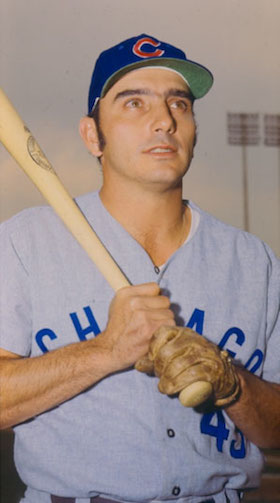

Chris Cannizzaro

“[T]he first major-league pitch I ever called for [was] a curve ball to Wally Moon,” recalled catcher Chris Cannizzaro. “I didn’t catch it. Moon hit it over the left [field] screen of the Coliseum in Los Angeles.”[fn]“’Young Ideas’ by Dick Young,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1973, 14.[/fn] Despite this inauspicious debut, Cannizzaro would go on to build a 13-year major-league career and become the San Diego Padres’ first franchise All-Star. A once-prized prospect, Cannizzaro averaged a scant 150 at-bats per season as a journeyman backstop.

Born on May 3, 1938, in Oakland, California, Christopher John Cannizzaro was raised in the neighboring city of San Leandro.[fn]Professional golfer Tony Lema grew up nearby and was a close friend of Cannizzaro’s.[/fn] The great-grandson of Italian immigrants Angelo and Antonina Cresci Cannizzaro, Chris and his two younger brothers also inherited a strong Spanish heritage from their mother Isabelle Carabello. Their father John was a San Leandro police officer and an accomplished semipro shortstop. Chris followed in his father’s baseball footsteps until his uncle, who managed a Boys Club team, convinced the 11-year-old he was too slow for the middle infield and persuaded him to move to catcher. Chris thrived behind the plate and, in high school, earned all-state honors for the San Leandro Pirates. In the summers he continued play in both American Legion and semi-pro ball and soon began attracting major-league attention. Aggressively scouted by the New York Yankees, Los Angeles Dodgers, Boston Red Sox and St. Louis Cardinals, Cannizzaro leaned strongly toward the Cards, reasoning he had a quicker path to the majors on a team without a Yogi Berra or Roy Campanella. Shortly after his high school graduation in 1956, Cannizzaro inked with Cardinals scout and former minor-league outfielder Tony Governor for an $1,800 salary and a $2,200 bonus.

Cannizzaro ascended rapidly through the Cardinals’ system. In 1958 the right-handed hitter was assigned to the Class AAA Omaha affiliate in the American Association where he thrived under manager Johnny Keane’s guidance of hitting to the opposite field. Though injuries limited Cannizzaro to 106 games behind the plate, his .272 batting average stirred speculation of a next-season major-league promotion. Such talk only intensified when the Class AA Houston Buffaloes secured permission from Texas League officials to use Cannizzaro in the playoffs following a season ending injury to catcher Ray Dabek. On September 9, 1958, Cannizzaro led the Buffaloes to a 13-9 playoff win over the Corpus Christi Giants with three hits (including a home run) and four RBIs.

Any chance Cannizzaro had of capturing a roster spot on the 1959 Cardinals was foiled by a six-month US Army hitch that didn’t end until March 21. Despite an impressive March 30 performance—a triple shy of a cycle—Cannizzaro had missed over three-quarters of spring training. Accordingly, he was reassigned to Omaha where, on Opening Day, he pulled a hamstring, an injury that set the tone for his entire season. Despite selection to the All-Star team Cannizzaro garnered just 268 at-bats after missing more than ten weeks due to a series of nagging injuries. On August 15, with visiting family in the stands, Cannizzaro was hospitalized after taking a fastball to the head. That same month his average dipped to a season-low .225. Despite these setbacks, the Cardinals remained sympathetic: Omaha’s new manager, Joe Schultz, predicted a bright future for his injury-riddled catcher. Once again Cannizzaro’s pending major-league promotion became a conversation topic.

Six backstops were sprinkled among the Cardinals’ 40-man roster in 1960. Hal Smith and Carl Sawatski appeared locked into two of three slated catching slots while Cannizzaro was to compete with fellow prospects Tim McCarver and Gene Oliver for the remaining post. Manager Solly Hemus leaned toward reassigning the 22-year-old to secure fulltime play when, following Cannizzaro’s team-leading .419 spring average, the skipper reversed course. Despite objections from some Cardinals executives, Cannizzaro was retained as the club’s fourth catcher.

