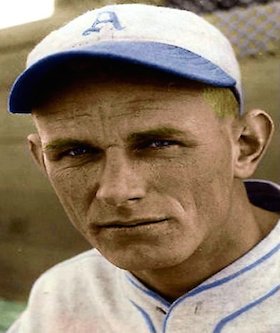

Dib Williams

From the predicted goat to the arguable hero of the 1931 World Series was quite an accomplishment for a somewhat stoic Dib Williams.

From the predicted goat to the arguable hero of the 1931 World Series was quite an accomplishment for a somewhat stoic Dib Williams.

Dr. Earl Williams, an Arkansas country doctor, really enjoyed baseball, and a couple of the players he helped develop made it to the major leagues: Otis Brannan, an infielder for a couple of years with the St. Louis Browns in 1928 and 1929, and Herschel Bennett, who played with the 1923-27 Browns. He helped encourage two of his sons into baseball, too. Dib Williams was an infielder for the Philadelphia Athletics and Boston Red Sox 1930-1935. His older brother Royce played at least eight seasons in the minors but never made it to the big leagues.

It’s his son, Edwin Dibrell Williams, we are focused on here. He was born on January 19, 1910, in Greenbrier, Arkansas, the third child of Laura Glover Williams and Earl T. Williams, a physician described as a “country doctor.”1 At the time of the 1910 census, the family lived in Hardin, Arkansas, but they moved about 75 miles north to Greenbrier. “My father always took an interest in baseball,” Dib later told sportswriter James Isaminger. “He played semipro ball when a boy and then when he went to school. In spite of a wide medical practice stretching many miles around the surrounding country, he found time to direct the little team at Greenbrier. He picked the players and developed them. He coached both my brother and myself from the time we wore short pants and even helped us get placed with teams after we learned a little about the game.”2

Two others from Greenbrier, brothers Fred and Louis Cato, reportedly also made it into the pros at the minor-league level. Isaminger wrote that Greenbrier “boasts of a drug store or two, a cotton gin, Odd Fellows’ Hall, filling station, garage, small-time movie, and about 500 sun-baked natives.”3 Working with the young players, Dr. Williams seems to have made a difference.

Dib Williams went for eight years to the Greenbrier public schools, then to Conway High School in the larger nearby city of Conway. He then went on to higher education. On his player questionnaire for the Hall of Fame, he simply put that he went to Oklahoma State for two years. In a lengthy biography for The Sporting News, Bill Dooly went into a little more detail. He said that Williams had first gone to Hendrix-Henderson College (at Conway) and played some basketball, then to Oklahoma A&M (at Stillwater) where he played football and basketball. But it was baseball he really wanted to pursue, and in January 1929 he left college and told his father that he wanted to be a ballplayer. “Doc Williams lost no time. He immediately went to Little Rock, informed the management there of his son Dib’s declaration and they quickly dispatched a couple of emissaries to sign the lad.”4

He made the team. In fact, Dooly reports, “Dib was something of a sensation at the Little Rock training camp. Though hardly 19 at the time, he had grown to six feet and was strong enough to hit and throw with the best of them. The Travelers started him at first base when the season opened.”5 He is officially listed as one inch short of six feet, weighing 175 pounds. After the first 20 or so games, he was moved to play second base.

With the 1929 Little Rock Travelers, Williams played in 140 Southern Association games, batting .264 with seven home runs. He had attracted the attention of major-league scouts and before the season was over Mike Drennan, representing the Philadelphia Athletics, “grabbed him by outbidding several other big league clubs.”6

He made Connie Mack‘s Athletics in 1930 and served as backup second baseman to Max Bishop, though also playing in 19 games at shortstop. The Athletics won the pennant with a 102-52 record, and the World Series in six games over the St. Louis Cardinals. Williams, still only 20 years old until January 1931, appeared in 67 games and hit for a .262 average (the Athletics as a team hit an impressive .294). He drove in 22 runs and hit his first three home runs, the three-run homer in the July 1 game making all the difference in the 4-1 win over the Tigers.

Both he and utility infielder Eric McNair were ready to help if needed in the World Series. McNair got one at-bat, but Williams was not called upon.

