Otto Denning

\Baseball aficionados know that trades, sales, and waivers are a part of the game. The general manager of the 1951 Chicago White Sox was Frank Lane, who earned the nickname Trader Lane for his propensity to exchange players. His attitude must have filtered down through the organization because minor-league director John Rigney engineered a trade that season that swapped managers Otto Denning and Skeeter Webb between Colorado Springs and Waterloo. It was déjà vu for Denning because in 1947 he had been traded from Louisville to Milwaukee for a Brewers coach, Owen Scheetz.

In the 1700s after the Seven Years War, Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia, encouraged Germans to move to Russia and farm in uninhabited areas. Thousands moved into southern Russia. A century later conditions in Russia had deteriorated to the point where these settlers no longer wanted to live under the czars. Lured by promises of cheap farmland, a large contingent of Russians migrated to Kansas in the 1870s. Otto George Denning’s grandfather, Joseph, arrived in America in 1876 and moved to Ellis County, Kansas, to farm. He soon married and started a family that included Jacob Denning, Otto’s father. Jacob married Magdalene Windholz in the early 1900s and continued to farm on the prairie with the rest of the family. The couple had five children, Otto being the fourth son, born on December 28, 1912, in Hays, Kansas. A sister was born two years later. Jacob left farming and became a store clerk in Topeka before moving the family to Chicago in the 1920s and working as a machinist. Otto graduated from Lane Tech high school and played baseball for the school team.

The Lane Tech baseball teams were the toast of Chicago in the 1920s and ’30s. Coached by Percy Moore, they won numerous titles. Otto does not appear in the available 1931 box scores, but he is a fixture in 1932 as a catcher who batted third in the lineup. His finest performance was on May 6 when he drove in six runs in a win. The 1932 team won the city title.1

The Davenport (Iowa) Democrat and Leader on June 17, 1932, announced the acquisition of an outfielder from Chicago by the Davenport Blue Sox of the Class D Mississippi Valley League. The paper identified him as Otto Beming (sic) and said he was 22 years old (he was actually 19) and had previous experience in the Wisconsin State League (which was not in existence in 1931-32). Denning made his first appearance on June 19, playing right field, and was listed in the box score as “Deming.” He popped out and struck out in the rain-shortened six-inning game. In his second appearance his name was spelled correctly. On June 22 managher Cletus Dixon moved Denning to leadoff, where he went 2-for-3 with a double and a stolen base, drove in a run and scored one. The next day he hit leadoff again, going 3-for-5 with another double.

The Mississippi Valley League used 14-man rosters. There were also restrictions on the number of veterans (players with experience above Class D). Manager Dixon was constantly tinkering he with his roster; he used more than 30 players during the season. Despite a .367 average (11-for-30), Denning was relegated to pinch-hit duty after June 27. Dixon must have seen a huge upside in Denning’s talent because he kept him on the roster, frequently releasing more experienced players. The Blue Sox finished second to Rock Island in the first half of the season. In the second half they got off to a tremendous start, but had to hold off Cedar Rapids. On August 21 Denning delivered a ninth-inning pinch-hit single to plate the winning run in a 7-6 affair between Davenport and Cedar Rapids. The Blue Sox went on to clinch the second-half title, but lost to Rock Island in the playoffs. For the season Denning appeared in 31 games and hit .260.

The Mississippi Valley League moved up to Class B in 1933, when the Depression brought on a 25 percent reduction in the number of leagues. In 1934 Davenport switched to the Class A Western League. Denning stayed with the Blue Sox through the 1936 season, playing in 431 games during his five seasons there, and hitting .297. He was primarily a catcher, but also saw action at first base and the outfield. He was sold to Elmira in the Class A New York-Pennsylvania League for the 1937 season.

Elmira was a Brooklyn Dodgers affiliate and Denning earned his first trip south with the Dodgers that spring. His stay was short and uneventful before he was returned to Elmira. The 1937 pennant race was hotly contested but Elmira emerged as the league champion. Denning found himself in a batting race with former Blue Sox teammate Cosmo Cotelle of the Albany team and George Case of Trenton. At season’s end they all had a .338 average. After double-checking the stats, league officials broke the tie and Cotelle came out a few ten thousandths of a point ahead of Case with Denning third. The Sporting News reported that “[H]e developed a knack for hitting curve-ball pitching … making him a feared batter in the pinches. Afield, he’s extremely versatile, going from catcher to outfield or first base with equal facility.”2

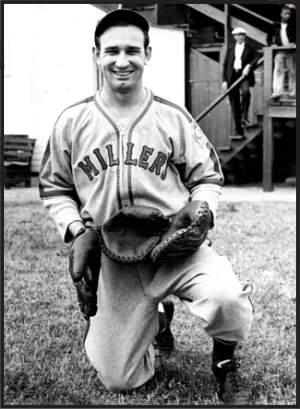

Denning’s contract was sold to Minneapolis, where he joined Ted Williams on the 1938 Millers squad that finished out of playoff contention despite Ted’s Triple Crown year, in which he batted .366. Denning saw limited action in 1938 and 1939 because of torn ligaments in his shoulder, but bounced back nicely in 1940 to hit .329 in 130 games. The Millers finished third in 1939, but were beaten in the first round of the playoffs by Louisville. Denning hit .329 again in 1941 with 17 homers and 105 RBIs as the Millers again made the playoffs and once again dropped the first round to Louisville.

