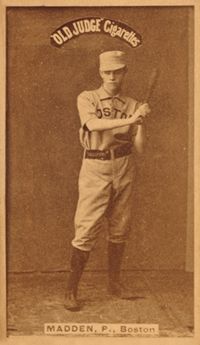

Kid Madden

Kid Madden’s career was meteoric … and tragically short. Born in Portland, Maine, on October 22, 1866, the Kid took an early liking to pitching. Though frail and almost childlike in appearance – he weighed but 124 pounds spread thinly over a 5-foot-7 frame during his peak pitching years – Madden developed an assortment of breaking pitches second to none. “He throws the most puzzling drops and curves” is how a Portland sportswriter of the time summed up the Kid’s stuff. Even years after his death, his curve, especially, was recalled with awe: “I think he could toss as wide a curve as ever was thrown,” wrote columnist Nat Colcord in a May 1909 Portland Evening Express feature story on Mainers who had played in the major leagues.

Madden hurled successfully for a number of amateur clubs in and around Portland throughout his teenage years. Given a trial by the Portland club of the New England League in 1886, he responded favorably, pitching especially well as he developed confidence – he was, after all, but 19 years old – during the course of the season. His crowning achievement came at the very end of the season: The Portlands, pennant winners in the NEL, hosted the National League Boston Red Stockings (later to become the Boston Beaneaters; then the Boston Braves; then the Milwaukee Braves; now the Atlanta Braves) in an exhibition game on October 12. Madden, on the mound for the home team, spun his breaking-ball magic and held the major-league contingent to but nine hits and four runs, going the entire route in a 7-4 Portland victory.

So impressed was Boston manager John Morrill that he signed Madden (as well as the Kid’s batterymate, Tom O’Rourke) to a Boston contract for the following year. Again, the Kid did not disappoint. As a 19-year-old rookie major leaguer in 1887, Kid Madden won 21 games while losing 14. He led the pitching staff in earned-run average: His mark of 3.79 was considerably lower than future Hall of Famer Hoss Radbourn’s 4.55; and the other two pitchers on the four-man staff, Dick Conway and Cannon Ball Bill Stemmeyer, had higher still numbers. The Kid started 37 games and, as was the custom of the day (124 pounds or not), what he started he was expected to finish. Of the 37 starts, he went the distance in all but one. There were no relief specialists in 1887.

The press of the day was high on Kid Madden. The Portland Evening Express, in its edition of May 20, reflected that “Madden is pitching intelligently,” then went on to add, “A good season’s work may be expected of him.” Later that same month, after the Kid had bested league-leading Detroit, the paper wrote, “Young Madden acted like a veteran and fooled the heavy hitters of the league completely, doing magnificent work when the bases were occupied.” A nifty seven-hit shutout of the Philadelphia Athletics on June 2 earned more Express accolades: “Madden, by his fine work in the box, strengthened the statement that he is a ‘boy wonder.’” No less an authority than the New York Times was also impressed. After the Pride of Portland threw a two-hit shutout over the New York Giants on September 8, the Times sportswriter commented: “The old saying that the New Yorks cannot bat left-handed pitching was verified here to-day, when they failed to gauge the curves of young Madden, and received a ‘whitewash’ at the hands of the Boston Club.” And a scant two days later, after the Kid had shut down the New Yorkers again, 5-2, the paper’s column headline read: “The Giants Played Good Ball But They Could Not Bat Madden’s Curves.”

Sad to say, however, the Boy Wonder was to be a one-year wonder. Whether from physical or mental exhaustion or disfavor with management, Madden pitched far less frequently in 1888 than he had in 1887. The Evening Express made note of this in its edition of August 11, 1888. “Madden sits on the bench day after day. It doesn’t seem to bother him whether he plays or not,” was the paper’s poignant reflection. The Kid, though, did start 18 games and again finished all but one of them. His last start of the season, against Pittsburgh on October 11, was far and away his best outing. He blanked the Steel City nine with but three hits. For the year his record was a disappointing 7-11. His earned-run average did drop, though, to a most respectable 2.95. (But, then again, most every other pitcher’s dropped, too. That’s because the season before – for one year only – the batters had a tremendous advantage: It took four strikes before a hitter was out. In 1888 things reverted back to the norm and pitchers could again breathe more easily.)

In 1889 Kid Madden won in double figures again. But he lost in double figures again, too. His record was an even 10-10. He started 19 games and, as one might now expect, finished all but one. A severe cold hampered much of his spring, perhaps portending the physical difficulties that were to come. Boston, now nicknamed the Beaneaters, made a run for the National League pennant that year. Led by the hitting of Big Dan Brouthers and King Kelly and the pitching of John Clarkson (who won 49 games), the Bostonians finished a scant one game behind the front-running Giants. Had the Kid been up to his 1887 form, there’s no doubt that the Beaneaters would’ve taken the flag.

Madden jumped to the newly organized Players League for the season of 1890. He didn’t jump far, however; he played for the Boston entry in the league. Nor did he have a very successful year. Although his club – fueled by Brouthers and Kelly and much of the other talent who also made the move from the Beaneaters – took the pennant by a wide margin, the Kid had a mediocre season. He started but seven games, and finished with a 4-2 record.

In 1891, with the Players League’s one-year existence now history, Kid Madden ended up in his third league in three years. He joined the American Association, again playing for the Boston team, nicknamed the Reds. It was to be his last year in the big leagues. After pitching but one game for the Reds (which he lost), Madden was rumored to be on his way to the league’s Columbus, Ohio, team. The Columbus team’s management, however, came up $200 short in its offer. Madden refused. Instead, he found himself, by early May, with Baltimore’s American Association team (known, as seemingly has been the case with just about every team that’s ever represented the city, as the Orioles). There Madden pitched well enough, winning 13 while losing 12. His batterymate for many of those games was none other than Wilbert Robinson, later to gain everlasting fame as the manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Daffiness Boys.

His major-league days behind him, Michael “Kid” Madden played for various minor-league teams – Indianapolis and back home in Portland in 1892; Portland in 1893; Haverhill in 1894 – until ill health forced him to call it a career. He died of consumption – which Webster’s defines as “a progressive wasting away of the body esp. from pulmonary tuberculosis” – on March 16, 1896, at his home at 48 Brackett Street in Portland. The Portland Daily Advertiser reported that he was “aged about 28 years.” He was 29.

Sources

This biography originally appeared in Will Anderson’s self-published 1992 book Was Baseball Really Invented in Maine? and is presented here with the author’s permission. Bill Nowlin has added new material and slightly revised the original version.

Full Name

Michael Joseph Madden

Born

October 2, 1867 at Portland, ME (USA)

Died

March 16, 1896 at Portland, ME (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.