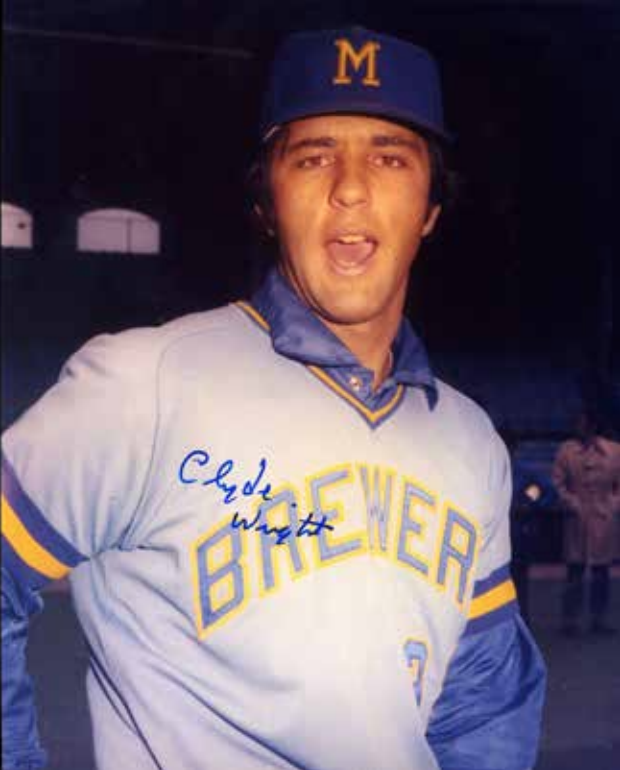

Clyde Wright

Jefferson City, Tennessee, is a small farm town at the western foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. Clyde Wright was born there on February 20, 1941. During the 1940s and ’50s, when he was a boy, life in Jefferson City revolved around family, friends, chores, and school. For Clyde, family meant mom, dad, his five brothers, and his sister. Living on a farm, there were always cows to milk, hogs to feed, fields to work, or neighbors to help, but the Wright boys usually found time to have a little fun: baseball, football, or fishing at either Cherokee or Douglas lakes. It was a world that rarely extended beyond Knoxville, 30 miles down “the four lane,” Route 11.1 Even college for Clyde was at the hometown school, Carson-Newman. This was the world that Clyde Wright knew growing up and the world that taught him his work ethic and fair-minded, easygoing outlook.

Jefferson City, Tennessee, is a small farm town at the western foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. Clyde Wright was born there on February 20, 1941. During the 1940s and ’50s, when he was a boy, life in Jefferson City revolved around family, friends, chores, and school. For Clyde, family meant mom, dad, his five brothers, and his sister. Living on a farm, there were always cows to milk, hogs to feed, fields to work, or neighbors to help, but the Wright boys usually found time to have a little fun: baseball, football, or fishing at either Cherokee or Douglas lakes. It was a world that rarely extended beyond Knoxville, 30 miles down “the four lane,” Route 11.1 Even college for Clyde was at the hometown school, Carson-Newman. This was the world that Clyde Wright knew growing up and the world that taught him his work ethic and fair-minded, easygoing outlook.

Wright’s ascent to the major leagues was swift. In June 1965 he was a senior at Carson-Newman College pitching his hometown college team to the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) championship. A year later he was on the mound for the California Angels pitching in his major-league debut against the Minnesota Twins. In both cases he won impressively. The NAIA championship game against the University of Nebraska-Omaha took 13 innings before Carson-Newman could scratch out a 3-2 win. In the game Wright struck out 22, a Carson-Newman record that, as of 2017, still stood. He was chosen the tournament’s most valuable player.

