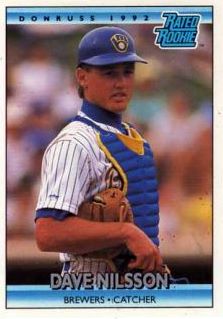

Dave Nilsson

Dave Nilsson is Australia’s number-one batting hero. In 1992, he became the second big-leaguer trained Down Under; through the end of the 2011 season, 25 more of his countrymen had followed him. That group started with Australia’s best-remembered pitcher, Graeme Lloyd. Nilsson and Lloyd formed the first all-Aussie battery in the majors with the Milwaukee Brewers on April 14, 1993.

Dave Nilsson is Australia’s number-one batting hero. In 1992, he became the second big-leaguer trained Down Under; through the end of the 2011 season, 25 more of his countrymen had followed him. That group started with Australia’s best-remembered pitcher, Graeme Lloyd. Nilsson and Lloyd formed the first all-Aussie battery in the majors with the Milwaukee Brewers on April 14, 1993.

The sample of Aussie batsmen is quite small: eight out of 27 major-leaguers. So far only two have come to the plate 1,000 times or more in the majors: Nilsson and the man who preceded him, Craig Shipley.1 Shipley was a useful reserve, but Nilsson emerged as a strong starter in his eight seasons, all with the Brewers. Battling through an array of injuries, he played in 837 games – primarily at catcher, but also frequently in the outfield, at first base, and as designated hitter. He hit .284 with 105 home runs, 470 RBIs, and an OPS of .817.

What’s more, “Dingo” has been a staunch supporter of Australian baseball in many ways. He could have continued his big-league career after the 1999 season but chose instead to represent his homeland in the 2000 Olympics at Sydney. He played in the Australian Baseball League during eight seasons – America’s winter is Australia’s summer – from 1989 through 1997. Digging deep into his own bank account, he sought to keep the circuit afloat as majority owner in 1999-2002. In more recent years he has been a coach and manager.

David Wayne Nilsson was born on December 14, 1969, in Brisbane, the capital of Queensland state. Ten years before, his father, Tim Nilsson, had started Bros Nilsson Printco. The Nilsson family – with Dave at the reins – continues to own and operate this printing firm in the Brisbane suburb of Geebung.2 Dave was the fourth of Tim and Pat Nilsson’s four sons.

Various other members of the Nilsson family have also played pro baseball. Dave’s brother Bob signed with the Cincinnati Reds organization in 1978, becoming one of the earlier Australian pros, though he was released before he ever got into a game. Another brother, Gary, pitched for a Detroit Tigers farm club in Class A in 1984. He appeared in nine games but quit because of an injured shoulder.3 Bob and Gary played extensively in the Australian Baseball League, and the other brother, Ron, pitched there briefly too. In the 2000s, two of Dave’s nephews – Mitch (son of Gary) and Jay (son of Bob) – went on to play in the U.S. too.

Tim Nilsson sparked the clan’s interest. When he died in 2010, the Brisbane North Baseball website described him as “a great stalwart in the development of baseball in this state.” He was a member of the Redcliffe Padres club and served as a junior coach and groundskeeper too.4

It would be interesting to know how Tim originally came to the sport. The closest available clue comes from a 2000 feature by Lisa Olson in the New York Daily News, which said, “Tim Nilsson was a pitcher for Australia in the 1960s, when baseball was that crazy game American sailors played during bouts of shore leave Down Under. Tim gave Dave his first glove and bat when he was four, taught him how to swing at balls that hadn’t bounced first like they do in cricket, and how to run around a diamond rather than the straight line of a cricket pitch.”5

Young Dave’s Under 12 state representative coach, Reg Baxter, remembered “that there was something special about Nilsson: ‘He was a porky little bloke with bow legs and three foot two high, but chocker block full of confidence. You could see he was going to make it because he had the determination.’”6

