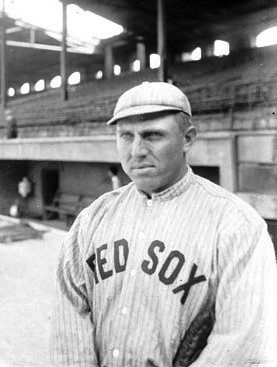

Clyde Engle

Every baseball player whose career has been eclipsed by a single bad play during a World Series – Bill Buckner, Mickey Owen, and Fred Snodgrass – benefits from the redeeming quality of infamy: They are remembered. And, in most cases, they have also secured a place in baseball history, a much smaller berth, for the beneficiaries of their blunders. It was Mookie Wilson’s groundball that went through Bill Buckner’s legs in 1986. Tommy Henrich is the one who got a free ride on Mickey Owen’s dropped third strike in the 1941 series. And it was Hack Engle’s high fly ball that Fred Snodgrass let drop in right field in the deciding game of the 1912 World Series.

Every baseball player whose career has been eclipsed by a single bad play during a World Series – Bill Buckner, Mickey Owen, and Fred Snodgrass – benefits from the redeeming quality of infamy: They are remembered. And, in most cases, they have also secured a place in baseball history, a much smaller berth, for the beneficiaries of their blunders. It was Mookie Wilson’s groundball that went through Bill Buckner’s legs in 1986. Tommy Henrich is the one who got a free ride on Mickey Owen’s dropped third strike in the 1941 series. And it was Hack Engle’s high fly ball that Fred Snodgrass let drop in right field in the deciding game of the 1912 World Series.

Born on March 19, 1884, in Dayton, Ohio, Arthur Clyde Engle was the youngest of three boys born to Isaac and Lina (Bitzer) Engle. Isaac was the chief engineer of the plant that powered the Dayton City Railway’s electric trolleys. After gaining local baseball acclaim in and around his hometown, Clyde, as he was known to friends and census-takers throughout his life, entered the professional ranks in 1903 as a pitcher with the Nashville Volunteers of the two-year-old Southern Association.

In 1904, he played 15 undistinguished games in the outfield with the Dayton Veterans of the Class B Central League before signing with the Augusta (Georgia) Tourists of the South Atlantic League as a center fielder for the rest of that year. In Augusta, he joined several teammates who would go on to the major leagues and their own attachments to fame and infamy, including Eddie Cicotte of the 1919 Black Sox Scandal and the irascible Ty Cobb.

During the 1905 season, Engle moved from the Augusta outfield to second base and, with a.265 average, became one of the top batters on the team. In fact, he might have made it to the majors at the end of that year if it hadn’t been for Cobb. The Tigers had been trying to choose between Cobb and Engle and they were leaning toward Engle because Tigers manager Bill Armour thought Cobb had “a screw loose.” But Engle’s hitting waned in the late summer heat while Cobb’s soared and, on top of that, the rest of the team was, not surprisingly, not enjoying Cobb’s pugnacious temperament. And so, in August 1905, Cobb was sent to the majors, and the next season Engle moved to Newark of the Eastern League.

Engle made progress in his three seasons with the Newark Sailors. He gained experience, playing 125 to 141 games each season, and lifted his batting average from .216 in 1906 to .259 in 1908. Near the end of that run, Engle caught the eye of New York Highlanders manager George Stallings and was signed for the 1909 season. Although he had spent most of 1908 in Newark at third base and shortstop, he often told reporters he didn’t like the infield. He was happy when playing left and center fields during spring training in Macon, Georgia. But Stallings tried him in the infield – at second and third as well, with good results. Engle had earned the opportunity to play major-league ball.

In the Highlanders’ season opener in Washington, Engle started his first official major-league game where he preferred to play: left field. According to the April 13, 1909, New York Times, 15,000 fans witnessed Engle in top fielding form:

“The fielding feature of the game was a remarkable one-handed catch by Left Fielder Engle on a long fly from Street’s bat in the third inning. There were three men on the bases and only one out at the time. Engle ran to the edge of the crowd in left, and, as the ball was sailing over his head, jumped and grabbed the ball in his ungloved hand. As Engle disappeared into the mixture of arms and legs he held to the ball.”

