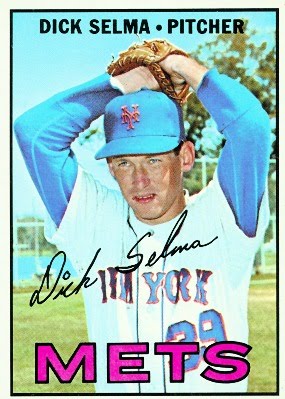

Dick Selma

His potential was glimpsed when future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan, months removed from his Rookie League debut in 1965, was said to have the ability to “throw as hard as Dick Selma.”1 That fall, Eddie Stanky, who managed Selma in the Florida Instructional League, claimed the right-handed hurler could become “the best relief pitcher in baseball”2 – a claim Selma proved correct five years later. Labeled a “flake” for the curious, often incautious wisecracks emanating from this beloved man-child, throughout his career he found himself on the receiving end of two fines, one suspension (narrowly avoiding a second), and a decking from the Philadelphia Phillies travel secretary.

His potential was glimpsed when future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan, months removed from his Rookie League debut in 1965, was said to have the ability to “throw as hard as Dick Selma.”1 That fall, Eddie Stanky, who managed Selma in the Florida Instructional League, claimed the right-handed hurler could become “the best relief pitcher in baseball”2 – a claim Selma proved correct five years later. Labeled a “flake” for the curious, often incautious wisecracks emanating from this beloved man-child, throughout his career he found himself on the receiving end of two fines, one suspension (narrowly avoiding a second), and a decking from the Philadelphia Phillies travel secretary.

Richard Jay “Dick” Selma was born on November 4, 1943, in Santa Ana, California, but earned his baseball pedigree 250 miles north, in Fresno, where he grew up alongside childhood friend and Little League rival Tom Seaver. The pair dreamed of following in the major-league footsteps of recent Fresno High Warrior graduates Jim Maloney and Dick Ellsworth. A growth spurt before his 16th birthday produced a strapping, muscular build to accompany Selma’s baseball prowess and ensured his inclusion on the Fresno High varsity baseball team during his sophomore year. Under the tutelage of coach Fred Bartels, a former Warriors athlete and minor-leaguer, Selma attracted attention from at least 15 major-league teams throughout his prep years. Unfortunately, the growth spurt that facilitated early varsity play leveled off to an average adult height of 5-feet-11 that caused scouts to question whether Selma possessed the stamina for the majors. When anticipated offers were not forthcoming, he proceeded to Fresno City College until the New York Mets inked him on May 28, 1963. “At the time I signed [a $20,000 bonus] with the Mets, the other scouts didn’t think I was strong enough to last,” Selma later said.3

Selma’s first team was the Salinas Mets, whose 1963 debut in the California League (Class A) mirrored the ineptitude of its parent. For a team that won only 49 games and lost 91, Selma became the circuit standout, accruing the most complete games, the ERA and strikeout crowns, and Rookie of the Year honors. His team-leading 12 victories (nearly a quarter of Salinas’s 49 wins) included an impressive August 31 outing against the Fresno Giants in which his 18 strikeouts – four shy of the league record – contributed to a 10-1 thumping of his hometown squad. Wid Matthews, a former major leaguer serving as chief overseer of the Mets minor-league operations, offered the following assessment of right-hander: “Best of all, he has no fear. He has a world of confidence. You never saw a fellow more determined.”4

This extraordinary launch earned Selma an invitation to “Stengel Tech,” a pre-spring player-prep in St. Petersburg, Florida. Arriving on February 7, 1964, with his wife of six days in tow (this marriage to Carolyn Kossman ended in divorce in 1975), Dick drew lavish praise from manager Casey Stengel and Hall of Famer Bill Dickey, a part-time Mets instructor, during both the two-week session and again in the formal spring-training camp. At first tempted to jump Selma from Class A to the majors, the Mets decided that he would instead profit from another year in the minors.

