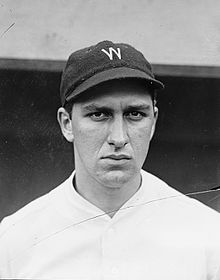

Curly Ogden

Warren Harvey “Curly” Ogden became part of World Series lore in 1924 when Washington manager Bucky Harris started him in Game Seven as a ploy to fool Giants manager John McGraw. The idea was to get McGraw to play rookie first baseman Bill Terry and other left-hand batters against the right-handed Ogden, so that Harris then could bring in lefty George Mogridge.

Warren Harvey “Curly” Ogden became part of World Series lore in 1924 when Washington manager Bucky Harris started him in Game Seven as a ploy to fool Giants manager John McGraw. The idea was to get McGraw to play rookie first baseman Bill Terry and other left-hand batters against the right-handed Ogden, so that Harris then could bring in lefty George Mogridge.

Terry, 6-for-12 at that point in the series, had not been playing against left-handers. The ruse worked. McGraw put Terry in the lineup, and Harris watched Ogden strike out Freddie Lindstrom and walk Frankie Frisch before bringing in his left-hander, who had warmed up secretly below the grandstands. The Nationals, behind the relief pitching of Walter Johnson, won in 12 innings to capture the team’s lone world championship.

In fact, Ogden played a significant role in getting the Senators, as the team was commonly if unofficially known, to the World Series. Picked up on waivers from the Athletics in May, the often sore-armed right hander went 9-5 for Washington as a spot starter. His contribution was crucial to Washington’s finishing two games ahead of the Yankees. The 1924 season was the highlight of Ogden’s five-year major-league career.

Curly Ogden was the younger brother of Jack Ogden, who also pitched in the majors and was a longtime executive and scout. Curly — he picked up the nickname as a child because of his hair — was born in Ogden, Pennsylvania, on January 24, 1901. The town was named after Ogden’s family, which had lived on land in what is now Upper Chichester Township, southwest of Philadelphia, for generations. An ancestor had come to America from England on the same ship as William Penn, and like Penn, the Ogdens were Quakers.

“There was a calf on the farm called ‘Curly,’” a local columnist wrote in 1950 about Ogden’s nickname. “There has been much discussion about who was “Curly” first: the calf or the boy.”1

Ogden’s parents were Harvey T. and Violet W. Ogden. His father owned and operated a dairy farm and also served as the township’s road supervisor for many years. His mother was a schoolteacher whose obituary in 1961 noted that she had voted in every election from the adoption of women’s suffrage through the 1960 presidential election.2 His father, two brothers, and sister-in-law all were active in local politics.

In addition to Jack (more often known as John, except during his playing days), his parents had three other sons. The youngest, Edward, born in 1903, died at age 4.3 Carroll, who went by “Tim,” was born in 1899, two years after John.

The three brothers worked on the dairy farm through their school years. All were three-sport stars at Chester High School. In the 1970s, John Ogden recalled how they would have to get up early enough to milk the cows and haul the milk to the station in order to get it on the 6:30 train into Chester. The brothers would take the same train into town for school.4

After high school, Curly enrolled in nearby Swarthmore College and, like his brother John, played football, basketball, and baseball there. Despite being two years older, Tim remained on the farm to help his father, putting off earning his degree at Swarthmore until Curly graduated. Tim’s athletic career was derailed when he suffered a serious concussion as a lineman on the Swarthmore football team.5

In high school, Curly used the name “Johnson” to pitch against older players for the Upland team in a local semipro league, presumably to protect his amateur status.6 While in college, Curly played on a basketball team called the Swarthmore Travelers, organized by his brother John to play against other teams made up of current and former high-school and college athletes. There’s no record that the players were paid for these games.7

Ogden was part of the Student Army Training Corps, a program established on more than 150 college campuses, for three months in 1918.8 World War I ended before he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry.

George Earnshaw, who became a teammate of John’s with the Baltimore Orioles and was later a pitching star with the Athletics, was Curly’s roommate at Swarthmore. But it was the 6-foot-1 Ogden who was the star pitcher in college and captain of the Swarthmore baseball team as a senior.

Connie Mack, whose Athletics played nearby, signed Curly at the end of the 1922 college term and brought him straight to the majors.9 Ogden made his debut against Cleveland in Philadelphia on July 18. He didn’t yield a run, but walked three and gave up two hits in two innings. He completed four of his six starts and appeared nine times out of the bullpen. Although he walked 33 and hit five batters in 72⅓ innings, his earned-run average was a respectable 3.11. A sore arm plagued him much of the time, however, and persisted into 1923 and ’24.

