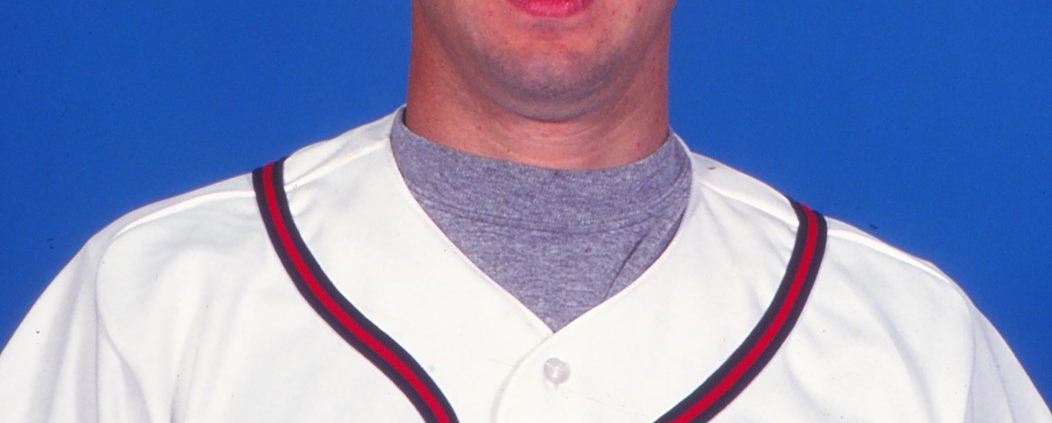

Darrell May

Even though any player who reaches the major leagues is supremely talented, perseverance is a key factor for many of them. The ability to keep trying often separates major and minor leaguers. For Darrell May, perseverance included transitions between several organizations and a stint in Japan, before finding himself as the leader of the pitching staff on a surprising team, and then narrowly avoiding the stigma of a 20-loss season.

Even though any player who reaches the major leagues is supremely talented, perseverance is a key factor for many of them. The ability to keep trying often separates major and minor leaguers. For Darrell May, perseverance included transitions between several organizations and a stint in Japan, before finding himself as the leader of the pitching staff on a surprising team, and then narrowly avoiding the stigma of a 20-loss season.

Darrell Kevin May was born on June 13, 1972, in San Bernardino, California. The son of Robert and Judy May, he joined a family that already included older brother Jeff, 10½ years Darrell’s senior. Robert May grew up in West Virginia, one of 12 children in his family. After working in the coal mines, he joined the Air Force and served as a mechanic. Out of the service, he went to work as a cable splicer for many phone companies. Judy also came from a good-sized family: She was one of six children in hers. She was a stay-at-home mom, a full-time job by itself.

Before Darrell was born, Judy had been told by doctors that she couldn’t get pregnant again, so his arrival was a pleasant surprise. The Mays moved to Oregon nine months after Darrell was born, settling in Rogue River next door to his maternal grandparents and his mother’s sister. His father had fallen in love with the area, which reminded him of his home state West Virginia; and being near family was a plus.

The family lived on 10 acres of land in the natural beauty of southern Oregon, with plenty of room for baseball. Jeff was a very good basketball player, and Darrell wanted to follow in his footsteps. But Darrell suffered from asthma, and in his first day of practice in seventh grade, his asthma was so bad he couldn’t run up and down the court one time without needing his inhaler. After a few days of that, it was apparent that Darrell would need to find another sport. Wrestling took over his fall and winter sports schedule, with baseball remaining his spring and summer sport.

In Oregon the May family became acquainted with another Southern California import, John “Buzzy” Black (“I remember hearing one time that he could never sit still, so he got the nickname Buzzy,” May said.1)

Black had coached Little League baseball for decades in Southern California, and when he saw 10-year-old Darrell’s potential, he decided it was time to get back into coaching. Black would guide May throughout high school, and even when May was in the majors, Black would analyze video of his pupil and send him suggestions.

After graduating from Rogue River High School, May headed back to California for his college education. He attended Sacramento City College, excited at the chance to play for coach Jerry Weinstein, who was in the middle of a career that would see him win 830 games and a national title at the school.2 At first, Sacramento City College was not in May’s plans, but some Rogue River High School alumni who were friends with Black pushed for May to go there. On his way to a recruiting visit to Taft Community College in California, May stopped and threw a bullpen session for Weinstein, whose interest was piqued.

