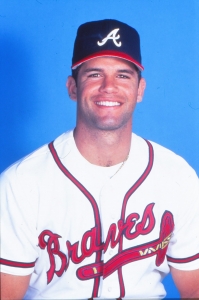

Javy Lopez

Javier Torres “Javy” Lopez was born on November 5, 1970, in the city of Ponce, Puerto Rico. Lopez was a right-handed-hitting catcher who played for the Atlanta Braves, Baltimore Orioles, and Boston Red Sox over his 15-year major-league career, though he is primarily known for his time with the Braves. Lopez was a three-time All-Star and one-time Silver Slugger recipient, and in 1995 was a World Series champion, all with the Atlanta Braves. Lopez is listed at 6-feet-3 and 185 pounds,1 but by his own admission, his weight climbed to at least 248 pounds during his career.2

Javier Torres “Javy” Lopez was born on November 5, 1970, in the city of Ponce, Puerto Rico. Lopez was a right-handed-hitting catcher who played for the Atlanta Braves, Baltimore Orioles, and Boston Red Sox over his 15-year major-league career, though he is primarily known for his time with the Braves. Lopez was a three-time All-Star and one-time Silver Slugger recipient, and in 1995 was a World Series champion, all with the Atlanta Braves. Lopez is listed at 6-feet-3 and 185 pounds,1 but by his own admission, his weight climbed to at least 248 pounds during his career.2

Javy was the second youngest of five children (two boys, Juan Eduardo and Javy, and three girls, Sandra, Betsy, and Elaine) in his household, and learned from an early age the value of hard work from his parents and his lower-middle-class upbringing. Lopez’s mother, Evelia Torres, held many jobs ranging from bank teller to teacher, but she eventually left the work force to better provide supervision and care for her children. This left Jacinto Lopez, Javy’s father, an auto-parts dealer, former employee of a credit union, and occasional car salesman, as the primary source of income for the family. The modest, four-bedroom house in which Javy grew up lies in close proximity to the other homes on his block, and lent itself perfectly to providing close familial and neighborly ties. The values growing up in this modest family created a bond that Lopez has reflected upon.3

Javy’s first swings came when he took an old bat and a bucket of rocks to the roof of his house and hit the rocks into the vacant lot across the street. Jacinto Lopez recalled the stamina Javy displayed while doing this: “I’d be on the couch and he would be up there swinging at stones. I would say to myself, gosh, this kid never gets tired.”4 At 7 years old Lopez began playing baseball at a neighborhood church on a concrete field with a rubber ball.5 Whenever a bat or tape to make a ball could not be found, Javy and his friends improvised with broomsticks and soda-bottle caps. Any materials that could be feasibly used as a bat or ball were used.6

Lopez did not know the idiosyncrasies of baseball but he did enjoy playing the game and began to develop a knack for it as well. His father took him to a recreational league when he saw his son’s potential. Once the duo started playing catch, coaches took notice of Javy’s potential and put him on a team. Javy demonstrated a strong arm, but lacked the touch or control to pitch, the agility to play shortstop, or the swiftness to patrol the outfield. But he hit well, so the coaches kept plugging him in at different positions until one worked for him. Lopez benefited from baseball being a year-round sport in Puerto Rico. As soon as one season ended, Lopez went to another team to play. The repetition and extra coaching were invaluable in developing his defensive skills, and it was by the time he made his third team that Lopez began to find his way and started to feel comfortable on the diamond.7 Baseball even taught Lopez an early life lesson. His uncle bought him his first baseball glove and Javy left it on the patio one day. Someone stole the glove and Javy learned how to properly keep track of his belongings.8

By age 13 Lopez still did not have a true position, but one of his managers, Johnny Rodriquez, tried him at catcher. Lopez was not great at blocking balls or catching bad pitches, but his arm was strong enough to compensate for his rawness behind the plate; he threw out a plethora of runners on his first day as a catcher, and thus his position was found.

