Charles Bronfman

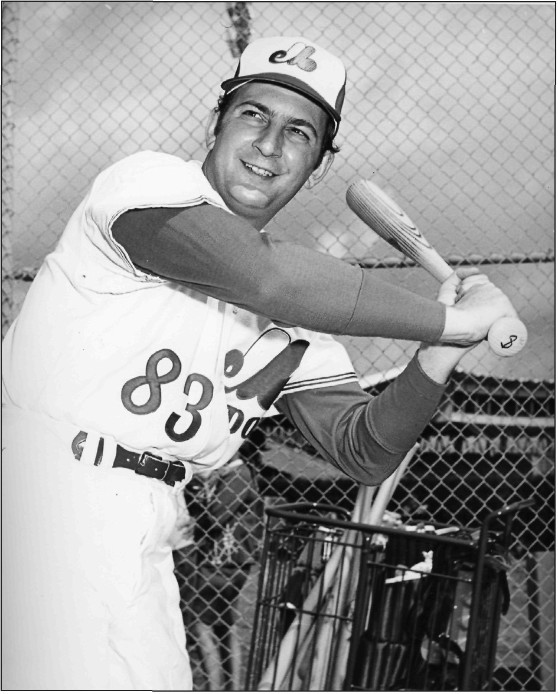

Montréal Expos’ owner Charles R. Bronfman, wearing his familiar uniform number 83 at spring training, West Palm Beach, Florida, March 1969. (McCord Museum, Montréal)

For 22 years, the name Charles Bronfman was synonymous with major-league baseball in Montréal. As the son of immigrants who made their fortune in the whiskey trade, Charles made a name for himself in his own right. At the age of 37, he raised the funds required to obtain an expansion baseball franchise in the National League. The Expos under Charles’s stewardship put an entertaining product on the field in spite of the external forces of baseball economics and national unity politics. His baseball days behind him, he applied his values as a Canadian and as a Jew to improve the lives of others.

The saga of the Bronfmans originated in the town of Otaci, in the region of Bessarabia, in the Russian Empire. In 1880 Yechiel Bronfman married the former Mindel Elman.1 The Bronfmans were tobacconists, and although they grew quite wealthy, their affluence was no match for the prevailing anti-Semitism throughout the Russian Empire. A wave of pogroms ensued after the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881. The Bronfmans felt no choice but to flee, departing with their four children, servants, and personal rabbi for the New World in 1889.2 The youngest of the four, an infant named Samuel, grew to become the patriarch of the Bronfmans.

Yechiel settled his family first in Wapella, Saskatchewan, and then in Brandon, Manitoba. Mindel delivered four more children, and by 1903 the family had recovered enough of its wealth to purchase the Anglo-American Hotel.3 Prescient in his business acumen, young Samuel observed that the profits of the hotel were concentrated in the sale of alcoholic beverages. ‘Mr. Sam,’ as he would become known, soon entered the liquor trade. Meanwhile, in the United States, Congress on October 28, 1919, passed the Volstead Act, which prohibited the sale of alcoholic beverages. Mr. Sam saw an opportunity. He would sell whiskey to American entrepreneurs, but his doing so in Canada made his business perfectly legal. Mr. Sam founded the Distillers Corporation in Montréal in 1924.4 By 1928, he had accumulated enough capital to purchase Joseph Seagram & Sons.5 Mr. Sam had married the former Saidye Rosner in 1922; they had four children: Minda, Phyllis, Edgar, and the youngest, Charles Rosner Bronfman, on June 27, 1931.

The Bronfman family lived at 15 Belvedere Road in the Montréal suburb of Westmount.6 For his education, Charles attended Selwyn House in Montréal and Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario. Meanwhile, Mr. Sam’s empire continued to expand. According to Charles’s memoirs, by 1933, “the Company had 40 percent of the Canadian whisky market.”7 Mr. Sam was the president of the Canadian Jewish Congress from 1939 to 1962, and became an important benefactor to both McGill University and the Israel Museum. These lessons of philanthropy and community activism were not lost on young Charles and his siblings.

After attending McGill University, Charles went to work for Mr. Sam on March 12, 1951.8 He was appointed to run the Adams whisky label in 1954, and in 1958, “at the grand old age of 27,” he was made president of the House of Seagram.9 In 1961 he married the former Barbara Baerwald; they had two children, Stephen and Ellen.