Assigned to the Buffalo Bisons in the Triple-A International League, the 20-year-old remained on an upward spiral – 6-4, 3.53 ERA (league average 3.56) – until just shy of the season’s midpoint. Encountering his first extended slump, Selma went winless for 31 days while his ERA mushroomed. The team moved him to the bullpen, fearing he had begun to display the previously expressed concerns regarding stamina. He finished the campaign with a 6.16 ERA over his final 22 appearances (57 innings). Despite these setbacks, a poll of the league’s managers credited Selma with possessing the circuit’s best fastball.

Selma was sent to the Florida Instructional League, but was shut down and underwent surgery in January 1965 to remove calcium deposits below his shoulder. He couldn’t throw until April, and missed spring training. To bring him along slowly, the Mets assigned Selma to Greenville in the Western Carolina League (Class A), where he rebounded brilliantly – 5-1, 2.21 ERA in his first six appearances. Selected to the All Star squad, Selma was promoted to Buffalo and was showcased in a July 22 exhibition against the parent club, striking out four in two innings.

Tapped to join the Mets when rosters expanded in September, Selma made his major-league debut on September 3 in a starting role, beating the St. Louis Cardinals 6-3 in Busch Stadium. A more impressive outing followed nine days later against Milwaukee in New York’s Shea Stadium. Selma held the hard-hitting Braves to just four hits while twirling a ten-inning shutout and establishing a team-record 13 strikeouts. His scoreless string extended another 4? innings before the Chicago Cubs reached him on September 19, and he absorbed his first loss on the 29th losing to Pittsburgh, 4-2. He finished his month-long inauguration with a record of 2-1, 3.71. The promise exhibited by Selma and another promising hurler, lefty Tug McGraw, made left-hander Al Jackson expendable, and Jackson was traded to the Cardinals for third baseman Ken Boyer in hopes of improving the Mets league-worst offense.

Selma’s promise quickly dissolved into a difficult 1966 Grapefruit League campaign followed by an equally challenging start to the season. After losing two starts he was shuttled to the bullpen while the team looked at film from the year before to determine a fix. “After that, the problem was simple,” said pitching coach Harvey Haddix. “He was throwing very deliberately then – taking his time between pitches. But this spring he was rushing things.”5 And Selma, convinced that opposing batters were detecting his pitches, began experimenting with a no-windup delivery. The results were immediate. In eight relief appearances he was credited with three wins and a save while posting a 1.88 ERA in 14-plus innings – a profitable run that earned him a return to the starting rotation. The start resulted in season-long consequences for the youngster.

On May 30 Selma took the mound in Shea Stadium against the Philadelphia Phillies. The match quickly devolved into a beanball contest, and Selma was removed in the third inning after being struck on the elbow. Rested for seven days, he returned too quickly and was set upon by the Atlanta Braves for five runs in less than two innings. Excluding a superb five-inning relief appearance in September that earned him his fourth – and last – victory of the season, Selma’s 18 appearances after the elbow injury produced a 0-5, 5.26 record that included a seven-week minor-league demotion. “He has a strong arm, but must learn another pitch,” said manager Wes Westrum. “Right now, only his fastball is effective and that’s not enough in the big leagues.”6

That other pitch became an effective curve, vastly improved upon after Selma worked with Jacksonville (Florida) Suns manager Bill Virdon through the early part of 1967. The Mets were committed to converting Selma exclusively into a reliever. Beginning with a stint at Jacksonville, Selma did well enough to get called up on June 3, and although he was pressed into four starting assignments through the season, he achieved his success in relief: 2-3, 1.96 ERA vs. 0-1, 5.82 as a starter. After a terrible training camp the following spring (0-5) that, had he not been out of options would likely have resulted in another return to the minors, Selma began the 1968 season in the bullpen until injury forced new manager Gil Hodges’ hand.

Les Rohr, a highly touted lefty, was injured and lost for the season on April 21. (The injury essentially terminated his major-league career.) Seeking someone to take the mound against Cubs on May 4, Hodges turned to Selma. The resulting 7-3 defeat of the Cubs initiated a team (and expansion club) record six straight victories (the team record standing for 18 years). On the 12th at Chicago Selma shut out the Cubs –his first complete game in three years – and until a September 10 loss possessed a particular mastery over the Cubs, with four straight wins. Dubbed one of the team’s “Young Lions”7 (a pitching staff that also included Jerry Koosman, Nolan Ryan, and Selma’s high-school teammate Tom Seaver), Selma through more than 70 percent of the “Year of the Pitcher” placed among the National League leaders in ERA. He finished the campaign with a 9-10, 2.75 record that could easily have benefited from better offensive support: He twirled a 1.72 ERA in seven starts that resulted in five losses and two no-decisions. Selma’s 1968 success, combined with assurances from Hodges that he would be protected in the pending expansion draft, made what happened next all the more surprising.