On April 17, 1960, Cannizzaro made his major-league debut as a late-inning replacement for Sawatski. Cannizzaro’s first at-bat in MLB was certainly no picnic: he went up against future Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax and grounded to second base. Cannizzaro’s second appearance five days later turned out better again as a late-inning replacement, he collected his first major-league hit, a single to center field against Dodgers righty Ed Rakow. On April 23, Cannizzaro drew the first of three consecutive starting appearances. In the last one in this series of starts proving short-lived after he and Hemus were ejected in the seventh inning after arguing with the umpire over a play at the plate. Cannizzaro also pushed the umpire, a rash move that cost him a $50 fine and a two-game suspension.. He garnered two brief appearances over the next 12 days before being assigned to the Class AAA Rochester Red Wings in the International League. Though he accumulated several errors and passed balls as Rochester’s primary catcher, in a poll of International League managers Cannizzaro earned kudos for showing off the league’s second strongest arm—trailing only future AL backstop Dick Brown. Selected among the Cardinals September call-ups, general manager Bing Devine made it abundantly clear that “[Cannizzaro is] in our plans for the immediate future.”[fn]“‘Draft Curbing Bonus Binge’ – Devine,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1960, 1.[/fn]

Cannizzaro would later claim that he wrote the entire 1961 season off.[fn]“Mets’ Chris Wins Joust With Old Jinx,” ibid., March 27, 1965, 7.[/fn] The Cardinals had tabbed the 23-year-old to juice up the club’s anemic catching corps (a .225-7-45 batting line among six catchers in 1960). But Cannizzaro’s lukewarm spring training performance resulted in his assignment to Houston, where he did not play a single game. On the eve of the American Association’s season opener Cannizzaro was hospitalized with what was originally diagnosed as food poisoning turning into an operation for appendicitis. Cannizzaro lost a month in recovery. On the heels of catcher Jimmie Schaffer’s St. Louis promotion, Cannizzaro was reassigned to the Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League where he shared catching duties with three others. Following McCarver’s July demotion, and despite an unproductive 133 at-bats in Portland, Cannizzaro was promoted to the Cards but used sparingly. Left unprotected in the NL expansion draft that fall, the New York Mets nabbed Cannizzaro on their the 26th pick.[fn]Cannizzaro’s selection was made at the urging of Mets coach and former Cardinals manager Solly Hemus.[/fn]

When the Mets, under the management of the legendary Casey Stengel, reported to spring training in 1962, observers erroneously discerned two clear advantages for the team over their expansion brethren Houston Colt .45s. First, the Mets drafted or acquired primarily older players. Many believed this veteran presence would translate to immediate success on the field. After staggering to a 13-38 record two months into the campaign, Stengel soon began stressing the need for a youth movement. Secondly, the Mets drafted three catchers, including 32-year-old backstop Hobie Landrith as their number one pick overall. The team soon soured on the veteran catcher when opposing teams ran unimpeded on the base paths. Though he struggled offensively, Cannizzaro’s strong armed defensive prowess earned him the starting job. But his hitting was anemic, and he was sent down to the minors. Eventually he would earn the bulk of catching duties, most of which came after return from the minors. Meanwhile the Mets would use seven catchers throughout the team’s inaugural campaign.

In typical Stengel-ese, the manager explained why the player he referred to as “Canzoneri”had been recalled.[fn]The 71-year-old skipper was likely recalling the name of Tony Canzoneri, a 1930s boxer.[/fn] “He can’t hit … [but a] catcher like this kid, who can throw, will let my pitchers pay attention to the hitter instead of worrying about a runner on first base.”[fn]“Case Shelves ‘Name’ Vets – Beckons Kids,” The Sporting News, June 16, 1962, 18.[/fn] To Stengel, “Canzoneri’s” return proved a pleasant surprise as the reinvigorated catcher hit at a .268 pace (team average: .240) through the remainder of the season.

