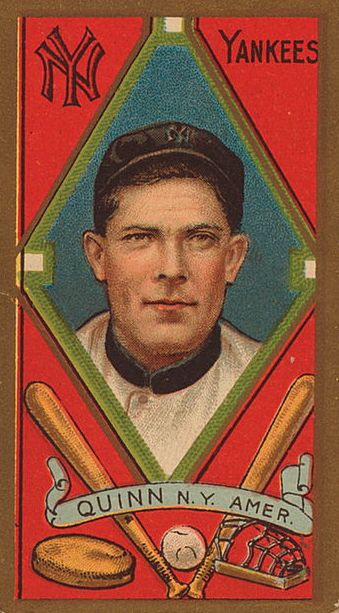

Jack Quinn

He won 247 games in his 23 seasons in the major leagues, plus dozens more in the minors and as a semipro in a pitching career that spanned more than 30 years. Yet we do not know for certain when or where he was born, the national origin of his forebears, or even his birth name. We know him as Jack Quinn, and the reference books agree that he was born John Quinn Picus, which very likely was not the case. Among four editions of the Baseball Encyclopedia, no two of them gave the same birth date and birthplace. Jack Quinn’s personal life was a mystery and he liked it that way.

He won 247 games in his 23 seasons in the major leagues, plus dozens more in the minors and as a semipro in a pitching career that spanned more than 30 years. Yet we do not know for certain when or where he was born, the national origin of his forebears, or even his birth name. We know him as Jack Quinn, and the reference books agree that he was born John Quinn Picus, which very likely was not the case. Among four editions of the Baseball Encyclopedia, no two of them gave the same birth date and birthplace. Jack Quinn’s personal life was a mystery and he liked it that way.

Depending upon which source one believes, the pitcher known as Jack Quinn was born on July 5, 1883, or 1884 or 1885. As an infant, he emigrated with his family to southwest of Wilkes-Barre, but whether it was Janesville, Jeansville, Jeanesville, Hazleton, Mahanoy City, Gorman’s, St. Clair, or some other coal mining town, is a matter of dispute. The first two places can probably be ruled out, Janesville being in the wrong part of the state and Jeansville most likely being a misspelling of Jeanesville.

As for his age, it was a popular topic of speculation among baseball writers as Quinn was getting along in years. Many were of the opinion that he was at least three or four years older than the age given in most record books. Quinn did nothing to end the controversy. “I’ll tell my age when I quit,” he once said. “Nobody’s going to know before that.”1 Eventually, the old spitballer did retire, but he reneged on his promise and even then he did not reveal his true age.

He told another interviewer, “I’m not as old as they try to make out….Some of these newspaper fellows had me forty years old ten years ago. I’d be wearing long white whiskers like Santa Claus if I had kept pace with all the dope that’s been written about my age. I’m old enough, and there’s no argument on that point. But why confine me to the boneyard before my time?”2

The assertion in his Sporting News obituary that Quinn had served in the Spanish-American War is probably incorrect.3 The most likely date of his birth was July 5, 1883. All references to his age at the time of various accomplishments will be based upon that assumption.

John Kieran of the New York Times wrote that Quinn was called a Welshman, a Pole, an Irishman, and an Indian, among other things.4 Greek, Slovak, and French can be added to the mix. Quinn was sometimes called an Irishman, probably by those who thought Quinn was his real name. Usually he was said to have been of Welsh or Polish extraction, a logical guess since most of the miners in the area were of such lineage, but Picus certainly is not a Welsh name. With tongue in cheek, Kieran reported that the pitcher was actually of Russian ancestry and that the family name was originally Pajkosz5 He based this on a letter from an old resident of Mahanoy City, who said that his father was a grocer in that town, and in his daily rounds with horse and wagon he delivered groceries to the parents of Jack Quinn, who lived in Gorman’s, a tiny hamlet on the outskirts of Mahanoy City. He further stated that Jack was born in Gorman’s, that he was of Russian parentage, that he was christened in the Russian church at Shenendoah, as there was no Russian church in Mahanoy City and no church of any kind in Gorman’s. The oldtimer said that the family’s name was Pajkosz, pronounced Pie-kosh. Lee Allen, the baseball historian, wrote that he was able to find a baptismal certificate showing that our hero was born at Jeansville [sic] on July 5, 1884. He went on to state that Picus is a truncated form of the Polish name Paykos.6