During the 1950s and ’60s, the Seagram’s empire expanded its horizons beyond whiskey, entering both the real estate and oil markets. Meanwhile, Mayor Jean Drapeau was concocting his latest grand projet for the city of Montréal. During his 30-year tenure as mayor, Drapeau put Montréal on the world stage with Expo 67, Place des Arts, the Metro system, and the 1976 Summer Olympics. Now he was trying to convince Major League Baseball that Canada’s largest city should be awarded an expansion team.

Montréal had a storied baseball history as the top farm club for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Charles Bronfman was 15 years old when Jackie Robinson led the Montréal Royals to the Little World Series in 1946. As he told biographer Howard Green, “my mother [maintained] I was crazy about baseball as a kid. … [I]f she was implying that I played it, that’s not the case. I just followed it.”10 The expansion fee for a National League team was $10 million, and Charles offered to put up 10 percent with his own money. His wife, Barbara, questioned his decision to invest: “A million dollars and you just say yes?” “Well,” he replied, “it’s never going to happen anyway.”11

“But happen, it did,” in the words of Donald Sutherland.12 Montréal, along with San Diego, was awarded a National League expansion franchise on May 27, 1968. Much like Pierre Trudeau, a fellow Montréaler who was elected Prime Minister in 1968, Charles cited “reason over passion” for his investment in the baseball team. At a time of a burgeoning sovereigntist movement in Quebec in the wake of the Quiet Revolution,13 Charles envisioned a baseball team as a unifying force, not only in Quebec, but throughout Canada.

The other major investor, Jean-Louis Lévesque, did not share Charles’s enthusiasm, and withdrew from the project. Finding a place to play was another ordeal, as the Autostade, home of the football Alouettes, was rejected for baseball. Would the franchise be snapped up by a city like Milwaukee, Buffalo, or Dallas before even taking the field?

“I’d go to see Drapeau, and he would tell me everything was wonderful. And by the way, when I went to see Drapeau, I used to do this. I used to pinch myself and say ‘He’s a salesman, he’s a salesman, he’s a salesman. Don’t believe him; he’s a salesman.’ Then I used to see [Lucien] Saulnier, Drapeau’s assistant. And Saulnier had two words that were fabulous. They were ‘Definitely not.’”14

Montréal journalists Russ Taylor and Marcel Desjardins had shown National League President Warren Giles the layout of Jarry Park, a 3,000-seat facility in the north end of the city where home plate faced west, rather than east. Giles was confident that the stadium could be upgraded to meet National League standards by April 14, 1969. Charles eventually put together a consortium supported by Lorne Webster and Hugh Hallward to finance the requisite $10 million investment.15 Montréal was getting a team, named the Expos after the World’s Fair of 1967.

Appointed to oversee the operation were President John McHale, general manager Jim Fanning, and manager Gene Mauch. Fanning remembered the strategy the Expos undertook to build the inaugural roster: “We went for the players who had a name, who could still play, and who had trading value, or they had value, period.”16 The Houston Astros saw sufficient value in the Expos’ expansion draft to offer Rusty Staub in a trade for Donn Clendenon and Jesus Alou. Controversy ensued when Clendenon refused to report to manager Harry Walker in Houston. On the eve of the regular season, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn ruled that the trade stood, with the Expos offering Houston Jack Billingham and Skip Guinn as alternate compensation.

Charles remembered the afternoon of April 8, 1969, as Maureen Forrester sang ‘O Canada’ before the Expos’ first game versus the Mets at Shea Stadium: “I remember standing there with tears rolling down my cheeks as 40,000 Americans were standing at attention for our National Anthem. In hockey, yes, Canada was well known but in baseball[?] … suddenly, we were in the big leagues. Canada was in the big leagues, and I had helped make it happen.”17

The Expos defeated the Mets 11-10 on a trio of home runs, including one by Rusty Staub. ‘Le Grand Orange,’ as Staub was known, became as legendary in baseball during his three years with the Expos as Jean Béliveau was in hockey. Montréal also won the home opener, an 8-7 victory over the St. Louis Cardinals, with Mack Jones hitting the first major-league home run on Canadian soil.

“The best part of that game,” remembered Charles, “was having my mother and father with me. My dad had given me quite a ‘what-for’ about this whole procedure and then, when he knew that I had put up the money myself, became the biggest and best Expos’ fan in Canada,” adding that “he couldn’t understand why I wasn’t up until 2 in the morning listening to baseball games the way he was.”18 Two years after the opener at Jarry Park, in 1971, Mr. Sam died at the age of 82.

The 1969 Montréal Expos finished in last place, as expected, with a record of 52-110. However, they set an expansion record by attracting over 1.2 million fans to Jarry Park. According to Peter C. Newman, the Expos drew red ink in 1969 before turning a profit annually from 1970 through 1975.19 However, on the field, not once did they breach 79 wins or finish in the first division. It was a frustrating time for Charles as owner of the Expos.