“After talking with him and the coaches and looking at all his memorabilia in his office and the guys who have been through that program, I didn’t look anywhere else. I knew that’s where I was going,” May said.

The Oakland Athletics, with Dave Wilder scouting him, selected May after his freshman year, in the 14th round of the June 1991 draft. Despite his high-school success, May had not been scouted, so the lure of professional baseball was strong. But May decided to continue his education for one more year at least. Under the rules at the time, the Athletics retained his draft rights until the 1992 draft. As that draft neared, May was committed to the University of Tennessee. When Oakland contacted him again in a last-ditch effort to sign him, Wilder had moved on to Atlanta. May’s new contact with Oakland insisted that the team’s offer was a lower number than May remembered. May called Wilder on the second day of the 1992 draft, mainly out of curiosity over which offer was correct. Once Wilder realized May was available, he persuaded the Braves to draft him, with a better offer than Oakland had presented despite the lower draft position.

Atlanta was becoming famous for its ability to develop pitchers as an organization, with names like Tom Glavine, Steve Avery, Kent Mercker, Mike Stanton, and Mark Wohlers leading the Braves’ renaissance in the early 1990s. That was an enticement to sign with the Braves, as was the team’s offer to pay for May to continue his college education.

“To this day, if anybody asks, ‘what was your favorite organization?’… Braves, definitely,” May said. “I saw how consistent it was at every level. Every coach teaches differently, but what they taught and how they taught, from Single A to Double A to Triple A, it was going to be the same.”

May’s first day of professional baseball was his 20th birthday. Despite his low draft position (or perhaps unburdened by not being highly drafted), May progressed steadily through the Braves system. All along the way, he showed an ability to throw strikes, with 2.22 walks per nine innings for his minor-league stops from 1992 to 1995.

All of that got him to the doorstep of the major leagues. By the time rosters expanded in September 1995, the Braves had a healthy lead in the NL East and were looking to the postseason. When Mercker tweaked his back, Atlanta summoned May to the majors, with Richmond manager Grady Little delivering the news to him after May had pitched 4⅔ no-hit innings in a game that was eventually rained out in Richmond’s last series of the year.

“He asked me at the end of the game if I was riding the bus back or driving (from Norfolk to Richmond). I said I was riding the bus. He said, ‘Well, don’t be late.’ I remember I was pissed off because I prided myself on being early. I did not ever want to be late, I didn’t want to be the guy other guys were waiting on, so I was like, ‘Why did he say that, did he see me late or something?’ Well, the reason he didn’t want me to be late was because he had to tell me I was getting called up to the big leagues. So we got back to Richmond, he calls me into his office. I thought, ‘Oh no, what’s going on?’ He goes, ‘I hate to inform this to you, but Kent Mercker hurt his back. You’re going up.’ I was like, ‘What?!?’ I kind of thought I had hit my plateau in this organization because of the studs we had at the big-league level,” May said.

May made his major-league debut on September 10. With a 17-game lead in the division and 19 games left to play, the Braves were already setting up their playoff rotation. So Maddux started but pitched only one inning. He was followed by Jason Schmidt for three innings. May entered the game to pitch the bottom of the fifth with Atlanta ahead, 4-2. He allowed a single to Greg Colbrunn, then got a fly out and two grounders to end the inning. His second inning of work was a little rougher, as Quilvio Veras led off with a bunt single, then stole second and third. He scored on a sacrifice fly, but May recovered nicely to work through the heart of the Florida order, giving up a single to Jeff Conine but getting fly balls from Gary Sheffield and Terry Pendleton. Ultimately, the Marlins scored an unearned run in the ninth and then got the winning run in the 11th for a 5-4 win, but it was still a successful debut for May.

May pitched in one more game in 1995, two nights later in Colorado. This outing was uglier, as the Rockies scored four runs on five hits in his second inning of work en route to a 12-2 win. However, he did notch his first strikeout in the big leagues, getting Vinny Castilla on a swing and miss to end the inning.

For a young pitcher, joining the 1995 Braves was intimidating. But it was also educational, with the chance to study three eventual Hall of Famers (Glavine, John Smoltz, and Greg Maddux) up close.

“They were very welcoming. They would ride you, they would be hard on you. They were intimidating in their card games, playing hearts in the locker room with those guys. You get on one of the guys or give them a bunch of points and he’ll ride you a little bit, but on the slope everybody was very professional, take care of business, let you take care of your business, do your own thing. Well, those guys did their own thing. I did what (pitching coach) Leo Mazzone told me.”

