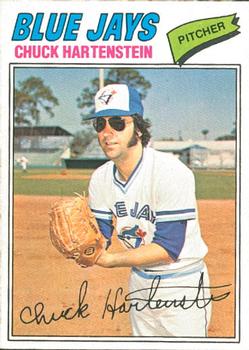

Chuck Hartenstein

Right-handed pitcher Chuck Hartenstein was a good, solid minor-league pitcher who enjoyed significant success in the National League, but struggled in the American League. He later moved on to work as Toronto’s minor-league pitching instructor and the major-league pitching coach for the Cleveland Indians and Milwaukee Brewers. Basically, Hartenstein reached the major-league level in three different ways — as a pitcher, a pitching coach, and a major-league advance scout.

Right-handed pitcher Chuck Hartenstein was a good, solid minor-league pitcher who enjoyed significant success in the National League, but struggled in the American League. He later moved on to work as Toronto’s minor-league pitching instructor and the major-league pitching coach for the Cleveland Indians and Milwaukee Brewers. Basically, Hartenstein reached the major-league level in three different ways — as a pitcher, a pitching coach, and a major-league advance scout.

A Canadian website pointed out he was the only person in a big-league uniform for the first game at Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium and also the first game at SkyDome.1

Charles Oscar Hartenstein was of German ancestry, a native of Seguin, Texas, the county seat of Guadalupe County, about 35 miles east of San Antonio and about 60 miles almost due south of Austin. He signed his name Charlie Jr. In a May 2018 interview, Hartenstein said, “My father worked for a distributor and he delivered Lone Star Beer and Falstaff Beer to all the bars and restaurants in Seguin, Texas.”2 His mother, Lois Myrtle Springs Hartenstein, was a teacher who taught at the local Catholic school and later at public schools. Charlie Jr. was born on May 26, 1942. He had a younger brother, Larry, who was born about six years later.

“I went to a Catholic school. I’m not a Catholic but the reason was, we grew up poor. For Christmas, my present would be a rubber ball. We struggled. The Catholic school was about 2½ blocks from my home. We didn’t have transportation for me to go to any of the other elementary schools. I went to the Catholic school from the first through the eighth grade. It was convenient. I enjoyed it. I learned a lot about a lot of things.”

He attended St. Joseph’s Catholic School for the first eight grades, playing Little League, Pony League ball. He was obsessed with baseball from an early age, throwing rocks all day over a makeshift home plate, then gathering up the rocks and bringing them back to throw again. He used his mother’s broomsticks, every time she got a new broom, and hit rocks with the broomstick. “I could wear out a mop or a broom in about a week,” he said.3

He played American Legion ball, too, and attended Seguin High School. He played baseball, football, and track. He went on to the University of Texas for four years and earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration and marketing, playing under legendary coach Bibb Falk on a four-year baseball scholarship.

There had been a number of scouts looking him over during his high school days — and no wonder. In the state high school finals at Austin, he defeated Kilgore one day, 3-1, and the very next day threw a 3-0 no-hitter against Snyder in the title game. Hartenstein was a unanimous choice for All-State in his senior year. The Tigers offered him a “pretty good bonus” but he declined, in order to take the U.T. scholarship offer. He was 18-6 in his time at the university, fending off another bonus offer from the Phillies. “I couldn’t accept it,” he said a few years later, “since I promised Mr. Falk that I would fulfill the four-year scholarship.”4 He continued, “Then these clubs apparently forgot about me. At least I didn’t hear from them again.”5 In fact, he started calling the scouts, taking their telephone numbers from business cards that had been left with him. By that time, many of their rosters were full, perhaps a combination of unfortunate timing and insufficient interest.

One scout, however, Billy Capps of the Chicago Cubs, called him back a bit later. “He said, ‘Charlie, here’s what I can do. I can give you $500 a month and you go play for St. Cloud.’ I said, ‘Billy, I can’t do that. I’m within just a few hours of graduating from U.T. and I can make a whole lot more money.’ I had gone down in February or March to the Buick dealer here in Austin and ordered a fast V-8 Buick Skylark. The car cost around $3,000. When Capps offered me the $500, I said, ‘I just can’t do that.’ I told him I’d ordered this car and the dealer kept calling and saying. ‘We’re got this car. When are you going to come pick it up?’ I said, ‘If you don’t mind, just give me a little more time. I’m negotiating.’ We worked out a deal. I talked him into like $1,500 as my bonus. He said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll give you the progressive bonus.’ A progressive bonus was like $7,500 — but you had to earn it over time. You had to play 90 days at Double A for a thousand. Ninety days at Triple A for $1,500. And then after 90 days in the big leagues, you got $5,000. It was a bonus — but, boy, it had some strings on it. I ended up, within three years, getting all three of those.”