Mack didn’t make many changes for 1931, and it turned out he hadn’t needed to. They won 107 games, and won the pennant again, finishing 13 1/2 games ahead of the second-place New York Yankees. Dib Williams got into more games, 86 of them, 72 at shortstop, bumping up his average a bit to .269 and driving in 40 runs. In July alone, he had a grand slam and a bases-clearing triple. He was 5-for-5 on September 15, in the game the Athletics clinched the pennant.

The Athletics and Cardinals matched up again in the 1931 World Series, this time it going the full seven games and St. Louis coming out on top. Williams played shortstop in every game.

Why was he considered for the goat horns and how did he redeem himself? The argument was advanced by Philadelphia sportswriter Dooly. It’s not that he’d done anything wrong, but all the pundits predicted he would wilt under the pressure of October baseball. Surely Connie Mack would go with the steady, established Joe Boley at short. When he did not, the Cardinals began to think all they needed to do was to hit balls to shortstop. (Williams’ .931 fielding percentage in the regular season was not stellar, and with the added pressure of World Series play, it was not a bad strategy.) “I don’t know of another player who went into a World’s Series under the same demoralizing circumstances,” wrote Dooly.

Right after the Series Mack said, “Williams executed 24 assists and registered seven putouts, without making an error in the Series. Not all the plays were routine; the Associated Press noted his “sensational and errorless” play.7 And he batted .320. Only Jimmie Foxx (.348) and Al Simmons (.333) hit for a higher average among those with more than three at-bats.

He did, though, strike out nine times, and in his piece lionizing Williams, Dooly did not note what the AP did in reporting Game Seven. It was a 4-2 Cardinals win, and the Cards put their first two runs on the board in the bottom of the first inning following back-to-back singles by the first two batters in the order, Andy High and George Watkins. Both singles were Texas Leaguers into shallow left field, and both batters came around to score. The AP game story wrote of the Athletics’ “poor defensive work. Shortstop Dib Williams misjudged two pop flies at the outset….”8 Eddie Collins, writing a column on the final game, declared that Williams “may have committed an error of omission” on one of the two balls, but was “otherwise the outstanding fielding star of the series.”9 John McGraw‘s praise was unqualified, writing that Williams had been “as steady as a rock [while making] a dozen brilliant plays…without anything that even looked like an error.”10

The American League standings flip-flopped in 1932, with the Yankees finishing 13 games ahead of Philadelphia. When Williams struggled in the springtime (batting only .207 by the end of May), Eric McNair took over as starting shortstop for the Athletics, with Williams back in a backup infielder role. He played in 62 games, many more of them at second base than shortstop, hitting a less-productive .251 with 24 RBIs.

When it came to 1933, he re-established himself at shortstop, setting career highs in games played (115), batting (.289, only dropping below .300 in the last week of the season), home runs (11), and RBIs (73). McNair became the backup. The Senators won the pennant; the Athletics finished third.

Sticking with the same players may have started to hurt team performance. It was Connie Mack’s plan again for 1934, though Rabbit Warstler (obtained from the Red Sox as part of the deal that saw Bishop and Lefty Grove go to Boston) played second. The Athletics finished in fifth place and 31 games behind the first-place Detroit Tigers. Dib Williams was hurt early in the year and didn’t take the field in a game until June 8. In August and September, he was back handling the lion’s share of the work at second base. He hit better, in his limited time – .273 in 66 games. He only drove in 17, his lowest total of any year. After the season, he traveled with Connie Mack, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Charlie Gehringer, and others as part of a ball team that visited Hawaii, Shanghai, Manila, and Japan.

There was some talk in January that the Red Sox were talking trade with Philadelphia to bring Williams to them, but Boston GM Eddie Collins scotched the talk.11 He’d gotten off to a slow start in 1935, after a German shepherd bit him in the hand just before the A’s got to Philadelphia from spring training.12 He was 1-for-10 in the early going. Williams was only 24; the Red Sox did see potential there and on May 1, they purchased rights to his contract from Philadelphia. He was to be a utility reserve. His versatility saw him work 30 games at third base, 29 games at second base, 15 at shortstop, and one at first base. He accumulated 283 plate appearances in 75 games. He hit .251 and drove in 25 runs.

