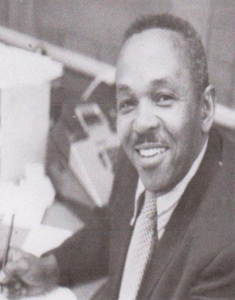

Charles England

Charlie England’s baseball story is intertwined with the vagaries of growing up as an African-American in North Carolina in the Jim Crow era and beyond. His brief tenure with the Newark Eagles was bookended by longer careers as a college and semipro baseball player and later as a college coach, mentor, and much-lauded community leader who broke the color barrier to achieve success on and off the field.

Charlie England’s baseball story is intertwined with the vagaries of growing up as an African-American in North Carolina in the Jim Crow era and beyond. His brief tenure with the Newark Eagles was bookended by longer careers as a college and semipro baseball player and later as a college coach, mentor, and much-lauded community leader who broke the color barrier to achieve success on and off the field.

Charles Macon England was born on September 6, 1921, in Newton, the county seat of Catawba County in the uplands of west-central North Carolina. His parents were Guy Leroy and Katie (Duncan) England. His grandparents were born into slavery not long before the end of the Civil War. England’s family has deep roots in Catawba County. Charlie had two brothers and two sisters who survived to adulthood. His older brother, Horace, enlisted in the US Army during World War II. He re-enlisted to serve in the Korean War, was captured by the enemy in North Korea, and died as a prisoner of war. His remains were never found. Charles’s younger brother, Warren, also served in the Army during World War II. After he was discharged from the Army, he returned to Newton. Charles’s two sisters were Marion England Burgin and Betty Jean England Gibbs. His parents and all of his siblings except Horace are buried in Catawba County.

Life for the England family in Newton during the Jim Crow era was full of challenges, setbacks, tragedies, and accomplishments. Guy England worked a variety of jobs. He was the janitor for the Catawba County Courthouse and a fireman at a textile mill, where he had the backbreaking job of stoking the mill’s boilers. Katie also did tedious labor – she was a laundress in the days before modern washing machines. Their hard work paid off and by 1930, they owned their home in Newton and made sure their children attended school.

During the 1930s the England household began to unravel. In 1933, when Charles was 12 years old, his mother died at age 39 from pneumonia, a complication of influenza. A year later his father was remarried to Vanda Hewitt Frye, also recently widowed. Less than a year later, Vanda’s son, Richard Frye Jr., was killed in a truck accident that also took the lives of nine other African-Americans who were on their way to a picnic. In the midst of family turmoil and grief, Charles England went to live with his maternal grandparents, Warren and Alice Duncan. Warren was a house painter and Alice Duncan toiled as a washerwoman.1 Charles was living with his grandparents when he graduated from Central High School in Newton.2

The first mention of a baseball game in the Newton Enterprise came on July 14, 1883, when the Newton Nine lost the first game of the season to the Statesville Nine.3 As early as the 1870s, “colored nines” competed in organized leagues at the local, regional, and state levels. Some cities, like Asheville, had more than one team. The success of black baseball teams in the decade after the Civil War prompted the Tarboro Enquirer Southerner to complain, “Is it not time that the whites retire from the game?”4

Coverage of colored baseball teams continued sporadically in Catawba County newspapers through the early 1900s. One such nine, the Newton Colored Base Ball [sic] Team, traveled throughout western and central North Carolina to play local and college teams, often playing their home contests on the now-defunct Catawba College diamond.5 By the 1930s, numerous colored nines were playing in local and regional leagues.

Local newspapers’ attention to sporting events at Charles’s Central High School were virtually absent. The school offered little in the way of extracurricular activities. In the late 1930s, when Charles attended the segregated school, it was described as having “broken windows, bare light bulbs suspended from the ceiling, and only one pot-bellied stove.”6 Athletic facilities were nearly nonexistent save an outdoor patch of dirt that passed for a basketball court – there was no gym.7 Any opportunities for Charles to play competitive baseball came from elsewhere. While records are scarce and evidence slim, it is likely that England had his first baseball experiences in the 1930s with one of the colored nines in Catawba County before he graduated from Central High School to head off to college.