He signed with the Cubs on May 28, 1964, with the bonus reported at the time as the full $7,500.6

He had racked up a number of distinctions before graduating and signing. In both 1962 and 1963, he had helped pitch Texas to Southwest Conference and NCAA District Six championships. In the 1962 College World Series, he beat Colorado State, 7-2, losing to Santa Clara in 10 innings, 4-3. on errors. In the 19 innings, he’d struck out 18, walked only one, and only three of the six runs he’d allowed were earned runs. In 1963, he returned to the College World Series, losing his only game, 3-2, to Missouri; all three runs were unearned. During the summer of 1963 he was busy; he pitched in the Central Illinois Collegiate League for Champaign-Urbana (9-2, 2.03 ERA), leading the league in wins. Right afterward, he got a call inviting him to join the Alaska Goldpanners, meeting up with them not in Fairbanks but in Wichita for the National Baseball Congress. In Wichita, he won three complete games, with an ERA of 1.56, helping the Goldpanners to a third-place finish.

Hartenstein was already a married man by this time. He wed Joyce Elaine Engelke in Guadalupe on November 26, 1961.

His first professional assignment was with the 1964 St. Cloud (Minnesota) Rox, in the Class-A Northern League. He was 8-5 with a 3.27 ERA, striking out 82 batters in 113 innings, walking 46.

Advanced to Double A in 1965, he pitched for the Texas League Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs. Again he walked 46 batters, but this time struck out 119 in 223 innings. He was 12-7 with a 2.18 earned run average. One game to remember was the longest game in Texas League history; on June 17, 1965. he pitched the first 18 innings of a 25-inning game against Austin. The score was 1-1 when he left for a pinch-hitter; Austin prevailed in the end, 2-1.

Hartenstein was beckoned to the big leagues by the Cubs in September. The day he arrived was September 9, joining the team at Dodger Stadium. It was quite a game to see. The Cubs’ Bob Hendley threw a one-hitter, only to be upstaged by Sandy Koufax, who threw a perfect game.

But the only duty he saw that first year was a very brief one, and it was not as a pitcher. On Saturday afternoon September 11, 1965, his major-league debut was in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. The Giants held a 6-4 lead over the Cubs after six innings. Masanori Murakami entered in the top of the seventh, in relief of starter Bob Shaw. He gave up a pinch-hit single, then struck out the next batter. The third batter, another pinch-hitter, also struck out. The Cubs were pulling out all the stops. A third pinch-hitter, John Boccabella, singled. There were runners on first and second, but with two outs. Cubs manager Lou Klein made two moves. He asked Hartenstein to pinch-run for Boccabella and Joey Amalfitano to pinch-hit, the fourth pinch-hitter of the frame. Murakami hit Amalfitano, so both baserunners advanced a base, Hartenstein making his way to second base. Glenn Beckert then flied out to second base, ending the threat. The game finished 6-4. Hartenstein had moved 90 feet, from first base to second. That was the sum total of his 1965 action in the majors.

He would have been kept longer but he had just come off a playoff game in Texas and suffered a shoulder injury. By early spring training 1966 at Long Beach, he was only throwing maybe 60 miles per hour and was in pain doing so. He asked his wife Joyce to take movies of him warming up. Given the technology of the time, it took about four days to get the film developed but he immediately spotted the problem. “I saw the trouble,” he said. “I was favoring my shoulder so much I was pushing the ball instead of throwing it. For the next few weeks, I concentrated on just throwing the ball, I exaggerated it. It hurt plenty. But it stretched the tendons back to where they should have been.”7 He added, “About 10 days to two weeks later, I was the starting pitcher on Opening Day in Tacoma. That made me realize how important the video part of this game really is.”8 Video became an important teaching tool in his later work as a pitching coach.

In 1966, Hartenstein pitched in Triple A for the Tacoma Cubs in the Pacific Coast League. His won/loss record (3-10) to some extent reflected their last-place finish in the West Division standings, but his earned run average was a good 2.94. He started 17 games and relieved in 21 others, converting to a reliever in midseason after a groin injury put him in the bullpen. The Cubs called him back to the big leagues in September.

