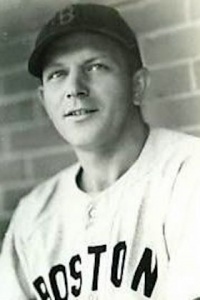

Dick Newsome

When Dick Newsome joined the Boston Red Sox in 1941, it might have seemed as though he would pair with Skeeter Newsome for a Southern radio program, “The Dick and Skeeter Show.” Or perhaps the “Heber and Lamar Hour.”

When Dick Newsome joined the Boston Red Sox in 1941, it might have seemed as though he would pair with Skeeter Newsome for a Southern radio program, “The Dick and Skeeter Show.” Or perhaps the “Heber and Lamar Hour.”

The two were both Southerners, but not related, and neither was related to Bobo Newsom, the only other major leaguer with a similar surname. All three careers overlapped. Both Skeeter and Dick were on the Red Sox from 1941-1943. Pitcher Bobo Newsom had been with Boston briefly in 1937.

Dick Newsome was a pitcher, too, a right-hander, born on December 13, 1909, as Heber Hampton Newsome. He was born in Ahoskie, North Carolina, and died there as well. His father, Wade, was a retail merchant who ran a general store. Wade and Sarah Janie (Mitchell) had four children – Alpha Marie, Heber, Lila King, and Irving P. He was always called “Dick” by his father; “Dick says that his mother occasionally calls him Heber but only occasionally. No one else does.”1

Young Newsome attended public school in Ahoskie, all the way through high school, and then went on to Wake Forest College for three years, where he also played football and basketball. He said that he “always had a desire to be a doctor,”2 but he was talented at baseball and it was too attractive a possibility to turn down when he was signed later in his college years and became part of the St. Louis Cardinals chain.

He put in four years, starting with the Piedmont League Greensboro Patriots in 1931 and winning quite a few games over the four years (40-29). He also pitched in Rochester, Elmira, and Springfield, Illinois. He never had a particularly good year and after a 9-13 season (with a 5.66 earned run average) with Greensboro again in 1934, he thought he wasn’t going anywhere. He quit baseball and started running a service station in North Carolina.3 He didn’t play at all in 1935.

But the Cardinals hadn’t forgotten him. Out of the blue he received a contract in the mail from the Pacific Coast League’s Sacramento Solons in early 1936. This was Double-A ball, a step up, but he was still inclined to ignore the letter. His five-month-old son, Dick Jr., wasn’t feeling well, and the family doctor had advised Newsome against taking his son on such a long trip. The bug was still in him, though, and it took a valet to talk him into it. It was quite a story.

“I had just received the new contract and a letter from Branch Rickey when a colored boy named Vernon Craig, son of our cook, Sally, who has been in our family ever since she was born, moseyed up to me. He had worked around the gas station for me. Seeing that I had something on my mind, he said, ‘Mistah Dick, what are you studyin’ ’bout?’

“I told him I had just received a contract from the Sacramento club, but didn’t think I’d accept it….

“‘Gee, Mistah Dick,’ he said ‘I shuah would like to go out to that there Pacific Cost. Why don’ you-all go out there and take me as your valet? You know I’m a handy boy to have around. I could drive the car for yoh, and I shuh can cook, or Sally Craig ain’t my ma.’”

Newsome said he talked it over with his wife (he had married Janet Murray Browne on Christmas Day 1932) and told her it looked like a promotion. She gave her consent.

“And that’s how I happened to land in Sacramento late in June with a colored valet. It caused a sensation in the league. Everywhere I went I was pointed out as the only ballplayer in organized baseball who had a valet. It really set me apart from the other players. I got it so often I liked it myself.”

That led to a little mischief. “When the business manager of the club asked me to fill out one of those Rickey questionnaires as to my hobbies and such, I went to town. They asked me what my favorite hobby was and I wrote in ‘Piano-Playing.’ The truth of it is I couldn’t play on the linoleum. But it traveled like wild fire and I was hailed as a sentimental Southern gentleman from Georgia who played ball for the fun of it. To a certain extent that was the truth, but there never was anybody who beat me to the office on the first and 15th for any pay check. I wasn’t too sentimental about it. It was rather lonesome for me, with the missus and Dicky back in No’th Ca’lina, but Vernon was always around, did the cooking, took care of the apartment and played a mean, if loud, piano.”4