England enrolled at the historically black Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, for the 1940-1941 academic year. He was a star pitcher for the Bears and played on the basketball team. Shaw engaged in intercollegiate baseball skirmishes as early as 1898 against their crosstown rival, St. Augustine’s School (now St. Augustine’s University). Shaw began fielding an intercollegiate-conference baseball team in the 1910s. All of their games were against black colleges and most were in North Carolina.

England was a student at Shaw University in 1942 when he registered for the World War II draft. At the time he was unmarried, and he named his grandmother Alice as the “person who will always know your address.”8 Besides attending the university, he took welding classes at a vocational-technical school in Rocky Mount. When he enlisted in the US Army at Fort Bragg on January 19, 1945, England had two years of college and a skillset that included welding and “flame cutting.” He was described as being 5 feet-7½ inches tall, and weighing 150 pounds. But it was not his welding skills that got him through his military service – it was his firepower on the mound.

England completed all of his Army service in the United States. Fourteen months after he joined the Army, he was a sergeant in the Quartermaster Corps. At Camp Lee, Virginia, he was a pitcher for the Travelers, the Camp Lee baseball team.

The Travelers played military and civilian teams throughout the mid-Atlantic region. (Its home field was Nowak Field, named in honor of Sgt. Henry “Hank” Nowak, a St. Louis Cardinals minor-league pitcher who was killed in action in Belgium on January 1, 1945, during the Battle of the Bulge.)

Major-league players who played for the Travelers included Jim Greengrass, Granny Hamner, Johnny Lindell, and Porter Vaughan, as well as two future Hall of Famers, Luke Appling, who was a player-manager for the Travelers in 1944; and Red Ruffing, who pitched at least one game for Camp Lee in the spring of 1945.

During World War II, US military bases organized traveling baseball and football teams that played against military and civilian squads. Four years before Jackie Robinson broke major-league baseball’s color barrier, the Army was already fielding mixed-race teams. The relatively progressive attitudes of the military stood in stark contrast to the segregated teams on college campuses and civilian life. But the Army saw integrated sports teams as a means to foster unity and patriotism, and promote some semblance of racial harmony in its forces.9 Camp Lee, named for the Confederacy’s Robert E. Lee and situated in the heart of Jim Crow country, was among the Army installations that allowed white and black players on the same teams. (The baseball team, the Travelers, was nicknamed for Lee’s favorite horse.) Cpl. Ernest R. Rather in the Chicago Defender observed, “On the buses, though segregation is the rule in Virginia, it is not observed in practice within the Camp Lee limits”10

According to a 1967 newspaper article, Charles England was the first African-American to play on the Travelers baseball team.11 That assertion is likely incorrect. Before England arrived at Camp Lee in 1946, other black ballplayers had integrated the squad. As early as 1943, George Crowe played first base on what had previously been an all-white nine. After World War II Crowe played for the New York Black Giants (1947-1949) and played nine major-league seasons (1952-1953; 1955-1961) for the Boston and Milwaukee Braves, Cincinnati Reds, and St. Louis Cardinals. Crowe also played professionally for several basketball teams including the Harlem Globetrotters and the Los Angeles Red Devils in the National Basketball League, where one of his teammates was Jackie Robinson. In 1944, two years before Charlie England reported to Camp Lee, former Negro League player William McKinley “Sug” Cornelius was pitching for the Travelers. Sug’s résumé included stints on the mound for the Nashville Elite Giants, Memphis Red Sox, Birmingham Black Barons, Chicago American Giants, and Cincinnati Buckeyes. So clearly England was not the first African-American to play for the Travelers. But that historical correction does not diminish his baseball accomplishments or his contributions to racial equality and the civil-rights movement.