During a road trip to San Francisco, Cannizzaro set an unofficial record for a non-regular by reserving 62 free passes throughout a three-day weekend series, sheepishly disclosing, “I have a lot of relatives out there.”[fn]“Third-Stringer Left Passes For 62 of His Pals, Relative,” ibid., March 27, 1965, 7.[/fn] But most striking were the events that unfolded in the Polo Grounds on September 2 as the Mets nursed a ninth-inning one run lead against the Cardinals. With the tying run on first base, St. Louis manager Johnny Keane inserted speedster Julian Javier to pinch run. Instead of turning to a relief pitcher, Stengel countered by inserting Cannizzaro behind the plate, a prescient move when the “relief catcher” nailed Javier at second in a failed stolen-base attempt, thereby preserving a rare Mets victory. Cannizzaro’s powerful arm led the majors in caught stealing percentage, a mark he attained again in 1965.

Despite this impressive yardstick, the Mets added catcher Norm Sherry to the roster on October 11, 1962, in a purchase from the Dodgers. In this growing gaggle of catchers (another one, Jesse Gonder, was acquired in a trade on July 1, 1963) Cannizzaro would have little opportunity to contend. In the first intra-squad contest in spring camp he suffered a severe fracture to the ring finger of his throwing hand. Unable to catch, Cannizzaro was assigned to the minors for rehabilitation. Though he returned in May, his brief time away opened the door for fellow-expansion draftee Choo-Choo Coleman and Sherry to capture the bulk of catching throughout the 1963 campaign. Cannizzaro was reassigned to the Class AAA Buffalo Bisons.

The opportunity to play full time for the Bisons in the International League was a needed boost for the 25-year-old: “That was the most catching I had done in three seasons. It improved me tremendously. It also gave me a chance to regain my confidence.”[fn]“Mets’ Chris Wins Joust With Old Jinx,” ibid., March 27, 1965, 7.[/fn] A 14-for-25 surge through July 7 that hoisted his average to .316 and contributed to one of Cannizzaro’s finest professional campaigns amply illustrated his renewed confidence. On September 5, in his first starting assignment following his recall to the big leagues, Cannizzaro collected half the Mets hits in a 3-for-3 effort against the Cardinals.

These accomplishments were largely ignored the following spring when Cannizzaro caught a mere 19 spring training innings—a number he exceeded on May 31, 1964, in a single game, a 23-inning marathon versus the Giants. Nonetheless, Cannizzaro was relegated to the far end of the Mets’ bench. After collecting just one pinch-hit appearance through May 4, he eventually began seeing some playing time after Stengel moved yet another catcher—Hawk Taylor—to left field. The opportunity presented by semi-regular usage flowered when Cannizzaro surged to .353 in 102 at-bats through the second half of the season, including a team-leading .330 average on August 21. Cannizzaro credited his success to his roommate, pitcher Frank Lary, who advised the right-handed hitter to be more patient at the plate. Meanwhile, the Mets staff achieved a season-high nine complete games in August before six pitchers marched to the mound during a 12-10 August 28 win against the Chicago Cubs. Following the game,, Cannizzaro quipped “I’ve been getting a lot of kidding about all those complete games. So today, I figured I’d handle the whole staff.”[fn]“Major Flashes – National League,” ibid., September 12, 1964, 27.[/fn]

Though sidelined by a pulled hamstring for the last three weeks, Cannizzaro’s season didn’t go unnoticed.. He dramatically reduced the number of errors and passed balls he’d accumulated in 1962 and, on May 21, tied a major-league record as a catcher by turning an unassisted double play. “Stengel had once said of [Cannizzaro] that ‘he can throw, but he can’t catch.’ This description no longer is true,” wrote The Sporting News contributor Barney Kremenko.[fn]“Lefties Bombed By Hot Licks in Kranepool’s Bat,” ibid., June 27, 1964, 22.[/fn] After the season, the Mets’ skipper gushed about the “amazing the improvement [Cannizzaro] made. All those teams that liked to run the bases—the Dodgers, the Giants—they couldn’t do much with his arm. . . . there was a time when he wasn’t catching it so good. But he does that real well now, too.”[fn]“Ol’ Prof Promotes Mitt Student Chris To No. 1 Met Rating,” ibid., February 13, 1965, 17.[/fn] Bing Devine, now serving as the Mets general manager, echoed Casey’s grammar-challenged compliments: “[Cannizzaro] has come along fine as a catcher. There’s no question that his receiving has improved.”[fn]“Bing Flits From Coast to Coast To Lamp Met Kids, Quiz Scouts,” ibid., October 24, 1964, 20.[/fn] In the spring of 1965, Stengel boldly predicted the Mets’ imminent departure from the NL cellar partially on Cannizzaro’s enhanced work behind the plate.

