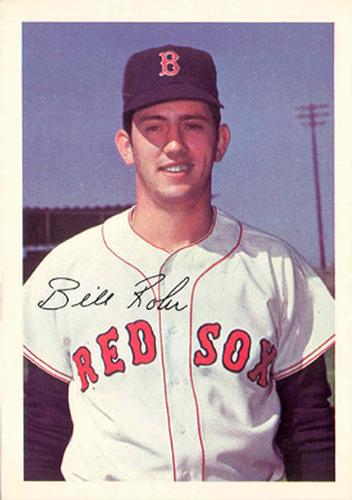

Billy Rohr

William Joseph Rohr was born on July 1, 1945, in San Diego, California, right in the middle of the baseball season. Rohr began playing baseball when he was 8, and despite weighing only 145 pounds in high school, he finished his career at Bellflower High with a 26-3 record, pitching four no-hitters for his varsity team.1 After graduating in 1963, Rohr was signed by Jerry Gardner of the Pittsburgh Pirates on June 15, 1963, paid $25,000, and sent to rookie ball in Kingsport, Tennessee of the Appalachian League.

William Joseph Rohr was born on July 1, 1945, in San Diego, California, right in the middle of the baseball season. Rohr began playing baseball when he was 8, and despite weighing only 145 pounds in high school, he finished his career at Bellflower High with a 26-3 record, pitching four no-hitters for his varsity team.1 After graduating in 1963, Rohr was signed by Jerry Gardner of the Pittsburgh Pirates on June 15, 1963, paid $25,000, and sent to rookie ball in Kingsport, Tennessee of the Appalachian League.

The Pirates tried to keep Rohr away from other teams, hiding his obvious talent by placing him and some other promising prospects on the disabled list the 1963 entire season—leaving them inactive when they were perfectly healthy. The strategy failed miserably. Mace Brown, a Red Sox scout whom Rohr would later call “one of the nicest men I have ever met … as well as a great pitching coach,” was alerted, and in November, Rohr was drafted by the Red Sox.2

Starting out with Wellsville of the Class-A New York-Pennsylvania League in 1964, Rohr finished 11-9 and pitched eight complete games, demonstrating the endurance the world would glimpse briefly three years later. The next season he started out with Winston-Salem, and after dazzling Carolina League batters for two months (7-3, 2.93), he was promoted all the way to Triple-A Toronto, where he finished 6-10 but with a fine 2.73 ERA. Pitching for manager Dick Williams, Rohr remained at Toronto in 1966, logging a 14-10 record and tossing 10 complete games.

His accomplishments led to a spring training invitation from the parent Red Sox in March of ’67, under the direction of Williams, recently promoted himself. With a great changeup added to his repertoire3, Rohr easily nailed down a berth on the major-league team on April 6, pitching six innings in a 4-1 win against the Tigers in Winter Haven.4 Heading into the season, Rohr was the team’s third starter.

On the night of April 13, 1967, 21-year-old Billy Rohr tossed and turned in his bed in a New York hotel room, so nervous about his major-league debut the next day against Yankee great Whitey Ford that, instead of sleeping, he spent time analyzing the Yankees lineup with Jim Lonborg.5 Just as nervous as Rohr was rookie Russ Gibson, who had taken a decidedly different path to the majors. Gibson, a 28-year-old catcher who would also be making his major-league debut the following day, had toiled away in the minors for 10 years and was contemplating hanging up his spikes when the Red Sox called to invite him to spring training in 1967. Though they had taken unique journeys to the majors, Rohr and Gibson’s paths converged at a 60-foot, 6-inch stretch of land on the infield at Yankee Stadium.

April 14 was Opening Day at Yankee Stadium. The monuments in left-center field stared across the diamond into the Yankees dugout, where Mickey Mantle, who would be honored in Monument Park himself two years later, sat on the bench, waiting for the game to start. Whitey Ford, one of the most fearsome pitchers in Yankee history, but nearing the end of his great career, was warming up in the bullpen. Rohr was set to make his first major-league start that day, while Ford would be making his 432nd. But Mantle and Ford were aging, the Yankees weren’t favorites to finish high in the American League that year, and those monuments in the outfield only seemed to mock the Bronx Bombers, as a small crowd of about 14,000 entered Yankee Stadium.