In the fall of 1922, Curly returned to Swarthmore with his brother John to help coach the college’s football team, according to a brief in The Sporting News.10

Arm trouble limited Curly to 46⅓ innings in 1923. The next season started much the same. He was 0-3 with a 4.85 ERA when Mack tried to slip him through waivers and send him to the minors. Bucky Harris sent scout Joe Engel to take a look at Ogden, and, based on a positive report, Washington picked up the pitcher for the $7,500 waiver price on May 24.

Beginning on May 26, Ogden in seven starts went 6-0 with three shutouts and a 1.58 ERA. After a loss, he won two more. Four of Ogden’s 16 starts were in the second games of doubleheaders, when pitching staffs tend to be stretched thin. Ogden won all four, pitching complete games in three and eight innings in the other. In three of those twin bills, the Senators had lost the opener.

By the time Ogden won his final game, on August 26, he was 9-3 and helping himself at bat with a .302 average. He finally wore down after losing his next start, 2-1, to the Yankees in the bottom of the ninth. Had his teammates capitalized on their 11 hits and made the plays in field — one of the Yankees’ runs was unearned — Ogden’s five-hitter might have been enough.

Instead, he essentially was done for the season. Despite the excellent results, he had worked through arm pain all year. Ogden tried to start two more games, on September 7 and September 24, but didn’t retire a batter either time. “After each day’s pitching,” Shirley Povich wrote in his 1954 team history, “he would walk the floor of the hotel suite he shared with Harris and Muddy Ruel and hold his arm in pain and wonder if he could ever work again.”11 “He amazed me every time he won a game,” Harris recalled. “Only Ruel and I could appreciate what Ogden went through. He pitched his heart out.”12

Ogden’s last appearance in 1924 was as a pinch-hitter on September 30. So it’s doubtful he expected to be called upon in the World Series. Yet no contemporary accounts indicate that McGraw knew that Ogden wasn’t really capable of pitching for long.

Harris told Ogden the night before of his plan and got approval from owner Clark Griffith.13 Curly was to face just one batter, but after he struck out Lindstrom on three pitches, Harris motioned for him to stay in. When Ogden walked Frisch, Harris put his plan into effect and brought in Mogridge.14

The game turned out to be one of the most memorable in World Series history, with bad hops aiding Washington twice and the well-loved Big Train holding down the Giants in relief until his teammates pushed across a run in the 12th to win it all.

Ogden’s gutsy performance had earned him a spot on the 1925 staff. “Curly’s work with a damaged arm last season was sensational, and it was expected that he would be even better after Bonesetter Reese fixed his wing,” The Sporting News wrote in April 1925. After Ogden’s poor spring, “Manager Harris must have figured that the Sheik of Swarthmore is a slow starter and will be all right.”15

Getting “all right” never happened in 1925, however. Although he somehow managed to pitch a shutout and complete another one of the four games he started, Ogden threw just 42 innings all year in 17 games for the pennant-winning Nats. The following season wasn’t much better. He started nine of the 22 games in which he appeared and pitched 96 innings, but his ERA was again well over 4.0, and by midseason, he found himself with Birmingham in the Southern Association. He struggled the rest of 1926 and again with Buffalo in the International League in 1927.

Ogden’s arm must have improved by the spring of 1928, however. He had the best year of his career at any level, winning 21 games with a 3.09 ERA over 242 innings with Buffalo. His 1928 performance earned him an invitation to the Giants camp in the spring of 1929. Although he pitched well, it was for naught. Apparently, manager John McGraw didn’t think Ogden’s curveball was good enough.16 He was shipped back to Buffalo as the Giants headed north.17 That spring was as close as Curly got to returning to the big leagues.

Ogden kept at it with Toledo in the American Association and Toronto, Jersey City, and Montreal in the IL into the 1934 season before calling it a career. He returned home and became the athletic director of the Chester Boys Club and was to manage the baseball team in the Chester Twilight League when he received an offer to become a coach with Montreal.18 He left for Canada, but the offer fell through. In May, the Sporting News reported that he had become the batting-practice pitcher for the Orioles during his brother John’s tenure as Baltimore’s general manager.19 Later in 1935, Curly was hired as the coach and athletic director for the new Penns Grove High School in Southern New Jersey. The school was built as a project of the Depression-era Public Works Administration. Ogden became a teacher at Penns Grove, in addition to his coaching.

As his career neared its end, Ogden married Alice Marker, of Chester, in November 1932. The couple had their only child, a daughter, Helen, in 1934. In 1940, parents and daughter were living with Alice’s father, Burton Marker, in Chester.20

Ogden’s decision to continue living in Chester and to commute to Penns Grove made for a long day in the 1930s and ’40s with daily ferry rides back and forth across the Delaware River. The bridge between Chester and Southern New Jersey, which replaced the ferries, didn’t open until 1974. As a coach, he would have returned from practice in the dark for most of the year. A commute by car would have meant driving north to Philadelphia, crossing the Ben Franklin Bridge and driving a considerable distance south to Penns Grove. Certainly, during World War II gas rationing, that would not have been an option.