In order to surmise why some thought Quinn was Indian, we need to understand that he was a silent man, not given to idle conversation. Kieran tells a story about two Yankee ballplayers being out at a late hour one night, liberally imbibing of the cup that cheers. They observed a third figure, silent and unmoving in the darkness. They debated whether it was Jack Quinn or a cigar store wooden Indian. One of them investigated and reported back, “He didn’t say a single word.” His companion remarked, “Then it must be Quinn.”7 Because of this incident, some of his teammates began referring to Quinn as a wooden Indian. Perhaps some eavesdropping scribe thought they meant Quinn was of Native American ancestry and the story spread.

Pennsylvania writer Jim Zbick said the family was either Polish, Welsh, or Greek.8 Zbick did not say why he included Greek in the mix; perhaps he thought the name Paykos sounded Greek.

According to one Internet site, Jack’s parents were Anna Czarick and Michael Picus, who lived in St. Clair, a village about five miles north of Pottsville in Schuykill County, and attended the Immaculate Conception Church on Diener’s Hill in St. Clair.9 That particular Roman Catholic Church catered to persons of Slovak descent. Czarick sounds like a Slovak name. So could Quinn be of Slovak descent? Perhaps, but Anna Czarick was probably his stepmother. William C. Kashatus, a foremost authority on ballplayers from the anthracite coalfields, wrote that John Picus was born in Jeanesville, the son of Polish immigrants who ran a boarding house for coal miners.10 Kashatus is also the source of the information that the boy had a stepmother while still a child.11

Quinn signed his legal documents John Picus, but said his real name was something different, though he did not remember exactly what it was. He said his mother died when he was a few weeks old, his father married again to give him a stepmother, then his father died, and his stepmother married again to give him a stepfather, and the stepfather’s name was Picus, pronounced Py-kus, but Quinn said he thought it was of French origin and should be spelled Piqeues12 Whether the old spitballer expected anyone to believe his story is not known. Most authorities seem to think he was Polish.

Much of the above speculation about Jack Quinn’s birth and ancestry is probably misguided. Michael D. Scott has conducted extensive research and provided documentation that Quinn was born on July 1, 1883, in Stefurov, in the northwestern part of what is now the Republic of Slovakia, but was then a part of Austria-Hungary. According to Scott, whose research was published in NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture (Spring 2008, Vol. 16., No. 2), Jack’s original name was Johannes Pajkos and he was a son of Michael Pajkos and his first wife Maria, nee Dzjiacsko. The family arrived in New York on June 18, 1884, aboard the SS Suevia. Shortly after arrival in America, Maria died. Michael found work in the coal mines near Hazleton, Pennsylvania, and found women of Slovak descent to care for his infant son. In November 1887 Michael married Anastasia Tsar, who became Jack Quinn’s stepmother.

On Jack’s application for a Social Security card in 1939, the pitcher listed his name as John Quin Picus; his date and place of birth as July 5, 1884, in Mahoney City; his father’s Name as Michael Picus; and “Do not know” for his mother’s name. Scott suggests that Quinn did not know the facts about his birth.

