Dan Brouthers

“Nature formed but one such batsman as [Dan] Brouthers and then destroyed the die.”1 — Boston Globe, June 3, 1889

Brouthers “is the best batter that ever faced a pitcher—bar nobody. He is the daddy of all hitters.”2 — Cincinnati Enquirer, October 15, 1893

One of the greatest hitters in baseball history, first baseman Dan Brouthers hit for power and average. Among 19th-century players, his .520 career slugging percentage is the highest and his .342 career batting average ranks third, behind Ed Delahanty (.346) and Billy Hamilton (.344). Brouthers hit .300 or better in 16 consecutive seasons, 1881-96.

One of the greatest hitters in baseball history, first baseman Dan Brouthers hit for power and average. Among 19th-century players, his .520 career slugging percentage is the highest and his .342 career batting average ranks third, behind Ed Delahanty (.346) and Billy Hamilton (.344). Brouthers hit .300 or better in 16 consecutive seasons, 1881-96.

He was born Dennis Brooder on May 8, 1858, at Sylvan Lake, New York. At the time of the 1860 US Census, he lived in nearby Beekman with his parents, Michael and Anne (née Eagen3) Brooder, older siblings Martin and Ellen, and younger brother James. The region attracted Irish immigrants to the iron industry. Michael and Anne came from the Emerald Isle, and Michael worked as an “iron furnace man.”4

The family’s surname is spelled “Bruder” in the 1870 US Census. That year they resided in Fishkill, New York. Soon after, they moved to nearby Wappingers Falls, where Michael and teenage Dennis worked in factories that produced dyed cloth.5 During his baseball career, Dennis Bruder became known as Dan Brouthers, pronounced “Brew-thers.”

As a member of the semipro Actives of Wappingers Falls, Brouthers considered giving up baseball after a tragic accident. Running the bases on July 7, 1877, he collided at home plate with catcher John Quigley. Brouthers’ knee struck Quigley’s head and fractured his skull, an injury that proved fatal.6

In 1879 Brouthers played first base for Troy, New York, in the National League. In his debut on June 23, he got one hit, a double, in five at-bats off Syracuse pitcher Harry McCormick.7 On July 19, facing Cincinnati pitcher Will White, he clouted his first major-league home run, though it should have been a double; the ball “slipped into a hole in the fence, and he made the circuit before it could be recovered.”8 The next year, he played for independent teams in Baltimore and Rochester, New York, and appeared in three games for Troy.

In 1881, after brief stints with the minor-league New Yorks (of New York City) and Brooklyn Atlantics, Brouthers returned to the National League with the Buffalo Bisons. On June 21, he hit a single, triple, and home run off Troy’s Mickey Welch.9 Brouthers helped the Bisons to a third-place finish and led the league in home runs (8), extra-base hits (35), and slugging percentage (.541).

Brouthers was a left-handed batter and right-handed thrower.10 At 6-feet-2 and 200 pounds, he was described as “massive”11 and “gigantic,”12 and was nicknamed “Jumbo” after P.T. Barnum’s famous elephant.13 But “Big Dan” was agile and as “nimble as a cat.”14

On June 21, 1882, facing Troy’s Tim Keefe, Brouthers made “a magnificent hit over the right field fence for a home run.”15 At Boston on August 18, his home run traveled far over the right-field fence and the ball was lost.16 Ordinarily, the ball was retrieved and kept in play, but this one reached “unexplored regions.”17

“Big Brouthers, of the Buffalos, is the brawniest brandisher of the bludgeon that ever belted a ball,” wrote an alliterative reporter.18 Brouthers’ “bludgeons” were long and heavy. One of his bats from the early 1880s in the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame measures 41½ inches and 38 ounces.19 (By comparison, Aaron Judge used a 35-inch, 33-ounce bat in 2022.20)

The Bisons finished in third place in 1882. Brouthers won the batting title with a .368 average and led NL first basemen with a .974 fielding percentage. He won the batting title again in 1883 with a career-high .374 mark, yet the Bisons dropped to fifth place. On July 19, 1883, he went 6-for-6 in a 25-5 thrashing of Philadelphia.21 Meanwhile, his brother James debuted for Grand Rapids, Michigan, in the Northwestern League. James played in the minors for nine seasons, 1883-91.

