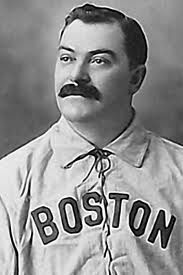

Duke Farrell

Duke Farrell played for two major-league teams in Boston, with 11 seasons in between. He led the American Association in home runs and runs batted for the 1891 Boston Reds, and then played in the first World Series ever staged, in 1903 for the Boston Americans, who became the Boston Red Sox. Both teams finished first in their respective leagues.

Duke Farrell played for two major-league teams in Boston, with 11 seasons in between. He led the American Association in home runs and runs batted for the 1891 Boston Reds, and then played in the first World Series ever staged, in 1903 for the Boston Americans, who became the Boston Red Sox. Both teams finished first in their respective leagues.

The big switch-hitting catcher (he was 6-feet-1 and weighed 208 pounds (in his earlier years, and still quite large for the 19th century) came from Oakdale, a village in Western Massachusetts that was not far from Holyoke. That’s the listed place of birth on August 31, 1866, for Charles Andrew Farrell, known in baseball as Charley Farrell or Duke Farrell. His father, Michael Farrell, worked in a shoe store in Marlborough, Massachusetts at the time of the 1870 census. His mother, Ellen (Gately) Farrell, kept house, with a growing family. Both Ellen and Michael Farrell were immigrants from Ireland, arriving in 1848 and 1850 respectively. Charles was the first-born. He attended elementary school in Oakdale, and then (after the Farrell family moved) at the Bigelow Grammar School in Marlborough, just east of Worcester, for a total of nine years of schooling.1

By the year 1900, Farrell was still living at home in Marlborough with both parents and his younger sisters, Mary, Eva, Gertrude, Rose, and Blanche. In 1900 Michael was working as a day laborer. Charley was working as a ballplayer. By 1900 he had 13 years of professional baseball experience under his belt, and had played for seven different teams.

Farrell had begun playing baseball in Marlborough, pitching when needed, but mostly catching, and working at times at a local shoe factory. His first professional baseball came in 1887 at the age of 20, when he played for the Lawrence, Massachusetts, team in the New England League (which transferred location to Salem during the season). Farrell played in 47 games, 31 of them as a catcher but also 11 in the outfield, nine at second base, three at first base, and one at third base. He had a very good year at the plate, batting .376 (three men on the team hit over .400 – Patsy Donovan, Howard Earl, and Irv Ray, all of whom made the majors.) Farrell hit four home runs.

Tim Murnane, a major-league player who later became a minor-league president and sportswriter, claimed credit for signing Farrell (and Hugh Duffy) to play in 1888 for the National League’s Chicago White Stockings.2 Farrell split his time almost evenly between catching and outfield work for the manager, Cap Anson. Right from the start, he got a little attention. The April 4 issue of Sporting Life said of an exhibition game against New Orleans, “Farrell’s catching and throwing was the feature of Chicago’s play.” And as early as the beginning of June, the same publication reported that the Pittsburgh ballclub was trying to buy his contract, but that owner Al Spalding refused to sell. In mid-June the Chicago team played an exhibition game in Farrell’s hometown of Marlborough. Farrell’s friends presented him with a “handsome gold watch.”3 Farrell hit .232 with three homers and 19 RBIs. He later gave Anson every credit for developing him as a ballplayer.4 In October Farrell married Julia A. Bradley of Marlborough. They had a daughter, Grace. Mrs. Farrell died before the turn of the century, and Grace was taken in by Farrell’s parents and his five sisters.

The next year, 1889, Farrell bumped up his average to .263 and homered 11 times, driving in 75 runs. In 1890, the year the players formed the Baseball Brotherhood and the Players League, Farrell switched leagues but stayed in Chicago, playing for the Chicago Pirates of the Players League for manager Charlie Comiskey. Both he and Hugh Duffy were stockholders in the club. By now he was a highly-regarded player. In its June 14, 1890, issue, Sporting Life wrote, “One thing is very noticeable about the work of Comiskey’s team, and that is that the two men who were the young bloods of Anson’s team last year are doing the best work of the team to-day(,) the best batting, fielding, and base-running. I refer to Duffy and Charley Farrell.” King Kelly’s Boston Reds took first place, in the one and only season the league was in existence.

