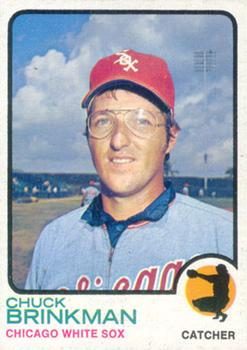

Chuck Brinkman

Charles Ernest Brinkman spent parts of six seasons as a backup catcher in the major leagues, all but four games of the last season with the Chicago White Sox. Despite a .172 career average, he remained in the majors as long as he did on the strength of his stellar defense.

Charles Ernest Brinkman spent parts of six seasons as a backup catcher in the major leagues, all but four games of the last season with the Chicago White Sox. Despite a .172 career average, he remained in the majors as long as he did on the strength of his stellar defense.

As a collegian at Ohio State, he reached the finals in two consecutive College World Series with the Buckeyes, winning the championship in 1966, and was selected to the All-Tournament team both times.1

Brinkman was born into a family of Dutch descent in Cincinnati on September 16, 1944—his mother’s birthday. His older brother, Ed Brinkman, spent 15 years in the majors as a slick fielding shortstop, mostly with the Washington Senators and Detroit Tigers. The brothers’ parents were Edwin Brinkman, a die setter in a Cincinnati factory, and the former Marie A. Roth, a seamstress for a tie manufacturer.2

Brinkman began catching as a 9-year-old in Little League. “I saw the catcher’s equipment (lying) out there,” he told Jerome Holtzman in The Sporting News. “I said to myself, ‘Well, I’m going to give it a try.’” To earn money as a youth, he worked at a local grocer, stocking shelves and delivering groceries.3

Like his brother, Chuck Brinkman starred in baseball at Western Hills High in Cincinnati, a school that produced Pete Rose and eight other major leaguers. Chuck, like his brother, was the captain of the Western Hills basketball team. Brinkman caught for an American Legion team that finished second in the national tournament in 1961. He played Legion ball again in 1962, and by the time he finished high school, the right-handed batter was 6-foot-1.4

He enrolled at Ohio State after high school and played on the varsity baseball team. The Buckeyes lost in the finals to Arizona State in ’65, but defeated Oklahoma State the following year for the national championship. He hit .450 in that tournament. Brinkman graduated from Ohio State with a Bachelor of Science degree in education.5

On June 7, 1966, the White Sox selected him in the 16th round of the amateur draft and Sox scout Fred Shaffer signed him. Sent to Lynchburg in the Class A Carolina League, he hit .186 in 47 games. Not a power hitter, Brinkman finished without a home run his first two seasons. He hit better, however, at Appleton in the Class A Midwest League in 1967 — .260 with a .324 on-base percentage in 103 games. He was selected as a league all-star and named the most valuable player on Appleton’s championship team. Back at Lynchburg in 1968, he batted just .204, but he hit the only minor league home run he would collect in 1,454 plate appearances. Clearly, Brinkman’s value was his defense. 6

Brinkman taught school as a physical education teacher in Oxon Hill, Maryland, a Washington, D.C., suburb, during the 1968-69 off season, in a job he found after visiting his brother, who was with the Senators then. Brinkman got married early in 1970. He and his wife, the former Carol Terry, had a daughter Lisa later that year and a son Jeffrey in 1973. Jeffrey was a catcher for four years at Ashland (Ohio) University. His team reached the Division II college world series in 1995.7

At age 24, Brinkman debuted in the majors on July 10, 1969, at Comiskey Park. He had been called up to fill in for injuries. Brinkman struck out as a pinch-hitter against Blue Moon Odom. His first major league hit—indeed, his only one in 18 plate appearances that season—came against the Indians’ Larry Burchart in the eighth inning of an 11-6 White Sox victory in Cleveland on July 30. He also went on to score his first big league run that inning after having entered the game in the sixth as a defensive replacement. He didn’t start behind the plate that season or appear in a game after September 2, even though he remained on the Sox roster.8

Brinkman split the balance of the 1969 season between Tucson in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League and Columbus in the AA Southern League, hitting a combined .237 in 51 games. His first major league start came on May10, 1970, in a loss to the Orioles in Baltimore. He started again on May 27, but spent most of the summer at Tucson. Recalled in September, he made four starts behind the plate and had five hits, which raised his average to .250 in 23 plate appearance. That turned out to be his career best.