As a rookie and a quiet personality, May mostly tried to absorb lessons from that trio by watching, but would occasionally ask questions. As a left-hander without overpowering stuff, Glavine in particular was a role model.

Those two games in 1995 would be May’s only appearances in a Braves uniform. In 1996, at the end of spring training, Atlanta tried to sneak him through waivers, as he was out of options. Pittsburgh claimed him on waivers. He posted a 7-6 mark for their Triple-A team in Calgary, and appeared in five games at the major-league level before being waived by the Pirates. The California Angels claimed him in September, and he broke camp with the major-league team in 1997. He had pitched sparingly when he was demoted to Triple-A Vancouver in mid-May, but came back up in mid-July and pitched well in a long-relief role: a 3.86 ERA in 23⅓ innings before a rough September. Still, he seemed to be in the Angels’ plans for 1998.

Until the end of spring training, anyway. Despite assurances that he would be the fifth starter, despite working with Angels pitching coach Marcel Lachemann over the winter, and despite a good spring training, May once again fell victim to a numbers game.

“I was told, whether it was true or not, they had signed a couple guys to guaranteed contracts. They weren’t doing well at all, but they were guaranteed contracts. They were going to keep them,” May said.

The Angels kept May on the roster until the end of spring training, hoping to sneak him through waivers. In the meantime, the Hanshin Tigers of the Japan Central League were interested. They had actually been scouting May for a while but the Angels had been unwilling to sell May to them.

“As a kid, I didn’t grow up wanting to play baseball in Japan. I didn’t want to meet with them. My agent had to talk me into meeting with them, just to hear them out. We met with them. … I was blown away with how much money they were willing to pay a guy that had, I think, maybe one year of big-league experience under my belt,” May said.

The money was persuasive, as May figured he could help his family and still come back to the United States and try his luck with a minor-league team. Despite some trepidation, May signed a two-year deal with Hanshin.

“I didn’t want a two-year contract, because if I didn’t like it, I didn’t want to have to come back for a second year. They convinced me they don’t sign any foreigners to less than two-year deals,” May said.

But May discovered that of six foreign players in the organization, he was one of only two signed for more than one year. He stuck with it, though. May seemed to do particularly well against the Yomiuri Giants, who have a fierce rivalry with Hanshin. So when May’s two years with Hanshin were done, the Giants must have taken some delight in signing him as a free agent. After a successful 2000 season that included May finishing third in the league in strikeouts, he signed with Yomiuri for one more season.

Looking back, May said he enjoyed his time in Japan much more than he expected he would when he signed with Hanshin. Japanese teams pay for players’ apartments, so while he was making more money than he had in major-league baseball, he was also able to save more. The cultural differences were eventually overcome, as well.

“You think baseball is baseball, but it’s completely different over there. Once the game starts, there’s a lot of similarities. Most people wouldn’t notice the differences but being there and playing it, you definitely see the difference. Once I learned some of the language and adjusted to their style of baseball, I had a lot more fun with it and I really enjoyed playing in Tokyo,” May said.

During that 2001 season, Allard Baird, then general manager of the Kansas City Royals, began scouting some Japanese players and noticed May. Baird was impressed with May’s poise and command.

“The thing was not only what we saw on the field but the Giants over there are like the New York Yankees and are playing before about 45,000 people every night. So here’s a guy who came over from the States, is playing for their big-market team and that’s added pressure,” Baird said.3

Meanwhile, May credited his time in Japan with preparing him to be in a major-league rotation.

“I needed to develop my breaking ball and, in Japan, they’re good breaking-ball hitters. I talked to a lot of coaches who said you’ve got an average fastball and you’ve got to hit your spots,” he said.4

May’s 2002 got off to a rocky start, as he started the season on the disabled list with a torn groin. In his first game back, he re-injured it. It wasn’t until June 6 that he picked up his first big league win in five years, pitching five innings in Kansas City’s 4-3 win over the Chicago White Sox.

The 2002 Royals were in turmoil. Contraction rumors swirled early in the season before word came that the Royals were not a candidate. Manager Tony Muser was fired in late April, followed by pitching coach Al Nipper in June. The team became the first 100-game loser in franchise history.

All of which made 2003 that much sweeter for May and the Royals. The team jumped out to a 16-3 start, which stunned everybody outside the locker room. They reached the All-Star break with a seven-game lead in the American League Central Division. But Minnesota caught fire in the second half and captured the division title. Kansas City still ended up with an 83-79 record, the franchise’s first winning mark since the strike-interrupted 1994 season.

