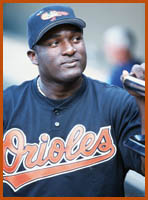

Calvin Pickering

As of 2016, 14 men from the U.S. Virgin Islands had played in the major leagues.i Calvin Pickering was the tenth, and the third of seven from the island of St. Thomas. He was an intriguing talent, with power to match his enormous size. “Picko” stood 6’5” and weighed 260 pounds at his fittest. As a result, the first baseman drew comparisons to Cecil Fielder (though he swung lefty), Mo Vaughn, and Boog Powell.

As of 2016, 14 men from the U.S. Virgin Islands had played in the major leagues.i Calvin Pickering was the tenth, and the third of seven from the island of St. Thomas. He was an intriguing talent, with power to match his enormous size. “Picko” stood 6’5” and weighed 260 pounds at his fittest. As a result, the first baseman drew comparisons to Cecil Fielder (though he swung lefty), Mo Vaughn, and Boog Powell.

Pickering was a 35th round draft pick in 1995 of the Baltimore Orioles and blossomed into one of their top prospects. Injuries and front-office decisions set him back for several years – his bulk was often a concern – but he fought his way back. Eventually, though, time ran out on his chance to be a big-league slugging star. He last played in the majors in 2005 and hung on in independent leagues through 2008.

Calvin Elroy Pickering was born on September 29, 1976. Although baseball references show him as being born on St. Thomas, he stated in 2012 that he was actually born in Texas. His father, Elroy Pickering, was serving there in the military at that time. In the early to mid-1970s, Elroy’s name appeared in Virgin Islands Daily News articles about the local men’s league in St. Thomas (he was a firefighter). Calvin’s mother, Ruby Hodge, also had three other children, two daughters and another son. Younger brother Kelvin Pickering played rookie-league ball for the Orioles from 1999 through 2001.

In 2011, Pickering told Andrew Martin of “The Baseball Historian” blog that he first became interested in baseball at age three while watching on TV with his grandfather, who was a big fan. “My mother always used to say that when baseball was on they couldn’t change the channel because I used to catch a fit and start screaming, so they would have to turn it back to the game.” He began playing street ball with friends at age eight and competed in youth leagues from the age of 10. His Little League was named for another major-leaguer from St. Thomas before him, Elrod Hendricks.ii

Like Hendricks, Pickering played as a teenager in the local men’s recreational league. His high school did not have a team. Fortunately, Calvin also had his aunt’s husband, Addie Joseph, who devoted much of his time to coaching the boys on St. Thomas. Calvin’s own local training wrinkle was 30-yard ocean sprints in water ranging from waist- to chest-deep.iii

Ellie Hendricks first noticed Pickering, aged 17, at a clinic in St. Thomas. Ellie got the sponsor, American Airlines, to let him bring along his old Orioles buddy Lee May as a helpful companion. In early 1999, Hendricks recalled that Calvin was “a fat kid walking around with a mitt that was held together by string. Lee and I looked at him and thought he was the worst athlete of the group.iv Later that year, he added, “Then Lee threw him some pitches, and said, ‘Hey Rod, I think this chunky kid’s got something!’” When Hendricks got back to Baltimore, he asked O’s first baseman Rafael Palmeiro, Pickering’s idol, to send the youngster a new first baseman’s glove. Several years later, when Pickering made it to his first big-league training camp, Hendricks asked Palmeiro if he remembered the story, which he did — whereupon Ellie introduced Pickering in person.v

A crucial step in Pickering’s development came when he moved to Tampa for his senior year of high school in 1995. Two of his aunts had preceded him, driven from the Virgin Islands by Hurricanes Hugo (1989) and Marilyn (1995). Aunt Lois went back for a vacation, saw Calvin play, and said, “It was then I knew he had to come back with me. He would go to school, he would have his dream.”vi

At King High, Coach Jim Macaluso wasn’t interested in Pickering at first, but he changed his mind after the big youth unloaded some tape-measure bombs in batting practice against the coach’s son. Macaluso recalled in 2010, “I remember the first time I heard it and 100 times after that, ‘Coach, I want to play in the big leagues.’ He was so sincere about it.”vii

Pickering was named to Florida’s all-state second team as a left fielder. He felt in his depth thanks to playing with adults. He also caught the eye of Orioles area scout Harry Shelton. Shelton, a Cubs farmhand in the ’80s, had just started out in the field, and Pickering was his first important find. In 1999, Shelton said, “I kinda liked him, he always hit good against the better pitching. There was a kid that I wanted to draft out of Hillsborough High, Dwight Gooden’s old school, and Calvin hit this guy pretty good, just like it was drinking water. A spit-image of Tony Gwynn, that’s who he looked like in left field, a big-buttocks type of guy. Despite that, though, he ran well, and that’s why I compared him to Gwynn. Calvin can steal a base.

