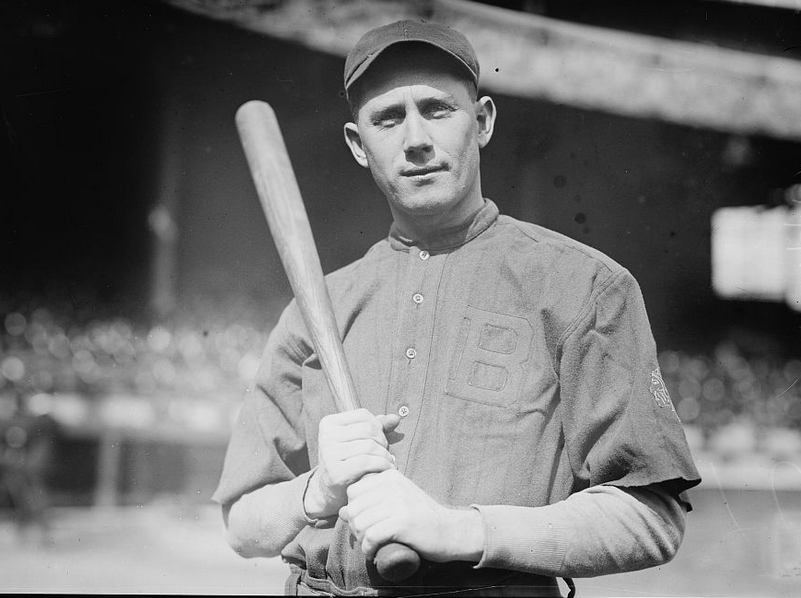

Ted Cather

A baseball player fighting during a game isn’t that unusual. A player fighting twice in less than a year is probably a little rarer. Fighting twice in less than a year with your own teammates – during a game – may be unprecedented. But that’s exactly what happened to St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Ted Cather. The resulting fallout led to him becoming a Boston Brave and helping the Miracle Braves to the National League pennant in 1914.

A baseball player fighting during a game isn’t that unusual. A player fighting twice in less than a year is probably a little rarer. Fighting twice in less than a year with your own teammates – during a game – may be unprecedented. But that’s exactly what happened to St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Ted Cather. The resulting fallout led to him becoming a Boston Brave and helping the Miracle Braves to the National League pennant in 1914.

To the Cardinals and their future Hall of Fame manager Miller Huggins, one incident may have been an accident but twice was certainly a trend. So when Cather got into a fistfight with pitcher Dan Griner during a game in late June of 1914, Huggins had enough of his streak-hitting player and Cather was traded to the last-place Boston Braves.

Little did Huggins know that the trade would help propel the Braves from last to first as Cather, as a right-handed-hitting platoon player, was one of several pieces that fell into place for the Miracle Braves. In the 50 games the 5-foot-10, 178-pound Cather played for the Braves after the trade, against almost exclusively left-handed pitching, he hit .297 with 27 RBIs. Sporting Life took notice after the season in a review of the Braves’ incredible run when it wrote that the team “was considerably strengthened by the acquisition.”1

It was quite a turn of events for Cather who, at the end of the 1913 season wasn’t even sure if he would be in the major leagues in 1914, let alone play in and win the World Series.

Theodore Physick Cather, born on May 20, 1889 in Chester, Pennsylvania, was the youngest of three sons born to Samuel and Mary Cather.2 He was named after his maternal grandfather, Theodore Physick.

His father, Samuel, who was a carpenter, was of Scottish descent and pronounced his last name “Car-ther.”3 Both parents had been born on Maryland’s Eastern Shore but had moved to Chester, 15 miles south of Philadelphia on the Delaware River, before Ted’s birth.