To compound matters, Canada became embroiled in a global energy crisis; in Quebec, the impact was felt even more keenly, as the movement for national sovereignty was gaining momentum. In baseball, it was only a matter of time before the reserve clause would give way to unrestricted free agency for the players. It was amid this economic climate that on December 4, 1974, the Expos felt compelled to trade two of their star players, Ken Singleton and Mike Torrez, to the Baltimore Orioles: “Every club makes lots of little mistakes, but that was a biggie. In the development stage of this club, that set us back two or three years. The fact that in effect, we got nothing for those two fine players. We got Rich Coggins, who was sick, and Dave McNally, who quit. I think we sold Coggins’ contract to the Yankees for $100,000, so that’s what we got out of Singleton and Torrez.”20

As the last-place Expos prepared to move from ramshackle Jarry Park to futuristic Olympic Stadium in 1976, baseball finally ushered in a new system of free agency. Charles and the Expos courted Baltimore outfielder Reggie Jackson to play for his former manager Dick Williams in Montréal. George Steinbrenner, meanwhile, could offer Reggie the city of New York and a contending team. In 1977 Jackson was wearing pinstripes and playing in the World Series. He would not be the last blue-chip free agent to spurn an offer to play for the Expos. They also lost Don Sutton to the Houston Astros in 1980.21

The Expos knew they had to draw attendance of 1.7 million at the 59,500-seat Olympic Stadium simply to break even, or more than that in order to turn a profit.22 After failing to reach that figure in both 1977 and 1978, and with the franchise having yet to post a winning season, Charles seriously considered divesting himself of the Expos.23 Fellow board member Lorne Webster persuaded him to stay. It was a decision Charles would not regret, as la belle époque of the franchise was about to begin.

In the words of Canadian Broadcasting Corporation anchor Knowlton Nash, “after a decade of trying” the 1979 Expos were “considered to be one of the strongest clubs in the game.”24 Led by a collection of young homegrown players, including Gary Carter, Larry Parrish, Steve Rogers, Ellis Valentine, Warren Cromartie, and Andre Dawson, the Expos were complemented by veterans from other organizations like Tony Perez, Bill Lee, and Woodie Fryman. Carter, Parrish, and Rogers represented the Expos at the All-Star Game in Seattle on July 17. At the midway point of the season, the Expos stood 2½ games ahead of the Chicago Cubs with a record of 50-35, the best in the entire National League. “You know, when you’re winning, all of a sudden the world is I think a lot better place to be,” said Charles in a 1979 interview. “Last year, we had a disappointing result [of 76-86] with a pretty good team. You try to have a winning team for the good of the city that has other added benefits.”25

When the 1979 season concluded, the Expos posted a superlative record of 95-65, drawing over 2.1 million fans to Olympic Stadium. Although the team lost the divisional title to the Pittsburgh Pirates, the Expos had cemented themselves for one brief shining moment as Canada’s team. As was reported late in the season in one telegram from Ottawa, “no matter what happens, you’ve given baseball fans across the country a thrilling summer. Bravo.”26 The telegram was signed by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, whose late father Charles-Emile once owned the Montréal Royals.

The Expos and their first pennant race occurred at a time when national unity was at the forefront of the Canadian consciousness. On November 15, 1976, René Lévesque of the Parti Québécois won a majority government on a platform that included a referendum on sovereignty-association. Prior to the election, Charles was quoted in the Montréal Star as vowing “to get out if the PQ wins.”27 Three years later, he was asked to offer his remarks on any link between the success of the Expos and national unity: “This year, there is just a tremendous outflow of goodwill, and everybody is very happy. How that might translate itself politically, I wouldn’t have the vaguest idea. I would hope that it would translate itself obviously in a positive way but that’s not why we’re trying to have a winning team.”

Quebec held its referendum in 1980, with 59 percent of the province voting on May 20 to remain in Canada. Meanwhile, with Ron LeFlore added to the lineup, the Expos raced to another stellar season. Despite 81 days in first place, they lost the pennant once again during the final weekend, this time to the Philadelphia Phillies. The disappointment did not stop the Expos from being awarded a lucrative television broadcast deal. Starting in 1981, O’Keefe Ale agreed to sponsor Expos telecasts covering Canada from coast to coast for $35 million over five years.28

The broadcast deal proved to be a Pyrrhic victory for the Expos. After a grievance was filed by the Toronto Blue Jays, the Commissioner’s Office ruled that the television contract infringed upon the Blue Jays’ territorial rights. Expos telecasts would be blacked out in southern Ontario.29 John McHale mused that “when Montréal became a Quebec-only team, and no longer had the right to compete in Canada, that was a very telling blow to our financial picture.”30 This was the very antithesis to the philosophy behind Charles’s involvement with the Expos in the first place.