Cannizzaro entered the 1965 season as one of only four players remaining with the Mets from the original expansion draft.[fn]Al Jackson, Joe Christopher, and Jim Hickman were the remaining holdovers.[/fn] But after securing the starting catching job, Cannizzaro seemingly forgot roommate Lary’s advice about being patient at the plate. Moreover, the season soon became a mirror-opposite of his successful 1964 campaign. He led National League catchers, for example, with 12 errors. On July 23, he was sporting a miserable .176-0-4 line in 176 at-bats when the Mets, with a lousy 31-64 record, replaced Stengel with coach Wes Westrum. Cannizzaro and Westrum had a strong personal bond dating to 1962 when the then-Giant coach graciously advised the Mets catcher that he was tipping his signs to the pitcher. Unfortunately then, it fell to Westrum to announce to the New York press in September that the Mets had completely given up on Cannizzaro.

Uninviting trade offers for the strong-armed catcher soon began pouring into the Met’s front office as clubs attempted to secure Cannizzaro as cheaply as possible. Hall of Fame speedster and famous base-stealer Lou Brock testified to his worth that winter: “As far as the toughest receivers . . . Cannizzaro makes [every stolen base attempt] close even when you get a good jump.”[fn]“Car-Salesman Brock Can Step on the Gas,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1965, 19.[/fn] On April 5, 1966 Cannizzaro was traded to the Atlanta Braves’ Triple-A affiliate in Richmond, Virginia, for infielder Don Dillard and an undisclosed cash amount.

From 1966-68 Cannizzaro bounced among four minor-league organizations collecting time at catcher, third base, first base, and the outfield. Cannizzaro was selected to the 1967 International League All-Star squad—alongside onetime Mets teammate Jesse Gonder[fn]Gonder’s career seemingly shadowed Cannizzaro’s. Both were raised in the Oakland and made their MLB debuts the same year. Though Gonder never played a game with the Padres, he was initially listed on San Diego’s 1969 Opening Day roster alongside Cannizzaro.[/fn] —while leading the Toledo Mud Hens to the Governor’s Cup championship. That spring he had competed for the backup role behind the Detroit Tigers Bill Freehan and, in 1968, was invited to the Pittsburgh Pirates spring camp as a non-roster invitee. The Pirates assigned him to the Class AAA Columbus Jets. On July 31, 1968, Cannizzaro collected a single-game career-high six RBIs (two three-run homers) while leading his team to a 13-3 rout over the Buffalo Bisons.

This success, combined with the second-half slump of Pirates catcher Jerry May, resulted in Cannizzaro’s recall to the majors. On August 17 Cannizzaro collected his first major-league home run in leading the Pirates to a 3-0 victory over the Dodgers. Two weeks later he added a decisive tenth-inning RBI single to his two-month resume in a 4-3 win over the Houston Astros. Cannizzaro received 18 starting assignments and secured 58 at-bats, including a brief 7-for-14 surge in September. Delighted to be back in the majors, Cannizzaro was even happier the following spring when he was traded to the San Diego Padres in a four-player swap. As he later explained, “It was the biggest break of my career. . . . It gave me the chance to play every day.”[fn]“Mitt Flash Cannizzaro Shocks Hurlers With Hit Barrage,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1969, 19.[/fn] The move also placed the well-traveled catcher closer to his growing family.

Ten years earlier, Omaha Cardinals first baseman Walt Matthews set up his teammate Cannizzaro on a blind date with Beverly Goff. A Regina, Saskatchewan, native, the Omaha-based Ozark Airlines flight attendant was a roommate of Matthews’ girlfriend. The date went swimmingly: the two eventually fell in love, married, and settled in San Leandro. On February 23, 1962, Beverly delivered their first child, Christopher Jr. Cannizzaro would not see his son for two months since he was in Florida competing for a roster spot with the expansion Mets. Twenty-one years later Chris Jr., a ninth-round selection of the Boston Red Sox, would launch a seven-year professional career of his own.