Nilsson grew to 6’3” and 185 pounds as a teenager; over time he added 30-40 more pounds of mass to his big frame. In 2011, Australian baseball author Nicholas R.W. Henning wrote, “Dave had the physique of a high performance athlete. When you combine Dave’s family influence and his physical attributes, this set the foundations for a talented player. But it is important to remember that Australian athletes with similar physical attributes to Dave often choose other sports ahead of baseball. Rugby league, rugby union, and Australian Rules Football are the sporting pathways that many athletes take in Australia. So with baseball behind these sports in terms of participation, baseball was lucky to secure an athlete of Dave’s prowess. . . it is rare in Australia to have a family that has such a strong disposition towards baseball.”7 It’s not surprising that the same was true of Craig Shipley, whose father and brothers were all players as well. But Dave’s mother Pat was even scorekeeper for the state team, the Queensland Rams!8

Nilsson moved up through the youth ranks in Queensland. During the summer of 1986, the teenager – who then played mainly first base – came with the Rams to tour the United States. He stayed on to play for three weeks with the Park Ridge (Illinois) Orioles, a semi-pro team. The young Aussie caught the eye of Milwaukee scouts Kevin Greatrex and Bill Castro, who recommended him.9 Greatrex bears mention as one of the first two Australian pros to play in the U.S. He and Dick Shirt were both in the Cincinnati Reds chain in 1967.10

On January 28, 1987, the Brewers signed Dave as an amateur free agent. Reports of the bonus he received ranged from US$10,000 to US$65,000.11 Dan Duquette, the future general manager of the Montreal Expos and Boston Red Sox, was at that time Milwaukee’s scouting director. Duquette said, “He was just 16 then [the previous summer] and was playing against guys 24-25. He has a good arm and is a natural left-handed hitter with some power. David’s amateur background is limited, but we think we have a chance to make him into a player. And, he can go back to Australia in the winter and play.”12

Shortly after he signed with the Brewers, Nilsson and the Queensland Rams won the finals of Australia’s national baseball championship, the Claxton Shield.13 After going to extended spring training, Nilsson went to Helena of the Pioneer Rookie League, where he hit .394 in 55 games. He had not yet developed his power, hitting only one home run. At that point in his career, he was still a switch-hitter. In fact, as late as 1993, his baseball cards still described him as batting from both sides, though baseball references say that he swung only lefty as a big-leaguer. From the beginning, the Milwaukee organization put him at catcher.

After undergoing the first of many knee operations, Nilsson – winner of Australia’s national batting award – was not available for the 1988 Claxton Shield finals.14 The Brewers moved him up to Beloit in the Class A Midwest League that spring, and he went through an adjustment, batting just .223 with 4 homers and 41 RBIs.

Nilsson spent the summers of 1988 and 1989 with Stockton of the California League (high Class A). His batting lines improved to .244-5-56 and .290-7-47, and he also won praise for his defense. Milwaukee Sentinel baseball columnist Tom Haudricourt wrote that after seeing Nilsson at Beloit and in Stockton the first year, “the Brewers weren’t sure if they had a big-league prospect or a mere novelty.” But in 1991, Tom Trebelhorn, manager of the big club, said, “He has matured nicely physically, and also as a player. He has shown tremendous improvement.” Coach Andy Etchebarren, the former big-league catcher, added, “No question about it, he’s a legitimate prospect. Not just a chance prospect, but a legitimate one. He listens and works hard – that’s how he has made improvement.”15

During the winter of 1989-90, Nilsson played for the Gold Coast Clippers in the newly formed Australian Baseball League (.277-2-11 in 34 games). In the 1990-91 ABL season, the Clippers became the Daikyo Dolphins after a Japanese real estate firm invested in the franchise as part of its extensive Gold Coast leisure portfolio. Nilsson took a big step forward, batting .400-12-37 in 40 games. He was named to the league All-Star team at catcher and won the MVP Award; Daikyo finished 31-9, best in the league.