In 1884 Brouthers slugged a career-high 14 home runs for the third-place Bisons. His home run off George Weidman at Detroit on August 2 was a tape-measure blast; “the ball was still far in the outfield” when he crossed home plate.22 Detroit’s Frank Meinke wouldn’t let Brouthers beat him; on June 19 he intentionally walked the feared slugger four times.23

At first base, Brouthers became a master of the hidden-ball trick. On July 18, 1884, he fooled Chicago’s Michael “King” Kelly. In the seventh inning, Kelly reached first on a throwing error, “and when the little excitement subsequent to play had subsided, Kelly stepped from the bag, and Dan in a very cool way touched him out.”24

In the offseason Brouthers resided in Wappingers Falls. He married Mary Ellen Croak, a local lady of Irish descent. They had five children, four living at the time of the 1900 US Census: Anna Brouthers (born in 1886), Daniel (1888), Dennis (1890), and Margaret (1894).

Brouthers’ .359 batting average in 1885 ranked second in the National League. A seventh-place finish and financial troubles brought an end to the Bisons. The team was sold to the sixth-place Detroit Wolverines, whose primary interest was acquiring Buffalo’s four best hitters. Known as the “Big Four,” they were Brouthers, Hardy Richardson, Jack Rowe, and James “Deacon” White. Bolstered by the new men, the Wolverines vied for the 1886 pennant but fell short, 2½ games behind the first-place Chicago White Stockings.

Brouthers batted .370 that year with a career-high slugging percentage of .581. The Detroit Free Press endeavored to describe his power: He sent a “thunderbolt” from his bat or a “cannon shot,”25 and the ball sailed up and away on “an astronomical investigating tour.”26 The Boston Globe saw color: “Dan Brouthers turned the air blue with a liner to centre field.”27

At Chicago on September 10, 1886, Brouthers hit a single, double, and three home runs off Jim McCormick.28 It was one of 11 times in the 19th century that a National Leaguer hit three or more homers in one game.29

With a powerhouse lineup, the Wolverines captured the 1887 NL pennant. Brouthers led the league in runs (153) and extra-base hits (68), and his .338 batting average ranked third. In the regular season finale, he sprained an ankle while stealing second base.30 The injury kept him out of all but one game of the World Series against the St. Louis Browns, champions of the American Association. The Wolverines won the Series, 10 games to 5.

Brouthers kept on hitting the next year, and the Wolverines stood in first place on July 27, 1888. But the team went into an unfathomable tailspin, losing 16 consecutive games, and finished the season in fifth. Brouthers led the circuit with 118 runs, and his .307 batting average ranked fourth (the league average was .239). The financially strapped club was disbanded, and Brouthers was acquired by Boston. Among the elated Bostonians was sportswriter Tim Murnane, who wrote that Brouthers “can play first base to perfection” and is one of “the greatest batsmen ever known to the base ball field.”31

Ned Hanlon, who was Brouthers’ teammate on the Wolverines, said Brouthers “could hit all pitchers and his drives were longer and harder than those of any other player.”32 Murnane described Brouthers’ left-handed batting stance as “close to the plate” with “feet well apart” and noted that he seldom swung at a bad pitch. Murnane added, “Fielders never know how to play for him, as he is just as likely to hit to right as he is to left field.”33

Brouthers was as good as advertised in 1889. He lifted Boston to second place in the National League and led the majors with a .373 batting average. Incredibly, he struck out only six times in 565 plate appearances, a ratio of one strikeout per 94 plate appearances. That year, the major-league average was 8.5 strikeouts per 94 plate appearances. (The ratio in 2024 was 21 strikeouts per 94 plate appearances.)

Actively lobbying for players’ rights, Brouthers served as vice president of the Brotherhood, a players’ union organized by John Ward,34 and joined the union’s new Players League for the 1890 season. His team, the Boston Reds, won the pennant. The league folded after one season, and the next year he played for the Boston Reds of the American Association. His team again won the pennant, and his .350 batting average led the majors.

With the demise of the American Association after the 1891 season, Brouthers returned to the National League on Ward’s 1892 Brooklyn team. He won his fifth batting title, and Ward called him “the greatest hitter on earth.”35 In 1893, following a bout with influenza in the spring,36 Brouthers appeared in 77 games for Brooklyn. After the season he was traded to the Baltimore Orioles.

The 1894 Orioles, managed by Ned Hanlon, won the NL pennant with a stellar 89-39 record. The team was stacked with future Hall of Famers: Wilbert Robinson, catcher; Brouthers, first base; Hughie Jennings, shortstop; John McGraw, third base; and Willie Keeler and Joe Kelley, outfield. “I think it is the strongest club that was ever put together,” said Brouthers.37 He batted .347 and clouted the offerings of the best pitchers in baseball. He went 3-for-5 facing Amos Rusie of the New York Giants on Opening Day, April 19; 4-for-5 off Boston’s Kid Nichols on June 18; and 3-for-4 against Cy Young of the Cleveland Spiders on September 3.38 But this was Brouthers’ final full season in the majors.