The first mound appearances by Sgt. Charles M. England for the Camp Lee Travelers took place in the spring of 1946. In his first outing, on April 10, he pitched two innings in relief in a losing effort against the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Barons of the Class-A Eastern League, a farm team of the Cleveland Indians.12 The winning pitcher for the Barons was Joe Tipton, who after the war played seven seasons for American League teams between 1948 and 1954. The losing pitcher for the Travelers was Bob Chakales, who also spent seven seasons in the majors, pitching for several American League teams. About two weeks later, Charlie England pitched in relief against the Binghamton (New York) Triplets of the Eastern League, a New York Yankees farm team. This time, England and the Travelers came out on top, 4-3, before a crowd of 5,000 at Camp Lee.13 England gave up 11 hits but yielded just two runs to notch the win.

The last mound appearance by England in a Travelers uniform came on June 29, 1946. He pitched a three-hitter against Quantico as the Travelers defeated the Marines, 8-1. Less than three weeks later, England was honorably discharged. He spent his Army service – one year, eight months, and two days – as an “athletic instructor.” Clearly, some of his instructing took place on the pitcher’s mound. His service awards included the American Theater Ribbon, the Good Conduct Medal, the Meritorious Unit Award, and the World War II Victory Ribbon. His final mustering-out pay was $265.92, including compensation for his travel costs to return home to Newton.14

Less than a month after his discharge, England was in Newark making his debut on the mound for the Eagles. His first start, at Ruppert Stadium on August 15, 1946, was not a memorable game for England or the Eagles. The game was scheduled on the same day as the Negro League All-Star Classic at Griffith Stadium in Washington, three days before the East-West Game was to take place at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Eagles stars Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Leon Day, and Lennie Pearson were absent from the lineup; they were slated to play in the Washington and Chicago games. England and the Eagles lost to the Memphis Red Sox, 11-4. An account of the game in the Atlanta Daily World noted that in the fourth inning the Red Sox “launched their bunting attack and combined six hits, along with three Eagles errors to score eight runs and clinch the contest.”15 The Chicago Defender also noted that the “sensational bunting attack” by Memphis was what won the game.16

On August 19, the day after the Comiskey Park game, England made his second start for Newark. The outcome again was not in his favor: a loss to the Baltimore Elite Giants, 7-1, in the first game of a doubleheader. England gave up 12 hits and his teammates committed five errors. He walked five and made a wild pitch before a crowd of 3,000 at Bloomingdale Oval Park in Baltimore. (Today this field is known as Leon Day Park, named in honor of the former Negro League standout and England’s teammate and leading pitcher for the 1946 Eagles.)

On September 1 the Eagles were in first place in the second half of the season with a record of 14-3. Two of the three losses were charged to England. By then England was no longer with the team. In all likelihood he had been hired by the Eagles to help replace the missing players. After Doby and the others returned from their all-star appearances, England was released. He headed back to Raleigh and re-enrolled in Shaw University. Although it appears that his Negro League career ended with those two Newark losses, some newspaper articles decades later said that England also pitched for the Philadelphia Stars. Even the Baseball in Wartime website links him to the Stars.17 While these assertions are not beyond the realm of possibility, no box scores and/or game summaries exist to support them.

After his stint in the military and his brief career with the Eagles, England resumed his life as a student-athlete on the Shaw Bears’ 1947 and 1948 championship football and baseball teams. He was the team captain and place kicker for the Bears when they won the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association football championship by defeating South Carolina A&T in the title game in Washington, DC.18 In 1948 England was the team captain and most valuable player for the Shaw team that captured the CIAA baseball crown. He also played basketball at Shaw and was an active member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. But one has to wonder how England was eligible to play collegiate baseball after his stint, albeit brief, with the Eagles. This is especially puzzling given this entry in the 1948 Shaw University yearbook: “We find Charles Macon England playing hand to hand with Jackie [Robinson] on the world’s greatest baseball team.”19 The yearbook’s writers were likely referring to Jackie Robinson’s All-Stars, who barnstormed across the country in 1947, the roster including England’s former Eagles teammate, Larry Doby.