The Aussie climbed to Double A in 1991, and he hit a blistering .418-5-57 in 65 games for El Paso of the Texas League. He earned promotion to Triple-A Denver, where he cooled off (.232-1-14 in 28 games). Even so, he was in line for his first call-up to the majors, but in August he underwent season-ending surgery on his left (non-throwing) shoulder.16 He made it back for 20 games with Daikyo, batting .403-2-13 and helping the Dolphins win the ABL title (they had lost in the playoffs the year before).

Nilsson made it to the big club after backup catcher Andy Allanson injured his thigh in May 1992. His debut came at old Tiger Stadium in Detroit on May 18. The Brewers trounced the Tigers, 9-1, and Nilsson’s bases-clearing double in the eighth inning off Kevin Ritz closed out the scoring. Even after Allanson returned, Milwaukee was reluctant to send Dave back to Denver. They finally did so in July, though, but only on a rehab assignment after he went on the disabled list with an injured wrist. He returned in mid-August and finished out the season with the Brewers. Overall, he hit .232-4-25 in 51 games.

In 1993, the Brewers moved their starting catcher for the previous several years, B.J. Surhoff, to third base. Nilsson, who needed wrist surgery in February, had played in just 10 ABL games. Making a rapid recovery, he spent most of the season as Milwaukee’s catcher. On April 14 that year, he caught Graeme Lloyd for the first time in a major-league game as Lloyd came on in the ninth inning of a blowout loss to the California Angels. “It wasn’t a real great moment, was it?” Nilsson said. “I’m just ashamed that it happened in a game like that. I just wished it would have happened in a better game.”17

Nilsson hurt his shoulder sliding in May, and after he got off the DL, he went down to Triple-A New Orleans until mid-June on another injury rehab assignment. In 100 games for the Brewers, he hit .257-7-40. He appeared in 27 more minor-league games during 1995, 1996, and 1998, but those were also rehab stints.

For the 1993-94 ABL season, Nilsson joined the Brisbane Bandits. He had a very strong season (.362-12-47 in 57 games) and helped his hometown team knock off the Sydney Blues for the league championship.18 That action took place after spring training had started, showing that the Brewers were willing to give him some slack.

During the strike-shortened 1994 season, Nilsson hit .275-12-69 in 109 games. From June 8, when he partially tore a ligament in his thumb, until July 19, Dave could serve only as DH. He convinced the team doctors that he could swing the bat and stayed out of a cast, although he had to wear a protective splint whenever he got on base. He said, “I must say I’m concentrating on the ball a lot more. It’s hard to explain. I can’t really wrap my thumb around the bat. I just wrap my fingers around it and keep my thumb away from the bat.” After Nilsson’s grand slam on June 17 highlighted an 8-1 win over the Yankees, teammate Greg Vaughn said, “I’m going to go slam my thumb in the door.”19

After the strike halted play, Dave returned to Australia, signing what the Milwaukee Sentinel described as a “lifetime contract” with the Waverly Reds of Melbourne, in which he received a 25 percent equity stake in the club. His mission also included development of junior players and promotion of the sport in general.20 Nilsson played 54 games in the ABL 1994-95 season, and it was probably his most impressive overall there (.388-16-56).

At home, however, he contracted Ross River Fever, a rare mosquito-borne viral illness endemic to Australia and other nearby islands in the Pacific. The hallmark of the draining disease is joint pain, and it typically takes weeks to recover. Nilsson did not appear for the Brewers in 1995 until June 24. He batted .278 in 81 games, and his half-season homer and RBI totals (12 and 53) might have projected as his best if he’d been able to play all year. To conserve his energy, however, he only played two games behind the plate that season.