Hodges suffered a heart attack in September. During his recuperation, general manager Johnny Murphy sought unsuccessfully to send Selma to Cincinnati in a multiplayer deal involving Vada Pinson and Hal McRae, then left Selma unprotected in the expansion draft in an effort to retain promising youngsters Gary Gentry and Steve Renko. Murphy was not nearly as enamored as Hodges with Selma, viewing him (as did others) as a “hard-throwing, light-thinking right-hander”8 – a harsh assessment echoed in a 1968 comment by catcher Jerry Grote implying that Selma often lacked focus.9 San Diego, one of the expansion teams, grabbed Selma, and general manager Buzzy Bavasi quickly telegraphed that the Padres, in an effort to secure even younger prospects, were open to trades. By May 22, 1969, he had dealt five of his expansion draftees in exchange for 12 players. One trade involved Selma, but not before the righty made his mark with the National League’s new entry.

Despite a second consecutive spring training with miserable results (0-3, 7.36 in the Cactus League), Selma delivered the first pitch in the Padres’ major-league history. Surrendering a run and two hits in the first inning, he was stingy thereafter, striking out 12 and allowing only three additional hits in a complete-game 2-1 victory over the Houston Astros. He collected the franchise’s fifth win on April 22 before Bavasi sent him to the Cubs three days later. “It was a good deal for both clubs,” said Padres manager Preston Gomez. “It gives us two young pitchers [Joe Niekro and Gary Ross] we can use right away and who figure in our long-range plans. Cubs manager Leo Durocher thinks he can win a pennant with the addition of Selma.”10 Reportedly interested in securing Selma for some time, Durocher pressed him into service behind the starting trio of Ferguson Jenkins, Bill Hands, and Ken Holtzman. Excited to be pitching for a pennant contender for the first – and as it turned out the only – time, Selma chirped that he could “smell the pennant.”11

Selma’s third start as a Cub was one for the record books. A 19-0 drubbing of his recent Padres teammates tied a league record for the most lopsided shutout and, coming on the heels of consecutive whitewashes by Holtzman and Jenkins, marked the first time in 50 years that the Cubs had managed three straight shutouts. Selma rattled off six straight wins thereafter (and nine of ten), before the Cubs’ September collapse allowed the Mets to win the pennant. Selma mirrored the team’s late-season downfall; he went winless (0-6) in his last 11 appearances, but not before his efforts contributed in yet another unique and memorable manner.

For the first time in more than 20 years pennant fever ran high in North Side Chicago, with ripples emanating from Addison Street to the Cub faithful nationwide. Selma tapped into this excitement. In an age when the scoreboard-induced cheers common to a later period were barely emerging, the Cubs’ diehard Bleacher Bums fans required little inspiration for raucous cheering. But when Selma emerged from his bullpen seat to lead the crowd – an event that appears to have been initiated during the May 30-June 9 homestand – a love affair was born. “Other teams think it’s bush and maybe it is to a certain extent,” Selma told the Associated Press. “But I do it for a purpose. I’m sitting here in the bullpen one day and I think we’ve got 15,000 and 20,000 fans out here just itching to let loose for the Cubs.”12 Though Selma’s time with the Cubs was short, the memories of his cheerleading efforts may last forever.

Among the many reasons why the Cubs fell short in 1969 was the virtual turnstile that existed in right field and center field; 11 players were jockeyed between the two positions. The team saw an opportunity to improve with the acquisition of the Phillies’ veteran right fielder Johnny Callison. With a number of young pitchers developing swimmingly in the Arizona Instructional League that winter, the Cubs were confident of being able to replace any pitching lost in a trade. The cost of Callison was, in part, Dick Selma. Phillies rookie manager Frank Lucchesi told Selma he would be moved to the bullpen full-time. The move resulted in Selma’s finest major-league season, but it came at a considerable cost.