“Power wasn’t his main focus then. Coach Macaluso drilled him as far as becoming a big guy that could hit for average. He’s not a big guy that just swings for the fences. He’ll hurt you by driving the ball to left field, and then when you make a mistake, he’ll really capitalize on it, and the next thing you know, Calvin Pickering’s 3-for-3 with two or three home runs.”

Shelton believed a lot of scouts were afraid of Pickering’s body structure, and even he didn’t know the youngster could play first base until he saw him do the splits in an American Legion game. “It’s really hard to say if any other teams had him in, I might have been the only one.” And since the scout had not built up clout in the Baltimore organization, that was another reason why Pickering went in the late rounds.

At the time, Shelton thought he had a “draft-and-follow” candidate. He reasoned, “Even if I can’t make it worth his while to sign now, at least he’ll be able to go to a junior college locally.” But when he went to the Orioles minor-league complex and saw no first-base prospects, he told Pickerinh, “Now is the time, you can play every day.”

In the low minors, Pickering made many baseball people snap to attention. In his first Rookie League stop, he went 30-for-60 at Sarasota, but with only one homer. Harry Shelton advised him, “If you’re gonna be a first-base power guy, then you have got to put the ball in the seats.” At Bluefield, West Virginia in 1996, Calvin started driving the ball and finishing high with his hands, and he became the first Oriole to be named the club’s minor-league player of the year from the Rookie League level (18-66-.325 in 60 games).

Pickering enjoyed a fine 1997 season at both low-A Delmarva and the Hawaii Winter League. He tied for the HWL lead with 10 homers, and was deemed ready to skip to Double-A Bowie. There he was Eastern League Player of the Year in 1998, winning the home run and RBI legs of the Triple Crown.

The Orioles called Pickering up that September. His first start in the majors came as a designated hitter against knuckleballer Steve Sparks (then with the Anaheim Angels), who struck him out three times. But then he excited all of the Virgin Islands when he hit his first two big-league homers against two premier pitchers, David Cone of the Yankees and Pedro Martinez of the Red Sox. As Pickering told Andrew Martin, the hit off Cone was his favorite moment as a professional. He also had a nice anecdote about Martinez, whom he rated as “most definitely” the toughest pitcher he ever faced. “He threw all fastballs and I hit a home run, so the third at-bat he threw me all change-ups and I flew out. So when I was heading back to the dugout, he told me, ‘Pick, you showed me that you can hit my fastball, so I wanted to see if you could hit my change-up.’ I just started laughing on the way back in.”viii

Pickering went to the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1998-99 but did little. According to Shelton, he was tired, and “after he had got a taste of the big leagues, Calvin was thinking only of working out and getting ready for spring training.” The Orioles decided not to resign Rafael Palmeiro that offseason, but in effect they made an even-up trade by signing Rangers free agent Will Clark. The Gold Glover generously took the prospect under his tutelage in spring training, working on his main deficiencies, footwork around the bag and throwing.

It was a blow to have the way blocked, though, when many teams would have given a young player an extended opportunity. Upon being sent down, allegedly a misty-eyed Calvin tossed his cap in a clubhouse trash can.ix When Clark’s thumb was broken, Pick was called up briefly, also starting in the first exhibition game against Cuba on May 3. He then went back to Triple-A Rochester, but returned again in September. In between, he represented the Virgin Islands as part of the World Team at the All-Star Futures Game in Boston’s Fenway Park.

Overall, 1999 was a mixed bag, as a strained shoulder prevented the slugger from getting in a groove early. That summer, Ellie Hendricks noted, “He’s gonna be all right. Sometimes it takes a while to realize that life is not as easy as you think it is. I think he thought it was a piece of cake, because it had been up to that point. That was a big jump, and plus, playing in a place that’s cold all the time, he’s not used to that.” Indeed, as Ellie predicted, Pickering heated up along with the weather. Shelton agreed: “The weather gets warm, and he just explodes. You just cannot pitch to the guy.”