Farrell’s 84 RBIs were second on the Pirates team. He hit for a .290 average. In both 1889 and 1890 he played the lion’s share of his time as catcher. After they were initially reported to have signed a contract to play in Lowell, Massachusetts, both Farrell and Duffy signed with the 1891 Boston Reds team, now in the American Association (but still considered a major-league team), managed by Arthur Irwin.5 Farrell was already being hailed by the Boston Globe as “the king of all catchers.”6 Tim Murnane, now in his sportswriting mode, described Farrell’s “happy disposition,” said he was one of the fastest players in the game, and said he “loves to be in every game and is always in the pink of condition.”7 Farrell played in 66 games at third base (after Bill Joyce broke his leg), 37 at catcher, and 23 in the outfield. He also played four games at first base. Boston finished first one more. Farrell was a big part of the victory. He led the league in runs batted in (with 110) and home runs (12), while hitting for a .302 average and scoring 108 runs. All except his batting average remained career highs, as did his 21 stolen bases. His 110 RBIs were tied with Reds outfielder Hugh Duffy.

The Reds played their last game in Marlborough. The American Association folded after the 1891 season, and the league was consolidated into the National League – with seven of the 12 NL clubs putting in a claim on Farrell.8 At a “consolidation meeting” held in Indianapolis, the Pirates acquired the rights to Farrell’s contract for 1892.

Farrell played mostly at third base for the Pirates, and also in the outfield, but without catching even one game. He played in 152 games, the most of his career, but had an offyear at the plate, just hitting .215. He drove in 77 runs, second-most on the sixth-place Pirates.

There was one way in which Farrell declined to fit in. Whether it had anything to do with his having an offyear is unlikely. “The mustache brigade has succeeded in getting every player in the Pittsburg team to cut off his beautifier, except Charley Farrell, who vows that it may be a Jonah, but he is going to keep it there.”9

Just as he’d increased his batting average for each of his first four seasons, beginning with 1891 Farrell started to climb that ladder again, and for each of four more years in a row, he improved over the prior year, if only marginally at times – from .215 to .282, then .287, .288, and .290.

He preferred not to play in Pittsburgh “because of certain people there who were unfriendly to him” and a correspondent from Boston wrote, “Charley Farrell turns up so often that one might suppose that he lived here. Charley wants to get away from Pittsburg without a doubt. It is poor policy to make a player go where he does not feel at home.”10 He thought he’d been promised a release, but Pittsburgh wasn’t willing to let him go without getting anything in return. He was traded to the Washington Senators on March 21, 1893, for pitcher Frank Killen (with a reported $1,500 going to the Senators, too.) The trade was dubbed a “bombshell” but also seen as good for both teams. Regarding Farrell, Sporting Life’s reporter wrote, “The great advantage of having Farrell in the team is his splendid ability to play ball and his knowledge of the fine points of the game. He is admittedly one of the best catchers in the business, and is besides a good infielder or outfielder. His greatest value to Washington will be the strength he will add to the backstop department. With O’Rourke and Farrell to alternate behind the bat and in left field it will keep both these heavy stickers constantly in the game.”11

There was a hitch when Farrell “positively refused to catch” – but a week later, it was clear he was being counted on to catch. As it transpired, he caught in 81 games, played third base in 41 games, and played first base in three.12

O’Rourke was player/manager Jim O’Rourke, and Farrell hit the aforementioned .282, and put to rest the criticism regarding his play during 1892. The team finished 12th in the 12-team league. Nonetheless, he was pleased with his stay in Washington, and rumors in the autumn and over the winter that he’d be sent to St. Louis didn’t set well with him. He kept busy in the offseason building a new house in Marlborough, moving in on the first day of 1894.