Owing to a dispute with his ABL team (which had changed its name to the Melbourne Reds), Nilsson played in just 11 games before coming to spring training in 1996. There, veteran Chicago baseball writer Jerome Holtzman wrote a feature on the emerging young slugger, describing his hitting style. “Nilsson hits out of a straight-up stance, parallel to the plate, with a solid setup. He has a short stroke, has power to all fields and appears to have good discipline. But, like most young players, when he goes into a slump he starts to overswing. Once he conquers this fault, he should put 20 to 25 points on his batting average.”21

He did that and more: Nilsson hit .331 for the Brewers in 123 games in 1996, finishing sixth in the American League. He hit 17 homers and drove in 84. Again he missed a portion of the season; this time a stress fracture in his left foot, sustained in spring training, meant that he made only one early-season appearance before going on the DL. He did not return until May 9. On May 17, he hit two homers in a game for the first time in the majors – in fact, he did it twice in the same inning at Minnesota’s Metrodome. He followed up with two more the very next night. The feat was one he accomplished nine more times in the majors.

Nilsson returned to the Brisbane Bandits for the ABL’s 1996-97 season, becoming player-manager. He hit .420 in 16 games before arthroscopic knee surgery cut his on-field action short, but he led his team to the finals.

In 1997, Nilsson signed a three-year contract for $10.8 million. He played a lot of first base, especially after John Jaha (who had been a teammate in the ABL too) hurt his shoulder and was lost for the year. He also saw plenty of action at DH and hit .278-20-81 in 156 games. That was a career high, as was his 629 plate appearances – it was the first time he’d stayed off the DL since 1994. During August he decided not to return to the ABL; instead, his goal was to spend most of his time in Milwaukee working on conditioning.22

That off-season, Dave wound up having knee surgery, and his recovery was slow. He spent most of spring training rehabbing the knee, and only about a week after he returned to action in March, he had to have it scoped. He was out until May and had a disappointing year by his standards: .269-12-56 in 102 games.

Probably the most interesting development of 1998 for Nilsson came on Christmas Eve. He decided to put up US$3.5 million of his own money to buy majority ownership of the struggling Australian Baseball League. Although American players were to be allowed, he wanted to focus on his young countrymen. Dave said, “The players there are good enough that unless there are very good pro players coming over, we don’t want to take away a spot. Pros won’t take the place of local kids.”23 As of March 1999, Nilsson was planning to add teams from Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.24 Indeed, the circuit was renamed the International Baseball League of Australia.

Despite his knee issues, Nilsson moved back to catcher in 1999, after having played just 15 games there from 1995 through 1998. He set his career high in home runs, hitting 21 in just 115 games to go with a .309 average and 62 RBIs. That year he was named to the All-Star team for the first time; he struck out against John Wetteland in his only at-bat. As of the 2011 season, he remained the only Australian All-Star ever. Near the end of August, Dave suffered a broken thumb when struck by a foul tip.25 He returned for three games at the tail end of the season, but those were his last in the majors.

A big subplot to the 1999 season and beyond concerned the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney. Back in 1993, the International Olympic Committee had awarded the XXVII Olympiad to the “Harbour City.” At some point, though even his family thought it was quixotic, Nilsson began to think about what it would be like to represent his nation. As Lisa Olson wrote, “Nilsson’s patriotic buzz kicked in. If he stayed with the Brewers, he would have been ineligible for the Olympics, since MLB insisted on making this strictly a minor-league affair.”26 The Olympic baseball steering committee co-chairman was former big-leaguer and Yankees executive Bob Watson. In August 2000, Watson said, “I don’t see anybody here giving up players [during the season].”27

In November 1999, shortly after Nilsson became a free agent, the IBAF Intercontinental Cup took place in Sydney. The host nation knocked off heavily favored Cuba in the final of the eight-team tournament; with 12 RBIs, Nilsson was named MVP and all-star catcher.28

Then in January 2000, after talking with a number of big-league teams, he signed a one-year deal for $2 million with a Japanese club, the Chunichi Dragons of the Central League. His agent, Alan Nero, said, “Chunichi was very aggressive in its approach, and made the opportunity available for him to play in the Olympics.” Another sweetener was a three-year working agreement that the Dragons signed with the Australian Baseball League, which Nilsson had previously bought. “Building a bridge from Japan to Australia was an important part of this,” Nilsson said.29