By the time Ted had turned 11, his father was no longer living with the family in Chester but had moved to Rising Sun, Maryland. Ted lived with his mother, two older brothers, his grandmother, and an uncle. By 1902 he was getting noticed as a pitcher while playing for the Larkin School team.4 As he got older, he found himself pitching for local semipro teams.5

Before he got his break in Organized Baseball, Cather worked many jobs to help his family. He was a plumber, barber, druggist, roller-skating instructor, and an asbestos coverer in a locomotive works.6

By 1909 Cather was a pitcher of some note in the Philadelphia semipro community. His break came that year when the Johnstown Johnnies of the Class B Tri-State League came to Chester to play a game. Pitching for the Delaware County All-Stars, Cather shut out the Johnnies. Curtis Weigand, manager of the Johnnies, signed him to a contract soon after the game.7 He made a big splash right away, pitching a two-hitter against Lancaster on May 4.8

Weigand also noted Cather’s ability to hit the ball and played him in the outfield on occasion.9 Cather played with the team until July 3. It’s not clear whether he was let go or left the team on his own.

But he must have made an impression because Lancaster manager Marty Hogan signed him in January for the 1910 season.10 Cather responded with a fine season in which he went 20-9, finishing second in the league in wins. It was a good year for Cather: Immediately after the season he was sold to Toronto of the Eastern League11 and then he was married on November 1 to Martha Worshaw. At the age of 21, Cather’s life seemed to be heading in the right direction.

Cather started the season at Toronto in 1911. The Harrisburg Patriot reported early in the season that he was “doing good work on the mound”12 but by midseason his record was only 3-4 and Toronto, with a chance to add former major-leaguer Les Backman, demoted Cather to Troy of the Class B New York State League.13 Cather finished at Troy with a 6-7 record. What was once a promising career seemed to be headed in the wrong direction.

But just as in 1910, another opposing team picked him up. This time it was the Scranton Miners of the Class B New York State League. Instead of just pitching for the Miners, Cather was called on to both pitch and play the outfield. In his first game as a pitcher, he took a no-hitter into the ninth inning and went 4-for-4 at the plate with a triple.14 He played in 80 games for the Miners, 49 as an outfielder.

Cather ended the season batting .312, a figure that caught the notice of the sixth-place St. Louis Cardinals. Looking to find any kind of hitting, the Cardinals drafted Cather from Scranton at the annual meeting of the National Baseball Commission on September 16.15 A week later he made his major-league debut in Brooklyn in a 7-2 Cardinals’ loss to the Superbas.

Playing in the outfield, Cather was red-hot in the five games he played in, batting .421. The buzz began to grow in the offseason that Cather would become a key player for the Cardinals in the 1913 season.

By the time Cather arrived in Columbus, Georgia, for spring training in 1913, he was already penciled in by the press as an extra outfielder on the big-league roster.16 Cather played well enough to make the roster though he was still shaky in the field. But his hitting won him a spot going north with the big club.

For years after, Huggins was credited with moving Cather permanently from pitcher to everyday player.17 And while Huggins didn’t pitch him (except for one-third of an inning in 1913 in mop-up relief), he hardly can be given credit for seeing Cather’s ability at bat. As far back as his first season in Johnstown, Cather had played some games in the field. His 1912 season proved that he was a better everyday player than a pitcher.

Cather started the season on the bench but soon replaced Jimmy Sheckard in the outfield.18 But just as soon as Cather was getting accustomed to starting, on June 13 he broke his arm when he crashed into wall making a catch on a Gavvy Cravath fly ball. He held onto the ball but was out for about a month.19

He made it back onto the field by mid-July and started the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Giants on July 17. In the third inning the Giants’ Larry Doyle hit a short fly ball between Cather and Lee Magee. The papers at the time said that it fell in between the two.20 Magee remembered it three years later as the two colliding on a ball that Magee had called.21

As the two ran in at the end of the inning, they began jawing at each other. According to the papers, Cather swung and hit Magee with a punch.22 As with almost any baseball fight, chaos ensued. Umpire Malcolm Eason and several Cardinals players moved in to break up the melee. Cardinals first baseman Ed Konetchy was punched breaking up the fight.23

The New York Times wrote, “The fight stopped the game for a time and the spectators who tried to jump over the boxes into the field [to get a better view of the fight] were turned back by the police.”24