Notwithstanding the television contract, expectations for the 1981 Expos as baseball’s ‘Team of the ’80s’ were high. The team welcomed young players Tim Raines, Tim Wallach, and Jeff Reardon in the early months of the season. However, only two weeks after acquiring Reardon from the Mets, the Expos – and all 25 other teams – were shut down by a players strike on June 12. While the economic losses were significant, $500,000 in the first weekend alone, the positioning of the work stoppage actually helped the Expos in the standings.31 “We were third in our division when the strike happened,” Charles told biographer Howard Green. “Then on August 6, after a settlement was reached, the owners agreed to split the season. Playoff berths were guaranteed for the four teams who were leading their divisions …whichever teams had the best record in the second ‘half… also got playoff berths.”32

As the team leading the division when the strike began, the Phillies had already clinched a playoff spot. The Expos were leading the Cardinals by 1½ games on the morning of October 3. With the magic number reduced to one, the Expos trailed the Mets 3-2 as rookie Wallace Johnson rapped a triple to drive home two runs. That proved to be the margin of victory as the Expos clinched the division. “In our bar mitzvah year,” Charles exclaimed, “the Expos finally came of age.33

After defeating the Phillies in a five-game Division Series, Montréal went on to face the Dodgers in the League Championship Series. The series was tied, two wins apiece, on October 19, when Ray Burris faced Fernando Valenzuela at Olympic Stadium. Through eight innings, both teams were limited to one run. Jim Fanning, now the Expos’ manager, summoned Steve Rogers to pitch the ninth inning. With two away, Rogers threw a ball to Rick Monday that landed in the center-field bleachers. Charles remembered his reaction. “I wasn’t upset. John McHale looked like he was going to croak. I said, ‘John, why are you so upset?’ He said, ‘Charles, this doesn’t happen very often. And when it does happen and you don’t take advantage, it won’t happen again for a while.”34 History would support McHale’s clairvoyance, as the franchise did not return to the postseason for as long as it remained in Montréal.

More trouble was on the horizon for the Expos in 1982. Gary Carter, the reigning All-Star Game MVP and face of the franchise, who batted .438 in the NLCS against the Dodgers, was one year away from free agency. Rather than risk losing Carter at the end of the season, the Expos signed him to a contract extension prior to spring training. According to the Washington Post, the contract paid Carter $15 million over eight years.35 It was a deal Charles regretted from the moment he signed it: “We never won with Gary Carter, and when he was asking for two million dollars a season … [John] McHale and I were furious. Still, we held our noses and did the deal because we felt we had no choice.”36 While the Expos continued to set franchise attendance records in 1982 and 1983, outdrawing the Yankees both years, the large crowds were less than enthused by the third-place performances on the field. A fifth-place finish followed in 1984. Not reaping the desired return on investment on the Carter contract, the Expos traded him to the Mets on December 10, 1984. “When a team comes that close and doesn’t do it,” Charles reasoned, “eventually you have to break up the team.”37

The ‘Team of the ’80s’ was consistent if unspectacular for the latter half of the decade. In 1986, as Gary Carter won his World Series ring with the Mets and les Canadiens won yet another Stanley Cup, the Expos drew barely one million fans. Olympic Stadium, its roof finally installed in 1987, had not aged well. While the facility was originally estimated to have cost $124 million, the Canada Broadcasting Corporation reported that the actual cost was $1.5 billion.38 At a time when revenues were generated in increasingly weak Canadian dollars, escalating salaries were paid in US dollars.

The breaking point took place in 1989. In a stunning role reversal, the Expos traded three pitching prospects, Brian Holman, Gene Harris, and 6-foot-10 Randy Johnson, to the Seattle Mariners for Mark Langston. Initially, the deal was a success, as the left-hander helped to propel the Expos to the top of their division. In the final eight weeks of the season, Langsten’s impending free-agent status became a distraction as the Expos plummeted from first place to fourth. Finally, in late September, Charles suggested to club investor Hugh Hallward that they meet for dinner at an Italian restaurant instead of going to the game. When they sat down, Charles turned to Hugh and asked, “You know what this means, don’t you?”39 The Expos were for sale.