After the big-league season ended, Pickering played for the Scottsdale Scorpions of the Arizona Fall League. It was a fine opportunity to work on both hitting and fielding, as the manager was former Orioles superstar first baseman Eddie Murray, a three-time Gold Glover. Calvin batted .322 but connected for just 2 homers in 21 games.

His shoulder finally healed properly, Pick had a moderately successful spring training in 2000. He homered in both his first and last at-bats of camp, and drew a lot of walks as usual. However, he was still stuck behind Clark and Jeff Conine, as well as DH Harold Baines. Thus he was assigned to Rochester once again. Calvin stated “They already know everything I can do. I have nothing else to prove. I just have to wait my turn.”x

It would have helped his case, though, to post big power numbers for the Red Wings and play well in the field – where in fact he did need to show more. Unfortunately, the 2000 season turned out to be a nightmare. A slow starter throughout his career, Calvin got no help from nature. The early April weather was filthy even by upstate New York standards: snowy, rainy, and generally unfit for baseball and islanders. As Pickering’s slump persisted, the Wings even had him batting eighth in the lineup at times.

And just as he showed signs of emerging in the summer again, another injury shelved him for the year. The first diagnosis was knee tendinitis, but it turned out a torn quadriceps muscle was causing the pain. The tear may well have been related to excess weight, which became a problem again. After reporting to Bluefield at 320 pounds back in 1996, Calvin went to the Duke University weight-loss clinic.xi It worked, and he had been monitoring his diet. Reportedly, though, he was back over the 300 mark.

Originally it was thought that surgery wasn’t needed, but Shelton counseled that it would be the wisest course of action. Winter ball would have made sense after missing the whole second half of the season, but Picko was just about finished rehabbing the injury when spring training 2001 rolled around.

The Orioles trimmed many older and expensive players from their roster in 2000, including Will Clark. But the outlook for Pickering in Camden Yards remained dim. The Orioles had acquired Chris Richard, a slightly older first baseman, from St. Louis. The club then outrighted Calvin to Triple-A in November and put more obstacles in his path after that, signing veteran free agent David Segui and picking up Jay Gibbons in the Rule V draft.

Although Calvin’s stock had declined with the O’s front office and fans, VP Syd Thrift stated, “You never evaluate an injured player in this business. That’s a trap.”xii Director of organizational instruction Tom Trebelhorn added, “It’s too bad Pick wasn’t available when things started happening [in July]. This would have been his opportunity, I believe. Instead, they put another left-handed-hitting first baseman out there. It’s unfortunate, because I believe Pick could have shown something.

“Some people are still high on him. Some people are down on him. Some are in the middle. In my opinion, we have to get him well. He’s got value, perhaps to this organization but certainly within the industry. You don’t give up on that kind of power. This is a business and he is a commodity. Our challenge is to develop players and Pick has huge potential.”xiii

Under owner Peter Angelos, the Baltimore organization has been strongly criticized for its handling of young players. There was reason to think that Pickering’s confidence may have been harmed by all the free-agent signings. Still, criticisms of his maturity appeared at least partly valid too. In spring 2000, Eddie Murray said, “We all want to see some type of fire in him, for him to go somewhere and take that extra 20 minutes of fielding ground balls. He’ll come out and hit extra, but you can’t always work on your strengths.”xiv

Harry Shelton believed, “It’s more of a concentration thing, he has to take pride in it like he does his hitting. Personality-wise, he’s a great kid, very hard worker. You tell him that he can’t do something, that’s when he gets fired up to do it.” Shelton’s bottom line: “I signed this kid, and I know his makeup. He’s going to be determined to show the Orioles that they made a mistake. They ain’t heard or seen the last of him.”

Pickering clearly had an incentive to get back in top condition and re-establish himself as a contender in the majors. He did exactly that in 2001. By keeping the poundage within reasonable bounds, he showed that he was a pretty agile big man. After working his way back into game shape as the DH, Calvin reclaimed the first-base job at Rochester. He drew plaudits for working on his defense, but better yet, enjoyed a big comeback with the bat. Picko’s 99 RBIs led the International League. Though he struck out a lot, he continued to draw walks as well.

But this saga grew stranger. In late August, Baltimore traded Pickering to Cincinnati for “future considerations,” which one observer likened to “a bucket of balls.” Then after making it back to the majors for four games with the Reds, he was shipped off again. Reds GM Jim Bowden placed Calvin on irrevocable “special waivers,” probably hoping to sneak him through and open up roster options. However, Boston Red Sox GM Dan Duquette remembered that 1998 homer versus Pedro Martínez, and grabbed him for a look-see.