England graduated from Shaw University in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree. He was recognized for his academic and athletic accomplishments with a biographical entry in Who’s Who in American Colleges and Universities. England’s nickname at Shaw was “Life,” and he “willed” his ability to “keep cool” while pitching to an underclassman. But England was not done with baseball. After graduation, he left Raleigh and picked up a pitching gig with the North Carolina Twins, a semipro team based in Winston-Salem and playing in the Carolina Baseball Association. He had played in the same league in 1940 when he appeared on the roster for the Raleigh Grays. On July 10, 1949, he took the mound for the Twins in a game against the Asheville Black Tourists. He was billed as the “well known former pitcher for Shaw University and later the Philadelphia Eagles [sic].”20

In the fall of 1949 England was hired to teach science and physical education and coach football at W.A. Pattillo High School in Tarboro, North Carolina. He was on the faculty at Pattillo through 1958 and continued to play baseball during his summer breaks. On April 16, 1950, described as a “former Shaw star who now plays with the Chicago American Giants,” he was scheduled to pitch three innings for the Raleigh Grays in a charity game against the Central Prison Giants.21 That same month, England was among “six collegians” who joined the Giants in their spring-training camp in Columbus, Mississippi.22 His tenure with the team was brief and likely ended shortly after the team broke camp in Mississippi because his name was not mentioned again that season as part of the Giants’ regular lineup.

The 1950s brought many changes to England’s personal and professional life. As a newly minted college graduate, he embarked on what would be a long career as an educator and high-school sports coach. In 1951 he pitched for two semipro baseball teams in North Carolina. In May he took the mound for the semipro Rocky Mount All-Stars. By June he was pitching for the Asheville Blues, formerly of the Negro Southern League. England was touted as an all-star twirler for the Blues and “one of the top hurlers in Negro baseball.”23 Given that Rocky Mount and Asheville are more than 300 miles apart, it is unlikely that he played in too many games.

England’s most remarkable year in baseball was 1952, when he coached his Pattillo High School baseball team to the North Carolina state championship.24 He also garnered headlines for integrating the Rocky Mount Leafs of the Class-D Coastal Plain League. He was signed to a contract with the Leafs by owner Charles Franklin “Frank” Walker, an outfielder for five seasons between 1917 and 1925 for the Detroit Tigers, Philadelphia Athletics, and New York Giants. Walker’s motivation for integrating the Leafs was more of an effort to boost attendance than a brave challenge to racism and Jim Crow, as evidenced when he announced that England would not travel with the team, and would pitch only at home in Rocky Mount.25

Walker’s decision to use England to integrate the Rocky Mount Leafs was not a random choice. England was well-known in the community for his play in the Negro Leagues and semipro circuits, his meritorious military service, his college baseball triumphs at Shaw University, and his roles at a teacher and coach at Pattillo High School. Howard Criswell Jr., a white sports columnist for the Rocky Mount Telegram, wrote that Walker was “not averse” to signing an African-American player, but that “finding one who would be able to take the proper attitude in playing and have the ability” was the challenge.26 According to Criswell, Walker “was not the first one to look at England. … [T]he St. Louis Browns showed a great deal of interest in [England] and had him at a tryout camp they held in Asheville.”27 Criswell said that England turned down a chance to play for the Browns because it would have “interfered with [his] coaching at (Pattillo),” and that after his debut game, England was emotional, understood the historic importance of the moment, saw his chance with the Leafs as a “great honor,” and did his best to “live up to the code of the club and the league. …”28

England made two starts for Rocky Mount. Things did not go well. In both outings, he was knocked out in the fourth inning. For his debut, on June 18, 1952, England stood on the mound before nearly 3,100 boisterous fans, nearly one-third of whom were African-Americans.29 He struck out the first Kinston Eagles batter and retired the second on a routine fly ball. But the third Kinston batter, Herb Grissom, blasted a home run and then the flood gates were wide open. By the time England got the hook in the fourth inning, the Eagles had scored 16 runs, not all of them earned. England was understandably nervous and his teammates didn’t do much to help. The Leafs fielders made three errors in the first four innings. There were also a variety of distractions including a pregame beauty contest, multiple arguments between players, managers, and umpires, and a “negro boy” described as an “illegal person,” who broke the rules by warming up a Kinston player on the field.”30