Rohr says he can only remember being extremely nervous, and announcer Ken Coleman told fans that the rookie pitcher looked a bit scared as he stepped to the mound, ready to begin the bottom of the first inning, working with a 1-0 lead that came from Reggie Smith’s leadoff homer. Dennis Bennett, a Red Sox pitcher who, a day later, would lose the second game of the series, 1-0, to Mel Stottlemyre, told Coleman, “If he gets by the first inning, he’ll be okay. But he’s a nervous wreck right now.”6

However nervous Rohr may have been, the first inning was uneventful and the lanky southpaw showed no sign of nervousness as he coolly retired Horace Clarke, Bill Robinson, and Tom Tresh. The second inning saw Rohr’s first major-league at-bat, a groundout. In the second and third innings, Rohr retired the Yankees in order again, and the crowd began to stir. In the fourth, Rohr walked two but stranded them on the bases, and the murmurs began to come from the stands. “I knew I was catching a no-hitter,” Russ Gibson said, “and he knew he was throwing one.”7

By the sixth inning, with everyone fully conscious of what Rohr was doing, Yankee right-fielder Bill Robinson slashed a hard grounder up the middle, striking Rohr in the left shin, which he clutched in pain as the ball ricocheted directly to Joe Foy at third base. Foy threw to Scott at first in time for the out, and it was Rohr’s first major-league assist, but it left him walking gingerly for a good five minutes. Trainer Buddy LeRoux rushed out with manager Dick Williams, ready to pull the young pitcher from the game. Rohr told his manager that he felt all right, but Williams worried that Rohr would hurt his arm by favoring his leg. He told Gibson that if Rohr showed any signs of deviating from his usual pitching motion, to have the rookie yanked immediately. An inning later, Gibson informed Williams, “The kid has better stuff than he had before he got hurt.”8 Rohr limped for the rest of the game.

As Rohr got the last out in the sixth inning and headed to the bench, he found himself sitting in solitude. No one talked to him as he iced his leg by himself on the right-hand side of the dugout. It is baseball superstition: One does not talk to a pitcher throwing a no-hitter–or mention it to anyone else, lest he jinx it. And so, in his first major-league start, Billy Rohr sat, by himself, marooned in a sea of people, all alone to realize what was taking place.

In the top of the eighth inning, third-baseman Joe Foy’s two-run homer gave Rohr a three-run lead, and, with tension mounting in the stands, he took to the mound as the now-desperate Yankees struggled to find a way, any way, to get a hit. Yankees manager Ralph Houk sent up Mickey Mantle as a pinch-hitter to lead off the bottom of the eighth, hoping to crack Rohr’s aura of calm assuredness. Mantle received a huge ovation from the Yankees fans–but paradoxically an even greater one after he flied to Tony Conigliaro in right.9

The next batter, Lou Clinton, gave the Sox a scare when he reached on a throwing error by Rohr and advanced to second on the walk that followed, but Bill Robinson grounded into a double play, and Rohr was only three outs from baseball history.

“We wouldn’t bunt on him when the game got into late innings,” Ralph Houk said later. “It was going to be a clean hit or nothing.”10 As Rohr got ready to face Tom Tresh to start off the ninth inning, a funny thing happened, something that, for some odd reason, seemed to stick in the heads of all those watching. He paused, looking around the infield. Ken Coleman thought that he was “establishing a magical bond with each of his teammates, a connection that, in some wordless way, help preserve the no-hitter.”11 Writer Ed Linn said that Rohr “turned slowly around as if he were checking his defense.”12 Sportswriter Bill Reynolds was listening on the radio, but even he remembers Rohr “looking around at his teammates.”13 Rohr laughs at the idea that he was checking his defense. What could he do? Reset them? The truth is, Rohr says, he was soaking in the moment. Turning back to the task at hand, Rohr ran the count to 3-2, and the play of the game took place. Tresh, looking for a pitch to hit, got a good one, and lined it to deep left field. Behind the plate, Russ Gibson cursed silently, “Well, there goes the no-hitter.”14

Among all the people who saw the play, there remains a consensus that there is no way Carl Yastrzemski, who was playing shallow to prevent a Texas-league single, could ever have been expected to catch it. Ken Coleman provided the best description of the event in his diary:

[Tresh’s] drive to left over the head of Carl Yastrzemski left a rising trail of blue vapor… At the crack of the bat, Yaz broke back, being guided by some uncanny inner radar. Running as hard as a man fleeing an aroused nest of bees, Yaz dove in full stride and reached out with the glove hand in full extension, almost like Michelangelo’s Adam stretching out for the hand of God. At the apex of his dive, Yaz speared the ball, and for one moment of time that would never register on any clock, stood frozen in the air as if he were Liberty keeping the burning flame aloft.15