When peace was brought to the situation, Eason threw both players out of the game. So the fight wouldn’t continue in the locker room, 6-foot-5, 228-pound backup catcher Larry McLean was sent with the two to make sure there was no more bloodshed.25

National League President Thomas Lynch fined each player $25. He said that the incident “warranted suspension” but that because St. Louis had so many injuries, he wouldn’t punish them more than the fine.26

A little over two weeks later, Cather and Magee were pictured on the front page of The Sporting News. Both were in uniform with boxing gloves on. The picture was entitled “Battling Magee and Kayo Cather.” Both players were smiling as The Sporting News made light of their battle.27

Despite Cather’s problems with his fellow outfielder, the newspapers reported that he was making progress as an outfielder.28

A wire service story with the headline “Teddy Cathers [sic] Makes Good” was carried in many papers throughout the country. The story related how the Cardinals were turning many of their players into outfielders in the hopes of bettering the team.29 And Cather was one of their latest successful projects.

While Cather’s fielding was getting better, his hitting was not. He was suffering through a long slump. Then on September 1, he broke his leg sliding into second base. His season was over.

Having batted just .213 for the season, Cather was released, along with catcher Skipper Roberts, to Indianapolis on September 12. Cather was facing what could have been the end of his major-league career. His personal life was in a state of flux as well. After the season, he started divorce proceedings against his wife, Martha, on the grounds of unfaithfulness. At the time of the divorce filing, he didn’t even know where she was living.30 She had taken their 3-year-old son as well, which led to one of the more bizarre events in Cather’s life.

While driving through Camden, New Jersey, on December 15, Cather saw his mother-in-law walking his son down the street. He stopped the car, jumped out, and grabbed the boy from the woman. His mother-in-law screamed, then ran to the car and interlocked her arms around the steering wheel.31

Cather attempted to drive the car but had trouble without hurting the woman.32 As a large crowd gathered, he handed his son over to the woman and drove away.33 The story made national news.

But in 1914, luck changed for Cather. The Indianapolis team had a change of heart, decided it didn’t want Cather, and returned him to the Cardinals. With the Federal League making raids on the major leagues, the Cardinals needed Cather to fill in as an extra outfielder.34

The Federal League also was interested in Cather. Otto Knabe, manager of the Baltimore Terrapins, talked to Cather about playing for his team.35 But in the end, Cather went to camp with St. Louis and made the squad as one of only two right-handed-hitting outfielders. The other was Cather’s former fighting partner, Lee Magee.36

Cather started the season on fire. He was among the league leaders in hitting. Toward the end of May, Cather was hitting .352, tied for third in the National League.

But the events of May 27 signaled the beginning of the end of Cather’s tenure with the Cardinals. During a 7-4 home loss to the Boston Braves, Cather fought pitcher Dan Griner after Griner became incensed over a play Cather made in the outfield. The two fought long enough for the 6-foot-1, 200-pound Griner to open up a gash on Cather’s chin that required five stitches to close.37 The teammates were fined $100 apiece by Huggins and left home as the team traveled to Chicago.

A month later, despite his hot bat off the bench, Cather was traded with infielder-outfielder Possum Whitted to the Braves for pitcher Hub Perdue. Perdue was 2-5 with a 5.82 ERA for Boston when he was traded, yet the Cardinals were willing to give up both Cather and Whitted for him.

Four years later Miller Huggins explained, “I needed a pitcher badly.” He “discovered that Hub Perdue might be had. I was glad to get him as he always pitched great against my club.”38

After two fights with his own teammates, it was clear to the press that Cather “could not get along very well with several of the players.”39 Baseball Magazine wrote that he was “condemned at St. Louis as too crude” and was just “tossed in as part of a midsummer trade for Hub Perdue.”40

Whatever the reason for the trade, Cather paid off for Braves manager George Stallings. Playing left field when the Braves opposed a left-handed pitcher, Cather hit .295 in 41 games from July 4 to the end of the season.41 The team turned around shortly after the trade and played great baseball, rising from last place to win the pennant.

