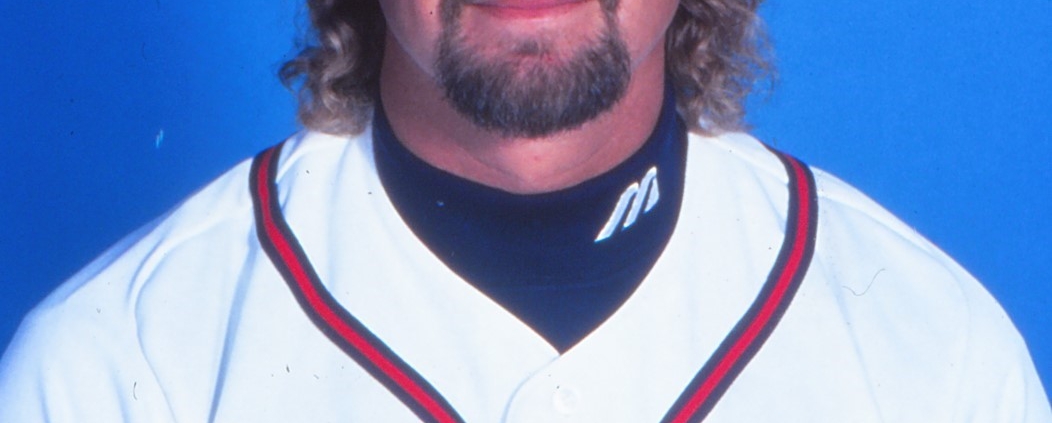

Charlie O’Brien

A baseball writer once compared Charlie O’Brien to Barry Bonds. Using the game of Monopoly to describe the range of players in fantasy baseball, he wrote, “Barry Bonds is Boardwalk. He costs the most money. Charlie O’Brien is like Mediterranean. He goes the cheapest.”1 Okay, it wasn’t the most flattering comparison, but Charlie would take it. He didn’t really care what people said about him. He had a 15-year career and a World Series ring, all because he was one of the best play-callers in the game.

A baseball writer once compared Charlie O’Brien to Barry Bonds. Using the game of Monopoly to describe the range of players in fantasy baseball, he wrote, “Barry Bonds is Boardwalk. He costs the most money. Charlie O’Brien is like Mediterranean. He goes the cheapest.”1 Okay, it wasn’t the most flattering comparison, but Charlie would take it. He didn’t really care what people said about him. He had a 15-year career and a World Series ring, all because he was one of the best play-callers in the game.

Charles Hugh O’Brien was born on May 1, 1960, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His father, Charles Raymond O’Brien, was a partner in the family business, O’Brien Meat Company. His mother, Ann Kelley, was a homemaker in charge of their nine children. The family had a sporting background, with Charles having played football and baseball at the University of Tulsa. During his major-league career Charlie wore several uniform numbers, but mostly his preference was for the number 22, to match his father’s football number.

Charlie played baseball and hockey from a young age, and first put on catcher’s gear at age 5. He admired Reds catcher Johnny Bench as a youth. “I tried to catch like Bench,” he said. “I tried to hit like him, too. But that went away pretty quick.”2

O’Brien’s younger brother John played a few seasons in the Cardinals system in the early 1990s, not advancing past Class-A ball, then spent several years in independent leagues.

O’Brien starred at Bishop Kelley High School in Tulsa, winning two state championships. He was picked in the 14th round of the 1978 amateur draft by Texas, but chose to go to college. He attended Wichita State in Kansas, where he played alongside seven future major leaguers on a highly successful team. Among his teammates was pitcher Erik Sonberg, who achieved lasting fame by being drafted one spot ahead of Roger Clemens in the 1983 draft. Sonberg reached Triple A but never pitched in the majors. He later became a member of the O’Brien family when he married Charlie’s sister.