“I was very bitter,” Charles told Danny Gallagher. “I had a Plan A, a Plan B, and a Plan C. Plan A was to sell the team to someone who would [stay] in Montréal; Plan B was to sell to someone who would … keep the team in Montréal for five years; Plan C was to sell to the highest bidder anywhere.”40 On June 14, 1991, the National League announced that the Expos had been sold to a consortium led by former Seagram’s executive Claude Brochu for a reported $100 million.41

Charles Bronfman was now 60. Now married to his second wife, Andrea, he had reached an age when most people look toward retirement. Charles’s mind, however, was headed in a different direction: philanthropy. In 1991 his CRB Foundation pioneered the ‘Heritage Minutes,’ a series of 60-second films that illustrated pivotal moments in Canadian history. In 1994 Charles and Michael Steinhardt founded Birthright Israel, an educational organization that sponsored free trips to Israel for young Jewish adults. By the time Seagram’s had been sold to Vivendi in 2000, Charles and Andrea had relocated to New York. Since 2004, Charles has awarded an annual Charles Bronfman Prize to young humanitarians whose work, grounded in Jewish values, is of universal benefit. Tragedy struck the Bronfman family on January 23, 2006, when Andrea was fatally struck by a passing vehicle in New York.

Charles married Rita Mayo in 2012, and in subsequent years they divided their time among New York, Montréal, and Florida. He is the proud grandfather of six.42 On June 27, 2021, Charles celebrated his 90th birthday by watching a virtual performance of the ‘Concert in Denim.’ It was performed by Israel Philharmonic at the Charles Bronfman Auditorium in Tel Aviv. A member of the Order of Canada, he was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984. In 1992 Charles was honored by the Blue Jays, who invited him to throw out the first pitch before Game Three of the World Series in Toronto. The Expos’ Opening Day hero, Mack Jones, was once described as “one man who has not forgotten his roots.”43 That same honor may also be bestowed upon the man who brought the Mayor of Jonesville to Montréal, Charles Rosner Bronfman.

Notes

1 Peter C. Newman, Bronfman Dynasty: The Rothschilds of the New World (Toronto: McLelland and Stewart Limited, 1978), 12.

2 Michael R. Marrus, Mr. Sam: The Life and Times of Samuel Bronfman (Toronto: Penguin Books Canada Limited, 1991), 24.

3 Newman, 70.

4 Marrus, 113.

5 Marrus, 130.

6 Charles Bronfman and Howard Green, Distilled: A Memoir of Family, Seagram, Baseball, and Philanthropy, (Toronto: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd., 2016), 4.

7 Bronfman, 4.

8 Bronfman, 52.

9 Bronfman, 59.

10 Bronfman, 19.

11 Bronfman, 76.

12 Brian Schecter, ed., Les Expos, Nos Amours, English edition (Montréal: TV Labatt, 1989).

13 Rene Durocher, “The Quiet Revolution (Révolution tranquille) was a time of rapid change experienced in Québec during the 1960s.” Canadian Encyclopedia article published online July 30, 2013.

14 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

15 Danny Gallagher and Bill Young, Remembering the Montréal Expos (Toronto: Scoop Press, 2005), 26.

16 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

17 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

18 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

19 Newman, 267.

20 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

21 Alain Usereau, The Expos in Their Prime (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013), 104.

22 Newman, 268.

23 Gallagher, 27.

24 Mark Phillips, “Win Some, Lose Some,” on News Magazine (Toronto: The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, June 1979).

25 “Win Some, Lose Some.”

26 Norm King, 7979; The Expos First Great Season (Toronto: Scoop Press, 2021), 189.

27 Jacques Doucet and Marc Robitaille, Il était une fois les Expos: Tome 1, les années 1969-1984 (Montréal: Editions Hurtubise Inc., 2009), 282.

28 Usereau, 109.

29 Brodie Snyder, The Year the Expos Finally Won Something (Toronto: Check Mark Books, 1981), 163.

30 Usereau, 109-110.

31 Snyder, 160.

32 Bronfman, 95.

33 Jeff Katz, Split Season: Fernandomania, the Bronx Zoo, and the Strike That Saved Baseball (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2015), 245.

34 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

35 Usereau, 153.

36 Bronfman, 97.

37 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

38 Bronfman, 92.

39 Bronfman, 101.

40 Gallagher, 28.

41 Jacques Doucet and Marc Robitaille, Il était une fois les Expos: Tome 2, les années 1985-2004, (Montréal: Editions Hurtubise Inc., 2011), 206.

42 Correspondence with Charles Bronfman, December 8, 2021.

43 Les Expos, Nos Amours.

Full Name

Charles Rosner Bronfman

Born

June 27, 1931 at Montreal, Ontario (Canada)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.