A little under a year after he’d been dealt to Washington – on February 27, 1894, Farrell was on the move once again, traded (with pitcher Jouett Meekin) to the New York Giants for a package comprising first baseman Jack McMahon, pitcher Charlie Petty, and $7,500. (After 2½ years, he was traded back to Washington.) Farrell was pleased with the trade to the Giants, anticipating that they were going to have a better future. There followed some controversy because of the large price paid, and the fact that the Giants asked Farrell to take a pay cut, but it was apparently worked out to his sufficient satisfaction.

In 1894, his first year with the Giants, managed by Monte Ward, Farrell drove in 70 runs. The Giants finished in second place, just three games behind Brooklyn. Farrell led the league in most putouts and most assists by a catcher, but also in most passed balls and most errors. With 158 runners caught stealing, he also led the league in that statistic as well.

The 1895 team went through three different managers and finished in ninth place. Farrell appeared in only 90 games, and – reflecting a reduced role – drove in just 58 runs. By this time, even though he’d said it wasn’t his preferred position, Farrell was catching more than anything else; he caught in 105 games in 1894. He did say he was glad to play anywhere Ward wanted him to play. In 1895 he caught about two-thirds of the time, usually playing third base otherwise.

Unlike some players whose nicknames in the record books are rarely found in contemporary news accounts, by 1895 Farrell was frequently being called “Duke” or “The Duke.” The Boston Globe had referred to him as “the duke of Marlborough” back in 1893.13 The title was, however, bestowed on him by one of the earliest concessionaires associated with the game, Harry M. Stevens – the “score card man” – during an 1891 exhibition game at Rocky Point in Warwick, Rhode Island, when Farrell was with the Boston Reds in 1891.14 An earlier account, published in 1901, also ascribed the nickname to Stevens in 1891 but said that Farrell earned it by eating more than 380 clams.15

Two old mates managed the 1896 Giants – Arthur Irwin and fellow teammate Bill Joyce. But as Joyce came in, Farrell went out. He’d begun the season well, batting .283 in 58 games (and even played 13 games at shortstop – though committing 15 errors in those games), but an August 1 trade did send him back to Washington. New Yorkers applauded the move to acquire Joyce: “Cranks, rooters, fans and others were treated to a great surprise last Friday, and Saturday their delight became ecstasy. The addition of [Jake] Beckley and [Jack] Warner to the New York Club was a great move on the part of the management, and when the announcement was made that Scrappy Bill Joyce had been secured in exchange for Charley Farrell, pitcher [Carney] Flynn and $2,500 in cash the drooping spirits of the Gothamite base ball followers revived as if by magic.”16 The Giants still finished in seventh place.

Farrell picked up his game, batting .300 and driving in 30 runs in 37 games for the Washington Nationals. And he hit very well in 1897 (.322, with 53 RBIs in 78 games). He also set a major-league record on May 11 against Baltimore, throwing out eight of nine would-be base stealers. The eight caught stealing in a game is a record set in the 19th century that still endured in the second decade of the 21st century.

After the 1897 season, Farrell was only 31 years old. He had even done some scouting, recommending pitcher Stephen Ashe to the Senators. “It means something to him to have Charley Farrell as sponsor,” Sporting Life said. “Farrell during the past six years, has worked in harness with the greatest pitchers of the country. He knows the qualifications required of a young pitcher in fast company, and he avers that Ashe has a bright future.”17

The year 1898 started out tragically, when Farrell’s wife died on February 15, but he did have another strong season – .314, with 53 RBIs again, in 99 games. On April 25, 1899, Washington and Brooklyn executed a trade, with the Superbas sending the Senators three players and $2,500 for Farrell and thitd baseman Doc Casey. E.P. Mills wrote from Washington, “I do not think that anyone will kick very hard over the departure of Casey and Farrell, as the recent disastrous showing of the Senators made it apparent that some effort must be made to strengthen the team.”18 At the same time, Brooklyn fans were pleased to see their team “doing its utmost to provide base ball of the very best nature. It has been a long time since Brooklyn has seen selections made of players with skill.”19 Farrell drove in a run his first time up. He hit .299 for the season, with 55 RBIs. He was exceptionally well-regarded, with sportswriter W.A. Phelon, Jr. writing, “As catchers go nowadays, I don’t know but what I’d rather have Charley Farrell than anyone I know.”20 Farrell left an 11th-place team and had joined a first-place team. Brooklyn finished 101-47, eight games ahead of the second-place Boston Beaneaters.

