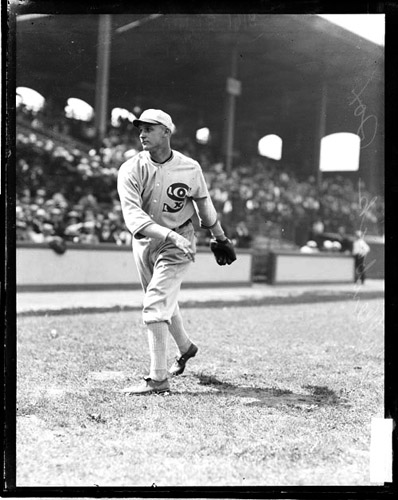

Frank Shellenback

Many believe that spitballer Frank Shellenback had his major-league career stolen from him when his key pitch was outlawed. In 1920 the National Commission did away with trick deliveries, including the spitball — and Shellenback’s team, the Chicago White Sox, for whom he had pitched in 1918 and 1919, didn’t list his name among those grandfathered to legally throw the pitch in the majors because he was then in the American Association. “That oversight prevented my ever getting another chance in the big leagues,” he later remarked.1

Many believe that spitballer Frank Shellenback had his major-league career stolen from him when his key pitch was outlawed. In 1920 the National Commission did away with trick deliveries, including the spitball — and Shellenback’s team, the Chicago White Sox, for whom he had pitched in 1918 and 1919, didn’t list his name among those grandfathered to legally throw the pitch in the majors because he was then in the American Association. “That oversight prevented my ever getting another chance in the big leagues,” he later remarked.1

For the very reason that Shellenback was an effective pitcher, he wasn’t welcomed back. But the Pacific Coast League allowed Shelly, as he was known in the clubhouse, to utilize his complete arsenal. He lasted another 19 years in the PCL and amassed 300 or more career victories in the minors. When he retired as a player after the 1938 season, he was the last legal spitball pitcher in Organized Baseball. (Burleigh Grimes was the last in the major leagues.)

There’s another side of the story. Shellenback grew up in Los Angeles and preferred the fine weather and leisurely pace of the West Coast to the predominantly Eastern major leagues. In fact, he asked the White Sox to trade him to a Pacific Coast League club even before the spitball was banned. He was also more than happy to stay close to his family. As Shellenback later professed, “I enjoyed my stay at Hollywood, was well paid and didn’t have to worry about moving my wife and six children from one city to another.”2

Yet while Frank was torn about his exclusion from the majors — he noted, “In a way that was a good break for me but in another way it wasn’t so good” — it was fortuitous that he parted ways with the White Sox when he did.3 At the age of 19, Shellenback played most of the 1918 season in Chicago, as pitchers Red Faber and Lefty Williams lost much of the year to World War I. Young Frank was friendly with and played beside Chick Gandil and Fred McMullin over the winter of 1918-19 in California. He was also well acquainted with fellow West Coast players Williams, Buck Weaver, and Swede Risberg. Had Shellenback stayed with the White Sox at the end of 1919, it’s conceivable that these associations might have led him down the path to expulsion from Organized Baseball in the wake of the tainted World Series.

Frank Victor Shellenback was born on December 16, 1898, in Joplin, Missouri. He was the youngest of five children born to John Albert Shellenback and Caroline A. Nolte. John had been born in Ohio in 1860 to parents from France. Baptismal records indicate that John’s surname was originally Schellenbach, which suggests a German heritage. This may be, since the family hailed from Alsace-Lorraine, a border region that often changed hands via war between France and Germany. John initially supported the family as a machinist but later found steady employment as an automotive mechanic. Caroline, or Carrie, was born in Illinois in 1867 to German-born parents.

By the time Frank was 10 years old the family had moved to Los Angeles. He attended Hollywood High School, where he played baseball, football, basketball, and rugby. The 1915 Hollywood High baseball squad, featuring Frank and his brother Paul, won the Southern California championship. That season Frank tossed a no-hitter against Los Angeles High. During the summer, the 16-year-old Shellenback started playing semipro baseball. He already stood out on the ball field with his baby face, blond hair, and stature (6-feet-2 and 189 pounds).

In the fall of 1915 Frank attended Santa Clara University, playing rugby and basketball for the school. Early the next year, however, he decided to enroll at Hollywood Junior College. He was immediately offered the position of assistant baseball coach. In March he was invited to spring training by Frank Chance, manager of the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels. He failed to make the team; instead, he ended up pitching in a mining league for a club near Ely, Nevada, where he also worked as an ore assayer. By July he had joined the Ruth, Nevada, club in a copper league, rolling off eight straight victories for that team.

