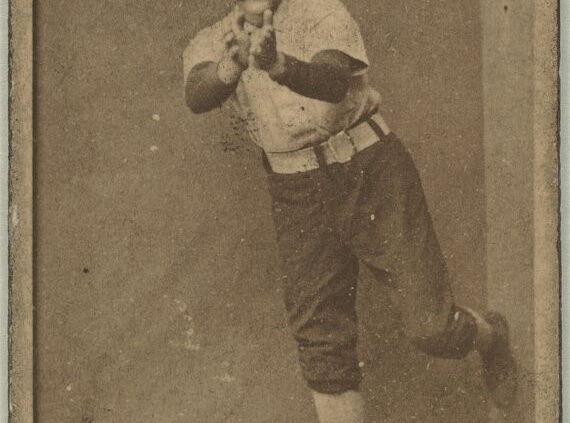

Cliff Carroll

During the 1892 season while playing for St. Louis, Cliff Carroll had the misfortune of being fined by the club when a ball inadvertently rolled into his pocket. The incident, which occurred in the sixth inning on August 17 of that season, was his major claim to fame, although in his time he was a fair hitter, fielder, and stolen–base threat and had, in 1890, come back from exile to help lead the Chicago Colts to a second–place finish.

During the 1892 season while playing for St. Louis, Cliff Carroll had the misfortune of being fined by the club when a ball inadvertently rolled into his pocket. The incident, which occurred in the sixth inning on August 17 of that season, was his major claim to fame, although in his time he was a fair hitter, fielder, and stolen–base threat and had, in 1890, come back from exile to help lead the Chicago Colts to a second–place finish.

Hugh Fullerton, in American Magazine, reported on the errant–ball incident. In a game at St. Louis, Carroll charged a ball hit to the outfield by Brooklyn’s Darby O’Brien, seeking to field it on the first bounce. The ball took a bad bounce and hit Carroll in the chest. He grabbed the ball and inadvertently shoved it into the handkerchief pocket on the front of his uniform shirt. The runner, noticing this, just kept on running and advanced to second base. At this point, Carroll ran toward the infield and fielder and runner raced toward third base. Try as he would, Carroll couldn’t dislodge the ball and the runner scored. Team owner Chris Von der Ahe had pockets removed from his team’s uniforms, and the rest of the National League followed suit.1

The game was not particularly close, with Brooklyn winning 11–3 and the Browns making 12 errors. Both George Gore and Bill Moran had committed errors early in the game and before Carroll’s muff the score was already 6–0. The St. Louis Post Dispatch wrote, “Yesterday’s exhibition baffles description. If the Browns had the jaundice, they couldn’t have played yellower ball. It was an absolute burlesque on the game. The spectators jeered the players and managed to extract fun out of their attempts at playing.” After the game, Von der Ahe fined Carroll and Moran $50 each for “general indifference and rotten playing.”2 At season’s end, Carroll was made available in trade to Boston.

Carroll played in the National League for parts of 11 seasons between 1882 and 1893. Although not known as a power hitter, in 1890 and 1891 with the Chicago Colts he had seven home runs each year and finished in the top 10 in the league. He also has the rare distinction of homering at the same ballpark in the minors and majors. While with Providence in 1885, he hit a home run at Buffalo’s Olympic Park on October 7 off Pete Conway in the opener of the last series at that venue. Of his 31 major–league homers, that was his only blast at Olympic Park. Carroll’s career was temporarily on the downturn in 1888 and he wound up in the minor leagues, playing with Buffalo in the International Association. On June 23, 1888, he homered at Olympic Park in a 10–2 shellacking of Albany. Each of his two minor–league homers that season was at Olympic Park. He thus became the fifth player in Organized Baseball to homer at the same ballpark in the majors and minors.

Samuel Clifford Carroll was born on October 15, 1859, in Clay Grove, Iowa. He grew up in Bloomington, Illinois. His parents, John M. and L. Marie Carroll, had five children. Three sons came along before Cliff and his twin sister, Katy, were born. It was in 1867 that the family relocated to Bloomington.

John M. Carroll, who had been born in Baltimore on April 12, 1821, was a pillar of the community in Bloomington, operating a grocery store. But he suffered financial losses during the banking crisis of the early 1870s. He spent the last decades of his life in darkness as he went blind on December 25, 1876. He died on July 6, 1909, at the age of 88. Cliff’s mother, who survived her husband, was born in Butler County, Ohio, on November 5, 1823. She was called Maria.3 She lived to the ripe old age of 95, dying on November 18, 1918.