In a retrospective after the season, William A. Phelon in Baseball Magazine wrote that the trade “is often spoken of as something which counted heavily in the winning of the flag. It did and it didn’t. As far as any change in the playing array was concerned it made little difference.”

He went on to note that “Cather was little used” but “Whitted made himself a regular outfielder toward the end of the season.” But he did believe the trade was responsible in part for the Braves’ turnaround. “Where the trade made the most real difference was in the way it woke up the fellows who still clung to the payroll and made them hustle from that time on until the end,” Phelon wrote.42

The nationally syndicated columnist “Monty” had a different take: Stallings “takes boobs and turns them into star ball players.” That was “9/10 of the reason” why Braves played so well.43

Whatever effect the trade had, the Braves turned their season around and won the National League pennant. Their reward was to play the powerful Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

The Braves continued their amazing play, sweeping the Athletics in four games. Cather played in one game in the Series, Game Two. Batting third in the lineup, he was 0-for-5 against future Hall of Famer Eddie Plank as the Braves eked out a 1-0 win.

After the World Series Cather was the toast of his hometown, Chester. October 22 was declared “Cather Day.” The day included a parade and banquet. The parade consisted of baseball teams from throughout the area.44 At night, 250 people attended a banquet at the Masonic Hall.45 Cather, in a brief speech, “predicted that the Braves would carry off both pennants again in 1915.”46 If the Braves would win the pennant in 1915, it would be without Cather, however.

Spring training was a highlight of Cather’s 1915 season. After catching a train with a bunch of his teammates from Chester to Macon, Georgia, Cather found himself being tried out in the infield by Stallings. Stallings needed some depth in the infield and felt that Cather had the “natural grace and intelligence” to be a good utilityman.47

Stallings worked Cather at both shortstop and third base but mostly at third. Third base had been a question mark for Stallings even in 1914, with five players holding down the position at one time or another during the season. Charlie Deal, who had played the most games at the position in 1914, had jumped to the Federal League. With Red Smith getting the starting nod, it fell to Billy Martin, who had played all of one game at third, to be Smith’s backup for the coming season. But Martin had been injured early in training camp and Stallings decided to move Cather from the crowded outfield battle to the infield.48

None other than Grantland Rice noticed that “Cather is playing fine ball at third, fielding well and batting up with the club average and a few points higher.”49 Cather’s hometown paper, the Chester Times, went even further about “Lucky Ted,” writing that he “may get a regular berth.”50

But when the season began, Cather again found himself on the bench, starting only against left-handed pitchers. He struggled, batting .206 in 40 games. He did, however, hit the only two home runs of his major-league career. Both, curiously, came off future Hall of Famer Rube Marquard in different games.51

But it wasn’t enough for Cather to keep his spot on the roster as the Braves floundered. On July 12 he played his last major-league game. With the Braves’ record at 32-41 after a doubleheader sweep by the St. Louis Cardinals, Stallings released Cather, along with fellow outfielder Larry Gilbert, to Toronto of the International League.52

Though Cather never played in another major-league game, the release was far from the end of his baseball career. For the next ten years he played at the highest level of the minor leagues, just a short jump to the majors.

Cather played for less than a month before Toronto released him. On August 10 he signed with Jersey City, where he finished out the season. His combined average was .284.

Soon after the season was over, the Braves, who still had a string on Cather, traded him, outfielder Herbie Moran, and catcher Bert Whaling to Vernon of the Pacific Coast League for promising outfielder Joe Wilhoit.53

While Cather’s professional career was in disarray, he had managed to get his personal life under control. After finally being granted a divorce from his wife, he married Ida E. Dodge, a 28-year-old nurse. They moved to Charlestown, Maryland, at the head of Chesapeake Bay, a town he would live in for the rest of his life.54

Cather’s baseball odyssey continued in April 1916. Vernon sold him to Montreal along with infielder Billy Purtell and Herbie Moran.55 So Cather headed to Hackettstown, New Jersey, where the Royals had their training camp. The Royals were interested in trying Cather at second base.56

All of the changes of teams left Cather in a strange position of being paid by three different clubs in 1916, though Organized Baseball’s National Commission had to step in to ensure that he got his full amount.