At 18, Shellenback joined the White Sox for spring training in March 1917 in Mineral Wells, Texas. It was his first of three springs with the club. He claimed he learned the spitball from the White Sox pitchers. He recalled, “I just had to learn spitball pitching while I was with the White Sox because most of the club’s twirlers used the moist ball. Besides Eddie Cicotte, there were Red Faber and Joe Benz on the club using spitters.”4

In another version of his story, Shellenback said he asked Cicotte to teach him the pitch but was repeatedly rebuffed. So on the sly he examined the balls Cicotte used while warming up to study just what he did to them. On his own, he then tried to emulate Cicotte’s style. At first he threw the spitter with the full force of a fastball but the pitch never really broke; eventually, he learned to finesse the delivery to gain the maximum break. To add a little something to the pitch, Shellenback sucked on slippery-elm tablets and spat on the balls. However he learned the spitter, the fact is that he was throwing it before he joined the White Sox that first spring. Thus, he didn’t learn the pitch from Cicotte or any other Chicago pitcher.

White Sox coach Kid Gleason, a retired pitcher, didn’t care for the idea of such a young pitcher relying on the spitball. I.E. Sanborn wrote in the Chicago Tribune on March 24, 1917, “Gleason is working on Schellenbach [sic], the Los Angeles semi-pro, to convert him from a spitball to curve pitcher. The youngster is tall and has long arms able to pitch overhand, so that it looks to the batsmen as if the ball were coming off a hill top. Gleason figures he will be mighty effective with a curve, and it is seldom a pitcher can develop both a good spitter and a good curveball.”

In the end Gleason and manager Pants Rowland felt their rotation was solid enough, which it was. They sent the young Shellenback to Providence in the International League on April 15. In 24 games with Providence, he posted a 9-6 record. On August 16 the White Sox moved him to Milwaukee in the American Association; in eight games he won three and lost three. Over the winter he attended and played sports for Santa Clara.

On February 6, 1918, Shellenback re-signed with Chicago and joined the team for spring training. On April 28 the White Sox optioned him to Minneapolis. In three games there he notched a 1-2 record. A little more than a week later, he was recalled and made his major-league debut on May 8, in relief. He was wild that day, ceding five hits, two runs, and three bases on balls in four innings, but walked away with a 9-5 victory over Cleveland.

Chicago had won the World Series in 1917 with a solid rotation of Cicotte, Faber, Lefty Williams, and Reb Russell. They needed help in 1918, though; Faber was in the Navy and Williams was working in a Delaware shipyard. Owner Charles Comiskey sniped that Williams was a draft dodger, but Shellenback had no such worry. At 19, he was one of 63 major leaguers ineligible for the draft because of his age. The White Sox were happy to plug him into the rotation. In 28 games for the team he posted a 9-12 record with a solid 2.66 ERA, a mark lower than the league and White Sox’ average.

At the end of October, Shellenback enlisted in the aviation branch of the Army, passed all the required tests, and was assigned to the aviation school at Berkeley, California. He never got the chance to attend because the war ended in November. Instead, he spent the winter playing semipro ball for an oil company on the West Coast with Chick Gandil, Fred McMullin, Ivy Olson and Truck Hannah. Also playing in California that winter were three more White Sox teammates, Buck Weaver, Lefty Williams, and Swede Risberg. For years, Shellenback continued to play over the winter in and around Los Angeles. Often, he joined squads that played with and against major leaguers who drifted west after the season.

In March 1919, Shellenback, Gandil, and McMullin hopped a train for Mineral Wells and the White Sox’s spring camp. Kid Gleason was now manager. With the return of Faber and Williams, Shellenback was the odd man out, starting only four games through June 22. Four days later, Gleason inserted Dickey Kerr into the rotation. The White Sox were set for another pennant run — without Frank. On July 5 he made his final major-league appearance, pitching a scoreless inning in a 6-3 loss to Detroit. At 20, his big-league career was over, with 10 wins and 15 losses in 36 appearances. Shellenback was shipped from Chicago to Minneapolis on July 9 and in 20 games for Minneapolis he won seven games and lost three.

In January 1920, Shellenback informed the White Sox that he preferred to remain in California, close to home. He asked to be traded to the Vernon club of the Pacific Coast League. Instead, the White Sox sold him to Oakland on January 28. Shelly wasn’t happy about being peddled to Oakland because he wanted to play in the Los Angeles area. In March 1920 Oakland acquiesced, trading him to Vernon. In 35 starts there he posted an 18-12 record and 2.71 ERA, helping the club win the pennant.

