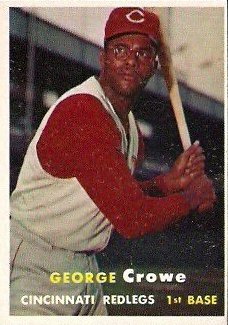

George Crowe

George Crowe was Indiana’s first Mr. Basketball and became a “Big Daddy” to early black players in major league baseball. “Crowe was the most articulate and far-sighted Negro then in the majors,” Jackie Robinson wrote. “Young Negroes turned to him for advice.”1 Yet this splendid athlete and respected leader chose to spend one-third of his long life as far from the spotlight as he could get.

George Crowe was Indiana’s first Mr. Basketball and became a “Big Daddy” to early black players in major league baseball. “Crowe was the most articulate and far-sighted Negro then in the majors,” Jackie Robinson wrote. “Young Negroes turned to him for advice.”1 Yet this splendid athlete and respected leader chose to spend one-third of his long life as far from the spotlight as he could get.

George Daniel Crowe was born in Whiteland, Indiana, on March 22, 1921, the fifth of ten children. The youngsters had to pitch in on the family farm in Franklin, about 20 miles south of Indianapolis. Their father died when George was in his teens. The oldest brother, Ray, became the basketball coach at Crispus Attucks High in Indianapolis, where he and his star player, Oscar Robertson, won back-to-back state championships.

Franklin High had no football or baseball team, but George was a left-handed first baseman on the softball team. He recalled, “What baseball playing I did was usually on Sundays in the summer.”2 He didn’t play basketball until his junior year, when the new coach of the junior varsity asked the tall teenager, “Crowe, how come you’re not out for basketball?” Crowe replied, “They don’t allow no black players to play at Franklin.” The coach told him, “You can play for me.” Crowe remembered that the JV “kicked the shit out of the varsity,” but some varsity players didn’t want him as a teammate. The team captain told them, “Listen, Crowe can play more basketball than all you guys put together.”3

The Franklin High Grizzly Cubs played for the state championship in 1939, Crowe’s senior year. A muscular six-foot-two center, he scored 13 of the Grizzlies’ 22 points as they lost to a Frankfort team led by future North Carolina State coach Everett Case. When a committee of five high school principals picked the tournament’s outstanding player, they named a white boy from a team that didn’t make the finals. Several white sportswriters condemned the choice as a sorry legacy of the state’s history; Indiana had been a Ku Klux Klan stronghold earlier in the century. John Whitaker of the Hammond (Indiana) Times wrote, “George Crowe was reminded by five little men that his color wasn’t right.”4

Coincidentally or not, the Indianapolis Star invited its readers to vote for an all-state team for the first time. George Crowe, the only black player on a small-town team, finished first with 48,375 votes out of more than 103,000 cast. As the people’s choice, he was named Indiana’s Mr. Basketball, an award that has been given ever since to the top high school player in the state’s favorite sport.5 Franklin coach Fuzzy Vandivier called Crowe “the best money player I have ever seen.”6

Crowe and six of his brothers and sisters went on to Indiana Central College, an integrated school in Indianapolis founded by the United Evangelical Brethren church. (It is now the University of Indianapolis.) George was a four-year starter in basketball. The ICC Greyhounds won 30 consecutive games and went undefeated in the 1941-42 season. Crowe played first base and outfield on the baseball team and competed in several track and field events. There was no football team, but he helped organize an intramural touch football league. When the 1943 baseball season was canceled because of the war, the campus newspaper, The Reflector, lamented, “Gone is the spectacular, spine-tingling sight of George Crowe and company circling the bases at breakneck speed or pulling down long flies.”7

During his senior year Crowe enlisted in the U.S. Army Reserve, and he reported for active duty after his 1943 graduation. The army was segregated, with black units commanded by white officers. At Camp Lee, Virginia, he starred on the baseball and basketball teams, but not for long. During an assembly, a white colonel “said something about ‘a nigger,’” he recalled, “and I got up and walked out.” Another officer came to Crowe’s barracks to explain that the colonel was a Southerner, and that’s the way he talked. Crowe refused to accept an apology. He was quickly transferred to Fort Hood, Texas, a staging point for troops headed overseas.8 The ugly incident turned out well; he met his future wife, Yvonne Moman, in Texas.