All of this discussion about Quinn’s ethnic origins might seem to be much ado about nothing. But ethnicity was important to John Picus and other sons of immigrant coal miners who settled in the anthracite region in pursuit of the American Dream. Poor working conditions, low wages, and ethnic conflict resulted in tremendous hardships. As Kashatus points out, the miners sought refuge in the churches of their own ethnicity. They established fraternal societies and resided in their own ethnic groups in the small towns that dotted the anthracite region. Baseball was an important part of the assimilation process. Baseball flourished as a church-sponsored form of recreation and entertainment for coal miners and their families.13

For the young ballplayers, being raised in poverty and miserable working conditions, baseball offered a way out of the mines, a vehicle for upward mobility. In an era when professional baseball was dominated by Irish, English, and German names, it was not uncommon for sons of Polish immigrants to think their baseball careers might be helped by assuming a different surname. Bolinsky became Boley, Kowalewski became Coveleskie, and Wyshner became Gray. Szymanski became Simmons and Jablonowski became Appleton. Picus became Quinn, not only to avoid ethnic discrimination, but perhaps also to escape the derisive cognomen of “Pick Ass.”14

When he was about 12, John Picus became a breaker boy at the mines near Pottsville, working in tall, wooden structures where coal was broken and sorted for market. (Pennsylvania law stipulated that boys had to be at least 12 years of age to work in the coal breakers and 14 to work down in the mines. As the state had no compulsory birth registration, the laws could be circumvented by lying about the child’s age.) As each coal car emerged from the mine, it was pulled to the top of the breaker by a long, steel cable, where the car was tipped and the coal rushed down long chutes. The breaker boys separated the coal from the rock, slate, and other refuse as it streamed down, spewing black clouds of coal dust and smoke. To keep from inhaling the dust, the boys wore handkerchiefs and chewed tobacco in order to keep their mouths moist and prevent the dust from going down their throats.15

After a year in the breaker, John joined his father in the mine as a laborer, working an early shift so he could play baseball in the afternoon. Early in life he developed a combative personality, often challenging his stepmother who would not allow him to keep much of the money he earned for fear he would spend it on chewing tobacco.16 His mining career ended when a fire broke out in the pits, forcing him to escape by fighting his way for more than a mile through suffocating smoke.

For a while young Picus worked as a blacksmith, which helped develop his muscles, but he regarded it as an unhealthy occupation because it required him to breathe sulphur and charcoal fumes.17

So the teenager and an older companion hopped a freight and headed west, riding the rails as far as Montana sometime in the 1890s. In many cases he had to fight to survive. Quinn later recounted that his only possessions at the time were dirty, ragged clothes, a tattered cap, and his two fists.18 Around the year 1900 he returned to Pennsylvania. On the morning of the Fourth of July (probably in the year 1900) he arrived in the town of Dunbar, where the big event of the day was a baseball game between semipro teams of Dunbar and Connellsville. While he was watching the pre-game practice, a ball rolled toward him and he was instructed to throw it back, which he did with such velocity that the Dunbar manager offered him a job on the spot as a pitcher, promising him five dollars for a victory and two and one-half dollars if he lost. He won the game, pocketed the five dollars, and started a semipro career that lasted seven years, pitching for teams from Pennsylvania towns such as Dunbar, Connellsville, Mt. Pleasant, Berlin, and Washington. He later claimed that he was getting thirty dollars a month for pitching ball when he was fourteen years old, but he was probably at least sixteen or seventeen at the time.

When Quinn started employing the spitball is, like many other aspects of his life, a mystery. In a rare interview in 1930, he explained why he used it: “I didn’t take up the spitter because I especially like it although I learned to like it later. My fingers were so short I couldn’t get a grip on the ball well enough to throw an effective curve. With a fast ball and a spitter, however, I have developed a control that I think will rank as good as anybody’s in this circuit. If you bother to look up the records, you’ll find that I give up fewer bases on balls, year after year, in proportion to the amount of work I do, than almost any hurler in the league.”19 The records show Jack was right. In the decade starting in 1920 he twice led the league in fewest bases on balls per game and ranked in the top five 8 times in 10 years. No pitcher led more than twice, and no other ranked in the top five more than five times.