Selected by the California Angels in the sixth round of the 1965 draft, the major leagues’ first free-agent draft, Wright spent his summer pitching in Davenport, Iowa, for the Quad City Angels, an A-level team in the Midwest League. The young hurler proved to be one of the few bright spots on the team. Though Quad City finished 17 games beneath .500, Wright compiled an impressive 7-2 record with a 1.99 earned-run average. It was good enough to earn him a promotion the following season to the El Paso Sun Kings in the Double-A Texas League. Starting the season with eight consecutive wins, he quickly became the team’s ace. Then on June 10, he was called up to the Angels. Despite the call-up, that evening he went out and beat the Arkansas Travelers, 2-1, for his ninth victory.2 The next morning he was on a plane to Chicago to join his new team.

Five days after having beaten Arkansas, Wright was penciled in to start the first game of a doubleheader against Harmon Killebrew, Tony Oliva, and the rest of the reigning American League champion Minnesota Twins. His mound opponent, Jim Kaat, would chalk up 25 wins during the season.

A wiry 6-foot-1 180-pound southpaw, Wright as a collegian did it all. A right-handed batter though he threw left-handed, he was one of his college team’s leading hitters and a dominant pitcher who won 32 of the 37 college games he pitched.3 As a professional he was never an overpowering pitcher who racked up strikeouts. Instead he relied on precise control and stealth. His method was to move his pitches around, change speeds, and hit his spots. On the mound he considered the white part of home plate the hitter’s part. The black part was his part. His goal was to keep hitters off balance, outthink them. He preferred to get an out with one pitch instead of five or six. Later in the southpaw’s career Reggie Jackson maintained, “Clyde Wright is one of the best in baseball today. He knows how to pitch.”4 Others came to share Jackson’s opinion comparing him to Whitey Ford and Warren Spahn.

Wright’s major-league debut was spectacular. The young hurler sliced through the first 10 hitters he faced and held the powerful Twins to just four hits. Only once did he have any problems. Already up five runs in the fifth inning, he gave up a pair of doubles that accounted for half of the Twins’ hits and their only run in the game. From there on he sailed to an easy 8-1 win, his first in the major leagues. After the game his manager, Bill Rigney, gushed: “It was the best start in the majors I’ve ever seen.” Catcher Bob Rodgers chimed in: “He did it so easy, it was effortless. … He was Mr. Cool.”5 Only new teammate Rick Reichardt had any criticism. “He was great, but we’ve got to do something about the name Clyde. From now on, he’s Skeeter Wright.”6 And from then on during his major-league career he remained Skeeter Wright.7

During the next eight weeks Wright remained part of the Angels starting rotation, winning three more games, including a shutout against the Senators, while losing five. Though his earned-run average climbed to 3.52 after a home loss to Minnesota on August 10, he consistently pitched up to his manager’s expectations. After the game with the Twins, Wright left the team to serve his summer obligation in the National Guard. When he returned in early September, he was relegated to the bullpen, making only one more start in 1966. He ended his first major-league season with four wins against seven defeats and a 3.74 ERA. By most standards, while not spectacular, it had been a respectable rookie year for the young left-hander.

Wright’s National Guard obligations also affected the beginning of his 1967 season. In early October, shortly after his rookie season, he began five months of active military service. He did not return until the following March and arrived to spring training late. He was among those pitchers who were expected to vie for the place in the California rotation vacated when Dean Chance was traded to Minnesota. Instead, Wright came to camp well behind his teammates. Consequently, two weeks before the season opener, he was one of two pitchers (Fred Newman was the other) sent to the Angels’ minor-league camp so they could get more work. Team officials assured fans that Wright was expected to be back with the parent club before season began. That did not happen.8

Wright spent the first two months of the 1967 season with Triple-A Seattle in the Pacific Coast League. As he had the previous season at El Paso, he began his minor-league stint with a flourish. By June 10, when the Angels recalled him, he had become Seattle’s ace with an 8-4 record. Once back on the parent club, he immediately staked a claim to a spot in the starting rotation. Teaming up with reliever Minnie Rojas, Wright breezed through his first three starts, winning two while Rojas won the other. In each he pitched the first seven innings and then watched while Rojas finished the games off. By the end of June he had established himself as the Angels’ fifth starter. Unfortunately for Wright, manager Bill Rigney employed a four-man rotation, which meant that Wright was used primarily as a spot starter.