Brinkman stayed with the White Sox during the entire 1971-73 seasons. To say he was used sparingly the first two full seasons would be an understatement: he appeared in just 15 games in 1971, sitting on the bench from August 2–September 29. But White Sox manager Chuck Tanner touted the third-string catcher’s importance to the team. “As long as I have Brinkman, I always can pinch-run for (Ed) Herrmann or (Tom) Egan … and I know I still have a man on the bench who is without a doubt one of the best catchers and throwers in the league. … I figure he’s helped us win six to eight games—just by being there.” Tanner was also high on Brinkman’s defensive prowess. “That guy is like a brick wall behind home plate,” he said when Brinkman made the Sox in 1971. “He catches them easily even when they’re into the dirt.” Tanner had taken a liking to Brinkman in Hawaii when the catcher was with Tuscon and Tanner was managing the Islanders. One off day there, Tanner asked Brinkman to join in a workout. “He took an interest in me then,” Brinkman said, so it was a happy coincidence when Tanner became the Sox manager.9 Brinkman also was put to considerable use by White Sox pitching coach Johnny Sain, who believed in having his pitchers throw every day in the bullpen. “He didn’t make them throw hard or break off sharp curves, but he had them throw,” Brinkman said.10

White Sox knuckleballer Wilbur Wood was a big Brinkman fan. The catcher would warm up Wood before games and keep an eye on him throughout. “Chuck would spot things,” the Sox ace told a reporter in 1975. When Wood was slumping, “he told me I was pushing the ball instead of throwing it. It was a bad habit. . . . Brinkman started coming out on the field early and helping me.” For Wood, the release point on his knuckler was crucial, the catcher said.11In addition to the knuckler, “Wilbur had a good curve and a fastball. . . . I still have the glove I used to catch him,” Brinkman said in 2018. “It was one of those pancake ones with no webbing,” but “not much bigger than the ones they use today.” As much as he liked Wood, Brinkman conceded that, even for him, catching the knuckleball was a challenge.12 Anxious to get playing time, Brinkman went to Venezuela for winter ball in December 1971. He and the four other Americans with first-place Argua were released late in the season and sent home, accused of pressuring team management to pay them postseason bonuses. They denied the charge, but were banned from the league for life. Brinkman recalled the American players — his wife and infant daughter also were there — being escorted to the airport with armed guards protecting them. MLB concluded that the players had done nothing wrong.13

After playing in 35 games in 1972, Brinkman saw more action in ’73, a season in which he roomed on the road with young shortstop Bucky Dent. Brinkman appeared in a career-high 63 games as Herrmann’s main backup. “There’s not a better backup catcher in baseball,” Tanner said in January 1974. The numbers bore him out: Brinkman threw out 18 of 43 would-be base-stealers, or 41.9 percent, in 1973. Indeed, his career caught-stealing percentage was a sterling 38.4 percent.14

The young catcher hit his only major-league homer on May 22, 1973, against Rudy May of the Angels in a 6-2 win that kept the White Sox in first place. Newspapers reported that his teammates retrieved the home run ball and left in a plastic case at his locker the next day. “These guys are great,” Brinkman said, puzzled at how his teammates found a home-run ball that went into the bleachers. “I’ll remember my first home run in the majors a long, long time.” He couldn’t know then that his first dinger would be his only one. (He had hit his only spring training home run off Tom Seaver in March the year before.)15

Brinkman landed on the disabled list to start the 1974 season after spraining a knee near the end of spring training. He had been to bat just 14 times for Chicago when the Pittsburgh Pirates acquired Brinkman for cash on July 11, 1974, to fill in injured backup catcher Mike Ryan. “He’s not an offensive player,” Pirate GM Joe L. Brown said of Brinkman, but “he can catch, throw and handle pitchers.”16

At age 29, his start at catcher on August 4, 1974, was his last major league appearance. Once Ryan returned, the Pirates optioned Brinkman to AAA Charleston in the International League.17 The 21 games he played there that season were his last in pro ball. He suffered a left shoulder separation in a late August play at the plate and spent the rest of the minor league season on the disabled list.18

The Pirates helped along his decision to retire in late October by assigning his contract to Charleston. On the positive side, however, Brinkman in May had amassed enough big-league time to qualify for a pension.19 “I celebrated a bit that day.”20