This time, he got some mound work in, appearing in five games. On September 13, he threw his first three innings in the majors, at Wrigley against the visiting Atlanta Braves, working the sixth, seventh, and eighth innings. The score was 9-1, Atlanta, when he began, and 10-1 when he left for a pinch-hitter. Eddie Mathews doubled in Felipe Alou for he one run he surrendered.

He gave up another run in a two-inning stint on September 16, but then no runs at all the next three times he pitched, and only one hit over those three outings. His record shows no decisions, 9 1/3 innings pitched, and a 1.93 ERA.

Hartenstein opened the 1967 season back with Tacoma; he was 3-2 (3.94) in the early going, but was summoned to the major leagues in early June and worked his first game on June 6. It was a tie game against the Phillies, 6-6, when Cubs manager Leo Durocher asked him to pitch the bottom of the eighth. He gave up back-to-back singles to the only two batters he faced, but the lead runner was caught trying to advance to third. The remaining runner later scored, off of Cal Koonce. Hartenstein received his first decision, a loss. He evened his record with his first win, five days later. He’d had a scoreless two-inning stint on June 9. There was a doubleheader against the Mets on the 11th. In the second game of a high-scoring 18-10 Cubs win at Wrigley, he took over for Koonce, after Koonce had been lifted for pinch-hitter Boccabella. He worked the third inning through the eighth inning, watching the Cubs build an 18-5 lead while he gave up just one run in his first six innings. The 18th run was one he drove in himself, singling to score Adolfo Phillips. Durocher left him in one inning too long. In the top of the ninth, he gave up a homer, a double, a homer, and a walk, and then was removed. Though he was charged with five earned runs, he got the win.

Another win followed, and another, and at the end of June he was 3-1 with three saves. He’d earned headlines such as “HARTENSTEIN SAVES GAME IN PITTSBURGH: Rookie Brilliant in Relief Role Hartenstein’s Fine Relief Pitching Defeats Pirates” — that one for his work in the June 20 game, pitching 4 2/3 innings of scoreless relief.9

July saw two more wins and five more saves. By season’s end, he had worked in 45 games, all in relief, closing 30 of them. He was 9-5 with 11 saves in 1967, with a 3.08 earned run average. It was his best year in major-league baseball.

Other than Chuck, he also attracted the nickname “Twiggy” at one point, due to his wiry 5-foot-11 and 150-pound frame. Jerome Holtzman said it was “The Monster” Dick Radatz who “hung the name on him.”10 But it was actually Billy Williams who had bestowed it, Hartenstein said in his 2018 interview. “His locker was next to me. I got a save or something that day and there is a bunch of writers gathered around the locker and Billy looks at me and says, ‘Twiggy!’ It caught on with the writers.”

Hartenstein didn’t mind the nickname. He kind of liked it, musing in 1967, “I wonder if there’s ever been a big league pitcher who weighed less.”11 Another time he said, “I was happy to get the recognition. Most ballplayers look alike…it gave me some identity.”12

With as much work as he’d been given, he was accorded another nickname that summer: “Mr Every Day.” Hartenstein praised Billy Capps for signing him: “Mr. Capps followed me through the last two years of my high school competition, and most of the time when I was a student at the University of Texas. After I graduated, he was the only scout I heard from…He was very frank, saying, ‘I can’t offer you very much money, but I can assure you a full chance since the Cubs are hard pressed for young pitchers.’ He kept his promise, and the Cubs gave me every possible chance to make good.”13

He was fine with all the work, he said. The more work he was given, the more tired he got and that was good for his sinkerball. “The slower I throw it, the more it dips. If you throw it too hard, it gets to the plate too fast.”14 He credited Fred Martin with teaching him the sinker, and he credited Elmer Singleton, his pitching coach with Tacoma, with teaching him poise and confidence.

His 1968 was something of a mirror image of ‘67, in that he started the season with the Cubs and in June returned to Tacoma. He appeared in 27 games for Chicago and was 2-4. He was bringing his ERA down slowly but steadily, from 6.75 at the end of April to 5.09 at the end of May, and then to 4.05 as of June 23, when he lost his fourth game. In late June, the Cubs made a flurry of deals all at once. They traded Lou Johnson to the Indians for Willie Smith, bought Bob Oliver from the Red Sox, recalled Bill Stoneman from Tacoma, and sent both Boccabella and Hartenstein to Tacoma.15 With Tacoma, he was also 2-4 but with a 1.86 ERA. He came back up briefly in September and got in one game, on September 2, but gave up three runs in 2 1/3 innings. After the game, he found himself offered a ticket back home. He explained:

As a matter of fact, Leo Durocher and I just did not see eye to eye. In ’67, I had a great year for him. I was 9-5 and have 10 saves or whatever it was. I go to spring training with them in ’68 and the pitching coach was Joe Becker, and the days that I was scheduled to get an inning’s work here or there, Joe would always come out and say, “Hey, get your work in on the side. Leo wants to see these other guys.” When the season opened, I wasn’t ready. My arm was fine, but unless you face hitters in spring training, you don’t really get ready and I wasn’t. It just showed up. I struggled that first half. Me and John Boccabella got sent to Tacoma.

