Dud Lee

Shortstop Dud Lee played one game for the St. Louis Browns in 1920, under one name, and two games for the 1926 Boston Red Sox under another. In between, he appeared in another 251 big-league games, compiling a .223 batting average and 60 RBIs. He never hit a home run, under either name.

Shortstop Dud Lee played one game for the St. Louis Browns in 1920, under one name, and two games for the 1926 Boston Red Sox under another. In between, he appeared in another 251 big-league games, compiling a .223 batting average and 60 RBIs. He never hit a home run, under either name.

The shortstop (and sometime second baseman) was born, perhaps, as Ernest Holford Lee in Denver, Colorado, on August 22, 1899.

Lee’s parents were William Lee, a grocery store clerk in Denver at the time of the 1910 census, and William’s wife Anna. He was their only child. He was given his mother’s maiden name as his middle name. Anna was a native Coloradan; William had come from Ohio. Ernest attended Byers Elementary School and then West Denver High School, completing his formal education after the 10th grade.

The question of his name is one for which we have no answer. In the 1910 and 1920 censuses, and in 1918 when he registered for the military draft, he was listed either as Ernest H. Lee or as Ernest Holford Lee. But somehow he is listed in most baseball records and newspaper accounts as Ernest Dudley Lee, and that is how he listed himself when completing a questionnaire for the National Baseball Hall of Fame around 1960. Most of the newspapers in 1920 and 1921 ran his name in full as Ernest Dudley Lee, though he was also described as “Ernest Dudley” even in his own hometown Denver Post. When he signed the completed form, he put “Dudley” in quotation marks as part of his signature. He did indicate that his nickname was “Dud.”1 The mystery of why and how the “Dudley” got into Ernest Holford Lee was finally revealed in The Oregonian in 1936. When he was a small boy, there had been a song with lyrics that included the phrase, “Oh, Mr. Dudley” – which young Lee sang incessantly.2

His father died sometime in between, and Anna’s mother Maggie Holford came to live with the family. Anna worked as a private family dressmaker at the time of the 1920 census.

The first year he went pro was 1920. He’d been playing ball locally for three years, and very close to his 20th birthday, he was signed to a St. Louis Browns contract in August 1919. The Denver Post said the signing came on the recommendation of Frank Newhouse after he played in a Post baseball tournament.3 A later story that offered more depth said, “he could catch a ball standing on his head in grammar school,” that he played high school ball and then semipro around Denver and that it was while playing in an oil league in Wyoming that he was discovered by a St. Louis scout.4

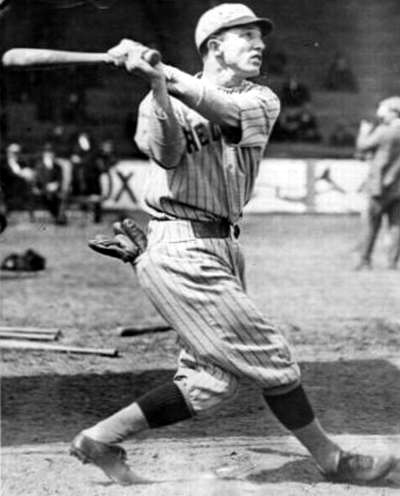

He was described as a “clever little shortstop” in the August 1919 news story, which gave his name as Ernest Lee Dudley. The man in question is listed at 5-foot-9 and 150 pounds. He threw right-handed, but batted left-handed.

Lee went to spring training with the Browns at Taylor, Texas. Needing to get some professional experience, he was not surprisingly asked to play for the Chattanooga Lookouts in the Southern Association that season; he appeared in 138 games for the Class A team, batting .232. Throughout his entire 17-year minor-league career, we find no trace of him playing any position other than shortstop.

Lee was brought up to St. Louis after the Lookouts season ended. The one game in which he appeared was in St. Louis against the visiting Chicago White Sox. And box scores showed his surname as “Dudley.” The Browns won the game, 16-7, but it was far from one which was fiercely contested. Browns manager Jimmy Burke even put first baseman George Sisler on the mound for the final inning; he didn’t allow a hit and struck out two.