In spring 1969, for the second time in his career, Cannizzaro found himself vying for a roster spot with an expansion club. In an exhibition game two days before the start of the season, the slow-footed receiver made a positive impression on Padres fans by running out an inside-the-park homer against the Cincinnati Reds in cavernous San Diego Stadium. Cannizzaro won the starting catching job and proved a workhorse behind the plate, behind the plate in 67 of the team’s first 74 games. He started slowly at the plate but countered with a .333 surge in May. His .276 pace on June 8 trailed only first baseman Nate Colbert for the team lead and resulted in Cannizzaro’s selection as the franchise’s first All-Star representative. Though he slumped to a dismal .170 in the season’s second half— manager Preston Gomez attributed the slump to exhaustion from his ironman role behind the plate—Cannizzaro finished the year with single-season career highs in games played (134), plate appearances (469), at-bats (418) and doubles (14). He also received praise for his work with the young pitching staff. His success in the Padres inaugural campaign prompted Cannizzaro’s purchase of a San Diego residence that winter. And in January 1970, he was discovered working out in San Diego Stadium well before the February 15 reporting date for spring training.

In March Cannizzaro played the role of savior[fn]A year later Cannizzaro resurrected this role when Los Angeles columnist Bud Tucker was found choking on a piece of meat. With brute strength he lifted Tucker by the ankles and shook him until the meat was dislodged.[/fn] to some of his stranded teammates. The Padres had traveled to Mexico City to play out a portion of the exhibition season. Lodged at the Casa Blanca Hotel, Cannizzaro and a group of teammates became stuck in a hotel elevator between the third and fourth floors. Cannizzaro and coach Roger Craig crawled through an escape hatch to find help for their stranded cohorts. As it turned out, this was not the only challenge Cannizzaro faced that spring.

On December 5, 1969, the Padres acquired catcher Bob Barton from the Giants in a four-player transaction. San Diego hoped to platoon Barton behind the plate in 1970 to provide their starting catcher much-needed —though from Cannizzaro’s perspective, much-unwanted—rest. The spring competition fizzled out when Barton was briefly sidelined with a left forearm injury while Cannizzaro smacked the ball at a .435 pace. The brisk start followed Cannizzaro into the regular season. On May 8, two days after completing a nine-game hitting tear, he initiated a season-best 13-game hitting streak. Although he had a .328 average on July 7, Cannizzaro was passed over for an All-Star nod. He finished the campaign with single-season career highs in runs scored (27), hits (95), and RBIs (48). Despite this success, the Padres were telegraphing a different future. They chose catcher Mike Ivie as their number one overall selection in the amateur draft while, in September, general manager Buzzie Bavasi identified 32-year-old Cannizzaro as one of the team’s most marketable trade assets.

On May 18, 1971, the Padres traded Cannizzaro to the Chicago Cubs for infield prospect Garry Jestadt. Over the next three years he bounced among four organizations, including a return to the Padres. Secured by the Cubs to temporarily spell injured backstop Randy Hundley, Cannizzaro shouldered the bulk of the team’s catching duties in 1971. The same situation developed in Los Angeles the next year when Dodgers’ catcher Duke Sims was slow to recover from injury. The Dodgers were pleased by the mentoring role Cannizzaro played for budding youngsters Steve Yeager and Joe Ferguson. As general manager Al Campanis exclaimed, “There’s no question about either [Cannizzaro’s] knowledge of the game or his ability to handle pitchers.”[fn]“Battling Cannizzaro Buoys Dodgers,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1972, 13.[/fn] Used sparingly in 1973, Cannizzaro’s bonhomie and leadership skills made him one of the team’s most popular players. When he didn’t collect his first hit of the season until June 28, he received a mock standing ovation from the Dodgers’ dugout. Amid this camaraderie Cannizzaro’s name began surfacing as a future managerial candidate.