After the 1941 season the Cleveland Indians needed another catcher to join veteran Gene Desautels and youthful Jim Hegan. In the Rule 5 draft, the Indians picked up the 29-year-old Denning. It would be up to new player-manager Lou Boudreau to select his starter. Desautels was a highly regarded defensive talent, but was weak at the plate. Hegan, just 21, was an up-and-coming prospect with a strong arm, good skills, and the potential to turn into a decent hitter. Denning was coming off four consecutive seasons at Minneapolis with a batting average over .300 and had been dubbed an all-star in the last two years. The torn ligaments in his shoulder hampered his throwing, but he believed, “I make up in accuracy what I lack in power. American Association runners didn’t take many liberties with my arm….”3

At spring training in Clearwater, Florida, Denning was injured while catching batting practice when he took a foul tip off his middle finger. Seeing his opportunity to make the big leagues, Denning kept quiet about the injury for a few days, but his batting suffered because he could not grip the bat. Trainer Lefty Weisman ordered X-rays on March 13 that disclosed a bone chip. Initial reports were that Denning would miss more than a month. Determined to escape life in the minors, he was back in the lineup on March 24 against Cincinnati and smacked a two-run single. By the end of spring training, Desautels’ defensive skills had earned him the starting nod. Denning was the backup and Hegan was sent to Baltimore in the International League.

Denning’s first major-league action came on April 15, 1942, in Detroit. He started at catcher, hit eighth, and went 2-for-4 with a double off Dizzy Trout in a 6-2 loss. He also threw out the first would-be basestealer, Ned Harris. This performance earned Denning the start the next day when he went 1-for-2 with a walk and a double in the 5-4 loss. Desautels handled the chores for three weeks until he suffered a broken fibula in a home-plate collision. On May 9 Denning took over as the number-one receiver and Jim Hegan was recalled from Baltimore as his backup. Denning was batting .333 at this time and had recorded his only major-league home run off Dick Newsome in Boston on May 4. From May 9 through May 18, Denning caught every game, including back-to-back doubleheaders. Defensively he did well, but he was a miserable 4-for-31 at bat. Boudreau then inserted Hegan as the starter for a little over a month. The youngster went 16-for-69 with 5 RBIs. Denning was given another chance in mid-June and fared only slightly better than before, going 10-for-47 at the plate.

Gene Desautels saw the bulk of the action for the remainder of the season. Because of injuries, Denning was pressed into outfield service for two games in late August and coach George Susce, a catcher, was activated. At season’s end Denning led the Indians catchers in at-bats, runs, and RBIs. He hit .210, Desautels .247, and Hegan .194. Denning’s May 4 home run was the only one recorded by the catchers.

Denning led Indians catchers with a .992 fielding percentage, well above the league average of .979. He threw out 17 of 46 basestealers for a 37 percent average, below the league’s 42 percent rate, but well ahead of Desautels’ 29 percent. On May 11 the Cleveland Plain Dealer commented, “Denning’s reputedly weak arm has not shown up yet. He has thrown out 4 of 6 runners.” The statistics are misleading for what they do not show. Only two teams in the league used the stolen base as a major weapon, Chicago and Detroit. Denning had four starts against them and gave up eight stolen bases in 11 attempts. Denning also led the Cleveland catchers in passed balls (5).4

Over the winter Hegan enlisted in the Coast Guard and first baseman Les Fleming decided to stick with his job in a war plant. During spring training at Purdue University’s indoor facility in Lafayette, Indiana, the Indians traded with the Yankees to bring in catcher Buddy Rosar and outfielder Roy Cullenbine. The addition of Rosar freed Denning to work at first base. He worked hard to learn the position and was rewarded with the starting job. Once again, his bat went cold and he got off to a 1-for-15 start. After 19 consecutive starts he was finally benched with a .191 average. After a week of pinch-hit duty, he returned to the lineup and pounded three hits and drove in two runs against the Yankees in a 9-2 win. He went on a six-game hitting streak after that and raised his average to .252, but showed none of the power that Boudreau was hoping for. A 3-for-22 slump followed and on June 4 the Indians sent both Denning and Eddie Turchin to Buffalo for first baseman Mickey Rocco. Supposedly, Boudreau asked Otto if he would like to see Niagara Falls for free. When he said he would, Lou replied “Good because we’re sending you to Buffalo.”5

Denning had a draft deferment because he worked in a defense plant in Chicago during the offseason. In 1944, while with Buffalo, he relinquished the deferment and was reclassified 1-A, eligible for the draft. He was called in for a physical in the summer but was not inducted. (Ken Keltner, the Indians’ third baseman, also gave up his deferment and was subsequently inducted into the Navy.)