By 1877, Cliff had established his baseball credentials to the point where he became a member of Bloomington’s semipro club. The New York Clipper tells us, “The members consider the nine the strongest they have ever had and would be pleased to hear from all Eastern clubs going West. They say they have splendid inclosed grounds and promise good terms.” Among the team’s directors was pitcher Charles Radbourn.4 In 1878, he entered the professional ranks and made his way to Oakland, California, where his team won the California State championship. He continued to play in California through 1880, when he was suspended on one occasion for overdrawing his account with the team by $60.5 He then made his way to the Nevada silver mines, but an old friend from his Bloomington days brought him to the attention of Providence Grays manager Harry Wright.

Carroll made his major–league debut with Providence in August 1882. He was the second player from Bloomington to be signed by Providence. Radbourn, his old teammate, had also become a major leaguer. The right fielder got into 10 games at the end of the season. Although he went only 5–for–41, he received plaudits for his fielding. After his first League game on August 3 against Cleveland, it was said that “Cliff Carroll, the new right fielder, showed up famously in the field.”6 An article in his hometown Bloomington newspaper noted, “(Carroll) has played his first three games without making an error, but for some reason, he does not loom up in his batting as of old.”7 In one of those games, on August 17, Carroll was in the outfield alongside his old pal Radbourn. Monte Ward was pitching and hurled an 18–inning shutout. Radbourn provided the only offense his team would need with an 18th–inning home run. It was the first career homer for Radbourn, who went on to hit nine homers to go along with his 309 wins on the mound. The win kept the Providence lead at three games. They took that lead into September but lost it when they were swept by Chicago in a three–game series. The Grays wound up finishing in second place. Carroll did not make an error in the field until October 11 in a postseason exhibition game against first–place Chicago.8

Carroll first gained unpleasant notoriety in 1883 while playing with Providence. During practice before the game, he picked up a hose and sprayed water onto a spectator named James Murphy. Mr. Murphy was not amused by this, went home, and came back carrying a gun. He took a shot at Carroll and missed, but struck Carroll’s teammate Joe Mulvey.9 Playing in 58 of his team’s 98 games (he missed some time in May and June with a sprained ankle), Carroll batted .265 as the Grays finished in third place with a 58–40 record.

In 1884, Providence won the National League pennant with an 84–28 record and Carroll played in 113 games batting .261 with 23 extra–base hits and 54 RBIs. After the season, Providence accepted a challenge from the American Association champion Metropolitans of New York. The three–game championship was held at the Polo Grounds. In the first game, Carroll reached first base after being hit by a pitch, and came around to score as Providence won 6–0. He went 1–for–10 with two runs scored and an RBI in the three games. Radbourn, who had won 59 games during the regular season, was the only pitcher Providence needed. He pitched every inning and won each game as Providence swept the Mets for the championship.

It is for one deed during that 1884 season that Carroll is also remembered. Per teammate Arthur Irwin, Providence was playing at Boston. In the fifth inning of the game, Carroll reportedly came up with the idea of bunting the ball and laid down the first bunt. Of course, since it was the first (per Irvin), it had yet to be named. In the Boston Herald, per Irvin, the reporter said that Carroll “punted” the ball. Eventually, of course, “punt” became “bunt.”10 By the time the teams played on August 9, with Providence winning 1–0, the term “bunt” was being used. In the game of that date Carroll laid down a bunt in the eighth inning.11 Actually the bunt had been part of the game since the 1860s and into the early years of the National Association, with Dickey Pearce and Tommy Barlow credited for its invention. However, the bunt had been not utilized for a decade when Carroll and Irwin brought it back into the game.12

The 1885 season was Carroll’s last with Providence. He batted .232 while playing in 104 of his team’s 110 games as the Grays finished in fourth place, Chicago and New York running away from the pack. Providence, with its 53–57 record, finished 33 games out of first place.

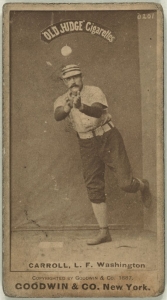

Carroll signed on with Washington in 1886 and spent two years in the nation’s capital. But they were not without controversy. During the 1886 season, Carroll was fined $100, a hefty sum in those days, for his objections to team management using amateur pitchers.13 He balked at re–signing for the following season unless the fine was rescinded by team President Walter Hewitt. Hewitt agreed, and cut a check to Carroll. However, before Carroll could cash the check, Hewitt stopped payment. This only made things worse. At the winter meetings, other owners prevailed on Hewitt to remedy the situation and he did.14 In Carroll’s first year with Washington, his batting average dropped to .229, but he did finish in the top 10 in stolen bases with 31 for a team that finished last with a 28–92 record.