For England’s second start, on June 24 in Rocky Mount, against the Tarboro Tars, the crowd was noticeably smaller – about 2,000. England had a better outing, giving up six hits in four innings but the Leafs lost, 3-2. And despite his marked improvement over his first outing, two days later he was released. Walker declared that “England didn’t have enough on the ball to pitch in the Coastal Plain League.”31 England brushed off being cut from the team by saying that he was treated fairly, was appreciative for the opportunity, and in short order was planning to leave Rocky Mount for New York University, where he was working on a master’s degree in physical education.32 R.D. Armstrong, in his “News About Negroes” column in the Rocky Mount Telegram, wrote, “England’s short stay here was a credit to himself, his race, and to organized baseball and his anxiety to get in school for the remaining summer months is indicative of his determination to go forward.33 (Within days Walker signed another African-American pitcher, Lafayette Stallings, a native of Nash County, North Carolina. Like England, Stallings did not win a single start with the Leafs and was likewise released.

Charles England was the first African-American to play for the Rocky Mount Leafs but was not the first to be signed by a Coastal Plain League team. That credit went to Charlie T. Roach, a 29-year-old graduate of Winston-Salem Teachers College (today Winston-Salem State University), who made his debut as the first black player for the New Bern Bears on June 10, 1952, eight days before England’s debut,34 and was gone after playing in one game. England and Roach had much in common. Both were grandsons of slaves and lifelong residents of North Carolina. Each served in the Army during World War II, earned bachelor’s degrees at historically black colleges, attended graduate schools, and had successful careers as educators.

England’s and Roach’s fleeting tenures in the Coastal Plain League received similar coverage by the white press. The Rocky Mount Telegram’s Criswell wrote that England “didn’t get rattled” by the large crowd at his debut game and that “Everyone in the stands were behind him.”35 Criswell added that England was not permitted to share the locker room with his white teammates and that there were “only a few minor boos.” The columnist’s sanitized perception of England’s debut did not go unchallenged. Criswell neglected to mention that some Leafs’ players refused to take the field with an African-American. A “letter to the editor” by a white writer defended England’s poor showing by noting, “(T)he Rocky Mount team presented a makeshift lineup with a pitcher playing left field and a third baseman – who last year fielded like a sieve and batted less than .200 – filling in at shortstop.”36 The letter writer summed up his disgust with the uncritical press coverage of England’s performance by adding that he heard “one Negro fan [comment] quite bitterly that Bob Feller couldn’t have won with such a team behind him.”37 White sportswriters made similar assumptions regarding Charlie Roach’s one-and-done appearance. Local newspapers reported that Roach, in his performance for New Bern, “fitted into the club without friction.” Reality was quite different.38 Roach endured racial slurs and boos from the majority white crowd and was sold three days later to the Danville Leafs of the Class-B Carolina League.39 England and Roach made headlines in the summer of 1952 for breaking the color barrier for their respective teams. Their performances generated a momentary spike in gate receipts and public interest, but in the end, they were used for little more than a failed publicity stunt and then were summarily dismissed. The average attendance at Leafs games in 1952 had slumped to just 600 and Frank Walker predicted that the Coastal Plain League would fold and fail to field any teams in 1953.40 And he was right.

After his brief career in the Coastal Plain League, England returned to his teaching and coaching duties at Pattillo High School in Tarboro.41 But he did not quit baseball. Through the 1950s he sporadically pitched games in local leagues. One of his last appearances on the diamond was in 1957, when he managed the Rocky Mount native and Hall of Famer Buck Leonard and an aggregation called the Eastern North Carolina All Stars in an exhibition game in Tarboro against the Kansas City Monarchs. He left Pattillo for teaching and coaching assignments at Dunbar High School in Lexington, North Carolina, until the school closed in 1967. England coached Dunbar’s baseball and football teams to numerous titles and in 1960 was named Coach of the Year in Davidson County, North Carolina.42 In 1968 England was hired to teach and coach at the integrated Lexington Senior High School, where he enjoyed similar success as an assistant football coach and head baseball coach.