Lucchesi took an instant liking to his fellow native Californian: “They tell me Selma’s flaky. Well, if he’s what flaky is, I’ll take 24 other flakes just like him. Anything he does is aimed at keeping guys loose and making baseball more fun. Is that a crime?”13 Teamed with Joe Hoerner as the righty-lefty combination from the bullpen, Selma experienced “the time of my life”14 by matching a club-record 22 saves (fifth in the National League), more than the previous season’s entire bullpen had achieved. Throwing nothing but heat in short stints, he racked up 153 strikeouts in 134? innings and was second in the league in games pitched. After a season’s output described as “merely sensational,”15 Phillies general manager John Quinn spent much of the offseason fending off trade inquiries – including a bid from Selma’s former employer, the Mets.

The fine campaign was scarred only by Selma’s actions on September 23, 1970, when he relieved in the eighth inning against the Mets and absorbed a controversial loss that featured the ejection of three Phillies. Caught up in the turbulent postgame atmosphere, Selma questioned the integrity of the umpiring crew and suggested that the game was fixed. A subsequently contrite Selma narrowly avoided a lengthy suspension but absorbed a $500 fine.

It was the second such incident in Selma’s baseball career. In the winter of 1966, while still with the Mets, he was pitching for Caguas in the Puerto Rican League. The short season was shortened further for Selma after he responded to a booing crowd with obscene gestures. He was fined $125 and suspended by the league for a year. Selma apologized, saying, “I did not know what I was doing. It was in a moment of rage. I am very sorry.”16

The two incidents capture the essence of Dick Selma: Lacking a sense of propriety in emotionally charged moments, this big-kid-at-heart was often guilty of doing or saying something without considering the consequences. He’d earned the nickname “Moon Man” after taking the mound for the Cubs on the day of the first moon landing. A second appellation, “Mortimer Snerd,” a reference to ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s innocent, wisecracking dummy, was tacked onto Selma for his incessant talkative nature. A poorly timed quip in 1972 directed toward the Phillies travelling secretary – no shrinking violet, he was a former hockey player – resulted in a swift punch that sent Selma sprawling into the luggage carousel at the Newark Airport. But Selma’s sense of humor was evidenced that same year in an exchange with reporters who’d convinced him he’d been traded to Cleveland. Plotting retribution, Selma concocted a story about a “cosmic computer,” going so far as to develop a box containing “mysterious material” connected to straps for portable wear. His revenge was secured when one of the rookie writers wrote an article about the “computer.”

Selma never came close to repeating his 1970 campaign. Reporting to spring training the following year complaining of a tender elbow – the likely result of overuse – he managed just 11 innings before being placed on the disabled list with torn muscle tissue in his right forearm. A series of trips to Mayo Clinic, an encouraging late-season return, and a changeup developed in the winter of 1971-72 offered hope for Selma’s future. He was pressed into the starting rotation in 1972, but a 1-6, 5.27 mark resulted in a rapid return to the bullpen, where he found even less success. Released by the Phillies on May 8, 1973, Selma signed with St. Louis and was assigned to the Tulsa Oilers (to make room on the roster, the Oilers traded fellow Fresno-grown pitcher Wade Blasingame). After a dismal start in the American Association, Selma’s successful second-half campaign attracted major-league attention, and the California Angels outbid the Chicago White Sox for his services.

He earned his first American League victory in a manner befitting only Dick Selma. Renting a home near Anaheim from White Sox slugger Bill Melton, Dick entered the eighth inning of a knotted April 6 contest against Chicago and induced Melton into an inning-ending double play. The Angels scored in the following frame. In the next day’s contest, after unintentionally plunking Melton in the ninth inning, Selma quipped, “I hope Bill doesn’t jack up my rent.”17 His last win came on May 5 in relief of the pitcher who, eight years earlier, had been favorably compared to Selma: Nolan Ryan. Excluding a miserable April 28 outing in Cleveland, Selma’s record stood at 2-1, 1.17 with one save, and a team destined for last place began receiving inquiries for the righty. But Selma’s season collapsed before these talks could get under way. Sold to the Milwaukee Brewers and assigned to Triple-A Salt Lake City, he had a motorcycle accident that sidelined him. After recovering, Selma accrued two wins in six scoreless appearances (six innings) that earned an August call-up to the Brewers. He made two appearances, his last on August 9 being of the forgettable sort when he surrendered five runs in 1? innings.