According to an inaccurate accounting in Fred Lieb’s The Pittsburgh Pirates, in 1887 Carroll was with the Pittsburgh Alleghenies, and was positioned at first base for a few games after first baseman Alex McKinnon became ill and died. Carroll was described by Lieb as a “good hit, no field outfielder.” However, Carroll spent the entire 1887 season with Washington, batting .248 while appearing in 103 of his team’s 126 games. But he was no longer the quality player he had been in his Providence days. The author may have confused Cliff Carroll with Fred Carroll who in 1887 batted .328 with Pittsburgh and made 62 errors, including 14 in 17 games at first base. He also made 27 as a catcher and 21 as an outfielder.

At the end of the 1887 season, in which Carroll lifted his batting average to .248 and had a career–high 40 stolen bases, he was released by Washington after the team finished the season in seventh place with a 46–76 record. By that time, “for lack of care of himself, he became almost valueless to the club, and was released.”15 The release was motivated by Carroll’s drinking. While in Washington he owned a saloon for a time, and was his own best customer. The team thought Carroll was attending to business too closely, staying up late at night, and therefore released him.16 He moved on to Pittsburgh in May 1888, as a replacement for John Coleman, who was ill.17 He was with Pittsburgh for less than a month and got into only five games before overstaying his welcome. Carroll was released on June 4, 1888. His once highly regarded fielding skills had eroded. In his five games, all in the outfield, he made three errors in nine chances.

In 1888, after six seasons in the National League, Carroll went back to the minor leagues, playing with Buffalo in the International Association. Although he batted .282 with 22 extra–base hits and 27 stolen bases, his talents were no longer in demand. He spent the 1889 season out of baseball entirely, getting married to Addella Wood of Bloomington and tending to his farm.18 A daughter, Bernice, came along on December 28, 1889. She was their only child. According to data in the 1920 Federal census, she married Thomas Armentrout, and they had four children.

At the urging of Old Hoss Radbourn in 1890, several teams in the newly formed Players League contacted Carroll about returning to baseball, but it was Cap Anson of the National League’s Chicago Colts who signed Carroll to play for his team.19 Carroll had accompanied Anson and the team in a world tour after the 1888 season.20 In 1890, he signed with Anson’s Colts and had the two most productive seasons of his career. Early in the 1890 season, it was reported that “Cliff Carroll, the fleet–footed left–fielder of the Chicago club, is under a pledge not to touch intoxicating liquors this season. This was his greatest failing as a ballplayer, and caused his retirement for a time from the diamond. But for the Brotherhood (as the Players League was also known), he would probably have never been given an opportunity to return to the profession. His brief retirement seems to have done him much good as he is playing splendid ball for the Chicagos. He is one of the finest fielders in the country, a good batter and a clever base–runner.”21

Chicago, then called the White Stockings, had finished in third place in 1889 with a 67–65 record, 19 games behind the pennant– winning New York Giants. There were numerous changes in 1890. The team’s name was changed to Colts. More importantly, there was a team overhaul. Anson brought on Carroll along with young pitchers Pat Luby (21) and Ed Stein (20). He also added second baseman Bob Glenalvin, shortstop Jimmy Cooney, and slugging outfielder Walt Wilmot. The changes worked.

In 1890, the Colts finished in second place with an 83–53 record. The team did not lack for offense, scoring 10 or more runs on 26 occasions. They went 23–6 in September but were unable to catch Brooklyn, finishing 6½ games behind the league champions. At the insistence of Anson, Carroll gave up switch–hitting and hit exclusively from the left side.22 He batted a career–high .285 with seven home runs (fifth best in the league) and 65 RBIs. He stole 34 bases. On his own team, only Anson (.312) posted a higher batting average. Carroll had a team–leading 134 runs scored, second in the league, and he finished fourth in the league with 166 base hits. He led the league with 137 singles. His 215 total bases were ninth best in the league. He also flashed his glove in 1890, finishing fourth in outfield assists with 28.