Any hope Ogden might have had of getting back on the mound suffered a setback on February 20, 1935, when his right hand was injured as he exited a bus near his Pennsylvania home. The bus lurched forward and an open window fell on his hand. In court in April 1937, he was awarded $718 from the bus company for his injury.21

Ogden continued teaching and coaching at Penns Grove through the war, with many of his student-athletes drafted as soon as they graduated. In 1948, he was hired as a part-time scout by the St. Louis Browns.22 A few years later, he began scouting in the same capacity for the Phillies.23

In May 1950, Ogden suffered a heart attack and remained hospitalized for more than a month. During a long convalescence, he completed work on a master’s degree in history at the University of Delaware before returning to his duties at Penns Grove.

It wasn’t long before Ogden ran afoul of a principal with whom he did not see eye to eye. The school board accused him of “insubordination, incapacity and conduct unbecoming of a teacher,” but Ogden blamed the dispute on “dictatorial tactics by the principal.” When it became known that the school board might fire Ogden, 150 students walked out of class. Fifty of them were suspended.24

Before his heart attack, Ogden had been carrying a full teaching load and coaching three sports. “He was idolized by hundreds of students,” the Chester newspaper reported. There were more walkouts as Ogden’s case was being weighed by the school board. When the board finally fired him, Ogden soon was hired as an assistant director of admissions at Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland.25

By the mid-1950s, Ogden was back to teaching, this time closer to home at Chichester High School in Delaware County. He and Alice moved into a converted carriage house on what remained of the Ogden farm, while Tim lived in the main house. Their mother had sold off parcels of the land after their father died in the 1930s. The houses and the rest of the property were sold by Curly’s daughter after Tim, who never married, died in 1974.26

Ogden continued to teach at Chichester until his health deteriorated in 1962. He died on August 6, 1964, at Crozer-Chester Medical Center after being hospitalized for several weeks with a worsening heart condition.27

Alice Ogden had died in July 1962. Both are buried along with Curly’s parents and his brother Tim in Delaware County’s Lawn Croft Cemetery.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Bob Finucane, “Along the Streets of Chester” column, Chester Times, April 5, 1950: 11.

2 “Mrs. Ogden Is Dead at 81,” Chester Times, Nov. 13, 1961: 4.

3 http://familysearch.org/tree/person/LTC7-23Q/details.

4 Eileen Shomo, “Ogden Era Ends in Upper Chi,” Delaware County Daily Times (Upper Darby Township, Pennsylvania), December 29, 1972: 13.

5 Frank Johnson, “Sports Shorts,” Chester Times, August 27, 1949: 10.

6 Ibid.

7 “Liberty Basketball Quintet Loses First Game of Season,” Chester Times, January 3, 1919: 10.

8 Questionnaires signed by Ogden and included in his clip file at the Hall of Fame’s research center.

9 “Connie Gets Him,” Boston Post, April 18, 1922: 8.

10 “Caught on the Fly” column, The Sporting News, October 26, 1922: 7.

11 Shirley Povich, The Washington Senators (New York: G.P. Putnam & Sons, 1954), 115-116.

12 “Curly Ogden Dead at 63 — Helped Nats Cop ’24 Flag,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1964: 38.

13 Povich, 129-130.

14 Stew Thornley, “October 10, 1924: Big Train Finally Wins the Biggest One of All,” SABR Games Project.

15 Paul W. Eaton, “Washington Champions Retain All of the Old Fighting Qualities,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1925: 1.

16 Thomas W. Meany, “McGraw Watching Ogden,” New York Telegram, April 2, 1929, page unknown (accessed from Ogden’s clip file in the Hall of Fame’s research center).

17 “Ogden Shows Promise,” San Antonio Light, March 16, 1929: 4.

18 “Health Board Meets at Upland,” Chester Times, May 14, 1935: 10.

19 News brief, The Sporting News, May 23, 1935: 12.

20 1940 US Census, accessed through familysearch.org.

21 “Ball Player Gets Damages,” Chester Times, April 9, 1937: 4.

22 “Curly Ogden Gets Scouting Position,” Chester Times, November 17, 1948: 18.

23 “Phillies to Win N.L. Pennant, Predicts Scout at Glenolden Fete,” Chester Times, December 29, 1952: 4.

24 “Curly Ogden Plans to Appeal,” Chester Times, July 3, 1952: 7.

25 “Ogden Gets College Post,” Chester Times, September 29, 1952: 4.

26 “Ogden Era Ends.”

27 “Ex-Pitcher in Majors W.H. Ogden, Dies, 63,” Delaware County Daily Times, August 7, 1964: 4.

Full Name

Warren Harvey Ogden

Born

January 24, 1901 at Ogden, PA (USA)

Died

August 6, 1964 at Upland, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.