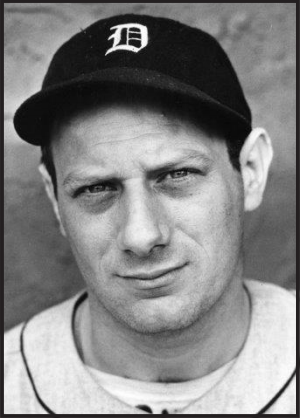

Charlie Fuchs

As World War II began to encroach on major-league baseball teams as well as their minor-league affiliates, doors opened to players who otherwise would have been considered to lack major-league talent. Some who were rejected for military service and classified 4-F became increasingly prime candidates to play in the majors – selected because it was reasonably certain they would not be drafted. Others like Jimmie Foxx, Debs Garms, and Pepper Martin, whose careers in the majors had ended, were brought back to fill out rosters. And still others whose play in the minors never generated interest from major-league teams found themselves reappraised in light of rapidly changing world events. This latter scenario proved beneficial to longtime minor-league pitcher Charley Fuchs when he was purchased by the Detroit Tigers to play during the 1942 season.1 His career began and ended during World War II. During his three years in the majors, Fuchs played for four major-league teams.

Charles Thomas Fuchs, of German descent, was born on November 18, 1913, in Union Hill,2 New Jersey, the son of Robert and Cornelia Fuchs.3 His father, a native of what was then Austria-Hungary, arrived in the United States in 1896 and had become a locomotive engineer. Charles was the second oldest child in the family. Little is known of his early life except that he graduated from Holy Family High School in Union City and subsequently played semipro ball in the area. On February 18, 1931, he married Gertrude Cumiskey. 4 They would eventually have four children. 5

Fuchs’ first appearance in professional baseball was with the Richmond Colts of the Class B Piedmont League in 1937. The 23-year-old right-hander pitched in just one game for Richmond, an affiliate of the New York Giants. The next two seasons Fuchs pitched for the South Boston Wrappers of the Class D Bi-State League. His record in 1939 with South Boston was a creditable 14-10, and it earned him a late-season promotion to the Oklahoma City Indians of the Class A-1 Texas League. There he threw a no-hitter against the Houston Buffalos.6

In 1940, pitching for both Oklahoma City and Beaumont, Fuchs fashioned a 19-13 performance and won a promotion to Buffalo, a Detroit Tigers affiliate in the Double-A International League. Included in his wins with Oklahoma City was a second no-hitter, against the San Antonio Missions. His promotion to the Buffalo Bisons in 1941 proved a downer as Fuchs went 7-13, clearly a disappointing year for the then 27-year-old minor leaguer.7 However, the Tigers invited him to spring training in the spring of 1942.

The Tigers had won the American League pennant in 1940, but had a poor season in 1941, finishing fifth. A significant factor in their performance was the loss of Hank Greenberg to the US Army Air Force early in the year and a pitching staff that was in a state of flux.

Two stalwart pitchers for the 1940 pennant winners, Bobo Newsom and Schoolboy Rowe (a combined 37-8 in 1940) had fallen off to 20-26 in 1941. Hal Newhouser and Dizzy Trout would carve out great records in 1944 and 1945 but had not yet established themselves as bellwether starters on the Tiger staff. Thus, as the 1942 season opened, Detroit was looking to augment their pitching.

Although Fuchs had some rough outings in spring training, overall he performed well enough to make the Opening Day roster.8 He made his first major-league appearance in Detroit’s fourth game of the season, relieving Virgil Trucks in the seventh inning of a game against the St. Louis Browns. While not charged with any earned runs, he gave up hits that allowed inherited runners to score, which eventually proved the difference in a 7-6 Browns victory.

Two days later Fuchs made his first start and impressed with a four-hit 1-0 shutout of St. Louis, gaining his first major-league victory. He stayed in the rotation the next two weeks, winning two more games, although his effectiveness steadily dimmed. On May 4 he went into the ninth inning against the Philadelphia A’s holding a 6-4 lead. With two men on base, Fuchs was relieved by Hal Newhouser, who got the final out, giving Fuchs his third victory. It was the seventh game Newhouser had relieved, all without giving up an earned run. Their respective performances proved consequential to the fortunes of both players.