In 1982, under legendary college coach Gene Stephenson, Wichita State set an NCAA record that still stood in 2020 by winning 73 games, but lost to Miami in the College World Series championship game. O’Brien paired with Russ Morman and Phil Stephenson to become the first trio of NCAA teammates to each have 100 RBIs in a season. O’Brien was named an All-American that year, and Gene Stephenson was impressed. “Charlie is the best catcher in the college ranks right now, I believe,” he said.3

O’Brien had been drafted as a junior by Seattle in 1981 (21st round), but signed with Oakland after going in the fifth round of the 1982 draft. He received a bonus reported as $12,500.4

O’Brien split his first minor-league season at two Single-A stops, and found himself up against Oakland’s other top catching prospect, Mickey Tettleton. The competition between them continued for years, but in the early days O’Brien proved better and was promoted to Double A for 1983. He had an excellent season there, hitting .291 with 14 home runs, but missed the last month with a back injury. He was promoted to Triple-A Tacoma in 1984, but leg and back injuries once more curtailed his season.

With a traffic jam at catcher in the A’s system, O’Brien was sent to Double-A Huntsville at the beginning of 1985. Teammate Luis Polonia later claimed that he and O’Brien got into a fight one day, with Polonia saying, “I broke the bus window with his head.”5 Polonia went on to say that O’Brien promised payback, which he got during an on-field fight in 1989. O’Brien denied they had ever fought.

O’Brien was surprisingly called up to the parent club in late May as rumors swirled that Oakland was going to trade starting catcher Mike Heath. His major-league debut on June 2 was inauspicious, as he caught the eighth inning of a 10-1 loss in Baltimore. He spent his time on the bench behind Heath (who was not traded) and Tettleton. O’Brien spent a month with the A’s but got in just one more appearance — also as a one-inning defensive replacement — before being optioned to Class-A Modesto. The reason for the three-level drop was that the higher-level teams already had starting catchers.6 After a couple of weeks in Modesto, though, he was promoted to Tacoma.

O’Brien returned to Oakland in mid-August when Tettleton went on the disabled list. This time he got into four games, with one start, before being sent back down on Tettleton’s return. He was called back up when rosters expanded. He got into several games defensively, and made his second start of the season in the last game of the season, where he also got his first career RBI.

The A’s surprised O’Brien by trading him to Milwaukee at the end of spring training in 1986. The Brewers sent him to Triple A, which was discouraging, but he ran into Steve Carlton as he was leaving. “‘You’ll be back,’ he said. ‘You’re too good a catcher. I like the way you catch.’ Hearing that from a Hall of Fame guy like Carlton was great. He didn’t have to take the time to say that. Gives you confidence.”7

After a few weeks at Vancouver, where he got little playing time behind B.J. Surhoff, O’Brien was sent down to Double-A El Paso. He reignited his status as a top prospect by hitting .324 with 15 home runs. A chipped thumb from a foul tip slowed him at the start of 1987, and he was sent to Triple-A Denver. He spent the year there, except for a few weeks in May when he was called up to the Brewers because Surhoff’s father died and backup catcher Bill Schroeder had a sore elbow. O’Brien got into 10 games, all of them starts, and while he hit just .200, he impressed by throwing out 9 of 14 attempted basestealers. Oddly enough, on a team that finished the season 91-71, and was 20-4 when he was called up, Milwaukee lost all 10 games that O’Brien played in.

He started 1988 back in Denver, but was called up again in mid-June. O’Brien played well enough that he mostly took over the backup catcher role from Schroeder, playing in 40 games in the second half of the season. Despite a .220 batting average, he did manage to hit his first career home run in July, off Kansas City’s Floyd Bannister.

The 1989 season began with Surhoff as the primary catcher, but as the year went by and Surhoff struggled at the plate, O’Brien got more playing time based on his defense. By the end of the season, pitcher Chris Bosio requested that O’Brien be his personal catcher, the first of a number of pitchers who made that request in O’Brien’s career.

Around this time O’Brien began standing out by wearing brightly-colored catcher’s gear. In Milwaukee he wore a bright yellow chest protector, and with the Mets he switched to orange. “This way, if my mom and dad are watching the highlights on TV and there’s a play at the plate, they’ll be able to tell right away if I’m catching,” he said.8

O’Brien struggled with the bat during 1990, hitting just .186 with the Brewers. His defense was still strong, but the Mets traded for him just before the deadline, needing a catcher for the pennant run. With starter Mackey Sasser hurt, O’Brien was called upon to start 25 of the last 33 games for the Mets, including twice catching both ends of a doubleheader. He could not help, though, as the Mets slowly fell away by the end of the season.