On February 9, 1920, the major leagues formally banned pitchers from putting foreign substances on the baseball. No longer would they be allowed to apply saliva, rosin, talcum powder, paraffin, or any other substance before pitching. They were further prohibited from spitting on the ball or in their glove and from rubbing the ball on their person or in their glove. As conciliation to the game’s veterans, each club was permitted to name two men who could legally throw such pitches through the 1920 season. The White Sox naturally chose proven starters Eddie Cicotte and Red Faber as their designated two.

As it turned out, the majors ruled in December 1920 that 18 men would be granted dispensation to throw the spitball until their careers ended. Cicotte didn’t make that list; he was given his pink slip in the Black Sox affair. Shellenback didn’t either; he had been out of the majors for a year and a half and was no longer the property of a major-league club. Fortunately for Shellenback, the Pacific Coast League grandfathered him. He had to register every year with the league office, but would be permitted to throw the spitball in the minors. (A list of other PCL spitballers included Ray Keating, Al Gould, Buzz Arlett, Doc Crandall, Harry Krause, and Vean Gregg.)

If non-grandfathered spitball pitchers wanted to crack “The Show,” they had to revamp their game, as Heinie Meine and Hal Carlson did. Shellenback couldn’t or wouldn’t reinvent himself; thus, his return to the majors was effectively barred. Minor-league officials were a little more liberal. They permitted legally designated spitballers to change leagues. Also, quite a few of the 18 designated by the majors later pitched legal spitballs in the minors, among them Keating, Doc Ayers, Ray Caldwell, Dana Fillingim, Marv Goodwin, Burleigh Grimes, Clarence Mitchell, Jack Quinn, Allen Russell, and Allen Sothoron.

Over the winter and well into 1921, Shellenback played in the integrated California Winter League for Bob Fisher’s All-Stars, which included a slew of past or future major leaguers. They played black clubs like the Lincoln Giants and the Los Angeles White Sox, a club that featured Bullet Joe Rogan, Dobie Moore, Lem Hawkins, and others.

Shellenback went 18-10 for Vernon in 1921. As the season wore on he developed a bone chip in his elbow. Near the end of the season he had “a large piece of solid bone removed from his pitching arm.”5 After that, he had a tough time rounding his arm into shape every spring.

On January 17, 1922, Shellenback married Elizabeth H. Taylor, a District of Columbia native two years his junior. (They had six children beginning in 1925.) Shellenback’s arm still hadn’t recovered when spring training came in 1922. He appeared in only five games for Vernon before the club released him in early May. Shellenback ended up pitching for Fresno in the semipro San Joaquin Valley League. In late October, however, he was re-signed by Vernon.

Shellenback posted a 33-26 record for Vernon in 1923 and 1924, tailing off at the end of 1924. He started only 23 games that year because of injury. Robert E. Ray of the Los Angeles Times commented, “Shellenback went good at the start but was useless the last part of the year with a bad arm.” By October he was pitching for the semipro Hollywood Merchants. He also pitched for Hammond in the California Winter League. On December 3, Vernon traded Shellenback to Sacramento.

Shellenback turned in a mediocre 14-17 record for his new club in 1925. On October 18, Tony Lazzeri of the Salt Lake City Bees set a new mark in Organized Baseball with his 60th home run, an inside-the-parker off Shellenback in the seventh inning. Lazzeri did benefit from the pleasant Western weather, which permitted him to play in 197 league games that year.

Over the winter, Salt Lake City relocated to Hollywood, playing home games at the Los Angeles Angels’ park. Shellenback, a Los Angeles native, held out at the beginning of the year and asked to be traded to the relocated franchise after a season away from his hometown. On February 17, 1926, Sacramento relented and shipped him to Hollywood for pitcher Rudy Kallio, who (like Shellenback) amassed more than 500 decisions in the minors. Shellenback reached his tenth pro season in 1926, but he was still only 27 years old. He posted a 16-12 record in 29 starts. Over the next two seasons he added 42 more victories to his career total.

In 1929 Shellenback led the PCL in wins with a 26-12 record, even though his ERA rose to 3.98. He also chipped in a .322 batting average in 152 at-bats, with 12 home runs. During much of his PCL career, Shellenback was considered one of the best-hitting pitchers in the league, if not the best. For his career, he hit .269 in more than 1,800 minor-league at-bats, with 73 home runs. He won quite a few games with his bat; game recaps are strewn with his hitting contributions. He was often used as a pinch-hitter. After one game in 1933, the Modesto News-Herald exclaimed that Shellenback “proved again he is one of the league’s best pinch-hitters by hitting for the circuit with the bases loaded to score four of the Hollywood runs.”6 The postseason of 1929 was a prime example of Frank’s all-around efforts. As Hollywood defeated the San Francisco Missions in the playoffs, Shellenback won two playoff games and knocked three home runs, helping his club win the series in seven games.

