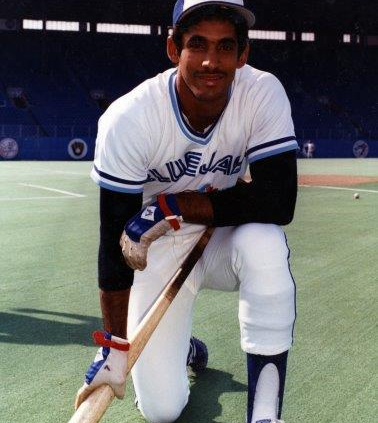

Dámaso García

Dámaso Domingo (Sanchez) García, an 11-year major leaguer (1978-1989), began his career with the New York Yankees, but the second baseman-shortstop is best known for his seven seasons with the Toronto Blue Jays. His playing days ended with brief stints in Atlanta and Montreal. His final appearance with the Expos came on September 12, 1989.

Garcia was born in Moca, Dominican Republic, on February 7, 1957, to Dámaso García Bautista, a farmer, and Juana Sanchez Nuñez, a housemaid. The elder Garcías met in college and later married in San Francisco de Macoris, Juana’s hometown.1

Dámaso had an unusual path to the major leagues. He began playing soccer at age 7, became a local star, playing as central defender, and received a scholarship to play soccer for Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra in Santiago (where he also participated in track and field, and studied mechanical engineering for two years.2) He was captain of the Dominican Republic national soccer team when New York Yankees scout Epy Guerrero signed him as an amateur free agent in March of 1975.3 He had played baseball as a boy but had been away from the game for four years after his soccer coach ordered him to not play baseball.4

Despite those four years away from the game, García found immediate success in the minors. His first assignment was to Oneonta of the Class-A New York-Penn League. He showed skill with the bat, hitting close to .300 before a late-season slump left him with a .268 batting average.5 His fielding was suspect (17 errors in 49 games) but quickly improved. He would become a solid defensive player in his major-league career with a lifetime .980 fielding average. Years later García reflected on the season spent at Oneonta as the key to his major-league career. Specifically he credited manager Mike Ferraro, saying, “I didn’t know how to catch a ball, I didn’t know how to turn a double play, I didn’t know how to hit. I had to learn everything and I was trying to learn English at the same time. Everything was work, work, work. I owe it to Mike Ferraro. He had all the patience in the world with me.”6 Ferraro recalled, “We had extra workouts every afternoon in spring training. I had to show him how to use the four corners of the bag for different situations.”7 According to Ferraro, García possessed tremendous natural talent with a powerful arm and great range at second base.8 Combining those in-born abilities with the hard work of 1975 helped him to blossom into a big-league talent.

García maintained an upward trajectory in the minors over the next three seasons. In 1976 he was moved from Low A (Oneonta) to High A (Fort Lauderdale). The following season was spent in West Haven of the Double-A Eastern League and in 1978 he manned second base for Triple-A Tacoma. A midseason injury to the Yankees’ Willie Randolph brought García his first big-league appearances the same year. 9

García’s major-league debut came on June 24, 1978, in Detroit, when he was inserted at second base in the bottom of the eighth. The next day he got his first start and went 2-for-4 against the Tigers. He grounded out his first time up, but singled in the fifth against the Tigers’ Steve Baker and again in the ninth against John Hiller. His first RBI came against the Boston Red Sox on June 27, on a sacrifice fly against Jim Wright. It was his only run batted in of the year. He batted just .195 in 18 games, but he had tasted the majors at last.

In 1979 the 6-foot-1, 165-pound right-handed batter was back at Triple-A (Columbus) except for a brief September call-up. With Randolph deeply entrenched at second, the Yankees used García in 10 games at shortstop and one at third base. It was clear that he was expendable to the team. In November 1979 he was part of a deal with the Blue Jays that sent him along with Paul Mirabella and Chris Chambliss to Toronto in exchange for Rick Cerone, Tom Underwood, and Ted Wilborn.10

With Toronto García flowered into a solid player. Even before spring training arrived the Blue Jays were confident that he would be their second baseman in 1980.11 García demonstrated that the team had good reason for trusting in his abilities. In his first full major-league season he hit .278 in 140 games with 30 doubles and 13 stolen bases. He made 16 errors at second base, but was also involved in turning 112 double plays as he began his tandem with shortstop Alfredo Griffin (a pairing that would last until Tony Fernandez took over at short in 1985). Toronto batting instructor Bobby Doerr(a fine second baseman in his own right) was impressed with García’s talent: “He’s going to be a good hitter. In the next three or four years, he’s going to hit 15 to 18 home runs. He’s got such a quick stroke.”12 (For the record, García never hit more than eight home runs in a season.) García’s rookie year performance did not go unnoticed as he finished fourth in the American League Rookie of the Year voting and placed second behind Joe Charboneau for The Sporting News AL Rookie award.13 He was also recognized by Topps, which named him as second baseman on its 1980 Rookie All-Star Team.14

García’s 1981 campaign proved less successful, primarily due to injuries. He had a team-high 48 days out of the lineup during the strike-shortened season. His ailments included flu, a sore right knee, and a broken bone in his right hand after Ed Farmer hit him with a pitch.15 His batting average dipped to .252 in just 64 games.