Two days later, the 21-year-old Newhouser went into the starting rotation, essentially replacing Fuchs. Although Newhouser generated a lackluster 8-14 record, his 2.45 ERA ranked fourth in the league. He was selected for that summer’s American League All-Star team, the first of six times Newhouser was named. Relegated to the bullpen, Fuchs pitched ineffectively in several games, the last of which was against the Chicago White Sox, who victimized him with a seven-run outburst in the ninth inning on May 30. That night he was assigned back to Beaumont. His record for Detroit was 3-3 with a 6.63 ERA. In what remained of the season, Fuchs did well, going 11-4 with a 2.06 ERA in the Texas League. The Philadelphia Phillies saw some potential and purchased his contract from Detroit in March 1943 for the $7,000 waiver price.9

Philadelphia had finished in last place each of the previous five seasons. The Phillies were desperate for pitching. Quite possibly another factor was at work in acquiring him: Teams were becoming increasingly aware of a player’s draft status. That Fuchs was 29 and married with two children (or possibly four children, depending on the source), minimized the chance of his being called into the military.10

Working out of the bullpen and as a spot starter, Fuchs posted several successful outings. On May 20 he shut out the Cubs on four hits in the first game of a doubleheader; Chicago did not fare well in the second game either, as Fuchs’ teammate Al Gerheauser also threw a four-hit shutout. Fuchs pitched well his next start, losing to the Reds 1-0 on a two-out single in the bottom of the ninth inning. His performance after that proved sporadic, probably because of a stiff neck. In early July he was sold to the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association, leaving the Phillies with a 2-7 record and a 4.19 ERA.11

Before Fuchs could report to Toledo, he was purchased by the Browns.12 St. Louis was becoming adept at picking up castoffs and players exempt from military service, a skill that would serve them well with a pennant in 1944. Fuchs pitched in 13 games, strictly in relief, for St. Louis, without a decision.

In early 1944, Fuchs, released by the Browns to the Newark Bears, refused to report to spring training, deciding to stay at his home in North Bergen, New Jersey. There, working at a war plant, he maintained his 2-B draft status, deferred in support of war production. He kept in shape pitching semipro ball in Stamford, Connecticut, on the weekends and offdays.13 Late in July, the Brooklyn Dodgers, mired near last place, picked Fuchs up on waivers. While his being plucked off a semipro team might have seemed irregular, it was not without precedent. The Browns had signed Sig Jakucki, one of their better pitchers in 1944, off a semipro team in Texas.14 General manager Branch Rickey, who had come to Brooklyn from the Cardinals in 1942, was having a hard time maintaining a roster as the Dodgers were particularly hard hit by the draft. During the war years they lost top-notch players like Hugh Casey, Pee Wee Reese, Pete Reiser, and Billy Herman. Signing Fuchs seemed an act born out of desperation.

During a three-week period Fuchs pitched in eight games, proving ineffective as a reliever with a 1-0 record and a 5.74 ERA. His last major-league appearance came on August 5 against the Boston Braves. Fuchs lasted only one-third of an inning and allowed four runs. Shortly afterward he was waived to Montreal of the International League, where he went4-3 over the remainder of the season.

Fuchs finished his career in the majors with a 6-10 record, a 4.89 ERA, five complete games, and two shutouts. Save for appearing in 10 games as a hitter with the Nyack Rocklands of the Class D North Atlantic League in 1948, Fuchs’ professional career was over. His brief appearance with Nyack proved something of a closing flourish. Not an impressive hitter while in the majors, managing just a lowly .070 average, Fuchs posted a gaudy .563 average in 16 at-bats with one home run for Nyack. He was a switch-hitter, listed at 5-feet-8 and 168 pounds.