Lopez’s hard work was rewarded when he was signed as an amateur free agent by the Atlanta Braves in 1987.9 He turned down offers from the New York Yankees, San Diego Padres, and Montreal Expos to sign with the Braves, who offered $45,000 while the Padres and Expos were offering $75,000. Jacinto Lopez explained: “TBS used to be the only station that showed games here, so we were Braves fans.”10 After Lopez signed with the Braves, even more teams began to pursue him, but he honored his contract. Lopez said, “You know what? Forget it! I’m going to be in Atlanta, on TBS!”11

For what it is worth, Lopez might not have been the best athlete, or even the best baseball player in his family, at least for a time. His sister Elaine was at one point regarded as one of the best beach volleyball players in Puerto Rico, if not the best. Elaine also was married to former American League MVP Juan Gonzalez for a time, causing a fun debate on which member of the extended Lopez family was the best baseball player.12

Lopez started with the Braves’ team in the Gulf Coast League (rookie) as a 17-year-old in 1988. Each subsequent year he advanced a level, and in September 1992 he made the jump from Double-A Greenville (Southern League) to the Braves. No stop was without trials and tribulations, but Lopez continued to show promise. For example, Lopez had 31 passed balls playing for Burlington, Iowa (Midwest League). Lopez blamed his fear of the ball, the cold weather, and the pitchers lacking the ability to properly grip the ball in that climate.13

During his rise through the minors, Lopez paused in 1991, while playing for Durham (Carolina League) to marry his childhood sweetheart, Analy Hernandez.14

Called up from Greenville, Lopez made his major-league debut on September 18, 1992, at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, hitting a pinch-hit double off Houston’s Rob Murphy in his first at-bat. He was 6-for-16 in a nine-game audition, then opened the 1993 season playing for the Triple-A Richmond Braves. Called up in August, he played in only eight games but hit his first major-league home run on August 21 at Wrigley Field against Chicago Cubs reliever Shawn Boskie.

By Opening Day of the 1994 season, the 23-year-old Lopez had become the Braves’ starting catcher, replacing Damon Berryhill. He performed well enough to earn a top-10 spot in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting, and learned quite a bit about handling a major-league pitching staff — one with three future Hall of Famers, Greg Maddux,John Smoltz, and Tom Glavine.

It was, however, a starter from the back end of the rotation, Kent Mercker, who provided Lopez his most memorable game in 1994. On April 8 the Braves were visiting the Los Angeles Dodgers for their fifth game of the season. Kent Mercker was on the mound for the Braves and Lopez was behind the plate. Despite some first-inning trouble (two walks), Lopez was able to guide Mercker out of the inning unscathed. Mercker finished the game with 10 strikeouts, four walks, and zero hits allowed. As of 2019 the game was the last no-hitter pitched by a member of the Braves.

After the strike-shortened season of 1994, and the late start to the 1995 season as the strike wound down, Lopez solidified his spot in the starting lineup for the perennial playoff contender Braves. He improved in every major statistical category, and by the end of the season there was no doubt who the backstop of the future was for the Braves. In the postseason Lopez helped the Braves slug their way past the Colorado Rockies and Cincinnati Reds, and provided one of the greatest plays of the World Series, against the Cleveland Indians.

In the bottom of the sixth inning Lopez hit a line-drive, two-run home run off Dennis Martinez that gave the Braves a 4-2 lead, which they did not relinquish.

In the top of the eighth, the Indians’ Manny Ramirez was on first and slugger Jim Thome was at bat. Lopez had observed Ramirez’s penchant for a large lead off the bag and decided to take a chance at stealing an out. Lopez recalled, “McGriff looked at me, and I signaled to him by touching the ground and picking up the dirt. He signaled back by tugging on his pants.’’15 On a 2-and-2 count, Alejandro Peña threw a pitch up and in, which Thome did not offer at. Lopez flung the ball to Fred McGriff at first, catching Ramirez by surprise for the second out of the inning. Thome walked on the next pitch, and without Lopez’s pickoff throw, the eighth inning might have unfolded differently. “It was the best feeling in the world,” Lopez recalled.16

The Braves won the World Series in six games. Just nine days after Lopez jumped into Mark Wohlers’ arms as a World Series champion,17 Javy and Analy welcomed the couple’s first son, Javier Alexander, to the world. It was certainly about as good a two-week stretch anyone can hope to have.18

The 1996 regular season was a respectable one for Lopez. He eclipsed the 20-home-run mark for the first time. But Lopez again saved his best performances for the postseason. In the NLCS he helped guide the Braves back from a three-games-to-one deficit against the St. Louis Cardinals by going 13-for-24 with two home runs, five doubles, and three walks. Lopez did not maintain this torrid pace in the World Series, which the Braves lost in six games after taking a 2-games-to-none lead over the New York Yankees. Lopez was 4-for-25.