Engle’s inaugural performance with a fly ball was not the only foreshadowing of his later claim to fame. He appeared in 135 games, playing left and center fields, and his .278 average was third best on the Highlanders. The right-handed batter drove in 71 runs, tops on the team. At under 5-feet-10 and weighing 190 pounds, he even earned the nickname Hack for his resemblance to the stocky strongman and professional wrestler Georg Hackenschmidt. But in one of his last appearances of the season, Engle made an error of nearly Snodgrassian proportions.

“Engle’s Muff Dazes Hilltop Fandom” proclaimed the headline in the October 1, 1909, New York Times. There were two men out and none on base in the top of the ninth, with the Yankees leading the visiting St. Louis Browns, 4-2. Second baseman Hobe Ferris popped an easy fly ball. Engle was so sure of catching it that he added some flourishes to his performance—what the Times called a “Hogarthian curve.” Hilarity ensued:

“Hack’s feeling of sureness was shared by his comrades and even most of his opponents. Almost all the players on the diamond and the benches began their dash for clubhouse before the ball, high in the air, quivered in its turn for the descent. Chase sped so swiftly toward his shower bath and street clothes that he was close to the clubhouse gate ere the ball came to earth. In addition, at least a tithe of the 1,000 spectators spraddled themselves across the diamond in the customary pursuit of the players. But, alas! The game was not at an end. No indeed! Down came the ball—down, down, shooting straight and true toward Engle’s upraised hands and then—why down, down, down it kept going, right between those hands, until it bounced on the waiting lawn. Engle was so dazed by his misplay he didn’t know what to do next.”

The Browns went on to tie the game, which was then called on account of darkness.

New York sold Engle’s contract to the Boston Red Sox early in 1910 season, on May 10. He was initially signed as a third baseman, but as he told one reporter, “I play wherever they put me and do the best I can.” That perspective served him well; over the next 4½ years with Boston, he played every position except pitcher and catcher. The trade put him on a ballclub that would win the pennant a couple of years later.

In 1910, Engle mostly split his time between third base and second base, although he also played seven games at shortstop and 18 games covering various outfield positions. He hit for a .264 average. He boosted that a bit in 1911, to .270.

The 1912 Red Sox had such a strong infield that Engle was relegated to a utility role and appeared in only 58 games, hitting .234. He was often used as a pinch-hitter and that is the role he played in the 1912 World Series against the New York Giants. In the sixth game, Engle stepped in for Buck O’ Brien and hit a double off future Hall of Famer Rube Marquard, driving in the Red Sox’ only runs in that loss. In the eighth and final game (there had been a tie game, and the teams were tied at three games each), Engle faced another future Hall of Fame inductee on the mound—the almost mythical Christy Mathewson. In the bottom of the 10th inning, with the Giants in the lead 2-1, Engle stepped up to home plate to bat for pitcher Joe Wood. Engle lofted a routine fly ball into the outfield and center-fielder Fred Snodgrass called for it, or, if you believe Snodgrass’s later account, was asked to get it by left-fielder Red Murray. Snodgrass caught the ball, but dropped it before throwing it to Murray to get it to the infield. Engle made it to second base and the “$30,000 muff” went down in history (the difference between the payout to the losers and the winners of the series was $29,514).

The mistake didn’t directly lose the game and, if Snodgrass had caught it, it would not have won the game either. In fact, Snodgrass made what all commentators considered an excellent running catch on the next batter, Harry Hooper. Engle moved to third on that play. Steve Yerkes walked. And the blame stuck, as another blunder occurred. First baseman Fred Merkle (already carrying the burden of a bad play in an important game), catcher Chief Myers, and Mathewson let a foul ball from Tris Speaker’s bat fall between them. Speaker then slammed a ball into right field to send Engle home with the tying run. Two batters later, a sacrifice fly by Larry Gardner allowed Yerkes to score the winning run. The world championship belonged to the Red Sox.