When we came back up, both of us had been flying all night to get back there from Tacoma to Chicago. We were playing San Francisco at the time and at some point in the game, they brought me in. I got a few guys out here and there and then Jack Hiatt — their catcher — I got a ball up to him and he hit a fly ball to right that dropped into the bleachers.

As soon as the game was over, we were walking out and the traveling secretary hands me an envelope. I said, “What is this?” He said, “Leo didn’t talk to you? Well, this is your ticket to go home.” I went right from there to Leo’s office. He and I had a…discussion. it was probably a little louder than most. Then I went upstairs to the GM, Mr. [John] Holland, and I said, “Mr. Holland, I hate to have to ask you this. You guys have treated me great all the way through, but I just cannot get along with your manager. Would you please trade me?” Sometime during the offseason, they traded me to Pittsburgh.16

Early in 1969, he was joined by utility infielder Ron Campbell in a trade to the Pittsburgh Pirates — where he joined fellow Seguin native Freddie Patek –.for Manny Jimenez. Campbell played the next two seasons with Triple-A Columbus and never returned to the majors. Jimenez, a left fielder and pinch-hitter had never played much. He appeared in all of six games for the Cubs.

Hartenstein spent the whole season with the Pirates, appearing in 56 games — all in relief, 25 of them closing. He was 5-4 with a 3.95 ERA. It was a decent season, but in 1970, things took a turn for the worse. “I threw sidearm basically. I had a sinker from there that was my bread and butter. When I got to spring training in ’70, Don Osborn was the pitching coach. They wanted me to start throwing overhand. I could do that, but I did not feel effective. I had a bad spring and things just didn’t work out. I said, ‘I’ll try this overhand stuff, but if it doesn’t work out, you’ve got to give me a chance to get my stuff back.’ Let’s just say that year, I had a bad career, including Boston.”

Hartenstein’s 1970 season saw him work for three different teams. He began with the Pirates, but they had decided to use Dave Giusti as their closer and distribute relief work among an array of other pitchers. He was being used less than several of the others and in mid-June, the team put him on waivers. He was claimed by the St. Louis Cardinals and left Pittsburgh on June 22 with 17 appearances, a 1-1 record (with just one save) and a 4.56 ERA.

He worked 13 1/3 innings in six games for St. Louis. He had neither a win nor a loss, nor a save, but a discouraging 8.78 ERA. The Cardinals released him on July 8 to make room for Nelson Briles.17 A free agent, he attracted a number of offers but selected the Boston Red Sox; they worked out some kind of deal and on July 14 he was signed by the Red Sox. He worked four innings for the Louisville Colonels in three games, and then was brought to Boston. He said he was glad to be coming to the American League, because as a sinker ball pitcher, he induced a lot of grounders — and too many of them skipped through the infield on the National League fields with Astro Turf.18

Hartenstein was 0-3 for the Red Sox, working 19 innings in 17 games. His ERA was a disappointing 8.05. On September 10, the Red Sox acquired Bob Bolin, and assigned Hartenstein’s contract to Louisville.

There was even a major-league fourth team with which Hartenstein was contracted in 1970, if only for a number of hours. On December 31, his contract was sold to the Chicago White Sox.

For the next six years, Hartenstein pitched in the AAA Pacific Coast League. In 1971 and 1972, he worked for the Tucson Toros. He might not have worked at all, as he had been cut by the White Sox for economic reasons in early 1972 (while the players were on strike.) White Sox GM Roland Hemond talked the Tucson owners into signing him directly. He was 5-6 (3.60), in 49 appearances, and then 7-5 with an even 3.00 ERA in 74 games. The success in his second year, he said, was due to manager Larry Sherry — “the only manager I ever had who used me as I thought I should be used.”19

In February 1973, he was invited to camp by the White Sox but even before spring training began was traded to the San Francisco Giants. He spent ’73 and ’74 with the Phoenix Giants — not getting as much work (43 games and then 41), with ERAs of 4.03 and 4.88.