In August, with the Angels in a five-team pennant race, Wright’s season was again interrupted by his National Guard obligation. When he returned a month later, the Angels had fallen six games off the pace and out of the race. Resuming his spot-starter role, he finished the season with solid starts against the Orioles and the Yankees and a couple of good relief appearances. The team, however, finished fifth in the American League. Wright ended his second major-league season with a 5-5 record and a 3.26 earned-run average.

Eager to improve his status in 1968, Wright joined fellow Angels hurler Jack Hamilton for offseason conditioning. Having completed only one of his 11 starts in 1967 (Hamilton had completed none of his 20 starts), Wright’s goal was to build endurance and strength using an Exer-Genie Exerciser. The Exer-Genie is a hand-held isometric device developed by NASA to help astronauts maintain muscle while in space. In the late 1960s many professional and college athletes had begun to use it.9 For Wright, the results seemed immediate. In his first start of the season he went nine innings, beating the Senators, 6-1. Manager Rigney raved, “That contraption is an absolutely incredible thing. …Wright has never been faster than he was Wednesday.”10

The rest of the season did not go as well. Despite his apparent new endurance and strength, Wright remained a spot starter and relief pitcher throughout 1968. He started only 13 games and relieved in 28. All of his six losses and only four of his 10 wins came as a starter. Along the way he had several notable games, including a shutout over the White Sox, his only other complete game, but it was not a satisfying year for him. Meanwhile the Angels floundered near the bottom of the American League, finishing only 1½ games ahead of the cellar-dwelling Senators.

The following year Wright’s evolving role as a reliever grew. Manager Rigney made it clear even before the season started that he intended to use Wright primarily in relief. With several young arms to assess, the Angels manager limited Wright’s innings during spring training, giving the lefty little chance to compete for a starting slot.11 Once the season began, Wright was summoned sporadically, rarely going more than two innings. His starts were few and far between. The first came on May 4 and he did not start another game for two months. The low point was August 5 against the Yankees. With two on and two out in the bottom of the ninth and the Angels up 2-0, he was called in to get the last out. Instead he served up a home run. It was the sixth of his eight losses that season. Equally disheartening, he won only a single game, saved none and finished with a 4.10 earned-run average on one of the worst teams in the major leagues. After the season the Angels considered trading Wright but had no takers. It appeared that his days with the Angels might be just about over.

Three circumstances between the end of the 1969 season and the beginning of the 1970 season transformed Wright’s career. One of those circumstances was the result of playing winter ball in Puerto Rico. Teammate Jim Fregosi, who was managing the Ponce team in the Puerto Rican league, persuaded Wright to pitch for him. He also suggested that Wright work on another pitch to add to his fastball-curveball repertoire. The solution was a screwball. By the time spring training started, Wright had perfected the pitch. He could throw it at various speeds and with the same precision with which he threw his other two pitches. Wright’s screwball transformed him on the mound.

The second circumstance actually began during the previous season. On May 27, 1969, manager Bill Rigney was fired and replaced by Lefty Phillips. While Phillips continued Rigney’s method of handling the Angels pitching staff, during the following winter he made it clear that Wright would get his chance in the starting rotation. “(Wright) came off a 10-6 season in ’68 and he just never got a chance last spring. … I know that the man has a lot of talent more than just one-game talent. Look what he did in Puerto Rico for Jim Fregosi. … No, right now Wright is my man. He’ll have to show me he CAN’T do the job.”12 Clearly the attitude about Wright’s place on the team had changed.

The third, and perhaps most important, factor in Wright’s transformation was a new level of self-confidence. After the discouraging 1969 season, “I had to do something to regain my self-respect.”13 So he agreed to play in Puerto Rico. “It was a winter for mental health. Pride came back and with it confidence.”14 But it almost didn’t happen. After losing his first two starts, one by a 10-1 score, Wright was ready to leave and so discouraged that he began considering retiring from baseball altogether. “(Fregosi) told me not to get down on myself and to stay.”15 From that point on, Wright’s winter and career turned around. He perfected his screwball, and finished the winter with a stellar 11-5 record and a real opportunity to be part of the Angels’ 1970 starting rotation.