At the start of 1991 the Mets named O’Brien as the starter, but poor hitting — he was as low as .146 in July — meant that he slipped down the pecking order. He had spent the winter working on his hitting, coming off a career-low .178 between the Brewers and Mets, but nothing seemed to help.

In fact, to get more playing time in the second half, O’Brien relied on an old trick — becoming someone’s personal catcher. This time it was Dwight Gooden. Caught by all three catchers, Gooden had struggled to a 4.39 ERA through the end of June, but O’Brien caught him exclusively from then on and his ERA fell to 2.28. “There’s something about it. I know what he wants to do and that makes him feel comfortable,” O’Brien said.9 Perhaps it was something else, though, an ability to not back down from the star pitcher. “Charlie wouldn’t be as nice as other catchers when he approached you. … He was very direct. He would get right in your face, basically nose-to-nose, if he felt like you weren’t giving one hundred percent out there or that you weren’t giving it your all every pitch,” Gooden said.10

The bad news for O’Brien was the arrival of a young catcher at the end of the season. Todd Hundley had shown good catching skills in the minors, and just as importantly a good bat. This gave him a leg up over O’Brien. Hundley came up in September 1991 and caught almost every day. O’Brien did catch the last game of the season, when his pitcher, David Cone, tied the National League record with 19 strikeouts.

The 1992 season opened with manager Jeff Torborg calling Hundley his starter. O’Brien remained as Gooden’s personal catcher, which accounted for almost half of the games he caught in 1992. Late in September, O’Brien broke his wrist when a foul ball hit it, ending his season with a week left. He took the opportunity to have surgery on both knees, cleaning up some ongoing issues.

O’Brien went into 1993 once more as backup to Hundley, but switched away from being Gooden’s personal catcher to sharing the workload more evenly. He also hit .255, his highest average for a full season to that point, which was well-timed as he entered free agency for the first time.

O’Brien later said that he didn’t like playing for the Mets. His feeling was that the players had too much fun away from the team to care about winning. They didn’t have a tough manager to take care of that, and there was no player who was enough of a leader that he would be willing to call out others.

O’Brien signed a two-year, $1.1 million deal with the Atlanta Braves. The goal was for him to be the veteran backup behind rookie phenom Javy Lopez, and help Lopez improve on the defensive and game-calling side. Being the backup didn’t bother him. “It’s not a label I cherish, but I’ve made a living doing it,” he said.11 Braves manager Bobby Cox said that O’Brien would get playing time. “To me he’s the best catch and throw guy in the league.”12

O’Brien ended up catching more than a third of the games in the strike-shortened season. He got more playing time each month as Lopez did not perform as expected. O’Brien also became the personal catcher for John Smoltz, catching every one of his games as the Braves preferred the veteran catcher for the sometimes-wild pitcher. He made headlines in May for a different reason: After Smoltz hit the Mets’ John Cangelosi to start a brawl, O’Brien ended up on the cover of Sports Illustrated, shown punching Cangelosi to the ground. “Hopefully, my kids won’t see it,” he said.13 He received a $1,000 fine for the fight.

The following season Smoltz switched to being caught exclusively by Lopez, and O’Brien caught almost all of Greg Maddux’s starts. The pitchers talked about the differences between the two catchers, but Lopez chafed at not being able to get into a groove by catching every day. Maddux had confidence in O’Brien. “We work well together. I very seldom shake him off. I watch all the catchers on TV closely and to me, Charlie is easily the best in baseball,” Maddux said.14

It worked, as the Braves lapped the field in their division, then cruised through the playoffs to win the 1995 World Series. O’Brien started every one of Maddux’s starts in the playoffs, but was regularly replaced by Lopez in the middle innings when the Braves were looking for a bigger bat. His one offensive highlight was a three-run home run off Cincinnati’s David Wells to give the Braves a lead they did not relinquish in Game Three of the NLCS. “Close your eyes and swing,” he said. “Sometimes it works.”15

The Braves let O’Brien go to free agency, and he left Atlanta as a world champion. Still, he was irked at the way they treated him, even down to getting his World Series ring. “I got my ring from a UPS deliveryman. Out of sight, out of mind.”16