After spring training 1975, he was unconditionally released by the Giants. It took a while to find a place to sign on, but he signed directly with the Hawaii Islanders (a San Diego Padres affiliate) on May 23. He had two good years there. In 1975 he worked long relief — 76 innings in 27 games, with a 2.96 ERA and a record of 6-2. In 1976 he was 11-5 (3.19) with 96 innings in 39 games.

Those couple of years were good enough to propel him back to the big leagues. On November 5, 1976, his contract was purchased by the Toronto Blue Jays. It was a difficult year for him in 1977, but it worked out nicely in the end. He was in the bullpen for Opening Day, the first game the Blue Jays played at Exhibition Stadium. He worked in five April games and two in May, but his thumb was fractured on May 14 by a Rod Carew line drive that hit him hard. “I looked down and that last digit was looking at me,” he recalled. “The good news was that Roy Howell was playing third base and he picked the ball up and threw Carew out.”20 So Hartenstein earned an assist on the play.

He was 0-1 at the time, with a 5.40 ERA. It took him six weeks to heal. He helped the team out during some of his down time, working as an advance scout. He returned to the ball club on July 1, and appeared in six more games that month; they were his last six games as a pitcher. He lost another game, becoming 0-2, and closed the year with an overall 6.59 ERA. Manager Roy Hartsfield having added him to the staff in 1977 gave him enough service time to be able to qualify for a major-league pension.

He didn’t pitch at all in August but on September 2, the Blue Jays issued a press release announcing that he had been named their minor-league pitching instructor. He was to report to their Florida Instructional League team (tongue in cheek, Hartenstein called it the “constructional league”) and then work out of their spring training complex in Dunedin, Florida, working as a roving instructor throughout the year. The press release said he had unofficially assisted the Jays as an instructor during the 1977 season. He was said to have developed a close working relationship with Jays manager Roy Hartsfield and major-league pitching coach Bob Miller.21

In preparing for his new assignment, Hartenstein shared some words of wisdom that Miller had given him: “The first thing that Bob told me was to start putting on some weight. I worked hard it at and I think it has paid off. The fans tell the players from the coaches by their bellies.”22 He added, “Bob told me to start out with the basics, for instance, you need a good stop-watch so everyone can see you constantly checking it, seeing how long it takes each pitcher to move his moves, etc. The most important thing Bob told me is that, a couple of weeks before training camp begins you have to practice carrying around a clipboard. You have to learn to strike certain poses with this clipboard. There’s the studying look, when you stand with your eyes on the folder. When the brass is looking you make sure you’re always writing. That’s how they know you’re working. Another trick is to always have the first page on the board all filled up with writing of any kind. It really doesn’t matter if the writing has anything to do with baseball, just so the page is full. Even if you have to write large or skip around a lot.” Clearly Hartenstein was well-prepared for the next phase of his baseball career.

He served with the Blue Jays as Minor League Pitching Instructor from September 1977 through the 1978 season, then was signed in November 1978 as Major League Pitching Coach for the Cleveland Indians.23 The Jays and Indians had shared a team in the instructional league and Gabe Paul and Cleveland GM Phil Seghi had seen him work. Seghi said, “He’s the kind of pitcher who had to work hard to get by. He wasn’t an overpowering pitcher, so he had to learn how to get the hitters out. Those kind of fellows make good coaches. Fellows like Wes Stock and Lee Stange are excellent teachers even though they didn’t have great records themselves.”24

Hartenstein said he had been totally surprised to get the job offer, but he said he already had a philosophy: “I watch a young pitcher and then pick out what I consider his least problem and tell him about it. He works on it for a while and decides maybe this old guy knows what he’s talking about. Then he starts listening and becomes receptive to new ideas.”25

He worked the 1979 season for the Indians. Dave Duncan was on the coaching staff that year, too. The team finished 81-80, with Dave Garcia replacing manager Jeff Torborg in midseason. Hartenstein had been a Torborg hire; Garcia hired Dave Duncan as his pitching coach in 1980. “Dave and I have remained close over all these years,” Hartenstein said. “I always tell him, ‘Hey, Dunc. You owe me big time!’”26

Hartenstein worked as a minor-league pitching coach over the next seven seasons in the Padres, Pirates, and White Sox organizations. The Padres placed him in Hawaii, a not-disagreeable assignment.