Picko performed well in his extended trial with the Red Sox and then returned to the Caribbean for winter ball in the Dominican Republic. Again, however, this was a brief experience. The Azucareros del Este sent an injured Pickering home in November. Then with the Bosox in spring training 2002, Calvin tore his other quad muscle, entirely wiping out the summer season.

That December, Pick hooked on with the Los Mochis Cañeros of the Mexican Winter League. Though he was still working his way back into shape, he swung the bat well and then helped Los Mochis win the Mexican playoffs. As a result, he got to play in the Caribbean Series. Unfortunately, this squad – which was criticized at home for its lack of native-born players – went 0-6 during the tourney.

Calvin’s Mexican splash prompted the Seattle Mariners to sign him to a minor-league deal in January 2003. The M’s released him that March, though, so again Picko turned to Mexico. This was another enjoyable comeback, as he hit .323 for Vaqueros de Laguna and nearly led the league in home runs, finishing in a tie for second with 25. Another heartening note was his much trimmer condition – down to 260 pounds. Pickering knew that he had to lose the bulk for the sake of his legs and knees.

This performance got the attention of the Cincinnati organization once again. The brevity of his stay with the Reds in 2001 was never really explained, but nonetheless, Calvin returned to Louisville. His hitting there remained brisk enough that a callup to Cincinnati appeared in order. But even though the Reds trotted some 55 players out during 2003, Picko was not one of them.

The 2004 season was much more encouraging, though. With Omaha in the Kansas City Royals organization, Pickering went on a spectacular early-season tear, with 11 homers in his first 12 games. He wound up with 35 in just 89 games before the big club called him up in August for the most extended audition of his career. Picko responded by surpassing his career totals in every major category.

Things were looking up for Calvin Pickering in spring training 2005. The Royals sent Ken Harvey down to Omaha, making Picko the Royals’ primary designated hitter and cleanup hitter. His wife, Jessica (maiden name Gonzalez, married October 13, 1999), also gave birth to their child that April, a son named Jacob Elijah.

Unfortunately, Calvin got off to an ice-cold start. Appearing in only seven games made it tough, but he hit just .148 with one home run and three RBIs. He struck out 14 times in 27 at-bats, while drawing only three walks.

Pickering stated, “I just need to clear my mind. Whenever the opportunity comes again, hopefully I’ll be ready.” He added, “Right now I’m not thinking about anything. I’m going to Omaha and I will keep working hard, and what happens, happens. I have no excuses. I’m going to give 110 percent. If it doesn’t work out, it doesn’t work out.”xv

Calvin hit well at Omaha during the rest of 2005 (.275-23-67 in 92 games), but the Royals released him at the end of that season. He returned to winter ball in Mexico, playing once again with Los Mochis. He supplied power (14 homers and 34 RBIs) but was suspended for disciplinary reasons towards the end of the season.

Picko signed with the SK Wyverns of the Korean League for 2006. He left Korea after roughly half a season, even though he had hit fairly well (.278-9-34 in 60 games). “I had a good time in Korea,” Pickering recalled in 2012. “It was fun playing there. But they needed pitching, so they had to make moves.”

Pickering, by then almost exclusively a DH, returned to the U.S. independent leagues. In 2007, he played 89 games for the Kansas City T-Bones of the Northern League, producing well (.310-18-83 in 89 games). Still, he didn’t receive any big-league offers, and he considered taking the 2008 season off to stay with his family in Arizona. The T-Bones released Calvin in March 2008, but he decided to join the Bridgeport Bluefish of the Atlantic League. His manager in Bridgeport, former big-league pitcher Tommy John, thought he still had a shot at the top level.

“He can hit,” John said. “He just has to get in shape. If he would get in shape, get a trainer, he can play for somebody. And with the money that’s being thrown out there now. . .I mean, this is my thinking, you’ve got to give it your best shot because there’s a ton of money out there for guys with far less talent than he’s got.”xvi

Yet after 65 games with the Bluefish (.265-8-41), he was let go in July. Returning to the Northern League, he exploded for 14 homers and 38 RBIs in 37 games with the Schaumburg Flyers. He had a three-homer outburst at Fargo on August 22. However, his pro career ended after the 2008 season. “I never officially retired,” said Pickering in 2012. “I started an academy with friends out here [in Orange County, California, where he lives with Jessica and Jacob]. I started coaching, teaching the kids the game.”