O’Brien signed a two-year deal with Toronto for $1.125 million. For the first time he was the starting catcher, and he set career highs in almost all counting stats, including 13 home runs in his 109 games. The home runs were a surprise for O’Brien. “I never go up expecting to hit them out. I’m just a hacker. If it goes, it goes. I don’t think about it,” he said.17

In 1997 Toronto splashed $6.5 million on free agent catcher Benito Santiago. Santiago’s 1997 ended up worse than O’Brien’s 1996 in most categories, and by midseason O’Brien was getting more playing time. When Roger Clemens chose O’Brien as his personal catcher, Santiago was so irritated that he threatened to demand a trade. He instead reasserted himself and hit 100 points higher in the second half of the season, pushing O’Brien back to the backup spot. A rare batting highlight for O’Brien came on May 14 in Detroit, when his career-high six-RBI day was led by his first grand slam.

Around this time O’Brien became frustrated with his mask, and the headaches that came from being hit by foul tips. Watching hockey, he realized that goalies were hit with much harder force by a puck but were much better protected by their helmets. He began working with a Canadian company to adapt a hockey-style mask for baseball. The helmet he came up with provided better protection and visibility.18 It took months for Major League Baseball to approve it for game use, which annoyed O’Brien. “These things are safe enough for hockey goalies, so why is it taking so long?”19 He finally used his mask in a game for the first time against the Yankees. Yankees catcher Jim Leyritz immediately ordered one for himself.

The mask quickly spread around the league, with a number of players wearing it the next season. Within a few years the helmet-style mask became widely used at all levels of the game.

O’Brien became a free agent at the end of 1997, and had a few parting shots as he left Toronto. In particular he ripped into Santiago, unhappy at the feud that had developed between them. He said that Santiago was overpaid for the production he had brought. “I don’t know what I did wrong there, but if they want to pay a guy (Santiago) $3 million who hits just 13 home runs, well, they got him.”20

O’Brien signed another two-year deal, this time with the White Sox for $1.4 million. They signed O’Brien and Chad Kreuter on the same day, apparently figuring to let the two veteran catchers battle to see which would be the starter. They split time until O’Brien suffered a chip fracture of his right thumb in July and went on the disabled list for the first time in his career. While on the DL, he was sent to Anaheim for two minor-league pitchers at the trade deadline.

Anaheim was leading the AL West and looking to pick up the veteran catcher for the stretch. When O’Brien arrived, his thumb was examined by doctors, who determined it was not healing and he would miss another month. The Angels activated him in early September, but he played in just five games before being hit by a pitch and breaking another finger, which ended his season. Oddly enough, the Angels then acquired Kreuter to finish out the season while O’Brien went back on the DL. Neither of them provided any help as the Angels fell out of contention.

O’Brien didn’t fare any better in 1999, when a torn ligament in his foot put him on the DL in early June. He returned after six weeks out, but just a week later was released, having hit .097 for the season.

O’Brien wasn’t quite ready to give it up. He signed a minor-league deal with Montreal for the 2000 season. After another foot injury cost him most of spring training and the first month of the season, he was sent to Double-A Harrisburg to start the season. He was called up to the Expos after a couple of weeks. He spent a month with Montreal before being released, with the final straw apparently coming when he allowed five stolen bases in a game against the Yankees. Montreal offered him a job as the bullpen catcher, but he decided it was time to go home.

O’Brien had married Traci Rodriguez, and they had four children — two girls and two boys. While they grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the family had regularly spent summers wherever their father was playing, and had recollections of interactions with players on a personal level.

O’Brien bought a ranch in northeast Oklahoma, and named it the Catch-22 Ranch, for his uniform number. O’Brien was an avid hunter, and during his career he went hunting with several other players, among them Chipper Jones and Will Clark. He appeared on hunting shows on ESPN and other channels. As of 2020, on his ranch he hosted tour groups on hunting trips. He created a company, Charlie O’ Products, which creates and sells items for hunters. He has also hosted a show for hunters, Deer Thugs, which aired on cable TV.