It wasn’t that he had a large wardrobe. He said that at the time he had his “valet,” he had brought with him one coat, a couple pair of pants and two pairs of shoes.5 Some of the stories were exceptionally fanciful; the Los Angeles Times wrote that “he was reported to have been the owner of a rattlesnake which traveled around beside him on a leash!”6

Newsome arrived in time to get into 29 games and had a solid 3.53 ERA but was saddled with a 7-16 record. Management knew he’d pitched well, and brought him back again in 1937. This time, he brought his family – and Vernon Craig, who “continued to do the cooking, take care of the apartment and minded Dicky whenever Mrs. Newsome and I stepped out of an evening that I wasn’t playing ball.”7 Some of the newspapers started calling him “Marse Dick.”

Newsome worked in 30 games in 1938 and 33 in 1939, all for Sacramento. Craig had left him, heading off to New York after “Frank Doljack, an outfielder on our club, brought a colored fighter with him from Cleveland, where he lived.” The fighter was Lloyd Marshall, and “some slick fight managers from the East” talked Marshall into going to New York where they said they’d set it up for him to fight. Craig went with him as his “water bucket carrier.”8

Sacramento put Newsome on waivers after the 1938 season and he was claimed by the Portland Beavers. Longtime Oregonian sportswriter L. H. Gregory thought perhaps it was a mistake, or that they’d somehow tried to sneak him through waivers; in any event, Portland manager Bill Sweeney said, “You could have knocked me down with a breath when we got him as a gift by waivers. All that boy needs is work.”9

The only problem was that Newsome was thinking about retiring instead. He’d added a cleaning establishment to his holdings in Ahoskie, and didn’t think he was going anywhere in baseball. He reported late to Portland, arriving the night of March 28. He worked for the Beavers until July 6 when the San Diego Padres took him for the waiver price of $2,500. He arrived in San Diego two days later.. Henry Edwards wrote, “He never did get going and finished the season with only six victories as compared with fourteen defeats.”10 The Padres signed him to a 1940 contract in early September, nonetheless. For one reason or another, in Edwards’s words, “he made up his mind he would remain in condition all winter and report early the following year.”11

Something paid off. Newsome went 23-11 in 1940, with the best ERA of his career — 3.26. On April 25 he missed a perfect game in Oakland by just one hit, a second-inning single. There was one other incident earlier in the career worth noting – he struck out a batter, but the catcher failed to catch the ball. In fact, it bounced off the catcher’s chest protector out toward the mound where Newsome fielded it and threw out the batter as he ran to try and reach.

He was 21-10 at the time the Boston Red Sox purchased his contract on September 8, the agreement being he would report in 1941. The price was said to be $5,000 plus one player.12

Newsome joined the Red Sox for spring training – and was depicted in the March 6 Boston Herald with shortstop Skeeter Newsome when the two first met in Sarasota. The two were unrelated. Dick did not have an impressive spring; in June, Ed Rumill of Boston’s Christian Science Monitor wrote that “Newsome was probably the least impressive hurler in the Sarasota training camp this spring.”13 That was before he unveiled his knuckler.

Dick Newsome was a 31-year-old rookie in 1941 and had a great first season in the big leagues, beating every American League team at least once, and beating the White Sox seven times. He had opened the season on the Red Sox roster, but had been bought “on approval” from the Padres.

Newsome’s debut was on April 25, at Fenway Park against the visiting Philadelphia Athletics. He held Connie Mack’s Athletics scoreless on two hits through the first eight innings, giving up one lone run in the top of the ninth. It was a five-hit, 3-1 win, the one run coming on a ball that he himself might have fielded for a triple play, but the late-afternoon shadows at Fenway made the hard-hit ball tougher to field and it caromed off him past Skeeter Newsome at short and into left field. He had walked five batters, but he had worked quickly; the game lasted one hour and 46 minutes. His fastball wasn’t his best pitch; control was key, and the use of his curveball, sinker, and a knuckleball.