And Brooklyn finished first again in 1900. The next time they would win the pennant was 1916.

“Farrell’s Plaint” – such was the headline in the November 10, 1900, Sporting Life. Farrell “was a much maligned man” during the season, and he told the Brooklyn Eagle, “I was handicapped right at the start by the statement that I weighed a ton and couldn’t play. Now, personally I didn’t care for the newspaper comments, but the bleacherites got onto it and they had lots of fun with me right through the season. In fact, they never let up.” In fact, he said, he weighed 15 pounds less and had one of his best seasons. The publication said that “the services of both the Duke and Jim McGuire, in winning the championship, have been over looked in the adulation showered upon some of the other players of the team. They have alternated behind the bat day in and day out during the entire season, giving their best services at all time without ostentation and never stooping to grandstand playing, such as characterizes the work of some of the younger generation of backstops. They have steadied the team at all times and have been of great assistance to the pitchers.”

Teammate Wee Willie Keeler (listed a 5-feet-4 and 140 pounds) told a story that touched on Farrell’s size: “Talk about seeing funny things on the ball field, there was one incident last summer that I never think of without a good laugh,” Keeler said. “It happened just before a game. Duke Farrell and I were strolling along in front of the grandstand, chatting together about something, when the scorecard boy at the entrance got this off: ‘Get your score cards, ladies and gents. You can’t tell ’em apart. They all look alike!’ I looked over Farrell’s six feet of height and 220 pounds of weight and then thought of my own size and height … and then I ran.”21

They still remembered Farrell fondly in Boston, and Hub sportswriter Jacob Morse recalled, “There never was a more popular player in Boston than Charley Farrell, and the lovers of the game were sad indeed when he left us in 1891.”22 Duke eventually returned to the Boston roster, but he played two more seasons in Brooklyn before he did.

With Ban Johnson’s new American League actively recruiting players with a pitch that might well have appealed to those who had been members of the Baseball Brotherhood, and with former pal Hugh Duffy among the more active recruiters (not to mention managing the Milwaukee team in the AL), Farrell did in fact stick with Brooklyn for 1901 and 1902. Though he lost some playing time due to a spiking and consequent blood poisoning in June 1901, he played in 80 games – the only position he played was catcher – and hit .275.

Farrell hit .246 in 74 games in 1902 and drove in only 24 runs, his lowest total since he broke in back in 1888. Brooklyn finished in second place. After the season Duke said he was looking forward to another season playing for Ned Hanlon, manager of the Brooklyns since 1899.23 Hanlon, however, may have felt Farrell had not kept himself in good physical shape.

It was as late as mid-March 1903 when word came that the Boston Americans were after Charley Farrell. Jimmy Collins and the Boston team were training in Macon, Georgia. Catcher Jack Warner of the 1902 Bostons had jumped his contract to play for the New York Giants. Some reports have Farrell jumping his contract to join Boston, but he told a different story himself, After rhapsodizing about Hanlon as a manager, he said he’d been weakened by malaria for about a month in 1902, causing a precipitous fall-off in his play and a ten-game hitless slump. “This may have had something to do with my release,” he said, “but I went to see Hanlon, and he gave me permission to do business elsewhere, and I wired Collins, and he agreed to my terms.”24

Despite his praise of Hanlon, Farrell hadn’t been as pleased with Brooklyn ownership. He claimed unjust treatment and that he would not sign with Brooklyn because the team had withheld two weeks’ salary when he was ill near the end of the 1902 campaign.25

