers in the clubhouse before the game, and he tells them, “Now, I’ve pleaded with you. I’ve asked you. I’ve told you how to pitch him, and you pay no attention to me. Anybody that throws a pitch above his belt—it’s going to cost you a hundred dollars. And that’s it. No pitch above his belt.”

All right. We go out to play the game now. Guy Fletcher starts, and I’m in the bullpen along with two or three other guys. Novikoff, first time up, Fletcher gets a pitch a little high, and Novikoff hits it out of the park. Bartell comes charging the mound. Fletcher’s out of there, cost him a hundred bucks. . . . [Now I come] in from the bullpen. And I get by for a couple of innings. Novikoff comes up again. Bartell gets up from his seat, and he’s on the steps of the dugout already and motions, “Down, down, down, keep the ball down.” So all right. I wind up and roll it on the ground all the way to the plate. Bartell comes charging out of the dugout. . . . The crowd is laughing. . . . And Novikoff is laughing. The umpires are laughing. Everybody’s laughing but Bartell, and he comes out [and says to me], “What the hell you doing?” And I said, “Protecting my hundred dollars.”13

At Bartell’s insistence, the Solons traded Beasley to the Seattle Rainiers on July 31, 1947. Beasley pitched for Seattle in 1947 and 1948. He did not play in 1949, choosing instead to attend summer classes at Stanford. He returned to minor-league baseball the following summer as a member of the Vancouver (British Columbia) Capilanos of the Western International League.14

Beasley pitched for the Capilanos in 1950 and 1951, and briefly in 1954 at the age of 44. When he wasn’t pitching, his humorous coaching entertained the fans. Against the Salem (Oregon) Senators on July 5, 1954, Vancouver’s Ed Murphy took a lead off first base and could have used some help from Beasley, the first-base coach.

Suddenly, Gene Johnson, the Salem pitcher, whirled and picked off Murphy “when Beasley let Murphy get too far off the bag. Beasley, knowing it was his responsibility, ducked in chagrin and dashed for the dugout. . . . He emerged soon after, carrying an oversized bit of luggage and waving goodby sullenly to [Vancouver manager Bill] Brenner and the crowd, but the only tears from anyone were tears of laughter.”15

Beasley did leave professional baseball after the 1954 season, but he continued to coach high school baseball. Fred Dallimore was “the star pitcher on Beasley’s 1962 state championship baseball team at Reno High.” Dallimore, who later coached at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), for 23 seasons, said this about Coach Beasley: “His love and appreciation for the game of baseball was second to none. He was one of the most knowledgeable baseball guys I’ve ever known.”16

Beasley was a sought-after speaker, and he would entertain his audience with amusing anecdotes from his baseball career. He customarily finished each talk by reciting Casey at the Bat, the classic baseball poem from 1888.

A man of many interests, Beasley “played piano and drums and had poetry published; became interested, and sufficiently proficient, in magic to perform in night clubs; [and] pursued an interest in sociology by doing research projects in the slums of New York City and Boston.”17

But more than anything, Beasley loved teaching. After leaving Reno High School in 1974, he taught special education and adult education classes in Washoe County, Nevada, for more than 20 years; he was still teaching in his 90s. In 1989 he received an honorary doctorate in education from UNR.

Beasley and his wife had no children of their own, but over the years they cared for dozens of foster children and adopted 17 of them. In the elementary school that bears his name, there is a trophy case displaying memorabilia from his baseball career. He enjoyed visiting the school and entertaining the children by telling stories and performing magic tricks. In failing health for nearly a year, Beasley died in Reno on July 17, 2004. He was 94.18

On May 3, 2005, the Nevada State Senate unanimously adopted a resolution “Memorializing eminent educator and coach Bud Beasley. . . . Bud Beasley will long be remembered and greatly missed by his many thousands of students as a teacher and coach who truly cared about them and their futures,” it said. He “set the standard that all educators and coaches should strive to meet.”19

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Tom Schott, and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Ancestry.com (accessed November 2019).

Hoadley, Richard, ed., “Bud Beasley: Nevada Educator, Coach, and Athlete,” Transcript of interviews conducted by Dwyane Kling in 2001, University of Nevada Oral History Program, available online at archive.org/details/BeasleyBud.

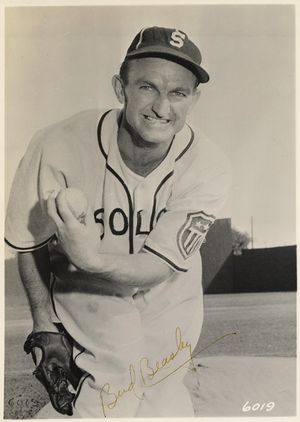

Photo credit: 1947 Sunbeam Bread baseball card depicting Bud Beasley on the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League.

Notes

1 Alf Cottrell, “Alfalfadust,” Vancouver [British Columbia] Province, June 15, 1954: 13.

2 1910, 1920 & 1930 US censuses.

3 Intvw transcript, Richard Hoadley, ed., “Bud Beasley: Nevada Educator, Coach, and Athlete,” 2001, University of Nevada Oral History Program, archive.org/details/BeasleyBud, accessed November 2019; Siobhan McAndrew, “Bowling with Beasley,” Reno Gazette-Journal, March 30, 2007: 1C, 6C.

4 Alf Cottrell, Vancouver Province, June 30, 1950:11.

5 “Sacs Triumph in 17th Frame,” Los Angeles Times, Sept. 3, 1944: II-5; “Caps Defeat Bears Twice,” Vancouver Province, August 1, 1951: 16.

6 Carl Digino, “Nevada Sports,” Reno Gazette-Journal, Jan. 23, 1954:8; Jack Hewins, “Bud Beasley Is Back with Seattle, Everybody’s Happy,” Reno Gazette-Journal, June 1, 1948: 13.

7 John B. Old, “Prof. Beasley (M.A.-Columbia) Mixes Psychology with Pitches,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1945: 6; see note 3, Hoadley, 106.

8 See note above, “Beasley Mixes Psychology.”

9 Paul Bauman, “Beasley, 74, Runs in the Fastest Lane,” Reno Gazette-Journal, May 9, 1985: 1B, 4B.

10 Ibid.

11 Ed Levitt, “Lefty Now Number 1,” Oakland Tribune, May 22, 1966:45, 54.

12 Walter Judge, “Oaks Split in Windup,” San Francisco Examiner, September 29, 1947:19, 21.

13 See note 3, Hoadley, 95, 96.

14 Ibid., 130.

15 A.C. Jones, “The Sportmeter,” The Salem] Capital Journal, July 8, 1954: III-1.

16 Ibid. Guy Clifton, “Longtime Area Coach, Teacher Bud Beasley Dies,” Reno Gazette-Journal, July 20, 2004:1, 3.

17 Bob Nitsche, “Bud Beasley Doesn’t Want to Be Remembered as Just an Athlete,” Reno Gazette-Journal, August 27, 1965:1, 7.

18 Janice Hoke, “Beasley Marks 90th at Namesake School,” Reno Gazette-Journal, December 9, 2000: 1C, 4C.

19 Nevada Senate Journal, May 3, 2005, 1251, Leg.state.nv.us/Session/73rd2005/Journal/Senate/Final/sj086.pdf, accessed Feb. 3, 2020.

Full Name

Arvel Lewis Beasley

Born

December 8, 1909 at Melrose, NM (US)

Died

July 17, 2004 at Reno, NV (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.