According to Zbick, Quinn did not consider his spitters to be as messy or repulsive as were those of the tobacco juice variety. Jack worked up his saliva with chewing gum, and he applied the juice by slightly touching two fingers to his lips. The “dry spitter” that Quinn delivered broke down sharply, but normally stayed in the strike zone. He kept batters guessing by faking the spitter on every pitch he threw, of course. He also used a no-name pitch that was a cousin to the knuckler. He threw it without using the index finger. He also developed an excellent change-up pitch.20

In 1903 Quinn pitched for Connellsville in the Pennsylvania State League before returning to semipro ball for a few years. In 1907 he posted a 6-5 record with Macon of the South Atlantic League in part of a season. In that same year he also pitched a few games for Pottsville in the outlaw Atlantic League, using the pseudonym Johnson. In 1908 he had an undefeated season, going 3-0 or 1-0 (sources differ) with the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association and then winning all of his 14 decisions for Richmond, including a no-hitter in defeating Norfolk 8 to 0 on August 28.

While Quinn was pitching for Richmond in a game against Lynchburg, he was “discovered” by Al Orth and soon thereafter drafted by the New York American League club, then known as the Highlanders.

Quinn made his major league debut on April 15, 1909, for New York against the Washington Senators. In the first inning he gave up two hits and one run, then settled down and pitched three-hit, scoreless ball the rest of the way. He pitched a complete game, allowing a total of five hits and no bases on balls in a 4-1 victory. Among those in attendance at this game were James S. Sherman, Vice President of the United States, and Ban Johnson, president of the American League. The win was the first of many over Washington by Quinn.

In 1910 Quinn had a strong season, winning 18 games against 12 losses for the Highlanders. He seemed well on his way to becoming a star. However, he slipped in 1911, winning only eight games while losing ten.

Things went from bad to worse for Quinn in 1912. In the seventh inning of a game against Detroit at Hilltop Park on May 11, Hippo Vaughn walked four straight batters, as the crowd yelled its displeasure at the balls called by umpire Silk O’Loughlin. In relief of the beleaguered Hippo, Quinn entered the game with the bases loaded and two out. Facing his first batter, he unleashed a wild pitch, allowing a runner to score from third. Then he buckled down and got out of the inning without further damage by striking out Oscar Stanage. In the next frame Quinn fanned Jean Dubuc for his second consecutive strikeout. Next up was Donie Bush. While pitching to Bush, Quinn became so angered at one of O’Loughlin’s calls that he threw his glove at the umpire. Silk ejected Quinn from the game. When protests by catcher Gabby Street and manager Harry Wolverton became too vigorous, they too were banished from the field. At this point some rowdy fans began hurling pop bottles from the stands toward the umpire. Two bottles came close to Silk’s head and one hit him on the foot. The New York Times reported that it was the first time in the history of Hilltop Park that a demonstration of that kind had taken place there.21 Order was eventually restored to the point where the game could be finished. Detroit won 9-5, and four Pinkerton men helped O’Loughlin to the dressing room, as the crowd again hissed and hooted and threw objects at him.

American League President Ban Johnson suspended Quinn indefinitely for throwing his glove at the umpire. The suspension did not last long. Johnson lifted it on May 17. On the next day Quinn started against Cleveland. The suspension had cost him one start at the most. However, he did not pitch effectively thereafter. In late July New York sold his contract to Rochester of the International League. After a short visit to Pottsville, he went through New York City on his way to report to his new club. Having been warned of recent activity by pickpockets in Gotham, the pitcher said he kept a weather eye open, but when he went to pay for his lunch, he discovered that his money—amounting to $125—was all gone. Nevertheless, he made his way to Rochester in early August and won eight games for the Hustlers before the season ended.