Undeterred by the rash of injuries in 1981 García returned in 1982 to have the finest season of his career. Manager Bobby Cox moved him to the leadoff spot in the lineup.16 He responded with a slash line of .310/.338/.399, lashing 32 doubles and ranking second in the American League with 54 stolen bases (trailing only Rickey Henderson). García established team records with his 54 SBs, 185 hits, and 89 runs scored.17 He earned a Silver Slugger Award for his efforts.18 The Sporting News named him its American League All Star at second.19

García was frustrated with the business side of the game. Before the 1982 season began, he chose to forego use of an agent and negotiated a two-year contract for $300,000 with Toronto general manager Pat Gillick. However, when he reported to spring training he refused to sign the contract, and as a result the Jays renewed his contract for one year at $90,000.20 After the season he went to arbitration, this time with agent William Goodstein representing him. García won the case and was awarded the $400,000 he asked for, but he was furious and asked to be traded after the Blue Jays argued that he was undeserving of that amount and countered with an offer of $300,000.21 Gillick had this to say about the negotiations: “We presented the facts, we did not try to knock him down. We don’t intend to trade the guy, and we are under no obligation to do so.”22

Despite Gillick’s statement denying a possible trade of García, he was the subject of regular trade rumors after the 1983 season. He was included in discussions with Seattle, Texas, the Chicago White Sox, St. Louis, and Montreal.23 In the end none of those deals materialized and García was signed by Toronto to a five-year deal before the 1984 season began.24

García’s performance remained solid before and after the negotiations and trade rumors. In 1983 he hit .307 and swiped 31 bases; he followed that with a .284 average and 46 steals in 1984. The Blue Jays were becoming contenders, and García was seen as the sparkplug for the Toronto offense. Teammate Dave Collins saw him as “our catalyst, he’s a tremendous athlete.”25

The Blue Jays finished in second place in the AL East in 1984 and improved in 1985 to win the division with a 99-62 record. In its first postseason appearance, Toronto fell in seven games to Kansas City in the 1985 American League Championship Series. García had seven hits in the series, including four doubles, and scored four runs. He was named to The Sporting News American League All-Star team.26 García was selected as a reserve for the 1984 and 1985 All-Star Games.

The 1986 season began with a disgruntled García. In spring training new Blue Jays manager Jimy Williams announced that Lloyd Moseby would move to the leadoff spot with Dámaso dropped to the ninth spot.27 This move infuriated García. Rather than thriving at the bottom of the order, he entered a prolonged slump to begin the season. After a loss in Oakland on May 14, García made perhaps the worst mistake of his career by burning his uniform. In 1987 he said, “My one regret is burning my uniform. I regret what I did and I will always regret it. I meant no harm.”28 His actions brought a rebuke in front of the entire team by manager Williams.

In August García and teammate Cliff Johnson got into two fights during batting practice before a game. García was upset that Johnson (who was on the disabled list) was allowed to take batting practice with the active roster players.29According to witnesses, García took the first swing but missed Johnson. Johnson then hit García in the side of the head and a wrestling match ensued. Teammates had to separate the two players.30 García was banished to the clubhouse, but returned later to reignite the fisticuffs. Manager Jimy Williams and other players intervened to break up the second fight.31

After his tumultuous 1986 season it was no surprise that García found himself traded to Atlanta with Luis Leal in exchange for Craig McMurtry. Former Blue Jays manager Bobby Cox had moved to Atlanta as general manager and arranged the deal. He had succeeded in motivating the moody García in Toronto and it was hoped he could do the same with the Braves.32

As it turned out, a knee injury sidelined García for the entire 1987 season. He found this situation extremely frustrating: “I’m desperate to play, I’m desperate to get well and help this club. I want to play, but going crazy won’t help.”33 He did return in 1988 but slumped badly, batting just .133 in 30 at-bats to start the season. Bobby Cox remained confident as he remembered the past streaky hitting of García. “He wouldn’t hit, and then all of sudden there would be a four-hit game, a two-hit game, another four-hit game,” Cox said. “That’s why I’m not worried about it. He always comes out of it.”34A little over a month later the still-slumping second baseman was released. Cox lamented, “We really thought Dámaso could help us. I don’t know what happened, but somewhere Dámaso lost interest in playing. We just couldn’t have that on the club.”35

After being dropped by Atlanta, García signed with the Dodgers and was assigned to Triple-A Albuquerque. He played in just three games before reinjuring his knee.36 Los Angeles quickly released him. Before the 1989 season he signed with Montreal. His performance was closer to his career norms as he appeared in 80 games and managed a .271 batting average. Late in the season the Expos, who were well out of playoff contention, benched García in order to give some younger players a look.37 García’s original club, the Yankees, gave him one last chance in 1990 but released him during spring training.38 García reconciled himself that his career was in the past. “No one has called,” he said a couple of months into the season. “But even if they did, I wouldn’t play anymore. I’ve had enough.”39