The 1970 season started inauspiciously for Wright. Though he won his first outing, it was not impressive. He went only six innings and gave up four earned runs against the Royals. The second game, a loss to the White Sox, was a bit better. Then things started to fall in place. He went nine innings in a 7-1 win against the Royals and followed with another complete-game win over the Brewers. By June he had seven wins and three weeks later had already equaled his career-high 10-win total.

The high point of the season came on July 3. Before the game that night, Wright was inducted into the NAIA Hall of Fame. The game was against the Athletics, arguably the best power-hitting team in the American League. As he warmed up, Wright told pitching coach Norm Sherry, “If I can hold ’em to two runs tonight, we can win.” Sherry responded by telling Wright that “Roger Craig (Sherry’s former teammate) used to have the philosophy that every time he went out he’d pitch a no-hitter. Then when a team got a hit he’d say that it would be a one-hitter.”16 Wright liked the thought and carried it with him to the mound. Twenty-nine batters and 98 pitches later he had accomplished something that Craig never had. He had pitched a no-hitter, the second in Angels history and the first in Anaheim Stadium. For his work that night he became part of a second hall of fame.

The success continued for Wright. Eleven days after his no-hitter, with a 12-6 record, he took the mound in the All-Star Game. Entering the game in the 11th inning, he had the dubious distinction, an inning later, of being the losing pitcher on a play that lives on in All-Star Game history. With two out and Pete Rose on second, Wright gave up a single to Jim Hickman. Trying to score from second, Rose ferociously slammed into catcher Ray Fosse. The collision, which Wright watched from just a few feet away, effectively ended Fosse’s budding career.

Through August Wright kept racking up wins while maintaining an earned-run average below 3.00. Not even his two-week National Guard service slowed him down. Instead, he was flown in to pitch the two games he otherwise would have missed. He lost the first and won the second. By the end of August he had 18 wins. On September 16 he beat Minnesota for his 20th win and finished the season 22-12. His 2.83 ERA was the third best in the American League. He was chosen as The Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year.

During the following two seasons Wright further established himself as one of the better pitchers in the American League. Though he lost one game more than he won (16-17) in 1971, in several ways his season was comparable to his 22-win season. Most notably, he kept his earned-run average beneath 3.00. It was a season that began with great expectations for the team but quickly fell apart. On the mound the staff, led by Wright and a young flamethrower, Nolan Ryan, looked solid. Combined with an offense that included the 1971 batting champion, Alex Johnson, the Angels were expected to compete with Oakland for the American League West championship. However, a string of injuries and a season-long battle between Johnson and manager Phillips destined California to a losing season, 25½ games back of the Athletics. Before the next season began, both Johnson and Phillips were gone. Shoulder problems and a sore ankle slowed Wright early in 1972 but he finished the season with a respectable 18-11 record and a 2.98 earned-run average on one of the worst teams in the American League.

Success on the baseball diamond brought Wright a degree of local notoriety. Some suspected that Wright, an attractive bachelor making a “handsome salary” in a city of movie stars, might become the next in a line of conspicuous Angels playboys that had started with pitchers Bo Belinsky and Dean Chance.17 Wright in most ways, despite his gregarious nature, remained the same easygoing country boy he had been when he left Jefferson City. Aside from his characteristic “Tennessee twang,” he typically maintained a low profile, preferring to blend in rather than stand out. Of course, he did savor some of the benefits of his success. He bought a comfortable home near the ballpark; relished the city’s nightlife, and was often seen escorting a stunning blonde model, Vicki Holloway (they later married and had five children).18 An avid golfer, he also became a frequent participant in celebrity golf tournaments.