In 1913 Quinn won 19 games for Rochester and was acquired by the Boston Braves near the end of August. He won his first start for the Beantowners on the last day of the month, defeating Brooklyn 6-1. Although Quinn won only four games for the Braves in his short stay with them in 1913, he became the subject of a court battle the following year after he accepted $3500 to pitch for the Baltimore Terrapins of the upstart Federal League. A suit was brought in the United States District Court in Baltimore by James E. Gaffney, president of the Braves, asking for $25,000 in damages for the loss of Quinn’s services. Claiming that Quinn had already agreed to pitch for the Braves in 1914, the Boston club unsuccessfully sued Quinn, Terrapin officials, the Federal League, and its president for conspiracy. Undeterred by the suit, Quinn pitched Baltimore to a 3-2 win over Buffalo in the opening game of the Federal League season before 30,000 ecstatic fans. The Chicago Tribune reported it was the largest crowd ever to see a game in Baltimore and the most enthusiastic.22 The ex-coalminer went on to post 26 victories that season. The next year, however, saw a reversal of his fortunes. Jack led the league with 22 losses. After the Federal League folded, Quinn was unable to hook up immediately with a major league club and went back to the minors, signing with Vernon of the Pacific Coast League.

The spitballer had three highly successful seasons with Vernon, winning 53 games and posting an ERA of less than 3.00 each year. In 1917 he won 24 games for a last place club. In 1918 he led the Pacific Coast League with a remarkable 1.48 ERA, the best mark ever posted in that circuit during all its years as a Double A league. He also led the league in complete games with 22 and in strikeouts with 99 in the shortened season of 1918. He won at least 102 games in minor leagues affiliated with the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues. How many more he won in independent and semi-pro leagues is unknown.

After the Pacific Coast League suspended operations on July 14, 1918, because of the war, the National Commission announced that players in leagues which had suspended could join, during the emergency, any club willing to pay them a salary. However, the original holding club was to retain rights to their services. Charles Comiskey signed Quinn to a White Sox contract. Quinn joined the Sox on August 1 and had a 5-1 record for the Sox over the remainder of the 1918 season. Meanwhile, the Vernon club had sold the rights to Quinn’s services to the New York Yankees on July 19. After the season was over the New York Yankees lodged a claim for Quinn, and the National Commission had to decide whether the White Sox or the Yankees were entitled to his services. Meeting in December the Commission decided in favor of the Yankees, further strengthening the enmity between Comiskey and Ban Johnson, president of the American League and a member of the commission. Quinn declared he would prefer to remain with the Sox, but saw no chance of reversing the commission’s decision, so he signed with the Yankees.23

Quinn won 15 games for the New Yorkers in 1919 and improved to an 18-10 record in 1920. In the latter season he gave up the fewest bases on ball per game of any American League pitcher and ranked fourth in opponent’s batting average. In 1921 he slipped to an 8-7 record. That October he got his first World Series experience, being battered by the Giants, as he relieved Bob Shawkey in the third inning of a 13-5 loss. On December 20 Quinn, already considered old for a major league pitcher, was traded along with young pitchers Rip Collins and Bill Piercy and veteran shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh to the Boston Red Sox for shortstop Everett Scott and two top-flight pitchers, Bullet Joe Bush and Sad Sam Jones.

Quinn pitched well in Boston but could never win more than 13 games per season for the woeful Red Sox teams that owner Harry Frazee had stripped of stars. The spitballer continued to exhibit excellent control, ranking among the top five in the American League in fewest walks per nine innings during his entire stay in the Hub of the Universe. Used both as a starter and in relief, he was second in saves in 1923 and third in 1924.