After spring training and his first two starts for Boston, he had shown manager Joe Cronin enough by the May deadline and on May 9, the team paid off the balance of the deal and obtained him outright. Even though he was defeated his second time out, giving up six earned runs in 4⅓ innings, the decision to keep him paid off – he won 19 games in 1941, seven more wins than anyone else on the second-place Red Sox. (Charlie Wagner and Joe Dobson each won a dozen.) Newsome’s earned run average was 4.13, almost the same as the 4.19 team average. He was 13-5 at Fenway. He was the league’s best rookie pitcher. The Boston baseball writers voted him the rookie of the year of the two Boston teams, the Braves and Red Sox.14

He won his first four decisions of 1942, and was described as “still the ace of the Red Sox pitching staff.”15 Neither 1942 nor 1943 proved to be nearly as successful as his rookie year. He won eight games each year, with 10 losses and 13 losses respectively. He couldn’t get his sinker to sink as effectively, Sox pitching coach Frank Shellenback told reporter Burt Whitman, who wrote that “Shelly…admits it was Dick Newsome’s loss of the sinker, at least, his failure to use it so well as in 1941, which caused Dick to have his below-par campaign.”16 After those first four wins, he lost his next three games in ’42. His ERA climbed to 5.01 in ’42, and was 4.49 in 1943, a year in which he was 1-8 by late July. He had a sore neck early on, and the Boston Globe ascribed some of his losses to Newsome being “unfortunate mainly in late innings.”17 He recovered belatedly, going 7-5 over the remainder of the season. He had two shutouts, a two-hitter, and a four-hitter, but it was as though if he wasn’t fully on, he had a good chance of taking the loss. He shut it down a couple of games before season’s end after suffering a chipped left ankle in the September 27 game.

Though the Sox signed him again for 1944, Newsome chose voluntary retirement on March 16, though without giving a reason. He had been called to a pre-induction physical with the Army that day, but was not taken.

Newsome turned his attention to farming, mostly corn and tobacco, and was involved in “extensive farming operations and related business,” and ran a cleaning and pressing enterprise, as well as serving as a director of two local banks, the Planter National Bank of Ahoskie and the Hertford County Savings and Loan Association.18 He also coached the local American Legion baseball team in Ahoskie.

Newsome was killed after a car crash on December 15, 1965. He suffered a “crushed chest” and died of “cardiac arrhtyhmia” (sic), after “deceased ran into back of parked vehicle.”19

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Newsome’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Henry P. Edwards, American League Service Bureau, press release for the newspapers of December 28, 1941.

2 American League questionnaire completed by Dick Newsome and on file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 He actually owned four service stations and ran a valet service in Ashokie. John Drohan, “Red Sox Can Thank Valet for Newsome,” Boston Traveler, April 26, 1941: 4.

4 Ibid. The subhead for Drohan’s story is a little shocking to see in a Boston newspaper of the day: “Darkey’s Offer to Be Handy Man Kept Pitcher from Quitting Game.”

5 Fred Knight, “Newsome, 10 Years in Minors Dons First Big League Suit,” Boston Herald, March 1, 1941 news story from clipping in Newsome’s Hall of Fame player file.

6 Layton Lewis, “Baseball’s Prima Donnas,” Los Angeles Times, August 1, 1937: 17.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid. For a little more on Newsome and Craig, see Will Connolly, “Jeeves, Fetch My Red Tie,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 31, 1936: 19.

9 L. H. Gregory, “Gregory’s Sports Gossip,” The Oregonian, November 6, 1938: 51.

10 Henry P. Edwards, American League Service Bureau, press release for the newspapers of December 28, 1941.

11 Ibid.

12 Alex Shults, “Deadline Tonight,” Seattle Daily Times, September 10, 1940: 19.

13 Ed Rumill, “Dick Newsome’s Knuckler Welcome Addition to Pitching Corps of Hustling Red Sox: Paces Red Sox Staff,” Christian Science Monitor, June 20, 1941: 16.

14 Associated Press, “Boston Scribes Select Newsome as No. 1 Rookie,” Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge), January 11, 1942: 22.

15 Ed Rumill, “Dick Newsome Still No. 1 on Joe Cronin’s Pitching Staff,” Christian Science Monitor, May 1, 1942: 14.

16 Burt Whitman, “Hughson’s Success Due to Change of Delivery,” Boston Herald, December 20, 1942: 78.

17 Melville Webb, “Dick Newsome, Sox Pitcher, Gets Draft Call,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1944: 11.

18 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1966.

19 Death certificate, North Carolina State Board of Health.

Full Name

Heber Hampton Newsome

Born

December 13, 1909 at Ahoskie, NC (USA)

Died

December 15, 1965 at Ahoskie, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.