While in Japan, Nilsson chose to wear the nickname “Dingo” on his jersey. 30 In fact, Nilsson was the first Australian to play there – but his experience didn’t go well; he hit just .180-1-8 in 18 games for Chunichi in 2000. “We have very high expectations of him,” Chunichi president Tsuyoshi Sato had said when Nilsson signed – that’s something gaijin (foreign) players often experience in Japan. That June and in 2008, Wayne Graczyk of the Japan Times described various other things that made the season go “completely haywire.”

Nilsson “was told he would play left field exclusively, as the Central League has no DH system.” Then out of the blue, in the middle of an exhibition game, manager Senichi Hoshino called him in out of left and put him behind the plate. “I had no clue what was going on,” he said. “I had no preparation, didn’t know how to communicate with the (Japanese) pitcher, what pitches he threw or what signals to call for.”31

The tough adjustment spilled over to Dingo’s mindset at the plate. After 15 games, the Dragons sent him to their farm club in the Western League, where his batting picked up – but then a painful lower-back condition sent him home to Australia for treatment. He was able to return for just three more games; the roster limit of two non-Japanese position players was another factor.32 The Dragons sent him to the minors for a second time in August, then granted him his release so he could head home to Australia.33

The Olympic baseball tournament was held from September 17-27, 2000. A few days before it started, Nilsson said, “Let me clarify that I haven’t made one sacrifice to come.”34 He then proceeded to give an outstanding performance. Australia went just 2-5, finishing seventh, ahead of only South Africa – but Nilsson led all batters with his .565 average (the runner-up was Cuba’s Antonio Pacheco at .450). He was 13 for 23 with six doubles and a homer, so his slugging percentage of .957 was also tops. He finished in the top ten in every offensive category and even stole three bases, equaling his single-season high in the majors.35

Following the Olympics, at least four teams, including the New York Yankees, expressed interest in signing Nilsson.36 The Red Sox – where Dan Duquette was then general manager – were keenest. Reportedly they were willing to offer $10 million over two years.37 Boston withdrew the offer, though, after Nilsson failed a physical because of chronic problems with his left knee.38

Meanwhile, the International Baseball League of Australia never achieved success, let alone the scope that Nilsson originally envisaged. Six teams, all Australian, played a limited 17-game schedule in 1999-2000. The 2000-01 season featured only a four-team development league, including an international squad, one from Taiwan, and an “MLB All-Star” squad (most likely minor-leaguers). The interstate Australian format of the Claxton Shield returned for 2001-02, and after that the IBLA collapsed.

As author George Gmelch wrote in his book Baseball without Borders, problems had arisen early in 1999, almost as soon as Nilsson had bought in. “Several weeks after the agreement and media releases, the ABL owners pulled out of the deal. This turn of events not only ended all the euphoria over the new national league but killed any chance of another national league for Australian baseball. According to Nilsson the ABL wanted to go along with the new deal, but the owners were unhappy when they realized that Nilsson $5,000,000 purchasing fee [Australian dollars] would not be used to assume their substantial debts.

“With small crowds and hefty expenses the teams soon floundered. Cost-cutting, lack of funds, and decreased services were apparent in all venues. Home runs were rare with the use of wooden bats. Media coverage was limited.”39

After a two-year break from playing, Nilsson agreed to a minor-league deal for $400,000 with the Red Sox in January 2003. It came “at the urging of another fellow Australian, Jon Deeble, the Pacific Rim scouting director for the Sox.” Another good friend from back home, Craig Shipley, was also instrumental in the decision.40 Shipley had joined the Boston organization the previous November as special assistant to GM Theo Epstein. In mid-February, however, Nilsson phoned Shipley to say that he had decided against playing.41

Nilsson managed his old club, the Queensland Rams, in the 2003 Claxton Shield, and they won the championship. He returned to the field that year for Telemarket Rimini in Italy’s Serie A1.