On July 10, 1925, Quinn was sold to the Philadelphia Athletics for the waiver price. His record for the two clubs was 13-11. He again had the league’s second fewest bases on balls per game. In 1926 he won only ten games, but retained his excellent control, ranking third in walks per game. In 1927 his fortunes improved, as did those of his team. He had a 15-10 record for the second place A’s. Quinn’s remarkable control and his low-breaking spitball were major assets to the White Elephants’ young pitching staff as the A’s were on their way to becoming the top American League team from 1929 to 1931. Babe Ruth’s ghostwriter wrote that as a bluffer, Jack was in a class by himself. He bluffed the spitter on every pitch, but only threw it about one time in six pitches. He would go through the motions and then cross up the hitter with something entirely different.24

In 1928, at the age of 45, Quinn logged perhaps his best major league season ever. He won 18 games, while losing only seven, for a winning percentage of .750, fifth best in the league. He also ranked fifth in earned run average, and as was his habit, he had the second fewest bases on balls per nine innings. The secret to his success at an advanced age was his year-round conditioning program. During the off-season he did a lot of trap shooting at his lodge in Sunbury, Pennsylvania—an activity that he believed kept his eyes sharp. He also walked a great deal because he believed that a pitcher puts as much strain on his legs as on his arm. For an hour every afternoon he stood in front of a mirror and pantomimed his pitching motion. As he put it, this exercise kept his shoulder and arm muscles oiled up and prevented the stiffness that would otherwise set in after the season.25

In 1929 his win-loss record slipped to 11-9, but he still ranked in the top five in fewest walks per game. On October 12 the 46-year-old Methuselah became the oldest man to start a World Series game. Quinn got off to a good start in the game, pitching two-hit, shutout ball through the first three innings. In the fourth stanza he fell behind 2-0 when Kiki Cuyler’s single was followed by a home run by Gabby Hartnett. In the sixth, the roof fell in on the ex-miner. The Cubs knocked him out of the box with five successive singles. When the relievers could not check the carnage, five runs were charged to Quinn. The Cubs scored another run in the top of the seventh, and took an 8-0 lead into the home half of the inning. Then the White Elephants exploded with an avalanche of runs never before matched in any inning in the history of the World Series. The home team scored ten runs in the lucky seventh en route to a 10-8 victory in the greatest comeback ever achieved in the Fall Classic.

Although Quinn had been used occasionally in relief throughout his major league career, he had been primarily a starter until 1930, when he became mainly a reliever. He tied for second in saves among American League hurlers in 1930. On October 4, 1930, he became the oldest pitcher to finish a World Series game as he pitched the final two innings of the A’s loss to the St. Louis Cardinals. Earlier that season on June 27 he had become the oldest man ever to hit a home run in a major league game.26 On November 10 Connie Mack released the veteran spitballer to make room for a young right-handed pitcher he was calling up from Portland. The youngster, Hank McDonald, stayed in the majors two years and had a lifetime record of three wins and nine losses.

Quinn’s career was not over, however. Portland tried to get permission from the Pacific Coast League to employ the spitballer, but Quinn was more interested in another shot at the majors. An Associated Press reporter tracked him down in a cabin in the Pennsylvania hills, where Jack was following his favorite sport of hunting small game. He told the reporter: “I still think I’m good for another year. I’m going to look around the majors and get another year which will give me a record of real service that any player can be proud of. I’ve been kicking around the country since I was twelve years old when I started out with a battered suit and two hands and a stout heart, and I guess I can keep going. I’ve been in baseball so long I hate to give up the game. I don’t know what I will do if I don’t answer the spring training call.”27

He got his wish and then some. In January or February 1931 he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers as a relief specialist and led the National League in saves in both 1931 and 1932. (Save figures presented are based on retroactive calculation.) His 15 saves in 1931 set a new senior circuit single season record, which was tied twice in 1945, but not broken until 1947 when Hugh Casey of the Brooklyn Dodgers saved 18 games. After two good years in Brooklyn, Quinn was released by the Dodgers on April 29, 1933. It did not take him long to find additional employment. The Cincinnati Reds signed him on May 6. He appeared in 14 games for the Reds, recording one save and one loss. The Reds released him on July 13. At that point, Quinn’s 57 saves trailed only Fred Marberry’s record.