After a falling out with Hanlon in the spring of 1895, Brouthers was sold to a National League doormat, the Louisville Colonels.39 He appeared in only 24 games for the Colonels before leaving to care for his sick wife.40 During his short time with the team, he provided hitting instruction to teammate Fred Clarke, an aspiring 22-year-old outfielder and future Hall of Famer. Brouthers “could murder a low curve,” remembered Clarke in a 1951 interview. With tutoring from Brouthers, Clarke learned to hit that pitch.41 And Brouthers helped another future Hall of Famer by suggesting that teammate Jimmy Collins, then a struggling outfielder, be moved to third base.42 Collins became one of the greatest third basemen of the era.

Brouthers returned to baseball in the spring of 1896 with the Philadelphia Phillies, who had purchased his contract. He hit .344 in 57 games, but at age 38 he was regarded as old and expendable, and was released on July 4.43 He finished the season with the Springfield (Massachusetts) Ponies of the Eastern League and batted .400 in 51 games.44

The next year, Mark Twain famously declared, “The report of my death was an exaggeration,”45 and Brouthers proved that he, too, was not finished. On the 1897 Ponies, he pounded Eastern League pitching and led the circuit in hits (208), doubles (44), batting average (.415), slugging percentage (.645), and total bases (323). And his fielding percentage (.983) ranked second among the league’s first basemen.46

In 1898 Brouthers batted .333 in 50 games for Springfield and Toronto, but only .235 in 45 games the following year for Springfield and Rochester. Discouraged by his decline, he announced his retirement from professional baseball on July 5, 1899.47

Back home in Wappingers Falls, Brouthers was a hotelkeeper and saloonkeeper.48 He came out of retirement in 1903 to play for neighboring Poughkeepsie in the Hudson River League. He hit .286 in 16 games that year and led the league with a .373 average in 117 games in 1904. On June 1, 1904, the 46-year-old slugger went 6-for-6 with two grand slams in Poughkeepsie’s 18-8 rout of Saugerties, New York.49 The Buffalo Courier called him “the wonder of the baseball world” and “probably the greatest batter that this country has ever produced.”50 To honor him, manager John McGraw of the New York Giants put him in the Giants lineup on October 3 and 4, 1904; these were his final major-league games.51

Brouthers played one more year for Poughkeepsie, hitting .296 in 81 games in 1905. The next year, he was playing manager and owner of the Newburgh, New York, team in the Hudson River League. However, this venture was a financial failure, and he relinquished the franchise midseason.52 Soon after, he moved his family to New York City and began a second baseball career in the employ of McGraw and the Giants.

Initially, Brouthers served as a scout for the Giants; among his finds were first baseman Fred Merkle and second baseman Larry Doyle. In later years, Brouthers worked at the Polo Grounds, the Giants’ ballpark, as a ticket taker, press-box attendant, and night watchman.53

On August 2, 1932, at his home in East Orange, New Jersey, Brouthers died of a heart attack at the age of 74. He was interred at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Wappingers Falls. In 1945 he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. And in 1971 he was memorialized by a monument and baseball field named Brouthers Field in Wappingers Falls.54

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Steve Ferenchick.

Sources

Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com, accessed in 2024.

Kerr, Roy. Big Dan Brouthers: Baseball’s First Great Slugger (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), 2013.

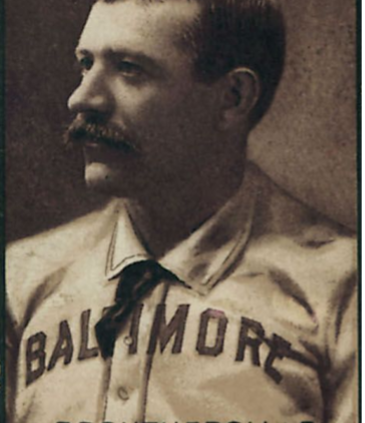

Image: 1895 Mayo’s Cut Plug baseball card of Dan Brouthers.

Notes

1 “Notes of the Diamond,” Boston Globe, June 3, 1889: 4.

2 “All Sorts from the Sporting World,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 15, 1893: 10.