Burke “sent in some of his youngsters,” too – our man among them.5 Lee took over for Wally Gerber at shortstop. He committed two errors in three chances – the other play earned him an assist) – for a fielding percentage of .333. He was perfect at the plate, however, singling twice and executing a sacrifice, driving in one run and scoring two.

In 1921, he had a solid opportunity. Lee (we’ll call him that) played in 72 games, though less frequently in the second half of the season – only 11 games after July 5. There was, perhaps, a run-in of some kind with manager Lee Fohl.6 His batting average was anemic, never getting above .200 from May 24 on and finishing up at .167 in 201 plate appearances. He was sometimes used as a pinch runner, particularly early in the season. His on-base percentage was .235. He scored 18 runs and drove in 11. His slugging percentage was .211. His time in the field was split almost equally between second base (through early June) and shortstop (later on); though not playing his usual shortstop, he put up better fielding numbers at second (.961 to .922). His lack of offense understandably hurt his chances for the future. It was back to the minors in 1922.

He was initially with Columbus. the Rocky Mountain News reported that a Columbus newspaper had called him “the flashiest infielder ever seen in the double A,” adding, “were he able to hit more consistently would be a star in any league.”7 He had suffered a hand injury, too. A week later, he was sent to Chattanooga. He still had time to get into 80 games, and hit .263.

By December 1922, the Denver Post finally seems to have gotten it right: Ernest “Dudley” Lee. The December 3 paper reported that his contract had been sold to Tulsa.

Tulsa was Single A, and Lee excelled in the 1923 Western League, hitting .340 for the Oilers with 12 home runs (more than double the amount he had in any other year; he hit five in 1928 for the Hollywood Stars.) Tulsa finished in second place, missing first by two games. Lee had a .959 fielding percentage.

On December 12, the Boston Red Sox paid Tulsa a huge sum to sign him up, reportedly $50,000 plus the contract of Johnny Mitchell. It was close to half what the team had sold Babe Ruth for just four years earlier. Reporting the signing, Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald wrote, ‘He is said to be a second Rabbit Maranville.”8 One of the reasons for the comparison was that the 150-pound Lee “is always willing, like Maranville to pick a fight with a giant who happens to weigh 250 pounds or so.” Some papers at the time said he weighed no more than 135 pounds and maybe as little as 125. Bob Quinn of the Red Sox relied to some extent on manager Lee Fohl, who had worked with Lee in St. Louis in 1921. The Yankees (and maybe four other clubs) were said to have been hot after Lee as well. Quinn was business manager for the Browns at the time when they had initially signed Lee off the sandlots in Denver, and he’d had his eye on Lee ever since. Fohl said, “He is sure one very sweet ballplayer and there is no major league team on which he would not fit.”9

It was acknowledged that he’d never hit that well before Tulsa, but he blamed that in part on getting too much advice from too many different people.

In January 1924, the Washington Post allowed that the Red Sox may be relying too much on Lee coming through, since they really had no one to take his place should he come up short. Their article suggested that Quinn may have been too enamored with Lee as a prospect.10 It took the Sox a while to get Lee to agree to a contract. He no doubt knew what they’d paid Tulsa and wanted a larger salary for himself.

Quinn wasn’t alone. He wowed veteran Hugh Duffy who saw him get better and better during spring training and said that “Boston fans are going to go crazy over the boy.”11

The Boston papers indeed raved about his plays early on, but he fell short on offense. A couple of injuries cost him some playing time, but he had a fair trial, getting into 94 games. Looking back on his record at year’s end, he hit .253 (but the team average was .277), and drove in 29 (ranking him ninth on the ballclub.) He scored 36 times, tied for seventh on the team. He may have executed some flashy plays on the field but he still made 30 errors (.937). In other words, he showed competence but not any more than that. He had one true standout game, going 4-for-4 (with two triples) and driving in three runs in the second game of the July 11 doubleheader against the visiting Browns.