Hanlon himself was generous in his praise of Duke: “He’s a catcher with more brilliancy in his bonnet than half the backstops in the two leagues, and for coolness and ability in action, can’t be beat. He works with skill and judgment, whether things are going right or wrong, and nothing ever phases him. That’s the kind of catchers that make pennant winners.”26

Farrell ultimately informed Hanlon that he wasn’t coming back, and that Boston was looking for a backup catcher for Lou Criger, John Warner having left the team to jump back to the New York Giants. He thought he could fit in well with Boston, and on March 18, Farrell accepted terms.27 He reportedly managed to lose nearly 20 pounds in spring training and even shaved off his handlebar mustache, helping him look a little younger.28 And he won the honor of starting the season.

A record-breaking crowd packed Boston’s Huntington Avenue Grounds for Opening Day on April 20 and Farrell caught both the morning and afternoon games, going 3-for-6 at the plate without an error while Philadelphia and Boston split. His first time at bat, the game was interrupted so the Royal Rooters could present him with a diamond ring, welcoming him back to Boston, the site of the 1891 pennant he’d helped win. Several days later Tim Murnane wrote in the Boston Globe that Farrell “even to this day has no superior behind the bat, and he is strong in every department.”29

The very day after Murnane’s praise, Farrell broke his leg on April 27 during a 6-3 loss in Washington. Still popular in Washington, when he came up to bat in the top of the second inning, he “was given the greatest ovation a visiting player ever received on a Washington ball field.” He singled to right field, and then attempted to steal second, but his spikes caught in the ground in front of the base and he broke a bone in his leg just above his right ankle. He was 9-for-16, with 12 total bases at the time.

Farrell rejoined the team on September 17, the day after the team had clinched the AL pennant. He finished the season appearing in just 17 games, with a .404 average and eight RBIs. In the World Series against Pittsburgh – the first World Series – Farrell appeared in two games, pinch-hitting for Cy Young in Game One and grounding out to end the game, and then pinch-hitting again in Game Four, driving in a run with a ninth-inning sacrifice fly (in a 5-4 loss.)

Over the course of his career, Farrell was apparently a very successful pinch-hitter. An article in the Marlboro Enterprise quoted noted baseball publicist Ford Sawyer as having calculated that over a nine-year stretch, Farrell had 54 plate appearances as a pinch-hitter and hit safely 22 times.30

A few weeks after the Americans won the World Series, Tim Murnane enthused about Farrell yet again, not for his work in 1903 but generally: “Taking into account his batting, his head work and his disposition to stand the whip, Farrell is the greatest catcher the game has produced.”31

The Duke said 1904 would be his last year. He trained with the team in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1904 and played in 68 games, batting .212 with15 RBIs, while Boston won the pennant again. The National League champion New York Giants refused to play a World Series. With his 1891 American Association pennant and now back-to-back ones with the Boston Americans, Farrell was a perfect 3-for-3 in pennants while playing for Boston ball teams.

Farrell caught Jesse Tannehill’s no-hitter on August 17, 1904, against the White Sox in Chicago, and helped by making a very good catch on a twisting foul fly. But in mid-September, as the season approached its close, Farrell continued to contemplate retirement.32 He’d played 17 seasons in the major leagues and turned 38, and he’d broken the middle finger on his right hand on September 6.

Farrell had reportedly been offered a job managing a Pacific Coast League team, but wasn’t ready to stop playing yet. By Christmas he had lost 35 pounds and was trying to get under 200. Instead of heading to the West Coast, he went south with the Boston Americans again, primarily to work with the pitching staff. In February, Tim Murnane wrote a lengthy biographical sketch of Farrell for the Boston Globe. He said that Farrell “never said an unkind word of another player and never protested a decision by the umpire.”33