In the early spring of 1930 Shellenback coached baseball at Loyola College in Los Angeles. Hollywood won the pennant again that season and defeated Los Angeles in the playoffs. Shellenback chipped in 19 wins. He had a tough time prepping for the season in 1931 because his arm wasn’t rounding into shape. He sought the advice and manipulating skills of bonesetter Doc Spencer. For the next several seasons, the pitcher spent part of his spring working with Spencer. In 1931 Shellenback won a career-high 27 games in 46 appearances, with a 2.85 ERA. He lost on May 3, ending a 16-game winning streak that had begun the previous season. He then immediately kicked off another 15-game streak.

In August 1931 Connie Mack of the Philadelphia A’s showed interest in acquiring Shellenback (the St. Louis Browns had also previously shown an interest). Mack contacted Hollywood owner Bill Lane, who was amenable. Mack then inquired with Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis concerning the pitcher’s eligibility under the spitball regulations. Landis probably could have easily granted a special exception, but instead ruled that his authority didn’t extend to decisions made before his hiring. Any lingering hopes Shellenback may have had about resuming a major-league career were quashed. Lane later declared that he could have gotten as much as $50,000 to $100,000 for the spitballer if Landis had ruled otherwise. (New York Giants manager Bill Terry also made a plea on Shellenback’s behalf in 1933.)

Shellenback held out for more money in 1932. The club was coming off back-to-back playoff appearances and he was luring the biggest crowds for the days he pitched. He and the Stars came to terms and Shellenback again led the league in victories (26, against 10 losses) and complete games (35). He won 21 games in 1933, bringing his total from 1928 through 1933 to 142 victories. That was his last 20-win season, though, and his ERA climbed to 4.53.

Shellenback’s glaring weakness was beginning to show. As one sportswriter noted, “His best offering is his spitter and when that is working he never has any trouble on the mound. But let his saliva slant go back on him and Frank is sunk. That’s why the Angels bumped him so vigorously the other day. His spitter wasn’t breaking and that settled matters then and there.”7

Shellenback won 14 games for Hollywood in 1934, topping Spider Baum as the all-time PCL victory leader. In the spring of that year, neuritis started to bother him. Shellenback was named manager of Hollywood in 1935, replacing longtime skipper Oscar Vitt. Although Frank was still capable of 14 wins, the team finished in last place. (That year he also appeared as a pitcher in the screwball comedy movie Alibi Ike, which was filmed at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles.)

In 1936 the Stars relocated to San Diego and were called the Padres. By the end of the previous season, the neuritis and persistent back pain had prevented Shellenback from taking his regular turn in the rotation. As the Padres’ player-manager from 1936 to 1938, he appeared in 15, six, and three games respectively. The club jumped to second place in ’36, missing the pennant by a game and a half. That club boasted Bobby Doerr, Vince DiMaggio, and rookie Ted Williams.

Williams was especially fond of Shellenback, declaring in his autobiography My Turn At Bat, “He was a wonderful, wonderful man, a man I respected as much as any I’ve known in baseball.”8 Doerr also benefited from his manager’s skill with young players — though he had to be careful about his throws to first when Frank was pitching. He would sometimes grab the slick spot on the ball after fielding a grounder.

San Diego finished in third in 1937, but proceeded to win the PCL championship in the playoffs. However, the club fell off to fifth place in ’38. On October 2, Shellenback was unceremoniously fired. Bill Lane, who had been his employer since 1926, sent assistant Spider Baum with a pink slip that tersely read, “Frank Shellenback released unconditionally, W.H. Lane.”9

Shellenback also retired as a player. He appeared in 640 minor-league games, amassing a 316-191 record, approximately 360 complete games, and 4,500 innings pitched. His 296 wins in the Pacific Coast League are the most by any pitcher in one minor league; he was one of the first five PCL players elected to the league’s Hall of Fame in 1943. Of minor note, he used only one glove during his entire PCL career.10

A month after his release, Shellenback returned to the majors at long last, signing with the St. Louis Browns as a pitching coach for 1939. After the season he asked out of his contract with St. Louis to become the pitching coach for the Boston Red Sox, reuniting with quite a few of his minor-league charges. The Shellenback family left Los Angeles and settled in the Boston area, where they remained. Shellenback coached for the Red Sox from 1940 through 1944 and then joined the Detroit Tigers as a New England scout for 1945. In 1946 he became the Tigers’ pitching coach, lasting for two seasons. Each year he oversaw the team during manager Steve O’Neill’s brief hospital stints.