Lee was a holdout in 1925 and a late arrival at spring training. That cost him, as did an injured thumb near the end of the exhibition season, because Bud Connolly got a chance to show his talents and earned a starting role when Opening Day rolled around. Lee had gotten married in early March, to Margaret Morton Hall. He played his first game of 1925 on May 26, and ultimately got into 84 games in 1925, but the Red Sox were clearly looking around for alternatives – they had six other shortstops during the course of the year – Bud Connolly (34 games), Jack Rothrock (22), and Herb Welch, Turkey Gross, Joe Lucey, and Chappie Geygan. Lee batted much lower than the year before – .224, with only 19 RBIs. His OBP and power numbers dropped off significantly, too. It was really only in the final days that his average ticked up to as high as he finished. He was well under .200 almost all season long. This was clearly not what the Red Sox had banked on.

He said he wanted to redeem himself in 1926, and on Opening Day, Lee played shortstop. He was 0-for-4. He played the next day, too, and was 1-for-4. He didn’t get a chance to play again. On May 10, after three weeks riding the bench, he was released unconditionally to the Hollywood Stars. There he found a home.

For seven years running, 1926 through 1932, Lee played for Hollywood. He played steadily, over 160 games a year for every year that we can find records, and hit satisfactorily, .228 in 1926, .248 in 1927, and then averaging in the upper .260s for his last five years. His fielding was strong, at one point in 1928 handling 201 chances without an error.12 In 1930, he was named field captain. He set a PCL record that year, handling 12 assists in one game, the October 9 game against Sacramento.

On January 22, 1933, the Stars sold his contract to Indianapolis (American Association). Hollywood had started to play more night baseball, and Lee didn’t like playing at night. He played well in 1933 and 1934, consistent with the standard of play he’d set with the Stars. In the winters, he returned to Southern California and played semipro ball in the Winter League.

He played with New Orleans in 1935, hitting .241, and also played 30 games for Dallas. He was signed by the Portland Beavers in February 1936 and played for them in ’36 and again in 1937, batting .250 and then .235.

On June 20, 1938, Lee was released by Portland. He’d played in 69 games that year, batting .247, but his fielding had fallen off to a .928 percentage. What did he do next? He took up sports journalism, at least briefly, writing a column on baseball for the Studio City News. 13

His final year in baseball was 1939. In March, he was signed as playing manager of the Dayton Wings of the Class C Middle Atlantic League. He played in 70 games and hit .262, but the team was mired in sixth place and management executed an eight-player trade with the Pine Bluff Judges (Cotton States League), Lee and three others going to the Arkansas team and Andy Cohen (who became Dayton’s playing manager) and three players heading to Dayton. Lee hit .260 for Pine Bluff (in Class C), but his fielding percentage dropped to .901 there. His time in pro ball was done.

He tried to hook on with Seattle in 1940, attending their camp at San Fernando in the springtime but did not succeed.

As the United States stepped up production for the war many believed was coming, Douglas Aircraft of Santa Monica added more personnel, including a lot of L.A. area athletes – among them Dudley Lee.14

Lee died on January 7, 1971, in Denver after undergoing brain surgery to remove a clot.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Lee’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 The June 12, 1921 Denver Post said he was named “Dudley Lee…or as he was known here when he was playing with the Schwartz team and in The Post tournament, Ernest Dudley.” A month later, in the July 21 issue, he was “Ernest (Lee) Dudley.”

2 The Oregonian, December20, 1936. (The same story, however, reported that his full name was Ernest Lee Halstead.)

3 Denver Post, August 30, 1919. See also the February 9, 1920 Post.

4 Boston Herald, December 18, 1923.

5 Boston Herald, October 4, 1920.

6 Denver Post, July 21, 1921.

7 Rocky Mountain News, June 29, 1922. The paper called him Ernest Dudley Lee.

8 Boston Herald, December 13, 1923.

9 Boston Globe, December 13, 1923.

10 Washington Post, January 7, 1924.

11 Boston Globe, March 29, 1924.

12 The Los Angeles Times ran a column on July 22, 1928 crediting Lee’s proportionately large hands with his talent at fielding.

13 Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1938.

14 Los Angeles Times, April 29, 1941.

Full Name

Ernest Holford Lee

Born

August 22, 1899 at Denver, CO (USA)

Died

January 7, 1971 at Denver, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.