Brinkman passed up a last shot at the majors. In early December, the Twins thought they had a deal with the Pirates to acquire Brinkman, but by then he had taken a job as a sales representative with Ohio Art, the toy company that made Etch-A-Sketch.21 “He said no thanks…. He would rather stay in the sales business,” Minnesota farm director George Brophy told a Minneapolis reporter.22 Brinkman had begun selling toys for Hasbro in the off-season while he was with the White Sox.23

In 2001, in recognition of his outstanding college career, Brinkman was inducted into Ohio State’s Varsity “O” Hall of Fame. His Varsity “O” biography calls him “the finest catcher in Ohio State history.” The Buckeyes were 78-29-1 during his three years on varsity, and he was the captain of the ’66 championship team. In 2016, he and his teammates reunited for the event’s 50th anniversary. In 1996, Brinkman was named to the College World Series All-Decade team for the 1960s. He had been a second-team All-America in 1966.24

As of August 2018, Brinkman continues to run his own sporting goods wholesale business from his home in Bryan, Ohio, a county seat between Fort Wayne and Toledo in the northwestern part of the state. He and his wife of 48 years have lived in their home there for decades.

Brinkman said he rarely gets to a big league game but sometimes drives to Toledo to see the Triple A Mud Hens or to Fort Wayne to see the Class A team there. “I can park my car for $5 and pay $4 for a beer,” he joked. He has season tickets to Ohio State football games and often stays with college friends when he goes.

“The catcher is the most important position on the field. He has everything right in front of him,” Brinkman said about how he saw his role. “My brother always told me you had to be really strong in one area,” if you weren’t good at everything, Brinkman said. “We called our own pitches back then. … I could catch and I had a strong arm.” It was enough to keep him in the majors long enough to earn a pension.25

Last revised: November 28, 2018

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Chuck Brinkman for his help with this biography, which was edited by Tom Schott and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

Career statistics and game results from BaseballReference.com and Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Telephone conversation, author with Chuck Brinkman, August 30, 2018.

2 Chuck Brinkman’s player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

3 Jerome Holtzman, “Sub Catcher Brinkman Unsung Hero of Chisox,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1971: 17; see note 1.

4 John Cannon, “Talk of the Teens,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 11, 1962: 43; Gary Schultz, “Budde On Top In Legion Race,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 23, 1962: 22.

5 Jim Van Valkenburg, “Ohio State Defeats OSU in Title Game,” [Pocatello] Idaho State Journal, June 20, 1966: 7; Brinkman’s Hall of Fame file.

6 See note 2.

7 Ibid

8 Ibid.

9 “White Sox Send Ex-Cat Hinton to Toros,” Tucson Daily Citizen, March 31, 1971: 54.

10 See note 1.

11 John Brockmann, “Same Old Tanner . . . He’s Still Optimistic About Sox,” Sarasota FL Herald Tribune, February 27, 1975: 50; ibid.

12 See note 1.

13 Eduardo Moncada, “Zulia Pitching Staff Shows Zip Under Billings,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1972: 47; ibid.

14 Roger Farrell, [De Kalb, IL] Daily Chronicle, January 16, 1974: 17.

15 “Brinkman Keeps Sox in First Place,” Lakeland Ledger, May 23, 1973: 1B; “Chisox’ Bahnsen Wins Sixth With Three-Home Run Help,” [Lafayette, IN] Journal and Courier, May 23, 1973: 37; Georg Langford, “Orta Leaves ’Em Talking; Sox Win, 6-1,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1972: 106.

16 “Bucs Purchase Sox’ Brinkman,” Pittsburgh Press, July 11, 1974: 23.

17 “Brinkman Sent Down by Bucs,” Indiana [PA] Gazette, August 7, 1974: 19.

18 Bill Smith, “Catch Rule Catches Outfielder,” Charleston [WV] Daily Mail, August 23, 1974: 1D.

19 “Sox Notes,” Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1974: 87.

20 See note 1.

21 Ibid.

22 Chan Keith, “Catcher rejects Twins to keep selling toys,” Minneapolis Star, December 4, 1974: 81.

23 Ron Bergman, “’Lucky to Be Back With A’s,’ Beams Toy-Vendor Lindblad,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1972: 42.

24 https://www.ohiostatebuckeyes.com/trads/men-varsityo-hof.html

25 Previous paragraphs based upon telephone conversation, author with Brinkman, August 30, 2018.

Full Name

Charles Ernest Brinkman

Born

September 16, 1944 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.