One wonders if Engle might have been readying himself for the second act of his baseball career—as a coach—while he toiled for Boston throughout 1912 and 1913. During Red Sox spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas, Engle was put in charge of the Yannigans, whipping the rookies and second-string players into shape. During the World Series, he was found coaching third base. His facility in this role did not go unnoticed. Legendary Boston Globe sportswriter and editor Tim Murnane wrote:

“I find that Engle is a fine student of the game. Last year he took a deep interest in the work of Harry Hooper, and convinced the great young player that a heavier bat than he was using would help his batting. In fact, Hooper’s remarkable improvement at the bat was a revelation to the members of the American League.”

In 1913, Engle’s fielding was just above average for American League first basemen that year, at .987, and he made the third most errors, at 17. But from a batting perspective, it was Engle’s best season in the majors; playing 133 games at first base, he batted.289 with 17 doubles, 12 triples, and two home runs in 143 games overall. Perhaps as a result of his success, Engle bargained hard for his 1914 contract. Throughout his career, Engle was one of the first players to sign his contract in the offseason; he was always among the first to show up at spring training. But in the winter before the 1914 season, rumors circulated that Engle might jump to the new Federal League. A bit of drama played out on February 12, 1914, in New York, according to the next day’s Boston Globe.

“Engle reached New York this afternoon at 4:30, on his way to a conference with Pres. Gilmore of the Federal League, but was met at the depot by Pres. J.J. Lannin of the Boston Red Sox and escorted to the Biltmore Hotel and, after a short conference, Clyde signed his contract and said he was delighted to be with the Red Sox once more.”

Engle was again assigned as first baseman. By late May, rumors were already circulating about the possible sale of Engle back to New York. In August, after just 59 appearances and one of the lowest batting averages of his career (.194), Engle was released by the Red Sox and joined the Buffalo team of the Federal League at third base. He raised his batting above .250 and rejoined Buffalo for the 1915 season, playing mostly in the outfield and ending the season at .261. At the end of the season, Engle considered a university coaching job, but decided to go another year with Buffalo. Unfortunately for him, the league folded before the 1916 season could begin and Engle was set adrift (although his contract was required to be paid in full).

The Cleveland Indians signed Engle, but he played just 11 games; he took advantage of the time and helped do some first-base coaching while there. This included a series of games where he was later accused of tipping off batters as to which pitch the Red Sox were throwing by reading the signals of his former teammates. After his short sojourn with Cleveland, Engle finished his season with the Topeka, Kansas, team of the Western League (Class A), taking on the team manager duties while batting .290 and playing third base. When Topeka left the Western League, Engle’s career in professional baseball ended.

During World War I, Engle joined the shipbuilding effort at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts. He played for the shipyard team while there. In 1919, he took over as baseball coach at the University of Vermont for a year and then joined his old Red Sox teammate Smoky Joe Wood at Yale. For the next 18 years, Engle coached the freshman squad at Yale while Wood coached the varsity.

Throughout his Yale years, Engle kept in touch with his friends in professional baseball, attending old timers games and doing some scouting work for Toronto and other teams. He died from a heart attack on December 26, 1939, at the age of 55 at Boston’s Lenox Hotel. He had been divorced from his wife, Natalie Miller, several years earlier and no children were listed in his death notices. His body was sent home to his brother in Dayton for burial.

When Snodgrass died 35 years after Engle, his obituary in the New York Times was headlined: “Fred Snodgrass, 86, Dead; Ball Player Muffed 1912 Fly.” Although the error featured prominently in Engle’s obituary, it was a gentler sub-head: “CLYDE ENGLE, 54; EX-YANKEE PLAYER; Baseball Coach of Freshmen Team at Yale Is Victim of a Heart Attack ALSO WITH THE RED SOX Gained Wide Notice in 1912 World Series for Hitting Fly Snodgrass Missed.”

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the text, the author consulted US Census, military draft, birth, marriage, and divorce records via Ancestry.com; statistical data from Baseball-Reference.com and Baseball-Almanac.com; and contemporaneous reports from the following publications: The Sporting News, Boston Journal, Kansas City Star, Hartford Courant, Augusta Chronicle, Grand Forks Herald, and Sporting Life. The anecdote about Cobb’s time with Engle in Augusta is from Al Stump’s Cobb: A Biography and The Detroit Tigers by Frederick Lieb.

Full Name

Arthur Clyde Engle

Born

March 19, 1884 at Dayton, OH (USA)

Died

December 26, 1939 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.