Lopez was selected for the National League All-Star team in 1997 and 1998. He showed solid power, called a respectable game behind the plate. Lopez finished the 1998 season with 34 home runs, two shy of Joe Torre’s franchise record of 36 home runs by a catcher.19 In both seasons the Braves were defeated in the NLCS.

In 1999 Lopez suffered the first major setback in his career. Lopez was having another strong year statistically, but in late July Lopez suffered a torn ACL, and his season was finished.20 Also that year Lopez’s mother died after having a stroke, and his father had quadruple bypass surgery. As Jacinto Lopez recovered in the Lopez family home, Javy decided to buy the house next door and moved in Jacinto’s twin sister, Lourdes, where she helped take care of Jacinto and kept him company. Lopez also decided to provide everything his father needed financially so he did not have to return to his high-stress job as a newspaper distributor. Professionally, Lopez watched the Braves make another World Series run, but were swept by the Yankees. Lopez wondered how much he could have helped the Braves in the Series. Lopez was also coming to terms with his failing marriage, a brother addicted to drugs, and his sister Elaine’s pending divorce from Juan Gonzalez. He acknowledged that the combination of all of these issues left Lopez in quite a negative state of mind.21During this tumultuous time, Lopez’s second son, Kelvin Gabriel, was born.22

Lopez returned with a solid 2000 season, but the decline in his game was starting to become evident. His batting and power numbers slipped in 2001 and 2002, and rumors that the Braves would move on from Lopez became more and more audible. A team built around a pitching staff cannot afford to have a liability at catcher, especially a catcher paid as an All-Star-caliber player but who no longer performed as one, and this was on a team with growing budgetary concerns. One of the issues that plagued Lopez throughout the 2002 season was a contentious divorce and the fear that Lopez might become estranged from his two sons. The mental toll of the divorce and custody battle was tremendous, and were probably a strong factor in some of Lopez’s shortcomings on the field.23

Then … The 2003 season was undoubtedly Lopez’s best, statistically speaking. He was at a crucial juncture in his career. Lopez was 32 years old and played a position in which players do not typically age gracefully. He had come off a dismal 2002 season, and faced the realization that the Braves had recently acquired their supposed catcher of the future in Johnny Estrada. Long gone were the All-Star campaigns of 1997 and 1998, and the postseason heroics of the mid-1990s. The reality was that Lopez was a hit-first catcher with some pop who no longer could hit — or at least that was what the baseball world believed. Lopez heard the critics, and in many regards he agreed with their assessment of the state of his game.

Lopez entered the 2003 season with a new mental approach and a revamped conditioning program. No longer the flabby 248-pound catcher eating everything in sight, he was a lean 210-pounder who lifted weights multiple times per week instead of once or twice a month, the regimen he followed in previous seasons.24 Whether these improvements were the result of hard work and determination or chemical enhancements, as was the theme of baseball of the period, could be debated for years to come. Lopez even created some doubt on his new physique with interviews in which he was a little too coy about the subject. In an interview in 2010 he reflected upon 2003: “Well, everybody seen players getting big, hitting the ball harder, home runs and stuff. All of a sudden — boom — they got the big contract and everybody’s like, ‘You know what, did that, it worked for him, why not do it?’… I mean, how can I explain this? It’s like if you’re going to race cars, if you’re going to race a car and some people are using nitro in the fuel [Lopez laughed], and you see them winning all the time, and you’re using regular gas — you know what? If they’re using nitro and they’ve been winning, well, I’d be stupid enough not to use nitro, too.”25

But the fact remains that Lopez showed tremendous results from his lifestyle changes, regardless of how they were obtained, and slugged his way to an incredible 2003 season. Even the noticeable focus on his diet and conditioning did not create immediate benefits. Lopez had to stop fighting his psyche in the batter’s box — taking every out as an indictment of his abilities —and had to have faith in his natural abilities. Also, Lopez opened his stance a bit, and began to reap the benefits. He made consistent and hard contact.26 His new approach, conveniently in a contract season, created Lopez’s finest season in the big leagues with career highs in home runs (43), RBIs (109), batting average (.328), on-base percentage (.378), and slugging percentage (.687). Lopez established the major-league record for home runs by a catcher, 42 (one of his home runs came via a pinch-hit against the Mets in July). He played in his third and final All-Star Game (he was the starting catcher for the National League) and was poised to cash in on his success in the coming free-agency period. But all of this success still did not mean that Lopez would be catching one of the best pitchers of his generation, Greg Maddux.