The 1960s also marked a major change in England’s personal life. On April 15, 1960, he married Julia May Chisholm in Mecklenburg, North Carolina. She had graduated summa cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in elementary education from Johnson C. Smith University in her hometown of Charlotte, North Carolina. Like her husband, she went to New York City for her graduate education and earned a master’s degree at the Teachers College of Columbia University. She was a teacher for 32 years when she retired in 1985. Charles and Julia raised three children in Lexington. They had something else in common – their commitment to the civil rights movement. Both were members of the NAACP and activists for racial equality and social justice in their community. In the early 1990s, Charles England tried unsuccessfully to convince the Davidson County Commission to recognize MLK Day as an official holiday for county employees. After England’s death in 1999, members of a committee created by England continued the fight for recognition. One committee member said of England that he “taught me how to walk with dignity” and that he saw England as a “replica” of Dr. Martin Luther King.43 Another three years elapsed before Davidson County acknowledged MLK Day in 2002 as a legitimate holiday, one of the last of North Carolina’s 100 counties to do so.

After England retired from teaching and coaching in the 1980s, he received numerous awards and accolades for his athletic achievements and dedication to education and serving the community. In 1982 he was inducted into the Shaw University Hall of Fame. In 1988 he received the A. Odell Leonard Humanitarian Award from the Lexington Civitan Club. Even after his death in 1999, England continued to be honored. Less than a month after he died, the Dunbar Intermediate School, where he began his teaching career, was renamed the Charles England Intermediate School.44 In 2000 he was inducted into the North Carolina High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame.45 When a new Charles England Intermediate School was built in Lexington in 2008, his son, Charles Macon England Jr., recalled one of his father’s favorite sayings: “A man never stood so tall as when he stooped to help a child.”46 In 2016 the nonprofit Charles and Julia England Foundation was created to provide grants for teachers who are engaged in “creative learning opportunities for students” in the Lexington city schools.47 The theme for the Charles England school and foundation is based on another frequent exhortation by Coach England – “Be somebody.”

Charles M. England died on January 23, 1999, in Salisbury, North Carolina. He was 77 years old. He was survived by his wife, Julia, and their three children. Only one of his siblings survived him, his sister Marion Evelyn England Burgin, who lived her entire life in Catawba County. Julia Chisholm England died in 2015. Charlies and Julia are buried in Forest Hill Memorial Park in Lexington.

Charles Macon England lived a dignified and meritorious life in difficult times. In spite of the barriers placed before him in the Jim Crow South, he graduated from college, excelled in his academic and athletic pursuits, and helped break down racial barriers in US Army baseball teams and the Coastal Plain League. England had a dismal two-start career with the Newark Eagles in 1946 but was not daunted by the defeats. He moved forward in his life and made quantifiable differences in the lives of hundreds of students and student-athletes who benefited from his tutelage and tried their best to “be somebody.” England was a sterling role model in the classroom and on the baseball diamond. It is quite possible that he is one of the most lauded former Negro League players in history who was not a superstar on the mound but was a stellar member of society as a whole. Charles England did not make a major mark in the Negro League record books, but his name, his wide-ranging contributions, and his reputation are still very much present.

Notes

1 US Census Bureau, 1940 Census.

2 Ibid.

3 “Base Ball,” Newton (North Carolina) Enterprise, July 14, 1883: 3.

4 “Base Ball,” Enquirer Southerner (Tarboro, North Carolina), October 2, 1874: 4.

5 “Locals,” Newton Enterprise, June 5, 1903: 3; “Locals,” Newton Enterprise, April 15, 1909: 3; “Locals,” Newton Enterprise, April 11, 1912: 2; “Locals,” Newton Enterprise, March 27, 1913: 3.

6 Betty J. Jamerson, School Segregation in Western North Carolina: A History, 1860s-1970s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 213.

7 Jamerson, 215.

8 World War II Draft Registration Card, 1942, for Charles Macon England, Order No. 10170.

9 Wanda E. Wakefield, Playing to Win: Sports and the American Military, 1898-1945 (Albany, New York: State University Press of New York, 1997), 128.