The managerial speculation surprised few. Cannizzaro had exhibited strong leadership skills from early in his career including successfully arguing a reversal of Cardinals infielder Jerry Buchek’s home run on July 17, 1965 (Buchek was awarded a double while Cannizzaro—who was not playing—was rewarded with an ejection). Serving as a player-coach for Class AAA Denver Bears in 1974, Cannizzaro earned his first opportunity as skipper on June 1, 1974. As the Bears acting manager when Frank Verdi was called away for personal reasons, Cannizzaro led the Bears to a 3-2 victory over the Omaha Royals. He received praise from pitcher Michael Flanagan (a Detroit native and career minor leaguer, not the Mike Flanagan with an 18-year big-league career, 15 of them pitching for Baltimore) for helping the righty hurler improve command of his pitches and, following his August return to San Diego, Cannizzaro was cited for his work with budding catching prospect Bob Davis.

In 1975 Cannizzaro served as player-coach for the Hawaii Islanders in the Pacific Coast League where, for the fifth time, he teamed with journeyman hurler Bob Miller. A year later he was hired as the bullpen coach by the Braves. He served under four skippers (including owner Ted Turner’s one-game managerial experiment in 1977) while also mentoring 22-year-old Bruce Benedict in 1978. Released by the Braves in October 1978, Cannizzaro signed with the California Angels as a coach and for three seasons manager in the Class A California League. In this latter capacity he ushered the careers of Mike Witt, Tom Brunansky, and Dick Schofield. Managerial stops in Salinas and Redwood placed Cannizzaro close to his San Diego home where he eventually retired.[fn]Miller and Cannizzaro previous played together on: the 1960-61 Cardinals, the 1962 Mets, and both the Padres and Cubs in 1971.[/fn]

Throughout his career Cannizzaro participated in numerous charitable and reunion events. In 1965 he played in a benefit game on behalf of the widow of San Francisco’s clubhouse custodian where $8,000 was raised (that same year his wife participated in a charity fashion show in New York). Five years later he was recognized as “Big Brother of the Year” in San Diego. Cannizzaro travelled to New York in 1986 to engage in an Old Timers Game with many of his former 1962 Mets teammates. A decade later he launched a 10-year stint as an assistant baseball coach at the high school and collegiate levels. He even tried to come to the aid of the men in blue on one occasion. On April 21, 1965, home plate umpire Bill Williams, in a seeming act of desperation, pleaded with Cannizzaro to prevent manager Casey Stengel from continually coming out of the dugout. On this occasion Cannizzaro’s efforts proved fruitless when Stengel was thumbed from the game.

On July 12, 2016, the Padres honored Cannizzaro as the franchise’s first All Star representative when San Diego hosted the 2016 midsummer classic. Five months later, on December 30, Cannizzaro died at his home in San Diego after a long battle with lung cancer. He was survived by Chris Jr., a second son, a daughter, his second wife (the marriage to Beverly having ended in divorce years earlier), two stepdaughters, and 11 grandchildren.[fn]Kirk Kenney, “Chris Cannizzaro, First Padres All-Star, dies,” The San Diego Union Tribune, December 30, 2016. Accessed January 8, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2i7fBOH).[/fn]

At one stage during his career Cannizzaro bristled after being labeled a good-fielding, poor-hitting catcher. “You’ve got to be in there all the time to get into the groove. Otherwise you get rusty,” he exclaimed.[fn]“Quiz Kids’ Snappy Performances Make Ol’ Perfessor Smile,” ibid., September 21, 1963, 16.[/fn] But Cannizzaro was rarely given the opportunity to be in there all the time. Frequently platooned, he played in 740 games (an average 57 games per year) over a 13-year major-league career. Cannizzaro’s .235-18-169 batting line in 1,950 at-bats fell considerably short of the once-glowing expectations from manager Solly Hemus and Casey Stengel. But his reputation as a top-grade analyst, a field leader, and a mentor to his younger assigns made the California-native a valued asset and cherished teammate throughout his long career.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank SABR members Tom Schott and Mark Pattison for editorial assistance, and Mark also for fact-checking assistance.

Additional Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball-reference.com

Full Name

Christopher John Cannizzaro

Born

May 3, 1938 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

December 29, 2016 at San Diego, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.