A nonroster invitee for the Angels and Cubs in 1975 and 1977, respectively, Selma bounced among the Pacific Coast, Mexican, and Alaskan Baseball Leagues, and at one time tried to latch on with the Class A Fresno Giants as a player-coach. He retired after the 1978 season when major-league attention dried up completely, leaving a 42-54, 3.62 mark after 307 appearances (ten seasons). Returning to Fresno, Selma worked on the night shift for the Fleming Food Company in order to free his daylight hours playing and eventually coaching at the amateur levels. He became the assistant coach at Fresno City College, where his eldest son, Bart, served in the same capacity as of 2014.

Dick contracted liver cancer and succumbed to the disease on August 29, 2001. At his passing he was survived by his mother, Hazel; his third wife, Kathy; his children, Bart, Brett, and Beth; and four grandchildren. Bart expressed the feelings of the family, remarking “[h]e was my hero. He had a heart bigger than anyone.”18

Disguised as an adult on the major-league scene, this big-kid-at-heart left his mark, both on the baseball field and on the people he encountered throughout his 57 years. Once described as “the court jester in the Mets clubhouse,”19 this superbly talented athlete is also remembered and cherished for his zany antics. It is not hard to imagine those antics still ongoing as he leads the Cubs faithful in cheers from a much better place.

Author’s note

The author wishes to thank Len Levin for editorial and fact-checking assistance.

Sources

http://redroom.com/member/steven-robert-travers/blog/the-baseball-capitol-of-the-world-1944-64

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/7ed496e5

http://hardballtimes.com/main/article/card-corner-1973-topps-dick-selma/

http://fresnocitycollege.edu/index.aspx?page=481

http://thedeadballera.com/Obits/Obits_S/Selma.Richard.Obit.html

Notes

1 “Young Ideas by Dick Young,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1966, 14.

2 “Stanky Sizes Up Swoboda As ‘Most Untouchable’ Met,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1966, 18.

3 “Hats Off … Dick Selma,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1965, 24.

4 “Mets Grooming Fresno Flash – Twirler Selma,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1963, 16.

5 “Movies Point Out Selma’s Slab Falls to Tutor Haddix,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1966, 26.

6 “Mets Surprise Their Fans – Option Selma and Lewis,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1966, 40.

7 “Boost in Met Wins to Mean Boost in Gil’s Paycheck,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1968, 19.

8 “Mets Patting Selves On Back; Expansion Losses Very Small,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1968, 27.

9 “Jerry Sizes Up 4 Met Hill Plums,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1968, 7.

10 “Padre Weak Spot; Top of Bat Order,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1969, 22.

11 “Jimmy the Greek Cuts Odds on Cubs,” The Sporting News, May 17, 1969, 22.

12 Bruce Markusen, “Card Corner: 1973 Topps: Dick Selma,” The Hardball Times, December 13, 2013. (http://hardballtimes.com/main/article/card-corner-1973-topps-dick-selma/)

13 “Selma Saves Phils’ Bacon With Super Rescue Jobs,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1970, 8.

14 “Major Flashes: National League,” The Sporting News, September 19, 1970, 19.

15 “Relief Whiz Selma in Line for a Hefty Phil Pay Boost,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1971, 38.

16 “Criollos Release Selma After Ruckus With Fans,” The Sporting News, December 10, 1966, 43.

17 “Selma on Cloud 9 as Angel Reliever,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1974, 26.

18 “The Obit For Dick Selma,” The Deadball Era (August 30, 2001). (http://thedeadballera.com/Obits/Obits_S/Selma.Richard.Obit.html)

19 “Strutting Slugger Koosman Gets Silent Treatment,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1968, 14.

Full Name

Richard Jay Selma

Born

November 4, 1943 at Santa Ana, CA (USA)

Died

August 29, 2001 at Clovis, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.