In recent years, Virgin Islanders have been scarce at the major-league level. When Callix Crabbe of St. Thomas came to the plate for the San Diego Padres on April 3, 2008, it marked the first time a V.I. player had appeared in the majors since August 6, 2005. The gap between Midre Cummings, who finished his career with the Baltimore Orioles, and Crabbe was more than two and a half years. Crabbe got into 21 games, the last on May 8, 2008, and did not make it back to The Show again. The drought ended briefly in 2015 when pitcher Akeel Morris appeared in one game for the New York Mets. However, two other St. Thomians, outfielder Jabari Blash and pitcher Jharel Cotton, reached the top level in 2016; Morris has since also made it back.

“I just got back from a visit a couple of months ago,” Pickering noted in 2012. “They got some talent down there. But nothing’s changed pretty much from when I was coming up. After Little League, they have to find something to continue playing.”

In 2011, Pickering looked back on his playing days with Andrew Martin. “I’m very proud of what I have accomplished in my career and grateful for all the teams that have given me the opportunity to represent the organization on and off the field.” When asked if he was disappointed that he didn’t get more chances in the majors, “I would be lying if I say no. But my dream became real once I made it.

“One thing I learned from playing this game is that you only can control what you do on and off the field, and not in the front office. I did my job great and to the best of my ability. But life goes on and now I find joy in teaching my son and other kids how to play the game. I was fortunate to learn a lot from some great players. So now I can teach what I learned.”

He added a gracious thank-you to his fans. “When you stop playing, most people forget about you, but the real fans don’t. So much love to all my fans that supported and followed me throughout my career. . .without them you ain’t nothing.”xvii

This biography has been adapted from the version originally published on the now-defunct website “Baseball in the Virgin Islands” in 1999, with revisions in subsequent years. Grateful acknowledgment to Calvin Pickering for his memories (telephone interview, June 25, 2012). Special thanks to the late Elrod Hendricks, Harry Shelton, Addie Joseph, and SABR member Andrew Martin for their contributions. Thanks also to Glen Byron for renewing contact with Calvin Pickering.

Notes

i This list includes Valmy Thomas, whose mother bore him in a hospital in Puerto Rico because she sought better medical care, but immediately returned home to St. Croix. It does not include Julio Navarro (born in Vieques, Puerto Rico; grew up on St. Croix) or Henry Cruz (born on St. Croix; moved to Puerto Rico with his family as an infant).

ii Andrew Martin, “Calvin Pickering: The Professional Hitter,” The Baseball Historian, June 28, 2011 (http://baseballhistorian.blogspot.com/2011/06/calvin-pickering-pofessional-hitter.html)

iii Joey Knight, “King First Baseman Pickering Emerging as ‘Jewel of the Isle,’” The Tampa Tribune, May 2, 1995, 5.

iv Richard Justice, “Orioles Like Their Prospects,” The Washington Post, February 25, 1999.

v In-person interview, Elrod Hendricks with Rory Costello, July 1999. Calvin Pickering, Facebook post, May 9, 2018.

vi Brant James, “Oriole Rides Winds of Change,” St. Petersburg Times, March 19, 1999, 14C.

vii Adam Adkins, “Baseball dreams,” Tampa Tribune, April 13, 2010.

viii Martin, “Calvin Pickering: The Professional Hitter”

ix Roch Kubatko, “Pickering, [Ryan] Minor sent to Triple-A,” The Baltimore Sun, March 19, 1999.

x Roch Kubatko, “[Brady] Anderson returns with bang,” The Baltimore Sun, March 29, 2000.

xi Kent Baker, “Pickering gains polish, loses girth,” The Baltimore Sun, June 29, 1998, 7D.

xii Roch Kubatko, “Pickering done for season,” The Baltimore Sun, July 22, 2000.

xiii Joe Strauss, “Longest summer weighs on Pickering,” The Baltimore Sun, September 26, 2000.

xiv Joe Strauss and Roch Kubatko, “Despite numbers, Pickering done in by crowd at first,” The Baltimore Sun, March 8, 2000.

xv David Boyce and Bob Dutton, “Pickering sent down to Omaha,” The Kansas City Star, April 22, 2005.

xvi Rich Elliott, “Bluefish Watch,” Connecticut Post, June 29, 2008.

xvii Martin, “Calvin Pickering: The Professional Hitter”

Full Name

Calvin Elroy Pickering

Born

September 29, 1976 at St. Thomas, St. Thomas (V.I.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.