In 1948 Shellenback became manager of the Minneapolis Millers in the New York Giants’ organization. He managed the club to a 31-33 record before turning it over to Billy Herman because of health issues; his doctor insisted that he take time away from the game. Shellenback returned in 1949 as a roving pitching coach for the Giants, impressing manager Leo Durocher. After the season Durocher added him to his major-league staff. Durocher held Shellenback in high regard, once commenting, “I take Shelly’s word on anything about pitching. If he says a fellow is ready, he’s ready. He’s the best. He has a genius for spotting when a pitcher is doing something wrong. I may sense it. But Shelly sees it immediately — and has the answers.”11

Shellenback remained in this capacity through 1955, including World Series appearances in 1951 and 1954, until Durocher left the organization. At least once Frank filled in for the manager while Durocher was visiting his sick mother in September 1953. Shellenback was one of the leading authorities in the game when it came to the spitball. He was often quoted as describing its effectiveness and discussing its proper use. Throughout Shellenback’s stint with the Giants, opponents accused the club of being one of the foremost abusers of doctoring baseballs.

Shellenback continued in the Giants organization as supervisor of minor-league personnel from 1956 to 1959 and as a part-time Eastern scout and traveling coach from 1960 to 1969. During this time, the spitball was a hot topic in the press, in the clubhouse, and on the field. Shellenback fueled the debate by helping Bob Shaw and Gaylord Perry develop and gain control of the wet one. Accusations flew in 1965 as the Giants challenged for the pennant, though the Dodgers edged them by two games.

On August 17, 1969, Shellenback died at his home in Newton, Massachusetts, at the age of 70. He had been ill off and on, but death came unexpectedly. He was interred at Newton Cemetery. His nephew Jim Shellenback pitched for four teams in the majors from 1966 to 1977.

Baseball analyst Bill James said, “Frank Shellenback may have been the best pitcher in the history of the minor leagues.” Other pitchers have posted more victories — but none did it at the same level as Shellenback. Aside from his 36 games in the majors, his entire career in Organized Baseball was spent at the top tier of the minors. The last legal spitballer in Organized Baseball attributed his success to his bread-and-butter pitch, declaring, “I wouldn’t have lasted as long as I did if it weren’t for the spitter.”12

Last updated: January 01, 2021 (ghw)

A version of this biography appears in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015), edited by Jacob Pomrenke. It also appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Beverage, Richard, The Hollywood Stars (Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2005).

Halberstam, David, The Teammates (New York: Hyperion, 2004).

James, Bill, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003).

McNeil, William, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

Porter, David L., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball (New York: Greenwood Press, 1987).

Szalontai, James, Close Shave: The Life and Times of Baseball’s Sal Maglie (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

Williams, Ted, and John Underwood, My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988).

Zingg, Paul J., and Mark D. Medeiros, Runs, Hits, and an Era: The Pacific Coast League, 1903-58 (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Newspapers: Atlanta Daily World, Chicago Tribune, Christian Science Monitor,

Jefferson City (Missouri) Daily Capital News, Fairbanks (Alaska) Daily News-Miner,

Fitchburg (Massachusetts) Sentinel, Fort Wayne (Indiana) Journal-Gazette, Galveston (Texas) Daily News, Hartford Courant, Indiana (Pennsylvania) Evening Gazette, Iowa City Citizen, Le Grand (Iowa) Reporter, Lima (Ohio) Daily News, Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Reporter, Los Angeles Times, Modesto (California) News-Herald, Benton Harbor (Michigan) News-Palladium, The New York Times, Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, Racine (Wisconsin) Journal News, Salt Lake Tribune, San Mateo (California) Times, Valparaiso (Indiana) Vidette-Messenger, Waterloo (Iowa) Times-Tribune.

Ancestry.com

Baseballlibrary.com

Baseball-reference.com

Notes

1 Los Angeles Times, November 4, 1934.

2 Atlanta Daily World, July 26, 1960.

3 Los Angeles Times, November 4, 1934.

4 Los Angeles Times, August 17, 1930.

5 Chicago Tribune, October 10, 1921.

6 Modesto News-Herald, July 21, 1933.

7 Los Angeles Times, April 15, 1933.

8 Ted Williams and John Underwood, My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 39.

9 Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1938.

10 See, for instance, the Benton Harbor (Michigan) News-Palladium, May 20, 1936.

11 New York Times, May 21, 1954.

12 Atlanta Daily World, July 26, 1960.

Full Name

Frank Victor Shellenback

Born

December 16, 1898 at Joplin, MO (USA)

Died

August 17, 1969 at Newton, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.