He spent more than a year in Asia as a lieutenant in the 373rd Quartermaster Truck Company. The unit hauled supplies from India to China through mountain snows and stifling tropical jungles along the Ledo and Burma roads. “Each trip took 28 days from Burma to Kunming,” he said. “And each time we flew back in three hours.”9

Crowe married Yvonne after he was discharged in 1946. They had two daughters, Adrienne and Pamela. One night he and his wife went to a movie in his hometown. An usher ordered them to leave their seats because black patrons were only allowed in the balcony. Crowe refused. The usher backed off and, as Crowe told it, the theater dropped its segregation policy a week later.10

Since he had gone straight from college to the army, Crowe had no civilian job waiting for him. He went to California with one of his brothers and began taking classes at Compton Junior College, but quit when he saw a chance to become a professional athlete. He tried out for the Los Angeles Red Devils, a touring basketball team, and made the squad. He played forward opposite Jackie Robinson, who had just finished his first year in white baseball at Montreal. Future major leaguer Irv Noren was in the backcourt. When the Devils went broke after a few months, Crowe joined the New York Rens, a storied black basketball power since the 1920s. The team was originally known as the Harlem Renaissance Five because they played at the Renaissance Ballroom in Harlem. He said, “The Harlem Globetrotters got the publicity, but the Rens had the team.”11

The Rens traveled the country in a bus called “The Blue Goose,” sometimes playing twice a night and racking up more than 100 games a year. In Crowe’s first season they became the first all-black team to appear in New York’s Madison Square Garden, where he scored 19 points. In 1948 they played for the championship of the World Professional Basketball Tournament in Chicago against the NBA’s Minneapolis Lakers. The tournament was the pinnacle of pro basketball; the NBA was just getting started. When the Rens’ center, Sweetwater Clifton, picked up three fouls, the 6’2″ Crowe had to guard the Lakers’ 6’10″ George Mikan, the most dominant player of his time. Mikan scored 40 points, but one newspaper account said Crowe did a better job on him than Clifton. The Lakers came from behind to win, 75-71.12

Crowe always maintained that basketball was his best sport, and he enjoyed it more than baseball because there was more action. But professional basketball was on shaky financial ground in the 1940s. The Rens were Crowe’s entrée into baseball. Their business manager arranged for him to try out with the New York Black Yankees baseball team after the basketball season ended in the spring of 1947. The Black Yankees played their Negro National League games at Yankee Stadium. Partial statistics compiled by SABR’s Negro Leagues Research Committee show him hitting .305 with a .376 slugging percentage in 141 at bats in 1947. A news story said he hit .338 the next year, but no further details are available. In September 1948 he played in the all-star “Dream Game” against the Negro American League in Yankee Stadium. During his time with the Rens and Black Yankees he moved his family to the New York City area. He also began wearing glasses because he had difficulty seeing the ball.

The Negro National League disbanded before the 1949 season as its fans switched their allegiance to black players in the formerly white majors. Crowe recalled, “We had hope once Jackie got in; everybody started taking it seriously.”13 Effa Manley, owner of the Negro League Newark Eagles, recommended Crowe to the Boston Braves and the defending National League champions signed him after a spring tryout. It has been reported that he was the first black player in the Braves organization, but another Negro Leaguer, Weldon Williams, may have signed earlier in the spring.14

Crowe was 28 years old when he broke into organized baseball, but he told the Braves he was 26. His birth date was listed as 1923 throughout his career. For the next three years he overpowered minor league competition. In his first week with Pawtucket in the Class B New England League in 1949, he hit home runs in two consecutive games. He finished the season batting .354 with 12 homers. In the fall he joined Jackie Robinson’s barnstorming team before playing for the Harlem Yankees in the American Basketball League. Moving up to Single A Hartford in 1950, he won the Eastern League batting championship at .353, hit 43 doubles and 24 homers, and was named MVP. During the winter he won his second batting title of the year with a .375 average for pennant-winning Caguas in the Puerto Rican League.