3 Findagrave.com, accessed February 2024.

4 1860 US Census.

5 Roy Kerr, Big Dan Brouthers: Baseball’s First Great Slugger (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 6, 7.

6 Kerr, Big Dan Brouthers, 12, 13.

7 “Other Field Sports,” Chicago Inter Ocean, June 24, 1879: 5.

8 “Cincinnati vs. Troy,” Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1879: 6.

9 “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, June 22, 1881: 3.

10 “Buffalos for 1885,” Buffalo Times, February 23, 1885: 3.

11 “B.B. Superstition,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 30, 1882: 10.

12 “Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 18, 1882: 5.

13 “Sporting,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, April 29, 1882: 3.

14 “The Champions,” Boston Globe, October 11, 1887: 3.

15 “Astonished Themselves,” Buffalo Express, June 22, 1882: 4.

16 “Boston 9, Buffalo 8,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1882: 8.

17 “The Diamond,” Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, September 3, 1882: 5.

18 “Base Ball,” Fall River (Massachusetts) News, August 28, 1882: 3.

19 Kerr, Big Dan Brouthers, 54.

20 Bernie Woodall, “Home Run Slugger Aaron Judge Uses Bats Made on Treasure Coast,” September 26, 2022, available online at Treasure Coast Business, tcbusiness.com.

21 “Ferguson’s Fumblers,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, July 20, 1883: 3.

22 Sporting Life, August 13, 1884: 3.

23 “Almost Slaughtered,” Buffalo Times, June 20, 1884: 1.

24 “Sporting Notes,” Buffalo Times, July 19, 1884: 4.

25 “Weidman Tried to Win,” Detroit Free Press, June 17, 1886: 8; “Culture Crushed,” Detroit Free Press, July 3, 1886: 3.

26 “Eleven Straight,” Detroit Free Press, May 22, 1886: 3.

27 “Ubbo There,” Boston Globe, July 13, 1887: 3.

28 Sporting Life, September 15, 1886: 4.

29 “Three Home Runs in a Game,” Baseball-Almanac.com, accessed February 2024.

30 “No More,” Detroit Free Press, October 9, 1887: 6.

31 Tim Murnane, “Killed by Stars,” Boston Globe, November 15, 1888: 4.

32 “From 1887 to 1897,” Sporting Life, September 11, 1897: 21.

33 “Great Batters,” The State Republican (Lansing, Michigan), July 1, 1889: 2.

34 Kerr, Big Dan Brouthers, 85.

35 “Ward Captures a Prize,” New York Herald, February 17, 1892: 8.

36 “Dan Brouthers Has the Grip,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, May 3, 1893: 1.

37 “Why They Win,” Sporting Life, September 22, 1894: 6.

38 Sporting Life, April 28, 1894: 4; Tim Murnane, “They Quit Even,” Boston Globe, June 19, 1894: 5; Sporting Life, September 8, 1894: 3.

39 “Brouthers a Colonel,” Sporting Life, May 11, 1895: 2.

40 “Louisville Lines,” Sporting Life, June 29, 1895: 7.

41 Joe King, “‘The Wonder Man’ of Pittsburgh,” The Sporting News, March 14, 1951: 15, 16.

42 “Brouthers Developed Collins,” Oakland Enquirer, August 26, 1899: 12.

43 “Brouthers Released,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 5, 1896: 8.

44 Sporting Life, November 28, 1896: 6.

45 Frank Marshall White, “Mark Twain Amused,” New York Journal and Advertiser, June 2, 1897: 1.

46 Sporting Life, February 5, 1898: 10.

47 “Dan Brouthers Quits,” Meriden (Connecticut) Journal, July 6, 1899: 4.

48 1900 US Census; “Various Troubles,” Sporting Life, December 8, 1900: 1.

49 “Hudson River League,” Poughkeepsie (New York) Eagle, June 2, 1904: 2.

50 “Old Dan Brouthers, The Wonder of the Baseball World,” Buffalo Courier, June 5, 1904: 27.

51 “Giants End Local Season in Big Row with the Umpire,” New York World, October 4, 1904: 1; Sporting Life, October 15, 1904: 8.

52 “Hudson River League,” Sporting Life, July 14, 1906: 17.

53 Kerr, Big Dan Brouthers, Chapter 7.

54 “Dan Brouthers Monument,” BallparkReviews.com, accessed December 2024.

Full Name

Dennis Joseph Brouthers

Born

May 8, 1858 at Sylvan Lake, NY (USA)

Died

August 2, 1932 at East Orange, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.