Aged 34, Nilsson was back with Team Australia for the 2004 Olympics in Athens, Greece. That January, he told the Sydney Morning Herald, “It’s good to get out there again playing with all the young guys. I made a decision this year to play in the Olympics and I’m just trying to get the body back in shape. The 2000 Olympics were a big disappointment. A lot of things went wrong with the program but when you look back now and see all the areas where we went wrong, you know that this time we’ll do things differently and the right way.”

“Can we win a medal in Athens? Yeah. If we don’t win a medal, it will be more disappointing than Sydney. It doesn’t matter if we get our players back from the majors . . . We have enough depth in this country.”42

As part of getting back in shape, Nilsson played in the Australian season for the first time in several years, taking part in the 2004 Claxton Shield. He was still mourning the loss of the ABL, saying, “From a player’s point of view, it was a platform where you could play your 50 games every year, improve your game and give the young kids coming through something to aspire to. That’s where we really miss it. For the young kids, the focus right now is totally in America, so that’s unfortunate.” Yet he was philosophical too, adding, “Having the Claxton Shield gives players a place where we can play against each other at a top level, and that’s all we have right now, and we have to make the most of it and not worry about the . . . past. The Claxton Shield is also a great opportunity for the players to prepare and push for selection in the Olympic squad.”43

Following the Shield competition, Nilsson gave U.S. ball another shot, signing as a free agent with the Atlanta Braves. He got into 16 games with Atlanta’s top farm club, Richmond, hitting .236 in 55 at-bats with a homer and 4 RBIs. He strained an oblique muscle in May, however, and after missing three weeks with the injury, he abandoned his pro comeback.44

In August, however, captain Nilsson helped his squad achieve their goal of a medal. Managed by Jon Deeble, the Aussies took silver behind Cuba after upsetting Japan’s “Dream Team” 1-0 in the semi-final. Nilsson’s walk was part of the run that Australia scratched out against Daisuke Matsuzaka, who struck out 13 in seven innings. The Sydney Morning Herald called it “the most monumental moment in Australian baseball history.”45 Dave batted .296 in the tournament’s eight games.

Nilsson was minor-league catching coordinator for the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2005 .46 His last playing appearances came for Australia in the 2006 World Baseball Classic (he went 0 for 5 with a strikeout).

In 2006, Nilsson became chief hitting instructor for the Major League Baseball Australian Academy Program. He moved up to head coach in 2007.47 But when a new Australian Baseball League formed in 2010, Nilsson jumped at the opportunity to manage the revived Brisbane Bandits. That August, the Queensland Courier-Mail carried a jolly photo of the Nilsson family – Dave, wife Amanda, and children Tyla, Ashlee, Grace, Elijah, and Jacob – as he talked about the new six-team circuit.

“It was a no-brainer,” Nilsson said. “I love being involved in baseball and with the new league and the opportunity to come back to Brisbane and be a part of the Bandits organisation didn’t require much thought. I’m excited for the baseball community of Brisbane and Queensland. There’s something now for the young kids coming through to follow and learn from.”48

He also talked about the need for the latest incarnation of the ABL to find financial sustainability and learn from the mistakes of the past. “It’s about making wise decisions. Ensuring the financial structures are solid. Every sport in Australia has undergone dramatic changes since the 1990s and our sport is the last one. It is a different world now and we understand that,” he said.49

There was even some talk that Nilsson might return to active play, but he told the Sydney Morning Herald, “I think it’s just good banter. If they [the ABL] were serious about it they would have approached me 12 months ago. . .I’ve got a big family, I’m old, I’m out of shape, I don’t do this for free any more.”50