The Braves promoted Crowe to Triple-A Milwaukee in 1951. But authorities in Austin, Texas, where the Brewers spent spring training, served notice that local law prohibited blacks and whites from playing on the same field. The Braves instead brought Crowe to their major league camp in Bradenton, Florida. His third minor league season produced more spectacular results: a slash line of .339/.429/.567 (batting average/on-base percentage/slugging percentage) while leading the league in hits, doubles, total bases, and RBI. He was a unanimous choice for the American Association all-star team and was named the league’s outstanding rookie.

Clearly he was major-league ready, but he had no place to play. Boston already had a powerful left-handed first baseman, Earl Torgeson, who had hit 24 homers in 1951. The 31-year-old rookie (who was 29, as far as the team knew) made the Braves roster in 1952, but he thought manager Tommy Holmes favored Torgeson because the two had been roommates. In fact, Torgeson was an established major leaguer and Crowe was not. Crowe’s Milwaukee manager, Charlie Grimm, who replaced Holmes in June, found playing time for both first basemen until August, when Crowe was optioned back to Milwaukee. It was a shock; his .258 batting average was second best on the Braves, while Torgeson was hitting slightly above .200. The official explanation was that Boston was buried in the second division and wanted to give Milwaukee a big bopper for its American Association pennant drive. Harold Kaese of the Boston Globe sneered, “The release of Crowe looks like a case of the Braves being a farm team for Milwaukee.”15 (Some clubs enforced a quota of no more than two black players, but that was not a factor when Crowe was sent down; the Braves had only one other African American, Sam Jethroe.)

The Braves traded Torgeson in February 1953 to acquire a new regular first baseman, Joe Adcock, in a four-team swap. That set the tone for Crowe’s career. His clubs never regarded him as an everyday player, perhaps because he was considered a poor fielder. Crowe spent the 1953 season as a pinch hitter, batting only 45 times with a .286 average, as the Braves climbed to second place in their new home, Milwaukee.

The Braves sold him to their Toledo farm club after the season. In 1954 he again proved he was too much for Triple-A. He led the American Association in hits, doubles, RBI, and total bases, belting 34 home runs with a line of .334/.394/.582. The Braves bought him back to keep from losing him in the draft.

Baseball was Crowe’s year-round job during the 1950s. He barnstormed in the fall with teams headlined by Roy Campanella and Willie Mays, then moved on to the Caribbean during the winter. In the 1954-1955 season he played for Santurce, Puerto Rico, on one of the strongest winter league teams in history. The outfield included Mays, 20-year-old Roberto Clemente, and Negro League veteran Bob Thurman. Don Zimmer played shortstop, Negro League star Bus Clarkson was at third, and Sam Jones and local hero Ruben Gomez led the pitching staff.

The Braves gave Crowe his first chance to play regularly in 1955 when the Giants’ Jim Hearn broke Adcock’s arm with a pitch on July 31. Crowe played every game after that, batting .281/.374/.495 with 15 homers in 354 plate appearances. His adjusted on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS+) was 133, an all-star level performance.

In 1956 Milwaukee brought up a new first baseman, Frank Torre, who had hit .327 in Triple-A. He was also left-handed and eleven years younger than the 35-year-old Crowe. By this time Crowe weighed well over 200 pounds and had lost the speed he showed in his youth. Just before opening day he was traded to Cincinnati. The Redlegs needed insurance because their slugging first baseman, Ted Kluszewski, was overweight and suffering from back and hip pain. (As part of the deal Milwaukee acquired minor leaguer Bob “Hurricane” Hazle, whose late-season batting splurge sparked the Braves in the 1957 pennant race.)

When manager Birdie Tebbetts put Crowe in the lineup to replace Kluszewski, Cincinnati fans pelted him with boos. In his first game he went 1-for-5, struck out twice, and made an error. “I hope they all come back tomorrow,” he said. “I’ll show them something.” The next day he slammed two home runs and a triple. The Redlegs won seven straight games and Tebbetts promised, “He’ll stay in the lineup as long as we keep winning.”16 That wasn’t long. Kluszewski lost weight and got his job back. Crowe hit 10 homers with a .798 OPS in 157 plate appearances.