After his career ended, Fuchs became supervisor for Red Star Trucking, a local drayage concern. He subsequently left the company and opened a tavern. Fuchs died on June 10, 1969; his death certificate listed malignant hypertension as the cause of death. Fuchs was buried at George Washington Memorial Park in Paramus, New Jersey.15

Six months later, in December 1969, Fuchs’ wife, Gertrude, responded to a request from Cliff Kachline at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Kachline had written to Fuchs months earlier requesting that he fill out a player questionnaire. Mrs. Fuchs apologized for a tardy response, explaining that her husband had died. Writing that Fuchs had a “very special feeling for baseball,” she filled out the form Kachline sent, hoping it would be used to “complete his record.” 16

Kachline’s painstaking efforts illustrated early attempts to track down ballplayers, even those, like Fuchs, whose careers were brief and undistinguished. Kachline’s actions foreshadowed a more formal endeavor to trace the history of the game. Less than two years after receiving Mrs. Fuchs’ reply, he followed up on a suggestion of Bob Davids that likeminded baseball historians gather to create a “formal group” for research of baseball history and statistics by inviting them to meet at the Hall of Fame. There on August 10, 1971, the gathered participants created SABR. Thanks to individuals like Kachline and others who hunted down players like Fuchs through questionnaires and correspondence, that initial group was well on its way toward “establishing an accurate historical account of baseball through the years.”17

Several years after Fuchs died, another Fuchs graced major-league box scores. Charlie’s older brother, Lester, who had played briefly in the minors, had umpired for years in the New Jersey area. At the age of 66 he debuted as an umpire in the major leagues for one game between the New York Yankees and Oakland Athletics on August 25, 1978, working third base.18 The following year major-league umpires went on strike the first month of the season for better pay and working conditions. They were replaced by local amateur and retired umpires. During the first week of the season, Fuchs was called on to umpire two games between the Milwaukee Brewers and Yankees at Yankee Stadium.19 It is quite probable that as Fuchs stood down the third-base line, few if any in attendance knew he was the brother of a man who had pitched in the majors during World War II.

Notes

1 While several sources including Baseball Reference and Retrosheet refer to Fuchs as “Charlie,” a questionnaire filled out by his wife for the Hall of Fame, a cover letter written by her to Cliff Kachline, and several newspaper articles in his file at the Hall of Fame all refer to him as Charley.

2 In 1925 the adjoining towns of Union Hill and West Hoboken merged to form the city of Union City. See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union_City,_New_Jersey.

3 Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org both list Fuchs’ year of birth as 1913. His American League questionnaire lists his birth date as 1917; his wife filled out a posthumous questionnaire showing his birth date as 1913. Source: Fuchs’ file at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Inasmuch as his wife listed their date of marriage as February 18, 1931, it’s unlikely Fuchs was born in 1917.

4 Fuchs’ American League questionnaire in his player file at the Hall of Fame.

5 Ancestry.com

6 Undated, untitled article in Fuchs’ player file at the Hall of Fame.

7 Baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=fuchs-001cha.

8 “Fuchs, Rowe Touched for 16 Safeties,” Washington Post, April 4, 1942, 17.

9 “Phils Get Pitcher Fuchs,” New York Times, March 13, 1943, S3.

10 “Major League Flashes,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1943, 6. Notes on Fuchs in the article mention his having two children – the 1940 Census lists four: Bernice, Vaughn, Barbara, and Carol.

11 “Mack Dreams of a Wakefield to Wake Up A’s,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1943, 5.

12 “Browns Buy Pitcher Fuchs,” New York Times, July 20, 1943, 23.

13 “Major League Flashes,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1944, 14.

14 William B. Mead, Even the Browns, The Zany True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties, (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1978), 116-117.

15 Death certificate, questionnaire from Fuchs’ player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

16 Fuchs, Hall of Fame player file.

17 This is a portion of the Society for American Baseball Research’s mission statement.

18 Baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=fuchs-001les. Lester Fuchs is listed as a minor-league player at Baseball-Reference without any statistical data.

19 Retrosheet.org/boxesetc/F/Pfuchl901.htm.

Full Name

Charles Thomas Fuchs

Born

November 18, 1913 at Union City, NJ (USA)

Died

June 10, 1969 at Weehawken, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.