Wright came into the 1973 season as the fourth-winningest southpaw in the American League over the previous three seasons. His place in the starting rotation was secure, but his future with the Angels was not. During the winter Bobby Winkles had replaced Del Rice as the team’s manager and immediately began rebuilding the team. By the time of the season’s first pitch, Winkles had traded or released almost half of the 1972 roster. Wright’s work during the coming season would determine whether or not he would be part of the team’s long-term plans. It didn’t take long before doubts about Wright’s place with the Angels became a reality. Hampered by a back problem, he didn’t get his first win until mid-May, then struggled through the rest of the season, finishing with a dismal 11-19 record. Additionally, a prickly relationship with manager Winkles further soured Wright’s chances of returning with the Angels. Two weeks after the season ended he was traded to Milwaukee in a 10-player exchange.

As bad as the 1973 season had been for Wright, 1974 was worse. His new manager, Del Crandall, initially listed him as the third man in the team’s rotation. Healthy again and buoyed by a good spring training, Wright got off to a fast start, winning his first three outings and going nine innings in two of them. Then his season fell apart. He lost five of his next six starts, failing to get past the fourth inning in half of them. The worst, however, was yet to come. In mid-July Wright began a personal seven-game losing streak during which he gave up 6.17 earned runs per game. In the final two games of his streak he lasted a total of only three innings and was battered for 10 runs. The losing streak ended his days as a Brewers starter. In mid-August Crandall announced that through the rest of the season Wright would be used in relief exclusively.19 The Brewers manager lifted his edict only once. In late September, Wright was given a final start against Detroit. He came into the game with 19 losses and left in the sixth inning with his 20th loss and the highest earned-run average in his career, 4.46.

The start against Detroit was Wright’s last as a Brewer. On December 5, 1974, he was traded to Texas for pitcher Pete Broberg. It was a trade that Wright welcomed. In addition to his substandard performance on the mound, his relationship with Crandall had deteriorated steadily as the season wore on. “We just didn’t see eye to eye.” He complained that “Crandall went around asking guys if they liked me. … He asked them, ‘How come you play bad behind Clyde? Don’t you like him?’” Wright claimed that the only reason he was given his last start was because “Crandall thought I had a chance to lose my 20th game.” Crandall countered: “(Wright) is trying to put the monkey on somebody else’s back. He’s trying to disguise his own failings with a smokescreen rather than accept that he had a bad year.”20

Texas offered Wright yet another fresh start. Manager Billy Martin hoped that the acquisition would plug a left-handed hole in the starting rotation. Minimally, Wright would fortify the relief staff. Martin imagined the possibility of another 20-win season for his new southpaw.21 Wright shared Martin’s enthusiasm. With the addition of a knuckleball, he was ready for another comeback, proposing, “[S]ome people win it (Comeback Player of the Year Award) and say they never have to win it again. I’ll take it every other year if that’s the way it has to be.”22

Unfortunately for Wright, the comeback didn’t happen. He was used primarily as a starter through the first two months of the season, then he worked out of the bullpen and as a spot starter. He ended the season with a 4-6 record and a 4.44 earned-run average. The following spring he returned to the Rangers with hopes of redemption; but on April 2, he was released, thus ending his major-league career with 100 wins, 111 losses, and a 3.50 earned-run average.

While major-league teams were done with Wright, he wasn’t done with professional baseball. Within two months of his release he was pitching for the Yomiuri Giants in Japan’s Central League alongside the great Japanese slugger Sadaharu Oh. He spent the next three baseball seasons with the Giants, winning 22 games and losing 18. As with other Americans playing in Japan, Wright was paid well and felt appreciated by fans and teammates, but had problems adjusting to the daily training regime and the team’s management. Comparing his new team with his major-league teams he lamented: “Conditioning – that’s all they think about. … Spring training is four times as tough as in the States. … They go to the park at 10 and finish at 4:30 and then run 3½ miles back to the hotel.”23 While conditioning was grueling, management was a constant irritation. From his first day on a Japanese mound through his last appearance, Wright regularly collided with team executives over everything from playing time to living conditions. For his antics he was immediately dubbed “Crazy Righto” by his handlers, and “Crazy Righto” he remained for three years.