In October 2011, Nilsson stepped back as manager of the Bandits “to focus on business and family commitments. . .[he] will stay on as a consultant.” Replacing him as skipper was former major-leaguer Kevin Jordan.51

In 2008, Dave Nilsson was named to the Sports Australia Hall of Fame. Nicholas Henning has summed up this athlete’s position in Australian baseball well. “Through years of hard work Nilsson established himself as a genuine power hitter. . . he reached a higher hitting echelon than any other Aussie player has to date. With the new Australian Baseball League entering its second season and a continuous flow of Aussies in professional baseball leagues overseas, there is certainly potential for another player of Dave Nilsson’s calibre. Yet I predict that such a talent can only come once every 20 or so years, as baseball in Australia is in the shadow of so many other sports, but its capacity to grow is certainly encouraging.”52

Last revised: December 19, 2013

Continued thanks to Nicholas R.W. Henning in Australia for his input. Dave Nilsson is frequently mentioned in the second novel by Nicholas, “Boomerang Baseball.”

Sources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

Flintoff, Peter & Adrian Dunn. Australian Major League Baseball: The First Ten Years. Self-published and printed independently: 2000. (Used as a source for Australian Baseball League statistics only.)

http://www.pflintoff.com (more Australian Baseball League historical facts)

www.la84foundation.org (Olympics information)

www.rotoworld.com

http://web.theabl.com.au

http://www.worldbaseballclassic.com/2006/stats/stats.jsp?t=t_ibp&cid=760

1 This list omits 19th-century player Joe Quinn, who moved to Iowa as a boy.

2 Bros Nilsson Printco website (http://www.bnprintco.com.au/about-us). Holtzman, Jerome. “If Brewers Come Out from Down Under, It Might Be Because of Down Under.” Chicago Tribune, February 29, 1996: Sports-3.

3 Peter Gammons, “Australia: Land of Foul Snicks and Safe Hits.” Sports Illustrated, April 18, 1988.

4 http://www.bnr.baseball.com.au/default.asp?Page=72073. http://www.bnr.baseball.com.au/default.asp?Page=72134

5 “Nilsson: No Regrets – Aussie Glad He Chose To Follow Dream.” New York Daily News, September 25, 2000.

6 Joe Clark, A History of Australian Baseball. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003: 90.

7 Nicholas R.W Henning, “Dave Nilsson: Who will be the next?” (http://nicholasrwhenning.blogspot.com/2011/06/dave-nilsson-who-will-be-next.html)

8 Gammons, “Australia: Land of Foul Snicks and Safe Hits”

9 “Brewers sign Australian.” Milwaukee Journal, January 29, 1987: 2-C.

10 Cincinnati signed a pitcher named Neil Page in December 1965. Page, who was reportedly the first Australian to sign a U.S. contract, appears never to have played a game in the minors. “Reds sign Australian.” Associated Press, December 28, 1965.

11 $10K: Richard D Lyons, “Baseball Fever on the Rise in Australia.” New York Times, February 6, 1987. $50K: Gammons, “Australia: Land of Foul Snicks and Safe Hits.” $65K: Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 8, 1987: B-16.

12 Tom Haudricourt, “Brewers sign Aussie.” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 30, 1987: Page 3, Part 2.

13 “Baseball.” The Age (Melbourne, Australia), February 23, 1987: 37.

14 Harvey Silver, “Claxton Shield final is on – again.” The Age, February 23, 1988: 52.

15 Tom Haudricourt, “Catcher from Down Under wants to make it to top.” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 13, 1991: Page 2, Part 2.

16 Tom Haudricourt, “Higuera surgery set.” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 16, 1991.

17 Bob Berghaus, “Nilsson, Doran return after rehabilitation stints.” Milwaukee Journal, April 15, 1993: C6.

18 “Sports People.” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, February 21, 1994.