Crowe accused Tebbetts of sabotaging the club’s pennant hopes because he didn’t want Brooks Lawrence to be a 20-game winner. Years afterward Crowe said, “Birdie Tebbetts came out one day and told someone, ‘Ain’t no black man’s going to win 20 games for me.’ And he refused to pitch Lawrence after he got 19 wins.”17 Lawrence won his nineteenth on Sept. 15, when the third-place Redlegs were two games behind Milwaukee and Brooklyn, and didn’t start again. The club lost four straight and fell further back. Lawrence relieved five times in the last two weeks of the season, but only once when he had a realistic chance for a victory; he gave up the winning run in a tie game. (In fairness to Tebbetts, another of his black players, Frank Robinson, wrote, “Birdie was like a father to me.”18)

Kluszewski’s back didn’t improve over the winter. He was able to start only 23 games in 1957, giving Crowe the most extensive playing time of his career at age 36 (officially 34). He was batting .301 with 28 home runs on August 14 before he hurt his knee and played on one good leg for the last six weeks. “I was never the same after that,” he remembered.19 He hit only three more homers and finished with a line of .271/.314/.504—not quite Kluszewski territory, but well above average.

That summer Cincinnati fans stuffed the ballot boxes for the All-Star Game. Seven of the Redlegs’ eight regulars were elected to start. When it appeared that Crowe was going to beat Stan Musial for the first-base slot, the Cincinnati front office urged the fans to vote for Musial. Commissioner Ford Frick intervened, dropping Crowe and outfielders Gus Bell and Wally Post from the starting lineup in favor of Musial, Willie Mays, and Henry Aaron. As a result, fans lost the right to vote for all-stars for more than a decade.

After the 1957 season the Redlegs traded Kluszewski, one of the most popular players in their history, but they were not ready to hand his job to Crowe. They acquired left-handed veteran first baseman Dee Fondy from Pittsburgh. They also picked up Steve Bilko, a Kluszewski-sized right-handed hitter who had clubbed 55 and 56 home runs in the previous two years in the Pacific Coast League, but had failed in previous big league trials. Crowe opened the 1958 season in a platoon with Bilko. Tebbetts predicted he might get 45 homers out of the pair, but Bilko was traded in June. Cincinnati claimed former AL Rookie of the Year Walt Dropo on waivers to share time with Crowe.

Crowe was chosen for his only all-star team in 1958 as a reserve, but did not play in the game at Baltimore. Although his batting average stayed steady at .275, his power disappeared. He managed only seven home runs in 393 plate appearances and slugged just .400. Because of his bad knee, he said, “I couldn’t twist. I just had to hit with my arms.”20 In October Cincinnati traded him to St. Louis in a six-player swap.

The 1959 Cardinals had two young left-handed first basemen, Bill White and Joe Cunningham, but they had to play outfield to make way for the old first baseman, Stan Musial. At 38, Musial was four months older than Crowe. Crowe’s job was pinch-hitting. He hit four pinch home runs in both 1959 and 1960. In 1960 the eleventh pinch homer of his career set a major league record. When he retired he was said to be the record-holder with 14; Retrosheet and Baseball-Reference.com data give him 16, a mark since surpassed by several others. During his nine-year career Crowe hit .274/.327/.509 in 312 plate appearances as a pinch hitter.

The Cardinals had been latecomers to racial integration; their first black player, first baseman Tom Alston, did not arrive until seven years after Jackie Robinson. By 1959 St. Louis had Bill White playing regularly, young Curt Flood serving as White’s late-inning caddy in the outfield, and Marshall Bridges and rookie Bob Gibson on the pitching staff. Wherever he went, Crowe was the acknowledged leader of the African American players, most of them much younger than he. Vada Pinson, a rookie with Cincinnati in 1958, said Crowe “took me right under his wing. He came up to me and said, ‘If there are any problems, you come to me. I’m your father, your big daddy up here.’”21 Bob Gibson remembered that Crowe “was more like a dad and teacher than teammate, and most of what he counseled me on had nothing to do with playing the game.”22

Crowe told Sports Illustrated’s Robert Boyle, “I like to see everybody keep their nose clean. And when you have fellows who are coming along who are new to this, I’m glad to give guidance.” He watched out for young black men no matter what uniform they wore: “If I knew a kid coming up with the Braves, I’d say to [Bill] Bruton, ‘Look out for this kid. Show him the places to eat. Don’t leave him stand in the hotel. Take him to the movies. Find out what he likes to do.’ “23