Knee injuries had hampered García’s playing career, but a much worse health problem awaited him in retirement. In 1991 he began experiencing double vision, which led to discovery by doctors of a malignant brain tumor.40 After he recovered from surgery and chemotherapy, he returned to Toronto in 1992 to toss the first pitch to former teammate Alfredo Griffin before Game One of the American League Championship Series.41 As a result of the cancer surgery and treatment, García suffers from limited speech and motor skills.42

In 1985 it was discovered that García’s 6-month-old son, Dámaso Alejandro, suffered from hemophilia. He had received top-notch care throughout his father’s playing days. García’s wife, Haydée, was astounded by the limited medical care available when they returned to the Dominican Republic after her husband’s baseball career ended.43 Dámaso and Haydée started an organization to provide workshops to Dominican families whose children have the condition. In 1998 they founded a baseball camp to raise awareness and funds for children with hemophilia.44 In the years following other players have contributed to the effort, including Tony Fernandez, Pedro Martinez, and Moises Alou.45 In 2012 Haydée was recognized with the Novo Nordisk Haemophilia Foundation Community Award.46

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Haydee Garcia, email correspondence with Bill Nowlin, July 11, 2017.

2 Ibid.

3 John Brockman, “Garcia Kicks Soccer Habit in FIL,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1975: 23.

4 Brockman.

5 Brockman.

6 Joe Gergen, “From the Heart: Minor League Mentor Mike Ferraro Gets a Message from Garcia: Thank You!” The Sporting News, October 28, 1985: 11.

7 Gergen.

8 Gergen.

9 Phil Pepe, “Yankees Purify the Air – And Billy Breathes Easier,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1978: 19.

10 Arlie Keller, “Chambliss May Be Dealt Again,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1979: 57.

11 Neil MacCarl, “Blue Jays Ponder Howell’s Role,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1980: 41.

12 Neil MacCarl, “Blue Jays Got the Message to Garcia About Hitting,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1980: 10.

13 Bob Sudyk, “Top 1980 Rookie Players: Joe Charboneau,” The Sporting News, November 22, 1980: 42.

14 “A.L. Tops in Rookies,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1980: 56.

15 Neil MacCarl, “Strike Didn’t stop Jays from Hurting,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1982: 46.

16 Neil MacCarl, “Jays’ Garcia Earns Super Rating at 2B,” The Sporting News, June 14, 1982: 27.

17 Neil MacCarl, “Jays Finish Strong, Best Record Ever,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1982: 41.

18 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “The Silver Sluggers,” The Sporting News, November 15, 1982: 50.

19 Ben Henkey, “In the A.L. Right Makes Might,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1982: 28.

20 “Jays’ Garcia Earns Super Rating at 2B.”

21 Neil MacCarl, “Garcia Is Furious Despite Salary Win,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1983: 35.

22 MacCarl, “Garcia Is Furious Despite Salary Win.”

23 Peter Gammons, “Only Stupidity Could Deprive Aparicio,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1983: 58.

24 Neil MacCarl, “Upshaw, Garcia Sign for Five Years,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1984: 36.

25 Stan Isle, “Garcia Sparks Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1984: 32.

26 “1985 TSN All-Star Squads,” The Sporting News, October 28, 1985: 18.

27 Dave Nightengale, “Repeating: Why Is It So Difficult?” The Sporting News, April 1, 1986: 9.

28 “Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1987: 31.

29 “Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1986: 21.

30 “Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1986: 21.

31 “Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1986: 21.

32 Moss Klein, “Can New Blood Rid Angels of Old Curses?” The Sporting News, February 16, 1987: 30.

33 Gerry Fraley, “Braves Wait for García,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1987: 16.

34 Gerry Fraley, “García, Braves Slump Together,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1988: 16.

35 Gerry Fraley, “García’s Disappointing Stay Ends,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1988: 19.

36 Ian MacDonald, “García Opens Comeback with Early Heroics,” The Sporting News, April 17, 1989 :22.

37 “Expos,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1989: 18.

38 “Ex-Blue Jay García Happy Down on the Farm – His Own,” Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1990.

39 “Ex-Blue Jay García Happy Down on the Farm – His Own.”

40 Paul White, “García Still Making a Difference,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, February 26, 2002: 4.

41 Tim Wendel, “García Comes Back to Throw First Pitch,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, October 20, 1992.

42 “García Still Making a Difference.”

43 Wendel.

44 Wendel.

45 Wendel.

46 “How Family History Led to Award-Winning Commitment,” nnhf.org/news_and_events/nnhf_news/dominican_republic_award.html.

Full Name

Damaso Domingo Garcia Sanchez

Born

February 7, 1957 at Moca, Espaillat (D.R.)

Died

April 15, 2020 at Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.