In 1987, 1988, and 1989, Hartenstein was pitching coach for manager Tom Trebelhorn and the Milwaukee Brewers. The Brewers were in Toronto on June 5, and played in the first-ever major-league game at SkyDome (and won, 5-3). Thus Hartenstein earned the distinction of being in uniform for the first games at both Exhibition Stadium and SkyDome.

Hartenstein then became an advance scout for the California Angels, working in that capacity for a couple of years, and later serving in part-time scouting roles for the Twins and the Oakland A’s before retiring to life in Austin in 1995. It was time to come home and enjoy his grandchildren.

He had worked during the offseasons as a real estate salesman. Chuck and Joyce had two sons, Chris and Greg. Married for 57 years at the time of the May 2018 interview, he and his wife joked that it was 157 years. Chris Hartenstein became a CPA, and developed his own business working now, Joyce Hartenstein explained, as a financial advisor to other accountants. Greg, Chuck said, “is the mechanical engineer in the family, He’d had several jobs with companies I can’t even pronounce. He’s been like a project engineer. Both are very successful in their own fields. Both of them married good and we have five granddaughters. No grandsons, but five granddaughters.”

In 2015, he told interviewer Kevin Glew, “Physically I’m deteriorating, but my mind is still as dull as ever. I’m just having a ball sitting here and drinking Budweiser and being around my family.”27

Chuck Hartenstein died in Austin, Texas on October 2, 2021.

Last revised: February 21, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Hartenstein’s player questionnaire and player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 Kevin Glew, https://cooperstownersincanada.com/2015/10/06/ex-blue-jays-whatever-happened-to-chuck-hartenstein/

2 Author interview with Chuck Hartenstein on May 28, 2018. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations from him come from this interview.

3 Kevin Grew.

4 James Enright, “Longhorn Chuck Choice Steer in Cub Bullpen,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1967: 22. In 2018, Hartenstein elaborated: “Bibb Falk invited me and my mom to have dinner and look at the campus. We never signed anything. At the conclusion of the dinner, he simply asked, ‘Well, are you coming here or not?’ I asked, ‘Coach, are you talking about a full scholarship for four years?’ He said, ‘Yes. I’ve got one condition, though. I want you to stay with me for four years.’ I said, ‘OK, where do I sign?’ He said, ‘Sign? No, I don’t do that. I’ll shake hands with you. You shake hands with me and we’ve got a deal.’ Because of that handshake, for the rest of my life, if I give you a handshake, that’s the way it will be. I don’t need lawyers. I don’t need signed things. He taught me that. I abided by it, and that’s the way we are now.”

5 Ibid.

6 Per Chicago Cubs player records reviewed by SABR’s Scouts Committee on March 27, 2003.

7 Jerome Holtzman.

8 Author interview with Chuck Hartenstein on May 30, 2018.

9 Edward Prell, Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1967: C1.

10 Jerome Holtzman, “Cubs’ Twiggy Bends Batters Around Finger,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1967: 8. Hartenstein is listed in a number of databases at 165 pounds, but contemporary sources in 1967 all pegged his weight at 150.

11 “Cubs’ Hartenstein Proud Of His Twiggy Nickname,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1967: 10.

12 Bill Christine, “Twiggy Tag OK With Hartenstein,” Pittsburgh Press, March 20, 1969.

13 James Enright.

14 Jerome Holtzman.

15 Richard Dozer, “Cubs Trade Lou Johnson, Get Willie Smith,” Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1968: C1.

16 Author interview with Chuck Hartenstein.

17 “Redbird Chirps,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1970: 18.

18 Neil Singelais, ‘Hartenstein Glad to Get Away from Astro Turf,” Boston Globe, July 25,1970: 17.

19 Regis McAuley, “Weary-Armed Hartenstein Paying Off Debts in Tucson,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1972: 37.

20 Kevin Grew.

21 News release, Toronto Blue Jays, September 2, 1977.

22 Blue Jays Booster Club Newsletter, April 1978.

23 Toronto Blue Jays press release, November 6, 1978. “We’re very happy for Chuck,” said Blue Jays VP of Baseball Operations Pat Gillick. “This is a step up. He is a hard worker and did an excellent job.”

24 Undated Cleveland Indians press release from Tucson, Arizona (spring 1978).

25 Ibid.

26 Author interview with Chuck Hartenstein on May 30, 2018.

27 Kevin Glew.

Full Name

Charles Oscar Hartenstein

Born

May 26, 1942 at Seguin, TX (USA)

Died

October 2, 2021 at Austin, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.