Williams battled for a place on the Boston club during spring training 1936 but Jack Kroner won the utility role and Williams was optioned to Syracuse on March 31. Kroner had impressed while Williams had become “extremely uncertain in the field.”13 Williams agreed with the move; he knew his throwing had suffered in 1935 and looked forward to steady work with Syracuse. “After I play every game in Syracuse, I’ll be back in the majors,” he said.14

He played nine more years in the minors, but never got back to the big leagues. After appearing in 40 games for Syracuse, on June 9 he was sent to Little Rock and hit .303 over 90 games there. At baseball’s winter meetings in December 1936, Williams was acquired by Sacramento and for his next four seasons played second base in the Pacific Coast League. He got steady work, playing in between 137 and 177 games a year, averaging around .280, though he was hampered by a number of “injuries and ailments,” so much so that it had been thought his career was over before he seemed to get a second life in 1940.15 In 1940, he’d also worked as a coach and had been voted by the fans as most popular player on the team.16

In December 1937, he married Geneva Martin in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

In 1941, Williams was player/manager of the Class-B Decatur Commodores in the Three-I League (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa), and he hit .342 while playing in 123 games. The Commodores finished third.

The New Orleans Times-Picayune wondered in print if Williams would be hired to head up the Pelicans in 1942,17 and indeed he was purchased by the Pels in January. He had a bad knee, however, and simply rode the bench. In early May, he was released outright to the Columbus Red Birds. He played in 84 games and hit .274. Late in the year, he joined the war effort by joining the United States Army.

Williams trained at Fort Benning, Georgia, became a sergeant serving in a tank battalion during the war, moving on to Fort Knox and Fort Ord.

After the war, he managed the Augusta (Georgia) Tigers in the South Atlantic League to back-to-back fourth-place finishes. In late December, he signed to manage Lancaster for 1948. The team finished in last place; he was replaced before the year was over. It was his last year in baseball.

Williams worked as a farmer in Greenbrier, specializing as an egg producer with the Greenbrier Egg Co.

Dib Williams died in a nursing home in Searcy, Arkansas at the age of 82, on April 2, 1992.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Williams’ player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Climbs Over the Mountain,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1933: 1.

2 James C. Isaminger, “Williams Native of Real Baseball Town,” unidentified newspaper, March 23, 1930. Clipping found in Williams’ player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Ibid. Attempts to find the Cato brothers in the US census, and to determine whether one might be actually “Louis” rather than “Lois” proved fruitless.

4 Bill Dooly, “Dib Williams, the Pride of Greenbrier, Ark., Unsung Hero of Last Year’s World Series,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1931: 3.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 See, for instance, coverage in the San Francisco Chronicle, October 10, 1931: 28.

8 “Cardinals Jolt Athletics, 4-2, In Series Final,” Trenton Evening Times, October 11, 1931: 25.

9 Eddie Collins, “Athletics Sorry for Connie Mack,” Boston Globe, October 11, 1931: A10.

10 John McGraw, “John McGraw Explains Big Plays of Last World Series,” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1932: A13.

11 “Collins Closes Question of Deal with A’s for Dib Williams,” Boston Herald, January 21, 1935: 7.

12 “Red Sox Get ‘Dib’ Williams From A’s Utility Man,” Boston Globe, May 2, 1935: 21.

13 Arthur Sampson, “Red Sox Send Williams to Syracuse, On Option, While Retaining Kroner; Graham, Mustaikis Go To Little Rock,” Boston Herald, April 1, 1936: 33.

14 “Dib Williams Takes Farming With A Smile,” Boston Herald, April 3, 1936: 50.

15 “Dib Williams Is Named Pilot of Decatur Team,” Sacramento Bee, January 13, 1941: 10.

16 Ibid.

17 Wm. McG. Keefe, “Viewing the News,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 28, 1941: 60.

Full Name

Edwin Dibrell Williams

Born

January 19, 1910 at Greenbrier, AR (USA)

Died

April 2, 1992 at Searcy, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.