One of the most discussed aspects of Lopez’s career was his professional relationship with Maddux. Attempting to explain why the most talented catcher on the roster was not catching Maddux, arguably the best pitcher in the league, article after article was published suggesting that, at least at some level, there was a rift between the two.

Both players downplayed the drama, but every time Maddux toed the rubber and Lopez was not behind the plate, there would be a comment or question about it. In fact, between September 8, 1998, and September 28, 2003, if Lopez caught a pitch from Maddux, it was because Lopez entered the game late as a pinch-hitter, and manager Bobby Cox did not want to remove his ace pitcher from the game just yet.27 Fueling the controversy was the fact that in 1994, when Maddux led the league with a 1.56 ERA, Lopez caught 22 of his 25 starts. So, on paper at least, it seemed as if the two players could coexist in the same game.

Eddie Perez was a longtime backup catcher with the Braves and personal favorite of Maddux; he also downplayed the rift. Perez said a player knowing when he would get to play or have a day off was important for staying mentally sharp throughout the grind of the long season, and Maddux was able to provide this for two players, Lopez and his backup, each season.28 Even in the playoffs, Bobby Cox adhered to his distaste for pairing Maddux and Lopez in the battery despite endless objections and questions from the media. It just seemed to be regarded as certain that Lopez was not going to be catching Maddux, regardless of the magnitude of the situation.29 After his career was over, Lopez did admit that it bothered him that he did not catch Maddux in some of the biggest situations for the Braves. He wondered if the Braves could have won even more if he had caught Maddux, and he wondered how much more gaudy his own 2003 season would have been with the added at-bats from catching Maddux on a consistent basis.30

After his dominant 2003, Lopez did test the free-agency waters and landed in Baltimore, which was attempting to revamp its offense. Lopez played in a career-high 150 games, and batted .316. It was easily his second best season in the majors. Despite his impressive stats, Lopez was on a losing team for the first time in his career and watched the postseason from home, but at least he was not watching alone.31 The move to Baltimore coincided with another major happening in his life. On June 23, 2004, he married his second wife, Gina.32

The 2004 season was Lopez’s high-water mark with the Orioles, and in August of 2006 he was jettisoned to the Boston Red Sox for a journeyman player, Adam Stern. He played in 18 uneventful games before being released in September. Lopez was re-entering the free-agency pool with much less luster than in his previous free-agency campaigns. Lopez signed with the Colorado Rockies but was released before the 2007 season began. He tried a comeback with the Braves in spring training in 2008, but decided to retire when it became evident that he just could not hit the ball the way he once did and he was reassigned to the minor-league camp.33

Lopez retired with a career batting average of .287, 260 home runs, a World Series ring, an NLCS MVP award, three All-Star team selections, one Silver Slugger Award, over $61 million in earnings, and an incredible pickoff throw in the 1995 World Series. He had played on 11 division winners, and had that magical 2003 season when he set the season record for home runs by a catcher.

Lopez founded Bones Bats, a company that made hardwood bats, so that he would still have some connection to baseball.34 He chose to use the word Bones instead of his name because he knew no player would buy a bat to use in the major leagues with another player’s name on it. Appealing to major-league players with the bat did not work, and most of the sales were to the amateur ranks and dealers. Bones Bats did not prosper as Lopez had hoped, but he felt strongly about his product and said he would continue to produce bats as long as he felt this way.35

Lopez occasionally traveled to Florida to help coach the Braves young players during spring training. He was inducted into the Atlanta Braves Hall of Fame during the 2015 season.36

Lopez and Gina settled in Suwanee, Georgia, in the Atlanta metropolitan area. They had two sons, Brody, born in 2014, and Gavin, born in 2010. He began to play in charity golf tournaments.37 Lopez also enrolled in Leadership Gwinnett to learn more about his community and its government, and to network with people outside of baseball.38 He also spent more time at his longtime hobby of remote-control airplane flying.39 Lopez also strove to make at least two trips a year to his native Puerto Rico, especially for New Year’s Eve, which was a time for rejoicing and celebration with his family and friends at his sister’s home.40

Last revised: February 11, 2020

Notes

1 Both baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org list Lopez at that height and weight.

2 Associated Press, “Javy Lopez: What a Difference a Year Makes,” Augusta Chronicle, June 28, 2003.

3 Javy Lopez and Gary Caruso, Behind the Plate: A Catcher’s View of the Braves Dynasty (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2012), 15-16.