O’Brien’s two boys, Chris and Cameron, played college and then minor-league baseball. Charlie coached their high-school teams, but stopped coaching when they went to college. He and Traci regularly traveled to see their sons play in college and the minor leagues, although he wasn’t necessarily a good watcher. “The game moves so much quicker on the field than it does from the stands. After seeing it from the angle that I saw it from for all those years, it’s kind of boring to be up in the stands.”21

Chris followed his father’s footsteps to Wichita State, and was taken by the Dodgers in the 18th round of the 2011 draft. Playing mostly catcher, he reached Triple A in the Orioles system before retiring after the 2017 season. Cameron attended several colleges, was undrafted, and spent two seasons in Low-A ball for Toronto. Both brothers received 50-game suspensions for taking amphetamines, which effectively ended their playing careers.

O’Brien gained notoriety in 2012 when he appeared as a defense witness in the perjury trial of his former teammate, Roger Clemens. In his testimony, he was emphatic in his belief that Clemens never took steroids, although he struggled to remember things about other teammates. However his testimony appeared, it was not too damaging; Clemens was acquitted.

O’Brien wrote a book about his career, called The Cy Young Catcher. In it he claimed to have caught a record 13 pitchers who won the Cy Young Award, and detailed each of their careers and his interactions with them. Although the claim is technically true, O’Brien caught just four of them during their Cy Young-winning years (Maddux twice, Pat Hentgen, and Clemens). Of the rest, some were very late in their careers (he caught Pete Vuckovich only in spring training) and others very early. (Chris Carpenter won his Cy Young several years after O’Brien had retired.)

Many pitchers had good things to say about O’Brien’s ability as a defensive catcher and the way he called a game. If selecting him as a personal catcher wasn’t enough, to a man they praised how he called a game, and how he was able to get in sync with his pitcher. “From the first time I met him, he seemed like a guy who was born to be a catcher,” said Don Sutton. “He received the ball with almost pillow-like hands. He knew how to throw. But I think he had that innate sense of what a pitcher was trying to do, and how can we use that to get the hitter.”22

Last revised: February 27, 2021

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on Charlie O’Brien’s book, The Cy Young Catcher, and on baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Stephen Nover, “Leagues Can Keep Games Interesting Even for Most Jaded,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, December 12, 1993: 2E.

2 Marty Noble, “O’Brien Hit One for All Journeymen,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, October 15, 1995: 10B.

3 “Oelkers Hurls WSU to 11th Win in Row,” Wichita (Kansas) Eagle, March 22, 1982: 5B.

4 Randy Brown, “Unsuccessful in Series Bid, WSU Looks at 1983,” Wichita (Kansas) Eagle, June 14, 1982: 1B.

5 Claire Smith, “Yankees,” Stamford (Connecticut) Advocate, September 22, 1989: B5.

6 “The A’s,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 2, 1985: 46.

7 Charlie O’Brien and Doug Wedge, The Cy Young Catcher (College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 2015), 13.

8 “Seventh-Inning Stretch,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 5, 1990: 11C.

9 Nat Gottlieb, “O’Brien Delighted with Doctor’s Duty,” Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, July 23, 1991: B2.

10 O’Brien, The Cy Young Catcher, 45.

11 Bill Zack, “O’Brien Relishes Tutor’s Role as Backup to Braves’ Lopez,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, March 21, 1994: 1B.

12 Tom Saladino, “O’Brien Insurance for Braves,” Brunswick (Georgia) News, March 19, 1994: 3B.

13 Bill Zack, “Braves Notes,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, May 20, 1994: 2C.

14 “Sizzling Maddux Rolls On,” Columbia (South Carolina) State, September 1, 1995: C4.

15 Marty Noble, “O’Brien Hit One for All Journeymen,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, October 15, 1995: 10B.

16 O’Brien, The Cy Young Catcher, 179.

17 “Extra Bases,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 3, 1996: C4.

18 Cliff Gromer, “Blue Plate Special,” Popular Mechanics, April 1997: 59.

19 Simon Gonzalez, “Baseball Report,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 18, 1996: C8.

20 “Catcher O’Brien Rips Santiago, Blue Jays,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, November 24, 1997: 14C.

21 O’Brien, The Cy Young Catcher, 2.

22 O’Brien, The Cy Young Catcher, 177.

Full Name

Charles Hugh O'Brien

Born

May 1, 1960 at Tulsa, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.