Carroll also got on pitchers’ nerves during games by switching sides of the plate while the pitcher was warming up. The rule restricting this practice did not go into effect until 1914.23

After returning to the major leagues in 1890 and enjoying his best season, Carroll played in the National League through 1893, finishing his career with the Boston Beaneaters, who won the National League pennant in 1893.

In 1891, he once again put up good numbers with the Colts, although some were not as good as those in 1890. His power numbers were on the ascendant as his extra–base hits increased from 29 to 35 and his 80 RBIs were second best on the team. However, his batting average slipped to .256. Carroll was 31 years old and did not fit into Anson’s plans, as Carroll and Anson grew further apart as the season progressed.

In 1892, Carroll signed with the St. Louis Browns. His season was going well and he was on his way to a .273 batting average when his fielding mishap on August 17 placed him on the outs with team ownership.

Boston manager Frank Selee traded for Carroll before the 1893 season, sending Joe Quinn to St. Louis in exchange. He played the outfield for Boston as Bobby Lowe was moved to second base. Although Carroll’s overall statistics for the season were not good, (he batted a disappointing .224, the worst average in the league of any hitter with 400 or more at–bats24), he was a key factor in his team’s success. The 33–year–old patrolled left field in 120 of his team’s 131 games. One of Old Cliff’s best performances came on June 14, in the field and at the plate. Boston was playing St. Louis and in the second inning Carroll, playing in left field, made a spectacular catch. The Boston Journal mentioned:

“The pleasing feature of the game was ‘Cliff’ Carroll’s rejuvenation. To him must be given the glory of making the best catch seen on the grounds this season. Lew] Whistler hit the ball to the farthest corner of left field, but Carroll caught it while on the dead run toward the seats, though he fell after his great effort.”25

Carroll’s day was not complete. The Beaneaters trailed by two runs as they came to bat in the ninth inning. With none out and Billy Nash and Tommy Tucker on base, Carroll came up to bat. The Boston Globe tells us that:

“Carroll now had a chance to pay back an old grudge he owed Mr. Von der Ahe. First he fouled one [pitch] trying to sacrifice. Turning to Hugh] Duffy, he nodded as much to say, ‘Will I cut loose?’ Duff answered, ‘As you like.’ The next instant, the ball was going on a line to center over (Steve) Brodie’s head, two runs coming in and the score tied.” After the double, Carroll advanced to third on a wild pitch and scored, with two outs, on a single by Tommy McCarthy.26 Boston had an 11–10 win and remained tied for first place. The Beaneaters went on to win the pennant by five games. Carroll did not play in the major leagues after 1893. For his career, he batted .251 in 991 games, with 203 extra–base hits and 423 RBIs.

The hit–by–pitch statistic was not kept in the National League until 1887, but records indicate that Carroll was quite proficient at taking one for the team. On three occasions between 1887 and 1892, he finished in the top five in the league. In 1891 Sporting Life noted, “Cliff Carroll is winning games for Anson by letting pitched balls hit him. Cliff is too old and tough to feel anything short of a rifle ball.”27 In August 1897, Carroll remembered a few things while speaking with Sporting Life. “I think I have one distinction that no player of the present time is anxious to earn. I have been hit oftener by Amos Rusie than any other man. And even to earn a base, it’s no joke to be hit by Rusie. When another pitcher hits a man, the man rubs himself; when Rusie hits anyone, the man usually goes to bed.”28 In addition to his farming interests, Carroll also operated a meat market in Bloomington, but sold the business prior to the 1892 baseball season.

In 1894, Carroll finished his career with Detroit of the Western League.29

After his playing days, Carroll farmed in Hoopeston, Illinois, before relocating to Linn, Oregon, in 1910, where he tended to a 280–acre fruit farm. While in Hoopeston, he was, according to an account in Sporting Life, “Regent and Ruling Monarch” and manager of a ballclub in the area.30

Carroll died in Portland, Oregon, on June 12, 1923, and is buried at Lincoln Memorial Park. He was survived by his wife and daughter. Largely forgotten to the baseball world at the time of his passing, he was eulogized in print. The following was printed in the Oregonian:

“Carroll was the most wonderful fielder whoever trod a diamond. He had Ty Cobb faded as a base stealer and run getter. He and Charley Radbourne [sic] were inseparable. Carroll was almost as much the vogue as a fielder as Radbourne was as a pitcher. He will be remembered by old timers as one who helped to give the game of baseball impetus in its infancy and his feats of that long–passed day imparted much of the glamour that has since made baseball the most popular sport in America.”31

And the following (perhaps a bit overstating the case) appeared in his hometown Bloomington Daily Pantagraph.