4 “Braves: Javy Lopez Returns to His Roots. Puerto Rico Welcomes Native Son Home,” Savannah Morning News, April 15, 2003.

5 Lopez and Caruso, 20.

6 “Braves: Javy Lopez Returns to his Roots.”

7 Lopez and Caruso, 20-22.

8 “Braves: Javy Lopez Returns to his Roots.”

9 Lopez and Caruso, 22-29.

10 “Braves: Javy Lopez Returns to his Roots.”

11 Lopez and Caruso, 28.

12 I.J. Rosenberg, “Whatever Happened To: Ex-Brave Javy Lopez,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 1, 2015.

13 Lopez and Caruso, 32.

14 Lopez and Caruso, 109.

15 I.J. Rosenberg, “Javy Lopez Remembers Picking Off Manny Ramirez,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 1, 2015.

16 Gene Sapakoff, “Javy Lopez Recalls ‘Goofy’ Maddux, Respect for Former Braves Coach Cox,” Charleston (South Carolina) Post and Courier, January 28, 2014.

17 Lopez and Caruso, 111.

18 Sapakoff.

19 Mike Berardino, “Lopez Finally Grabbing Headlines,” South Florida Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), September 13, 1998.

20 “Braves Lose Lopez For Season,” https://cbsnews.com/news/braves-lose-lopez-for-season/, accessed February 1, 2017.

21 Lopez and Caruso, 103-104.

22 Lopez and Caruso, 111.

23 Roch Kubatko, “Clearing His Mind, Though Not His Plate,” Baltimore Sun, February 23, 2004.

24 Associated Press, “Javy Lopez: What a Difference a Year Makes,” Augusta Chronicle, June 28, 2003.

25Craig Calcaterra, “Javy Lopez on Steroids: ‘I’d be Stupid Not to Use Nitro Too,” Hardball Talk, http://mlb.nbcsports.com/2010/02/05/javy-lopez-on-steroids-i/, accessed December 14, 2016.

26 Associated Press, “Javy Lopez: What a Difference a Year Makes.”

27 Rafael Hermoso, “Baseball: If Maddux Is Pitching, Lopez Isn’t Catching,” New York Times, October 5, 2002.

28 Mark Bowman, “For Perez, a Front-Row Squat at Maddux’s Greatness,” MLB.com, https://m.mlb.com/news/article/66355592/former-braves-catcher-eddie-perez-reflects-on-greg-madduxs-greatness/, accessed January 15, 2017.

29 Rafael Hermoso, “Baseball: If Maddux Is Pitching, Lopez Isn’t Catching.”

30 Fox Sports South, “Javy Lopez Q&A, Yardbarker.com, https://yardbarker.com/mlb/articles/javy_lopez_q_a/s1_10297_10268746?, accessed February 1, 2017.

31 Roch Kubatko, “Orioles, J. Lopez Agree to Contract,” Baltimore Sun, December 22, 2003.

32 Lopez and Caruso, 116.

33 Associated Press, “Catcher Javy Lopez Retires After Getting Cut by the Braves,” USA Today, March 23, 2008.

34 Fox Sports South, “Javy Lopez Q&A.

35 Lopez and Caruso, 175-176.

36 “Javy Lopez to the Braves HOF,” NotintheHallofFame.com, https://notinhalloffame.com/home/news/4514-javy-lopez-to-the-braves-hof, accessed December 14, 2016.

37 I.J. Rosenberg, “Whatever Happened To: Ex-Brave Javy Lopez.”

38 Lopez and Caruso, 177-178.

39 Bill Zach, “Lopez Finds Escape Through His Planes,” Online Athens, https://onlineathens.com/stories/111900/spo_1119000073.shtml#.WI-x97YrLR0, accessed January 31, 2017; Matt Hennie, “Javy Lopez and His Multi-Million-Dollar Home,” https://projectq.us/atlanta/javy_lopez_and_his_multi-million_dollar_home, accessed January 31, 2017.

40 Lopez and Caruso, 16.

Full Name

Javier Lopez Torres

Born

November 5, 1970 at Ponce, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.