Bill White said Crowe “was a very wise fellow who’d been through it all and, in the background, he led us in the integration movement [of spring training cities] in Florida before the Civil Rights Act.”24 In 1961, when Crowe was entering his final season, black Cardinals players seethed when their white teammates were invited to a Chamber of Commerce breakfast at a whites-only hotel in St. Petersburg. The next spring the team rented a motel where all the players and their families could stay together. Decades later Crowe reflected on the racism he had endured: “Even though you wanted to put it aside, you couldn’t. It couldn’t be put aside. Putting it aside was doing your best to ignore it, and that wasn’t easy, either. That’s what you had to do. You had to play through it.”25

Crowe commanded respect from white teammates as well. By popular consent, he served as the judge of the Cardinals’ kangaroo court, meting out small fines for offenses such as missing the team bus or missing the cutoff man. He impressed Musial with how hard he worked to stay in shape. He told Musial, “The more time you spend on the bench the harder you’ve got to work to be ready when you’re called.”26

The 40-year-old Crowe pinch-hit seven times in the early weeks of the 1961 season, with just one hit. The Cardinals released him on May 10, but offered him a job as a player-coach with their AAA farm club. He worked with young catcher Tim McCarver. “George Crowe changed my life, certainly my life in baseball,” McCarver declared. “My whole batting stance from then on was based on everything George Crowe taught me.”27 After the season the Cardinals hired Crowe as a scout, working from his home in Springfield Gardens, New York, and he served as a spring training coach.

Crowe gave up life on the road as a scout after two years. Baseball turned its back on most African American players after they retired. Resentment was building in the 1960s, with Jackie Robinson leading the push to hire more black coaches and give a black man a chance to manage. Crowe’s name always appeared near the top of every list of men who were qualified for a manager’s job.

Resentment turned to rage in 1968, when Commissioner William Eckert declined to cancel Opening Day games after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4. The Pittsburgh Pirates, black and white, threatened to boycott their opener, and all teams eventually called off the games on April 8 and 9. To quell the anger, the commissioner decided to hire a black assistant. Ex-pitcher Joe Black polled his cohorts and found that Crowe was the favorite candidate, but the commissioner chose Monte Irvin, who had been a more prominent player.

Away from sports, Crowe was adrift. He sold life insurance, worked for Pan American World Airways in California, and then returned to New York to teach physical education and coach the freshman baseball team at a high school. He and his wife divorced. When a doctor told him he was developing an ulcer, he blamed the stress of trying to teach kids who weren’t interested in learning.

As he reached his fiftieth birthday in 1971, Crowe dropped out. He moved to the back side of beyond, to the foothills of New York’s Catskill Mountains. His home, near the hamlet of Long Eddy, was a log cabin he called “The Jackass Inn,” seven miles from the nearest paved road. It had no heat, electricity, running water, or telephone. The only way to his front door was a long hike up a rocky slope. Some described him as a hermit, but he stayed in touch with family and friends and was willing to talk to any reporter who took the trouble to find him.

Crowe lived as a mountain man for more than 30 years. “In these hills I’m free,” he told a visiting writer. “I don’t have to punch anyone else’s time clock. I was sick of people and all the nonsense of our society.” Although he had enjoyed hunting and fishing, he became a vegetarian for a while, growing most of his food. He stopped drinking and gave up white flour and sugar. The powerful athlete morphed into a skinny old man with a white beard. “Here, I make my own rules,” he said. “I look at birds when I want to, eat all the raw fruits and vegetables I want, don’t have to chew tobacco any more to calm my nerves and think any way I want. Now I can honestly say, ‘Crowe isn’t anyone’s slave anymore.’”