In a record album released after the 1967 season entitled The Impossible Dream, Coleman’s call of Yaz’s catch is immortalized forever in black vinyl. “Fly ball, to deep left …Yastrzemski is going hard … way back … way back … and he dives and makes a tremendous catch! One of the greatest catches I’ve ever seen! … Everybody in Yankee Stadium on their feet.” All eloquent imagery aside, Yaz ran toward deep left, dove with his back to the plate, caught the ball with his glove extended, hit the grass with his left knee first, somersaulted once, came up with the ball in his bare hand held high, and fired the ball back to the infield. For Will McDonough of the Boston Globe, the catch was a moment that defined the entire rivalry between the Yankees and the Red Sox: “When I think of the Yankee-Red Sox rivalry, I don’t think of Williams or DiMaggio. I think of the catch Yaz made in the Stadium to save the no-hitter for Billy Rohr.”16

For a brief moment, the crowd of Yankee fans turned completely bipartisan, rooting for their own player to record an out, something that probably has not happened since and may never happen again with the enemy Red Sox in town. When Joe Pepitone flied out on the next pitch, the cheers reached a fever pitch for Rohr. A month before the Pirates drafted him, on May 11, 1963, Rohr had looked on as Sandy Koufax no-hit the Giants at Dodger Stadium. Now, four years later, he was one out away from joining Koufax.

As Elston Howard stepped to the plate, Dick Williams trotted out to the mound, as Rohr took a little breath and was reminded by his manager that Elston Howard loved to swing at the first pitch. As play resumed, Rohr heeded his manager’s advice, and Howard swung at a bad pitch, low and away. After two more pitches, and the count at 1-2, Rohr split the plate with a fastball. Umpire Cal Drummond called it a ball, but to this day, Russ Gibson maintains that the pitch was most certainly a perfect strike. After another ball that ran the count full, Gibson called for Rohr to throw Howard a curveball, hoping that Howard, having seen only fastballs all day, would be looking for a heater. But with one swift, sad stroke, Howard looped a shot over second baseman Reggie Smith’s head, where it softly landed in front of a disappointed-looking Tony Conigliaro. When Howard reached first base, he was surprised to hear boos and hoots. It was, he noted wryly, the first time he had ever been booed for a base hit in his home park. Howard was left stranded on first when Charley Smith flied out on the first pitch he saw, ending the game.

Later on, Williams would agonize over his decision to go out to the mound. “I told him I’ve beaten myself over the head about that trip to the mound. … He had one shot at fame, and my meddling may have blown it for him.”17 Rohr’s opinion was that while Williams had no business coming to the mound at that moment, the hit was not his fault–the manager isn’t the one who throws the pitch. Rohr was good humored about the moment, for it wasn’t the first time glory had slipped from his grasp. In 1966, pitching for Toronto in the International League against the Yankees Toledo farm team, Rohr had a no-hitter going with two out in the ninth–but was unable to close out the game, giving up a hit to a Yankees prospect named Mike Ferraro.18

After the game, congratulations began to flood in. Jacqueline Kennedy, who was in attendance with her son John-John, came by the clubhouse to meet Rohr, who happily signed a ball for the former First Lady’s son, to the child’s great delight. It was a proud moment as well for Rohr, who had been deeply affected by the assassination of President Kennedy. “After I pitched the game,” Rohr remarks, “I got to speak on the phone with Koufax and Drysdale. That was a huge thrill for me, because I had seen Koufax throw his own no-hitter and I was a Dodgers fan growing up. Andy Warhol once said that everyone has their 15 minutes of fame–that was my 15 minutes.” Indeed it was.

On April 16, Rohr made a brief appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, appearing with Nancy Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and Count Basie. He also received a new contract from the Red Sox, upping him from $8,000 to $9,000 a year. The box score in the Boston Globe the next day was entitled “And The Crowd Rohr-ed.” Boston Mayor John Collins sent a telegram: “You gave Boston an unforgettable day. Red Sox fans everywhere salute you on a fine pitching performance. May today’s victory be the first of hundreds in your major league career.”19

Unfortunately for Rohr, it was not. He followed with another solid win on April 21 in which he nearly pitched a shutout (only to have it broken up in the eighth, when his personal tormentor, Elston Howard, singled in the only Yankees run). In his next three starts, though, he was knocked around by opposing batters, giving up 12 runs and 15 hits in 7 2/3 innings. After a relief appearance on May 16, he threw another excellent game on the 21st, allowing just one earned run in 7 1/3 innings without earning a decision. Two ineffective starts later, he was sent to Triple-A Toronto and never started another ball game for the Red Sox. In September, back with Boston, Rohr pitched poorly in one game in relief, was demoted to Louisville after the year ended, and soon after the start of the 1968 season, was sold to the Cleveland Indians.

His tenure with the Indians was short, and after 17 games for Cleveland in 1968, finishing 1-0 but with a 6.87 ERA, Rohr was again sent to the minors, where he bounced from team to team in the Eastern, Southern, International, American Association and Pacific Coast Leagues before retiring in 1972.