Cather’s release from Jersey City to Vernon was brought about by the Boston Braves, who had entered in an agreement with Vernon by which that club would pay Cather $325 a month and Boston would make up the rest of his salary. But Vernon decided it couldn’t pay Cather that much, and sent him to Montreal, which would pay him $250 a month. The National Commission ruled that Vernon had to pay the extra $75 a month.57

Cather got into 83 games for Montreal, playing solely in the outfield and batting .274. He returned to Montreal for 1917 and didn’t fare much better. He batted only .240 in 87 games. But he did manage to supplement his salary by hitting the Durham Bull, Blackwell Tobacco Company’s iconic ad for its popular smokeless tobacco product, which adorned the outfield walls of some of the parks in the International League. If you “hit the bull,” it was worth $50. Cather did it three times during the season.58

After the season the International League ousted Montreal, Richmond, and Providence in an effort to cut travel costs. Binghamton, Jersey City, and Syracuse were added to the league.59 As a result, Cather was a free agent. He was snapped up by Rochester manager Arthur Irwin and went to training camp.60 But there was a dispute over who actually owned the rights to Cather and eventually his contract was awarded to Newark.61

For the first time in his career, Cather was a regular and played injury-free. He played in all 127 games for the Bears, batting .278 and playing mostly in the outfield.

In 1919 Cather’s batting average dipped to .226 in 105 games. After the season he was looking for a new team. When none came knocking, Cather played in an industrial league in Ohio for the 1920 season.62 But in 1921, Oakland Oaks owner Cal Ewing signed him to a contract that led to Cather’s best playing days.63

For the next four-plus years, Cather was a mainstay in the Oaks’ lineup. In his first season, 1921, he was mostly used as a utility player, getting into 63 games and batting .217. However, for the next couple of seasons, Cather improved on the previous season’s performance, culminating in his best season as a pro in 1923. Playing in 184 games that season, Cather led the Oaks in batting average (.344), hits (269), and doubles (46), and was second on the team in home runs (10) and triples (11).

While 1923 was the high mark professionally for Cather, personally it was a low mark as he filed for divorce from his second wife, saying she had struck him.64

The 1924 season was another good one for Cather; he batted .300 in 173 games. But the 35-year-old player was noticeably slowing down. The Oakland Tribune wrote that he wasn’t a “good ground coverer” in the outfield.65

Cather started the 1925 season off poorly with the Oaks. By the end of May, he was hitting only .220.66 On June 14 the Oaks released him so they could sign Chicago Cubs castoff Hack Miller.67 Sacramento picked up Cather for some of the remaining season but cut him loose after it.

The next year, 1926, became one of new starts for several reasons for the 37-year-old Cather. First, his third wife, the former Clara “Carrie” Bishop of Wilmington, Delaware,68 gave birth to his second child, a daughter named Mary Theo Cather.69

Second, after turning down and offer to become player-manager of the Logan Collegians of the Utah-Idaho League,70 Cather returned home to Maryland and joined the Easton Farmers of the Class D Eastern Shore League. Buck Herzog, manager of the Farmers, told the press that Cather was “setting a fine example” and had been given the nickname Old Folks by his teammates.71 He played in the Eastern Shore League for two seasons. In 1927 he briefly succeeded Herzog as manager of the Farmers. He also spent time with the Cambridge Canners of the ESL. At the age of 38 he retired after the 1927 season, going out with a flourish: He had batted over .300 in both seasons.

By the time Cather retired, he was well established as a businessman in Charlestown. He owned the general store in town and became Charlestown’s postmaster.72 He built and operated 10 rental cabins for summer tourists along Chesapeake Bay.73 Later he became a member of the town commission. He spent the rest of his life in Charlestown.