After Quinn was released by the Reds, he tried to resume his minor league career. On September 19, 1933, he pitched batting practice for the Los Angeles Angels, but was not offered a contract. The Angels did not want him, but they did not want him pitching for any of their rivals, either. On January 7, 1934, on a motion by Bill Lane, president of the Hollywood club, the directors of the Pacific Coast League voted 4-2 to allow Quinn to pitch in the PCL, using the spitball. The two negative votes were cast by the Angels and the San Francisco Seals. David P. Fleming, president of the Angels, said: “If the Hollywood club signs Quinn, we will protest any game in which he pitches and carry our protest to the National Association of the Minor Leagues and we believe we have a legitimate protest that the ruling body will uphold. The spitball is a nasty delivery and was voted out of organized ball; only pitchers who were registered spitball hurlers at the time it was barred were to be allowed to continue its use as long as they remained in the same league. Quinn was not in the Coast League when the bar was put on….I am sure that Judge W. H. Branham, president of the National Association, will uphold any protest we may be forced to make.28

Fleming overlooked the fact that Quinn had already changed leagues once since the ban was imposed. Originally on the American League list, he switched to the National League in 1931. Another spitball pitcher, Allen Sothoron, had done the same thing in 1924.

One week after the Pacific Coast League voted to make him eligible, but before he had yet been offered a contract, Quinn had a narrow escape that could have ended his career. He and three other passengers were injured when an automobile driven by his brother-in-law Ross Lambert was struck by a milk truck near Ada, Ohio. Jack was cut about the head and face, but was released from the hospital after receiving first aid. However, his wife and her two sisters were hospitalized overnight for the treatment of cuts and bruises. Luckily, the slight injury did not prevent the ancient pitcher from resuming his profession.

Despite the objections by the Angels, the Stars offered Quinn a contract. According to the Los Angeles Times, the 52-year-old spitballer signed and returned the contract by mail on February 23 from Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he was getting in shape to join the Stars at their spring training camp in Riverside. He made his first appearance of the season in relief in the second inning of a game against the Oakland Oaks. With three runs already in, two out, and two runners on base, the ancient hurler ended the inning by retiring the first batter he faced. In the third inning Quinn gave up two runs on three hits and was replaced. After three ineffective relief appearances, Quinn got his first win of 1934 on April 23, when he took the mound in the seventh inning of a tied game and pitched three scoreless innings while his teammates scored two runs in the ninth to defeat Seattle 8-6. That was his only win for the Stars. After only six games, one win and one loss, he was released.

In 1935 Quinn became manager of Johnstown of the Mid-Atlantic League and pitched two innings in one game, giving up two hits and no runs in his last appearance at the age of 52 or thereabouts.

Why was Quinn able to pitch far beyond the age when most hurlers are forced into retirement? One scribe wrote: “A powerful physique, an iron endurance, an easy delivery, and a placid mind are the four cardinal causes of his prolonged activities in the big show.”29

Quinn himself attributed his surprising longevity to peace of mind. “Nothing bothers me,” he told a reporter, “Why should it? The undertaker will get us all soon enough. There’s no need to meet him more than halfway. A lot of pitchers worry themselves out of the game. They cut their span of successful work by whole seasons. What a foolish thing to do! Pitching, with me, is a serious profession. I realize its importance and I like to pitch. Above all, I want to feel I can do good work. Naturally I want to win. So far so good. All that’s mere horse sense. But much as I like to win, I’m not crazy about it. I realize the other fellow wants to win, too. If I’m lucky enough to get the breaks, well and good. If he outlucks me, I may get my turn next time. Doing his best is no more than a pitcher is paid for. Bearing down in the pinches is what he is supposed to do. But that isn’t worry and it isn’t physical strain. I get tired after a hard ball game just as other pitchers do, but I don’t get sick and hang around half the night unable to eat my supper. And I don’t lie awake till morning wondering what might have happened if I’d pitched a little inside instead of outside to a certain batter. Overdoing a thing is half doing it. There’s only one right way to pitch a ball game. Do your best and let it go at that. Fussing and stewing and fretting is like throwing grit into the machinery.”30