In 2007, Rohr is a medical malpractice attorney in California, close to his hometown and to where he went to law school at Western State University after his career ended. Every year on April 14, he gets a call from some reporters, and his name inevitably appears in a “This Day in Baseball History” article. Rohr is different from some ballplayers. Many athletes who have had near brushes with history are bitter about the fleeting touch of fame, hating the memory of the bad break that made them a footnote instead of one of the sporting world’s greatest heroes. Not Rohr.

Bill Rohr (yes, it is Bill now) revisits the memory with a quiet clarity that is pleasant to be exposed to. Nothing fazes him, not Mickey Mantle at the plate in the eighth inning, or an unhappy memory of a mediocre season with the Toledo Mud Hens. When he has a quiet moment at home on the evening of April 14, he does get a bit nostalgic, but it’s on his own time, and the experience of that Opening Day is something that he remembers with pleasure, even 40 years later. People always tell him that they remember the game, and knew people who were there. This is a humorous point for Rohr, who laughs that if all those people had indeed been there, there would have been “175,000 people in Yankee Stadium instead of just 14,000.”

Rohr has been back to Fenway a few times since the end of his playing days. He remembers one time in particular. It was June 6, 1983, Tony Conigliaro Night at Fenway Park, a reunion for the 1967 team and a fundraiser to help defray the rising medical costs of their former right-fielder, who had played behind Rohr on that Opening Day at Yankee Stadium.20 Later that evening, Buddy LeRoux, the former trainer who had tended to Rohr on the mound in the sixth inning when he was hit by Robinson’s grounder, stood up and announced that he and limited partner Rogers Badgett had taken over the Red Sox front office from principal owners Jean Yawkey and Haywood Sullivan, and that he was now in charge. Rohr and the other players gaped. A confrontation erupted inside the organization, one that would not be resolved until after a long and drawn-out legal battle.

Rohr’s moment in the sun, though not unheard of in baseball, was considerably more significant than any other. Rohr’s moment of masterful pitching in the national spotlight is viewed by many as a catalytic stimulant to the Red Sox season, which was initially projected as just another typical Red Sox season in the ’60s–one that promised to deliver failure and frustration. Despite the fact that the Yankees were steadily declining, there was always something special about beating their East Coast rivals, and by winning in the Bronx, the Red Sox gained the self-confidence they lacked as the season got under way.

“Billy Rohr was 1967,” Peter Gammons once wrote, “even if he only won two games and was out of town by June.”21 To casual baseball fans who witnessed the year of 1967, Billy Rohr truly was a one-hit wonder, but to more philosophical baseball fans, Billy Rohr’s moment of magnificence symbolizes so much more than a moment in the sun, or a very near miss. To a Red Sox fan who suffered through years of near misses, Billy Rohr’s one-hitter typified the experience of supporting the Red Sox: standing on the brink of perfection, but somehow falling just short.

Last revised: February 1, 2016

A version of this biography originally appeared in “The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium on the Field” (Rounder Books, 2007), edited by Bill Nowlin and Dan Desrochers.

Notes

1 Bill Reynolds. Lost Summer: The 1967 Red Sox and the Impossible Dream (New York: Warner Books, 1992), 6.

2 Author interview with Billy Rohr on February 23, 2006.

3 Rohr credits Mace Brown with this development as well.

4 Ken Coleman. The Impossible Dream Remembered: The 1967 Red Sox (Lexington, Massachusetts: Stephen Greene Press, 1987), 38.

5 Who, Rohr notes, was probably up a little later then he liked.

6 Coleman, 45. He would wind up losing 1-0 to Mel Stottlemyre in what many remember as an epic pitching duel.

7 Author interview with Russ Gibson, March 20, 2006.

8 Coleman, 45.

9 Henry McKenna. “Rohr One-Hitter Tops Yanks, 3-0,” Boston Globe, April 15, 1967.

10 Ibid.

11 Coleman, 44.

12 Ed Linn. The Great Rivalry: The Yankees and the Red Sox 1901-1990 (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1991), 260.

13 Reynolds, 7.

14 Gibson interview.

15 Coleman, 44.

16 Linn, 261.

17 Dick Williams. No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life Of Hardball (New York: Harcourt, 1990), 87.

18 “Narrow Miss Doesn’t Disturb Red Sox Rookie,” Los Angeles Times. April 15, 1967.

19 Coleman, 44.

20 In August, months after Rohr’s one-hitter, Conigliaro was hit in the face by a fastball from California Angels pitcher Jack Hamilton, an incident that was the first of a string of many medical problems.

21 Peter Gammons. “Musical Chairs on Yawkey Way,” Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson, Red Sox Century (Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 424.

Full Name

William Joseph Rohr

Born

July 1, 1945 at San Diego, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.