19 Tom Haudricourt, “Brewers blow out Yankees.” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 18, 1994: 1B.

20 Tom Haudricourt, “Nilsson lending his hand in Australia.” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 29, 1994:

21 Holtzman, “If Brewers Come Out from Down Under, It Might Be Because of Down Under”

22 Drew Olson, “Nilsson to give up sun for snow to shape up.” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, August 16, 1998.

23 “Nilsson a League Owner.” Lakeland (Florida) Ledger, July 14, 1999: C4.

24 John Henderson, “The C word in baseball isn’t curve.” Denver Post, March 14, 1999: C4.

25 “Nilsson injured for rest of season.” Associated Press, August 30, 1999.

26 Olson, “Nilsson to give up sun for snow to shape up”

27 “3 Kentuckians Make Team; Reds’ Prospect Also on U.S. Olympics Squad.” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, August 24, 2000: D1.

28 Mark Shapiro, “Australia Beats Cuba For Intercontinental Cup Baseball Gold.” Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1999.

29 “Sayonara: All-Star Nilsson bound for Sydney via Japan.” Associated Press, January 17, 2000.

30 Wayne Graczyk, “Foreigners have never caught on as backstops in Japan pro ball.” Japan Times, May 18, 2008.

31 Wayne Graczyk, “Dang! There goes Dingo.” Japan Times, June 4, 2000. Graczyk, “Foreigners have never caught on as backstops in Japan pro ball”

32 Graczyk, “Dang! There goes Dingo”

33 “Sydney 2000: First pro tournament has new look, same question.” Associated Press, August 15, 2000.

34 “Nilsson’s set to play at home after long year.” Associated Press, September 14, 2000.

35 Official Report of the XXVII Olympiad: Volume Two – Celebrating the Games. Sydney, Australia: Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games, 2001: 178 (http://www.la84foundation.org/6oic/OfficialReports/2000/2000v2.pdf). Volume 3 – Results. (http://www.la84foundation.org/6oic/OfficialReports/2000/Masters/bb/BBresults.pdf)

36 “A’s Giambi Grabs AL’s MVP Award.” Washington Post, November 16, 2000: D7.

37 Gerry Callahan, “Nilsson rating: Typical Sox.” Boston Herald, November 3, 2000: Sports-9.

38 Sean McAdam, “Free agent Nilsson fails to pass Sox’ physical.” Providence Journal, November 30, 2000.

39 George Gmelch, Baseball without Borders. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2006: 302.

40 Gordon Edes, “Red Sox Closing in on Ortiz, Nilsson.” Boston Globe, January 21, 2003: D8.

41 Bob Hohler, “Nilsson Quits Before Getting Started.” Boston Globe, February 13, 2003: D3.

42 Michael Cowley, “Nilsson shaping up for another shot at an Olympic medal.” Sydney Morning Herald, January 20, 2004.

43 Ibid.

44 Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 30, 2004.

45 Michael Cowley, “Aces of bases: Australia one win from gold.” Sydney Morning Herald, August 25, 2004.

46 Andrew Bagnato, “A Whole New Game.” Arizona Republic, February 27, 2005: C8.

47 Ben Foster, “David Nilsson Named 2007 MLBAAP Head Coach.” MLBAAP website, May 3, 2007 (http://www.mlbaap.baseball.com.au/?Page=35369&MenuID=Archive%2F24625%2F0%2C2007_MLBAAP%2F21131%2F43721%2CNews%2F20088%2F0%2F0)

48 Greg Davis, “Brisbane Bandits nab MLB all-star Dave Nilsson as team manager for the new Australian Baseball League.” Queensland Courier-Mail, August 25, 2010.

49 Ibid.

50 Daniel Lewis, “Right word might have lured nation’s best player from retirement.” Sydney Morning Herald, November 29, 2010.

51 Sean Baumgart, “Nilsson steps back from Bandits job.” Brisbane Times, October 3, 2011.

52 Henning, “Dave Nilsson: Who will be the next?”

Full Name

David Wayne Nilsson

Born

December 14, 1969 at Brisbane, Queensland (Australia)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.