Few people regard Jack Quinn as a great ballplayer, but he was a very good one for many, many years. Perhaps he never had a great season, but he had more good years than most. He has not been named to the Baseball Hall of Fame but he won as many games as most of the 20th-century pitchers enshrined in Cooperstown. Among Hall of Fame notables with fewer victories than the old spitballer are Joe McGinnity, Ed Walsh, Three Finger Brown, Stan Coveleskie, Herb Pennock, Dizzy Dean, Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Juan Marichal, and Whitey Ford. John Lardner was disappointed that Quinn was not elected to the Hall. He wrote: “I voted for the ageless John Picus Quinn, who pitched his spitball even longer than Faber, if not quite as well.”31

Quinn married Georgenia Viola Lambert. She died in July 1940 in Dolton, Illinois. They had no children. After his wife’s death he moved back to his native Pennsylvania, where he spent his time in a Pottsville bar pitching pennies, talking sports, and drinking to excess.32 In January 1946, he entered Good Samaritan Hospital in Pottsville, where he died on April 17, after an illness due to a liver infection, perhaps brought on by alcohol abuse. Never one to seek publicity, he had lived in comparative obscurity for nearly a decade. He was buried in Charles Baber Cemetery in Pottsville in the anthracite coal country from which he had sprung.

This account is adapted from the chapter on Jack Quinn in Charles F. Faber and Richard B. Faber, “Spitballers: The Last Legal Hurlers of the Wet One” (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Publishers, 2006).

Photo Credit

Library of Congress

Notes

1 Los Angeles Times, April 19, 1946.

2 Lane, F. C. “The Oldest Veteran in the Major Leagues.” Baseball Magazine, September 1930: 443.

3 “Necrology.” Sporting News, April 25, 1946.

4 Kieran, John “Name, Please.” New York Times, May 21, 1936.

5 Kieran, John. “The Russian Rookie with the Robins.” New York Times, February 12, 1931.

6 Allen, Lee. “Baseball Methuselah — Jack Quinn Big Leaguer at 49.” Sporting News, Sepember. 9, 1963.

7 Kieran, “The Russian Rookie with the Robins”

8 Zbick, Jim. “Jack Quinn: Ageless Wonder,” www.tnonline.com. (May 17, 2003).

9 www.fortunecity.com/vicorian/mill/1215/wmorris.htm (6-11-2004).

10 Kashatus, William C. Diamonds in the Coalfields: 21 Remarkable Baseball Players, Managers, and Umpires from Northeast Pennsylvania. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002: 11.

11 Ibid.

12 Kieran, John. “The Jack Quinn Mystery, Third Episode.” New York Times, July 29, 1931.

13 Ibid., pp. 1-2.

14 Ibid., p. 35.

15 Ibid., pp. 8-9.

16 Ibid., p. 11.

17 Lane, op. cit.

18 Zbick, op. cit.

19 Lane, op. cit.

20 Zbick, op. cit..

21 “Shower of Bottles Greets O’Loughlin,” New York Times, May 12, 1912.

22 “Baseball War and Its Strategy Now Fade into the Background.” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1914.

23 New York Times, December 13, 1918.

24 Ruth, George Herman. Babe Ruth’s Own Book of Baseball, Bison Book Edition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992: 55-56.

25 Kashatus, op. cit: 105.

26 This record stood for over 75 years until it was broken by Julio Franco on April 20, 2006.

27 Washington Post, November 13, 1930.

28 Ray, Bob. “Quinn’s Spitball Gets Okeh,” Los Angeles Times, January 9, 1934. The same newspaper reported in its January 24th edition that the vote was 5-1, with the Seals listed on the affirmative side in this account.

29 Lane, op. cit.

30 Ibid.

31 Lardner, op. cit.

32 Kashatus, op. cit.: 122.

Full Name

John Picus Quinn

Born

July 1, 1883 at Stefurov, (Slovakia)

Died

April 17, 1946 at Pottsville, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.