His baseball pension provided enough to support his stripped-down lifestyle. In his philosophy, “You’ve got to have a sense of peace. I get that when I see the sun come over those hills.”28

Crowe stayed in his refuge until was past 80, when his daughter Adrienne persuaded him to move in with her near Sacramento, California. In 2005 he told the New York Times’s William C. Rhoden, “I have two artificial knees, artificial hip, pacemaker and no brains.”29

A series of strokes put him in an assisted living center in his last years. In December 2010 doctors told him he was near the end. On Christmas Eve he sat with a friend sampling Crown Royal Black whiskey while watching a video of his favorite singer, Ella Fitzgerald.30 He died on January 18, 2011, in Rancho Cordova, California, two months short of his ninetieth birthday.

Crowe was elected to Indiana’s basketball and baseball halls of fame. His brother Ray is also a member of the basketball shrine. In 2012 their alma mater, the University of Indianapolis, named one of its dorms Ray & George Crowe Hall. University President Beverley Pitts said, “These men distinguished themselves, both here at the university and in later life, not only as great competitors but as mentors and role models for character, sportsmanship and citizenship.”31

Notes

1 Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (repr. Brooklyn: Ig Publishing, 2005), 66.

2 The Sporting News, March 26, 1952, 2.

3 http://www.blackfives.com/george-crowe-part-1-life-place-time/, accessed April 10, 2012. Claude Johnson’s website, Black Fives, is an invaluable source about Crowe’s life away from baseball.

4 Reprinted at http://www.blackfives.com/george-crowe-part-2-life-place-time/, accessed April 10, 2012.

5 Indianapolis Star, undated 1939 clippings in the George Crowe file at the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame, New Castle, Indiana.

6 Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame, http://www.hoopshall.com/hall-of-fame/george-crowe/?back=HallofFame, accessed February 27, 2012.

7 The Reflector, March 1943, provided by University of Indianapolis archivist Christine H. Guyonneau.

8 http://www.blackfives.com/george-crowe-part-3-life-place-time/, accessed April 10, 2012.

9 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 28, 1959, in Crowe’s Hall of Fame file.

10 Indystar.com, January 21, 2011, http://www.indystar.com/article/20110121/sports02, accessed February 25, 2012.

11 Bob Pille, “The Insurance Man Pays Off,” Baseball Digest, October 1957, 83.

12 Ron Thomas, They Cleared the Lane: The NBA’s Black Pioneers (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 2004), 8-9.

13 New York Times, October 15, 2005, D2.

14 Sporting News, May 14, 1949, 47.

15 Boston Globe, August 11, 1952, in Crowe’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library.

16 Sporting News, May 9, 1956, 17.

17 New York Post, October 5, 1997, in Crowe’s Hall of fame file.

18 Frank Robinson and Berry Stainback, Extra Innings (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988), 37.

19 New York Post, October 5, 1997.

20 Rick Hines, “George Crowe—an original two-sport athlete,” Sports Collectors Digest, May 27, 1994, 101.

21 Robert Boyle, “The World of the Negro Ballplayer,” Sports Illustrated, March 21, 1960, online archive.

22 Bob Gibson and Reggie Jackson, with Lonnie Wheeler, Sixty Feet, Six Inches: A Hall of Fame Pitcher & a Hall of Fame Hitter Talk About How the Game Is Played (repr. New York: Anchor, 2011), 214.

23 Boyle, “World of the Negro Ballplayer.”

24 New York Daily News, online edition, January 22, 2011, reprinted at www.blackfives.com.

25 Franklin (Indiana) Daily Journal, March 27, 2010, online edition, reprinted at www.blackfives.com.

26 George Vecsey, Stan Musial, An American Life (New York: Random House Digital, 2011), 244

27 Cal Fussman, After Jackie: Pride, Prejudice, and Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes (ESPN Books, 2007), 110.

28 Ed Kiersh, “George Crowe,” Inside Sports, April 1981, 54-55.

29 New York Times, October 15, 2005, D2.

30 Claude Johnson, “RIP George Crowe, the Last of the Harlem Rens,” http://www.blackfives.com/r-i-p-george-crowe-the-last-of-the-harlem-rens/, accessed February 25, 2012.

31 University of Indianapolis press release, http://news.uindy.edu/2012/02/23/new-dorm-name-will-honor-accomplished-alums/, accessed February 23, 2012.

Full Name

George Daniel Crowe

Born

March 22, 1921 at Whiteland, IN (USA)

Died

January 18, 2011 at Rancho Cordova, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.