Away from the ballpark, language and cultural issues effectively isolated many of the American players. Frequently Wright filled those empty hours at bars with fellow Americans. Two of his favorite drinking companions were Charlie Manuel and former Angels teammate Roger Repoz. The threesome’s escapades added another dimension to Wright’s “Crazy” nickname but also led him to alcoholism. In 1978, upon returning from his final season in Japan, he said, “My wife (Vicki) said either I stop drinking or she was leaving me.”24 He sobered up.

After ending his career as an active player, Wright remained in the baseball world through his relationship with the Angels, whom he considered “my second family.”25 He maintained close friendships with numerous former teammates. In 2013 he was selected as 55th on the top 100 all-time Angels players list. Game days typically found him operating Clyde Wright’s Tennessee BBQ and entertaining fans with colorful baseball stories. When not at the stadium he worked to promote the Angels in other ways ranging from charity golf tournaments to drug and alcohol awareness lectures. In 1980 he founded the Clyde Wright Pitching School. Among his notable trainees were two future major leaguers, his son Jaret Wright and Kyle Hendricks. Slowed briefly by a heart bypass in 2013, Wright later returned to the golf links, gardening at the home he bought shortly after coming to Anaheim, and enjoying time with his grandchildren. He remained a popular figure with Angels fans.

Last revised: July 1, 2017

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Notes

1 William Endicott, “A Big League Pitcher Comes Home Humbly,” Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1970: 1.

2 Special Report, “Wright Called Up by Angels,” El Paso Herald-Post, June 11, 1966: 6.

3 John Wiebusch, “Winter Restores Wright’s Pride,” Los Angeles Times, March 19, 1970: 69.

4 Staff, “Wright Still Seeks Public Appreciation,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1973: 182.

5 John Hall, “Youngster Wins Debut 8-1: Angels Take a Pair,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1966: 46.

6 “Youngster Wins”: 49.

7 John Hall, “What Is a Clyde?” Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1970: 65. Four years later Hall restated his claim about Reichardt’s role in dubbing Wright “Skeeter.” Instead he attributed the sobriquet to team trainer Freddie Frederico.

8 “Angels Send Fred Newman to Holtville,” Los Angeles Times, March 28, 1967: 33.

9 Exer-Genie/history.com.

10 John Wiebusch, “Exer-Genie Works,” Los Angeles Times, April 26, 1968: 116.

11 John Wiebusch, “Winter Wins Restore Wright’s Pride,” Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1970: 69.

12 John Wiebusch, “Phillips Admits Angels Have Some Problems,” Los Angeles Times, February 25, 1970: 100.

13 “Winter Wins”: 100.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 John Wiebusch, “No-000-000-000-Hitter,” Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1970: 34.

17 Dave Distel, “Angels’ Wright Takes Tobacco Road to Success,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1973: 182.

18 Ross Newhan, “Wright Hopes for Another Comeback Award in Texas,” Los Angeles Times, December 25, 1974: 74.

19 Associated Press, “Brewers have won 5 of last 6 games,” Fond Du Lac (Wisconsin) Commonwealth Reporter, August 19, 1974: 22.

20 Associated Press, “Disagreements Caused Trade, Says Wright,” Tennessean Nashville), December 7, 1974: 19.

21 Associated Press, “Martin Says Club Rates as Favorite,” San Antonio Express, April 1, 1975: 36.

22 Ross Newhan, “Wright Hopes for Another Comeback Award in Texas,” Los Angeles Times, December 25, 1974: 79.

23 William Chapman, “Players Work Up a Sweat in the Land of the Rising Sun,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, July 15, 1978: 47.

24 Marcia C. Smith, “Wright Loves to Tell an Old Angel’s Story,” Orange County Register” October 24, 2011.

25 Ibid.

Full Name

Clyde Wright

Born

February 20, 1941 at Jefferson City, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.