Farrell opened the season with the 1905 team but played in his last game on June 13. It was his 1,565th major-league game. His average for 1905 was .286, in 22 plate appearances during seven games. He continued to work with the club, and even did a little scouting work – he was reported as offering $1,000 for catcher Charlie Armbruster of New London in the Connecticut State League after Boston catcher Art McGovern became ill.34 Farrell officially retired on July 27.35 He’d never quite recovered from the broken leg, and experienced increasing difficulty keeping his weight down. He continued to work for team owner John I. Taylor, scouting in the minor leagues.36

In 1909 George Stallings of the New York Highlanders (Yankees) hired Farrell to work with his pitchers during spring training. He worked as a coach and scout for New York in 1909, 1911, and from 1915 through 1917. During the First World War, Farrell served as a deputy United States marshal in Boston. He took the oath of office on April 10, 1918.37

In 1912 Farrell had worked as battery coach for the Boston Nationals. The Braves hired him again as scout and assistant coach in 1923.38 He performed the same duties in 1924, but died on February 15, 1925, at Carney Hospital in Boston, after six weeks of wasting away from an abdominal disorder that prevented him from retaining nourishment. The cause of death was listed as cancer of the stomach. He was survived by his daughter, Grace Armour, and two sisters.

James C. O’Leary of the Boston Globe was effusive in his praise of Farrell in the paper’s obituary: “It is doubtful if a more lovable character ever has been, or ever will be, connected with baseball. … Clean spoken, clean living, Charley Farrell was a character worthy of emulation by all connected with baseball today.”39

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Farrell’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, The Baseball Necrology, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Lyle Spatz for confirming Farrell’s 1897 record.

Notes

1 Charles Farrell player questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, completed by grandson John R. Armour.

2 Boston Globe, April 26, 1903, and February 26, 1905.

3 Sporting Life, June 20, 1888.

4 See the Washington Post of April 24, 1904 for a full portrait of Farrell.

5 Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1891.

6 Boston Globe, March 7, 1891.

7 Ibid.

8 Chicago Tribune, January 3, 1892.

9 Sporting Life, June 4, 1892.

10 Sporting Life, December 24, 1892. The problem seems to have been with Pirates manager Al Buckenberger. See the Boston Globe, September 17, 1903.

11 Sporting Life, March 25, 1893. The March 28 Washington Post commented on the “unfriendly” folks in Pittsburgh.

12 His refusal to catch was reported in the Washington Post of March 21, 1893.

13 Boston Globe, December 31, 1893.

14 Boston Globe, February 16, 1925.

15 Sporting Life, January 5, 1901.

16 Sporting Life, August 8, 1896.

17 Sporting Life, January 30, 1897.

18 Sporting Life, April 29, 1899.

19 Sporting Life, May 6, 1899.

20 Sporting Life, June 17, 1899.

21 Sporting Life, November 17, 1900.

22 Sporting Life, January 13, 1900.

23 Washington Post, November 9, 1902.

24 Washington Post, April 24, 1904. The malaria had also been reported in the August 16, 1902 Sporting Life, which praised Farrell for working when the team needed him badly and despite his condition, adding, “Goodness knows how far Brooklyn might not have been down had it not been for Farrell.”

25 Sporting Life, January 10, 1903.

26 Sporting Life, May 9, 1903.

27 Boston Globe, March 18 and 19, 1903.

28 Rich Eldred, “Charles Andrew Farrell” in SABR’s book Nineteenth Century Stars, 1989 (reprinted 2012).

29 Boston Globe, April 26, 1903.

30 Marlboro Enterprise, February 25, 1930.

31 Boston Globe, November 8, 1903.

32 Washington Post, September 11, 1904.

33 Boston Globe, February 26, 1905.

34 Hartford Courant, July 12, 1905.

35 Boston Globe, July 28, 1905. The story of Farrell’s retirement reported on the offer to manage in the Pacific Coast League.

36 Sporting Life, September 2, 1905.

37 Boston Traveler, April 11, 1918.

38 Boston Globe, February 28, 1923.

39 Boston Globe, February 16, 1925.

Full Name

Charles Andrew Farrell

Born

August 31, 1866 at Oakdale, MA (USA)

Died

February 15, 1925 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.