On March 3, 1945, Cather went into the hospital for an abdominal abscess that turned out to be appendicitis.74 While recovering in Union Hospital in Elton, Maryland, on April 9, Cather died of a coronary thrombosis at the age of 55. He was buried in Charlestown Cemetery.75

This biography is included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, October 17, 1914

2 Baltimore City Health Department Certificate of Death

3 Richmond News Leader, October 31, 1991

4 Chester Times, October 8, 1914

5 Chester Times, October 8, 1914

6 Chester Times, March 26, 1913

7 Undated article in Cather’s Hall of Fame file

8 Williamsport Gazette & Bulletin, May 7, 1909

9 Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1909

10 Trenton Times, April 4, 1910

11 Reading Eagle, October 4, 1910

12 Harrisburg Patriot, April 26, 1911

13 Sporting Life, July 1, 1911

14 Chester Times, May 13, 1912

15 Sporting Life, September 21, 1912

16 Washington Post, March 10, 1913

17 Sporting Life, October 17, 1914

18 Chester Times, February 2, 1914

19 Undated article in Cather’s Hall of Fame file

20 Syracuse Herald, July 18, 1913

21 Brooklyn Eagle, July 23, 1916

22 Syracuse Herald, July 18, 1913

23 New York Times, July 18, 1913

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Alton (Illinois) Evening Telegram, July 19, 1913

27 The Sporting News, August 7, 1913

28 Duluth News-Tribune, August 4, 1913

29 Postville (Iowa) Review, August 22, 1913

30 Chester Times, October 26, 1913

31 Sporting Life, December 20, 1913

32 Duluth News-Tribune, December 21, 1913

33 Philadelphia Inquirer, December 16, 1913

34 Baseball Magazine, February 1915

35 Chester Times, February 2, 1914

36 Sporting Life, March 2, 1914

37 Pittsburgh Press, May 29, 1914

38 Fort Wayne News & Sentinel, April 16, 1918

39 Chester Times, October 8, 1914

40 Baseball Magazine, December 1914

41 Baseball Digest, October 1964

42 Baseball Magazine, February 1915

43 Miami Herald Record, September 10, 1914

44 Philadelphia Ledger, October 22, 1914

45 Chester Times, October 17, 1914

46 Philadelphia Inquirer, October 23, 1914

47 Boston Journal, March 13, 1915

48 Boston Journal, March 24, 1915

49 Washington Post, March 20, 1915

50 Chester Times, March 5, 1915

51 Bob McConnell and David Vincent, SABR Presents the Home Run Encyclopedia. (New York: Macmillan, 1996), 364.

52 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 14, 1915

53 Ogden (Utah) Standard, November 27, 1915

54 Chester Times, September 22, 1915

55 Binghamton Press, April 4, 1916

56 Montreal Daily News, April 21, 1916

57 Wilkes-Barre Times, July 1, 1916

58 Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, July 20, 1917

59 William Brown, Baseball’s Fabulous Montreal Royals. (Montreal: Robert Davies Publishing, 1996), 24.

60 Wilkes-Barre Times, April 27, 1918

61 Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, May 20, 1918

62 The Sporting News, February 17, 1921

63 San Francisco Chronicle, February 5, 1921

64 Oakland Tribune, February 9, 1923

65 Oakland Tribune, April 3, 1924

66 Oakland Tribune, May 24, 1925

67 The Sporting News, June 18, 1925

68 Undated article in Cather’s Hall of Fame file

69 Richmond News Leader, October 31, 1991

70 Ogden Standard, March 30, 1926

71 Undated article in Cather’s Hall of Fame file

72 Undated article in Cather’s Hall of Fame file

73 Richmond News Leader, October 21, 1991

74 Baltimore City Health Department Certificate of Death

75 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 65.

Full Name

Theodore Physick Cather

Born

May 20, 1889 at Chester, PA (USA)

Died

April 9, 1945 at Elkton, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.