The Buffalo Bisons finished a distant seventh place in 1943. Denning caught, but also saw duty in the outfield and at first base. In 1944 the Bisons improved and finished fourth. Denning had his best power season, launching 21 homers to go with a .288 average and 16 stolen bases. Once again he split time, but saw more action in the outfield than at first base or catcher. The Bisons took Baltimore to seven games in the first round of the playoffs before succumbing to the eventual champs. Denning contemplated staying in his factory job in Chicago and not playing in 1945 with Buffalo. A trade was arranged and he was shipped to the Milwaukee Brewers. Owner Bill Veeck’s salesmanship and the proximity to home in Chicago coaxed him back onto the field. Denning was a fixture at first and hit .306 as Milwaukee won the regular-season crown in the American Association. He saw his playoffs ended in the first round by Louisville. That was Denning’s last full-time action. Hundreds of players returned from the war and went back into the game. Denning split 1946 among Milwaukee, Louisville, and Toronto. In 1947 he was with Louisville and Milwaukee before joining the coaching ranks for good.

Denning had always been popular with his teammates. He was easy-going and something of a prankster, but on the field he was a competitor. The Cedar Rapids Gazette of July 3, 1951, called him “vigorous and colorful.” Most importantly, Denning possessed a wealth of knowledge about the game. He was hired in 1948 to manage Pensacola (Florida) in the Class B Southeastern League. The Fliers were regarded as the preseason favorites, but got off to a slow start and were in fifth place on May21 when Denning resigned. He was out of the game for a month before the Oil City (Pennsylvania) Refiners in the Class C Middle Atlantic League took him on to replace manager Ray Dahlstrom. The team was 14-28 (.333) when Denning took over, and finished 50-76 (.397). Denning used himself in 34 games and feasted on lower-level pitching for a .368 average. He would have played more had he not suffered an arm injury in late July and been forced to the disabled list.

Denning returned to Oil City in 1949 and coaxed the team to fourth place. He played in 77 games and had a league best .385 average. He played 31 games at catcher and split the rest between first base and the outfield. Oil City was a Chicago White Sox affiliate and Denning was managed Waterloo (Iowa) in the Class B Three-I League in 1950. The White Hawks had some good young prospects, including catcher Red Wilson, who went on to a ten-year career in the major leagues. Denning directed the team to a third-place finish and proved to be a fan favorite. The season ended when Waterloo was swept by Danville in the first round of playoffs. Denning returned to Waterloo in 1951, but the team struggled. The Waterloo Courier took issue with him for not living in Waterloo, especially when Denning took a few days in June to return to Chicago for his son’s illness. Soon after, he was suspended indefinitely by the league for an incident in a game with Cedar Rapids. The suspension was reduced to two games. On July 3 the White Sox brass decided to send Denning to Colorado Springs in the Class A Western League and bring that club’s manager, Skeeter Webb, to Waterloo. The White Sox brass claimed the new start would help both squads. The Waterloo Courier opined that the team “needed a taskmaster to whip it into winning form.” Neither Webb nor Denning could turn around the fortunes of their new teams. Over the winter, Denning was replaced by Don Gutteridge in Colorado Springs.

In 1952 Denning applied for the job as manager of Burlington in the Three-I League. When he missed out on that job, he started a 24-year career in the post office in Chicago.

Denning wed Agnes Lalowski on March 4, 1935, in Chicago. The couple raised two boys and two girls, all of whom remained in the Chicago area. Otto became involved in youth baseball leagues and was a frequent clinician and guest speaker. He also loved to attend games, and became a bleacher bum at Wrigley Field long before the “Bleacher Bums” gained notoriety. After Bill Veeck sold the White Sox in 1981 it was not unusual for Denning, Veeck, and photographer George Brace to attend Cubs games together.6

Otto Denning died of a heart attack on May 25, 1992. After services he was buried in St. Joseph cemetery in River Grove, just outside Chicago.

Denning was the uncle of Chris Bourjos, who played in 13 games for the San Francisco Giants in 1980, and the great-uncle of outfielder Peter Bourjos, whose career began with the Los Angeles Angels in 2010.

Sources (other than those mentioned):

Greeley (Colorado) Daily Tribune

Joplin (Missouri) Globe

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Oil City (Pennsylvania) Derrick

Richmond (Virginia) Times Dispatch

Rockford (Illinois) Register-Republic

ancestry.com

stewthornley.net/millersgames/1941

Notes

1 The Chicago Tribune was used as the source for Denning’s Lane Tech career.

2 The Sporting News, December 9, 1937.

3 Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 11, 1942.

4 All statistics come from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

5 Jerome Holtzman, “Dugout Fragrances and Sweet Memories,” Chicago Tribune July 1, 1986, C1.

6 Ibid.

Full Name

Otto George Denning

Born

December 28, 1912 at Hays, KS (USA)

Died

May 25, 1992 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.