“He owned a large collection of souvenirs and mementoes. Carroll, in addition to being a wonderful hitter and fielder ranked with the fastest men on the bases. One remembrance consisted of a pin representing a foot with two miniature wings to represent fleetness. The foot is of gold and the wings were set with diamonds. He was the greatest of his day and generation.”32

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball–Reference.com, Ancestry.com, and:

Balinger, Ed F. “Cliff Carroll Claimed by Death: Was Pirate Star of Bygone Days,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 22, 1923: 13.

Notes

1 Hugh S. Fullerton, “Freak Plays That Decide Baseball Championships,” American Magazine, May 1912: 118, reprinted in Warren County (Illinois) Democrat, May 23, 1912: 20.

2 “Comedy of Errors: The Browns Give a Fearful Exhibition of Poor Ball Playing,” St. Louis Post–Dispatch, August 18, 1892: 12.

3 “John Carroll Obituary,” Weekly Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), July 9, 1909: 6.

4 “Shortstops,” New York Clipper, May 26, 1877: 67.

5 “The Game in California,” New York Clipper, July 10, 1880: 125.

6 “Sic Semper M’Ginnis,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, August 4, 1882: 8.

7 “Amusements,” Bloomington Daily Leader, August 12, 1882.

8 “Another Defeat for the Chicago Nine at Providence,” Boston Herald, October 12, 1882: 3.

9 Don Doxsie, Iowa Greats: Sixteen Major Leaguers Who Were in the Game for Life (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 2015), 182–183.

10 Frank G. Menke, “Cliff Carroll First Player to Bunt Ball: Member of Providence Grays, in 1884, Paralyses Opponents and Fans with Unexpected Action,” Idaho Statesman (Boise), February 19, 1921: 6.

11 “T’was a Good Game: And Providence Won It in the 11th Inning,” Boston Herald, August 10, 1884: 2.

12 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Rowman and Littlefield, 2010), 53–55.

13 “From the Capitol: Harsh Treatment of Players – Cliff Carroll’s Suspension – Barr’s Release, etc.,” Sporting Life, August 11, 1886: 1.

14 “The Washington Club,” The Sporting News, December 31, 1886: 1.

15 “They Play With Anson,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1890: 28.

16 “Diamond Notes,” Cleveland Leader and Herald, May 10, 1888: 3.

17 “On Tour With the Bostons: Some Observations of a Clipper Correspondent on Absurdities in the Rules,” New York Clipper, May 19, 1888: 157.

18 “Player Carroll Married,” Daily Inter–Ocean (Chicago), February 28, 1889: 2.

19 “Carroll to Play Again,” Kalamazoo Gazette, February 9, 1890: 8.

20 Obituary, Oregonian (Portland), June 25, 1923: 11.

21 “Sporting Gossip,” Anaconda (Montana) Standard. May 8, 1890: 6 (originally appeared in Cincinnati Commercial–Gazette).

22 “Winter Ball Talk,” Kansas State Journal (Topeka), March 7, 1890: 7.

23 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Baseball (New York: Donald Fine Books, 1997), 340.

24 Nemec, 499.

25 “A Close Call: Boston Won the Game Because the Umpire Did Not See a Trick by Glasscock,” Boston Journal, June 15, 1893: 3.

26 “Pretty Finish – Boston Makes a Spurt in the Ninth Inning,” Boston Globe, June 15, 1893: 9.

27 “News, Gossip, and Comment,” Sporting Life, August 15, 1891: 2.

28 W.A. Phelon Jr., “Chicago Gleanings,” Sporting Life, August 28, 1897: 11.

29 George V. Toohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club (Boston: M.F. Quinn, 1897), 226–227.

30 W.A. Phelon Jr. “Chicago Gleanings,” Sporting Life, February 8, 1896: 5.

31 James H. McCool, “Blue Mountain League to Close Down for Harvest,” Oregonian, June 25, 1923: 11.

32 “‘Cliff’ Carroll,” Obituary in Bloomington (Illinois) Daily Pantagraph, June 18, 1923: 10.

Full Name

Samuel Clifford Carroll

Born

October 18, 1859 at Clay Grove, IA (USA)

Died

June 12, 1923 at Portland, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.