10 Ernest R. Rather, “Camp Lee Training Band,” Chicago Defender, September 15, 1945: 11.

11 “Lexington Dunbar Coach Speaks at Final Carver Sports Banquet,” Daily Independent (Kannapolis, North Carolina), April 30, 1967: 11-A.

12 “Wilkes-Barre Nine Trips Camp Lee,” Washington Post, April 11, 1946: 13.

13 “Rally by Camp Lee Defeats Binghamton Nine by 4-3 Count,” Richmond (Virginia) Times Dispatch, April 25, 1946: 18.

14 US Army, Enlisted Record and Report of Separation Honorable Discharge, for Charles Macon England, July 17, 1946.

15 “Memphis Red Sox Top Newark Eagles, 11-4,” Atlanta Daily World, August 15, 1945: 5.

16 “Memphis Trims Eagles,” Chicago Defender, August 17, 1945: 11.

17 baseballinwartime.com/negro.htm.

18 1948 Shaw Bear Yearbook (Shaw University), 54. The CIAA is a collegiate athletic conference of mostly historically black colleges.

19 1948 Shaw Bear Yearbook, 33.

20 “Asheville Black Tourists Face N.C. Twins Today,” Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, July 10, 1949: 36.

21 “Raleigh Grays Play Prison Squad Today,” Raleigh News and Observer, April 15, 1950: 19.

22 “Gate Attractions Sought on College Campuses,” Atlanta Daily World, April 18, 1950: 3.

23 “Firefighters Play Blues,” Jersey Journal (Jersey City, New Jersey), June 22, 1951: 17.

24 R.D. Armstrong, “News About Negroes,” Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Telegram, June 22, 1952: 5.

25 “Leafs Lose but Turkey Protests Game in Ninth,” Rocky Mount Telegram, June 19, 1952: 14.

26 Howard Criswell Jr., “Sports Talk: The First One,” Rocky Mount Telegram, June 17, 1952: 10.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 “Full House,” Rocky Mount Telegram, June 19, 1952: 15.

30 Ibid.

31 “England Released,” Rocky Mount Telegram, June 27, 1952: 10.

32 R.D. Armstrong, “News About Negroes: Two Big Events,” Rocky Mount Telegram, June 22, 1952: 5.

33 Ibid.

34 “Negro Makes Debut in Coastal Plains,” Asheville Citizen-Times, June 10, 1952: 14.

35 Howard Criswell Jr., “Sports Talk: Big Night,” Rocky Mount Telegram, June 20, 1952: 10.

36 W.G. Williams, “Charlie England,” Raleigh News and Observer, July 10, 1952: 10.

37 Ibid.

38 “Negro Makes Debut in Coastal Plains.”

39 Bill Hand, “New Bern Hosted the First Black Player in an All White League,” New Bern (North Carolina) Sun Journal, November 4, 2012. newbernsj.com/article/20121104/Opinion/311049940.

40 “Closed Out,” Rocky Mount Telegram, September 2, 1952.

41 “Monarchs Will Play All-Stars at Tarboro, Raleigh News and Observer, July 3, 1957: 12.

42 “Charlie England Coach of the Year,” Chicago Defender, January 23, 1960: 24.

43 “In Memory of Coach Charles England,” Lexington (North Carolina) Dispatch, January 27, 1999. the-dispatch.com/news/19990127/in-memory-of-coach-charles-england.

44 Deneesha Edwards, “New Charles England Intermediate School Opens,” Lexington Dispatch, August 21, 2008. the-dispatch.com/news/20080821/new-charles-england-intermediate-school-opens.

45 “Charlie England, Lexington Dispatch, September 6, 2002. the-dispatch.com/news/20020906/born-thomasville-may-22-1946.

46 “New Charles England Intermediate School Opens.”

47 besomebodyfund.com.

Full Name

Charles Macon England

Born

September 6, 1921 at Newton, NC (US)

Died

January 23, 1999 at Salisbury, NC (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.