Those facts obscure the almost comical lengths (such as signing Jose Lima, without scouting him first, out of an independent league and sticking him in the rotation) Baird had to go to in order to round out the pitching staff. Nearly every pitcher on the Opening Day roster was hurt at some point, as the Royals used a whopping 29 pitchers, 15 of whom made at least one start. May took the ball a team-high 32 times. (Chris George and Jeremy Affeldt tied for second with 18 games started.) And he would have taken it more often.

“I was trying to talk them into giving me the ball every four days, coming from the Braves organization where we threw two bullpens between starts. There were times where they put me in the bullpen between starts because they knew I was used to it,” May said.

Of all those pitchers, May was the only one to reach double digits in wins. He also led the team in innings pitched, ERA, and strikeouts. As the veteran of the season-starting rotation (the only one older than 24), May did everything they could ask of him and was given the team’s pitcher-of-the-year award at season’s end.

Expectations were high for the 2004 Royals. But after a walk-off win over the White Sox on Opening Day, things fell apart quickly. May stayed dependable, making a team-high 31 starts. But while 2003 was a storybook season, this was a nightmare. Despite pitching for a team on its way to 104 losses, May’s record was 9-12 in mid-August. Then he took six losses in a row; the Royals were shut out in the last three. With three turns left in the rotation, May had a chance to lose 20 games. Detroit’s Mike Maroth had been saddled with 20 losses the previous season, but Brian Kingman of the Oakland A’s was the last pitcher before him to do so, in 1980. A stigma had grown around the number.

A frustrated May said, “You try to keep in perspective. I can’t put the blame on anybody else. But, realistically, I know there are a lot of games that easily could have gone the other way. Let’s put it this way: There are a lot of games where I felt like I did my job that ended up as losses.”5

As it was, May ended up with a league-leading 19 losses. The Royals were looking ahead to next season and had switched to a six-man rotation, so May’s start on September 28, a 5-1 loss to Cleveland in game 157, was his last of the year. It was also his last appearance in a Royals uniform. On November 8, 2004, he was traded to San Diego with relief pitcher Ryan Bukvich for outfielder Terrence Long, pitcher Dennis Tankersley, and cash.

May’s time in San Diego was brief. After just 22 appearances, he was traded to the New York Yankees with pitcher Tim Redding and cash for relief pitcher Paul Quantrill. May appeared in just two games for the Yankees, making his final appearance on July 15. He finished the season at Triple-A Columbus, then latched on with the Minnesota Twins as a free agent.

May’s role in Minnesota was to serve as a fifth starter until prospect Francisco Liriano was ready to step in. During spring training, it became apparent the youngster was ready.

“He went into spring training and just dealt. It was fun to watch. He had the nastiest slider I think I’ve ever seen from a lefty other than Randy Johnson. So I understood why they took him,” May said.

May caught on with Cincinnati, pitching at Triple-A Louisville. But with a wife and two young daughters growing up quickly, he was already contemplating retirement. When his younger daughter, who had not seen him in a month and a half, didn’t recognize him, he knew it was time.

In retirement, May was coaching some high-school and small-college baseball in the Austin, Texas, area. He was also giving lessons. One student showed some promise, and May told his parents they would need to think about agents someday soon. May called his former agent, Paul Cohen, and that led to an offer for May to work with Cohen’s agency. From his home base in Austin, he was put in charge of recruiting players in Texas for the agency. As opposed to coaching or scouting, the job allowed him to spend more time at home with wife Heather (the pair were married in 2000) and daughters Grace and Brynley.

Last revised: February 11, 2021

Sources

The author is extremely grateful to Darrell May for agreeing to a phone interview, conducted on August 2, 2019.

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed the Kansas City Star, Baseball-reference.com, and Sccpanthers.com.

Notes

1 Telephone interview with Darrell May, August 2, 2019. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from May are from this interview.

2 All-Time Win/Loss Record, sccpanthers.com/sports/bsb/all_time_win_loss, accessed August 17, 2019.

3 Dick Kaegel, “May Took Indirect Route to KC,” Kansas City Star, February 20, 2002.

4 Dick Kaegel, “May Day Finally Arrives for First Time Since 1997,” Kansas City Star, June 7, 2002.

5 Bob Dutton, “Dreaded 20 Would Put May at a Loss,” Kansas City Star, September 12, 2004.

Full Name

Darrell Kevin May

Born

June 13, 1972 at San Bernardino, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.