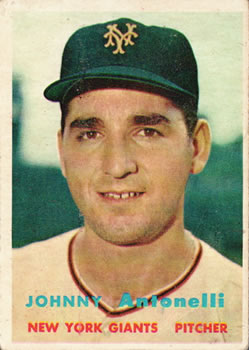

Johnny Antonelli

Johnny Antonelli, somewhat unfairly, is remembered by the incidents he was part of, instead of as an individual who had an impressive pitching career. Labels abound and, of the memories attached to them, controversies.

Johnny Antonelli, somewhat unfairly, is remembered by the incidents he was part of, instead of as an individual who had an impressive pitching career. Labels abound and, of the memories attached to them, controversies.

He was, in the minds of many, a “bonus baby” who never paid his dues in the minors. A player on a National League championship club who was not voted a World Series share by his Braves teammates. A rarely used pitcher for Boston who had the gall to make more money than Warren Spahn. A relative unknown who was traded for October heroes and former batting champs. A malcontent, who at a certain point was one of the most despised players in San Francisco Giants history. A southpaw who, rather than play for an expansion team, chose to retire from baseball for good.

It would be wrong, however, to remember Antonelli in this fashion. He was a good southpaw whose pitching was masterful when he was healthy and brilliant when he was at ease. He wasn’t perfect, but the decisions he and his family made — especially the decision to take a boatload of Lou Perini’s money — are no different than those most any teenager with big league dreams and strong self-confidence would have undertaken.

John August “Johnny” Antonelli was born on April 12, 1930, in Rochester, New York, to Augustino “Gus” Antonelli and Josephina Messore. From Johnny’s first year at Rochester’s Jefferson High School, where he was a three-sport star (basketball, football, and baseball), he attracted major-league publicity and major-league scouts. Johnny’s father, Gus, a railroad construction contractor who had immigrated to the United States from Abruzzi, Italy, in 1913, was actively involved in nurturing and promoting his son’s baseball career. Johnny remembers that his father would “go down to spring training every year, and bring along my scrapbook and brag about me.”1 The scrapbook Johnny refers to was a bulging tome, filled with newspaper clippings and pictures of the young Antonelli from his high school years. Occasionally, great ballplayers like Joe Cronin, Bobby Feller, and Leo Durocher were invited by the elder Antonelli to come to Rochester to take a look at both the scrapbook2 and the loping curve that Johnny had developed in the semipro Vermont Hotel League in 1947.3

During those high school years, Johnny played baseball under coach Charley O’Brien, who converted him from a freshman first baseman to a pitcher (despite the teenager’s protests). Watching his son develop rapidly as a sophomore and junior hurler and fearing he might hurt his arm, Johnny’s father made him quit football and focus on baseball full time.4 The teenager threw three no-hitters and drew praise from scouts like Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell, who said that Antonelli had the best all-around stuff he had ever seen.

Gus began to see that his son might be a major leaguer in the making and eventually began taking him to spring training, where Johnny “talked and observed, but mostly…listened and absorbed all he could about talent and procedure.”5 After Johnny graduated from high school in 1948, Gus wrote to a number of ballclubs and then rented out Silver Stadium, home of the International League Rochester Red Wings, to showcase Johnny to the scouts. Nine scouts and 7,000 fans came, and the youngster did not disappoint, as Antonelli struck out 17 batters against a “strong semipro club” on his way to a no-hitter.6

Scouts were enthralled. The Braves, Red Sox, Yankees, Giants, Indians, Tigers, Cardinals, Pirates, and Reds were all interested. Braves scout Jeff Jones called Lou Perini, the club president, to come as quickly as possible. “He’s by far the best big-league prospect I’ve ever seen,” exclaimed the excited Jones. “He has the poise of a major league pitcher right now and has a curve and fastball to back it up. I think so much of this kid’s chances that if I had to pay out the money myself, I wouldn’t hesitate to do it — if I had the money.”7 Jones didn’t have that kind of money, but Perini did, and he got the youngster under contract on June 29, 1948, by giving him an amount reported in excess of $50,000, the largest bonus in baseball history at the time. Johnny has never stated the figure, but indicates that the figures reported in the press were often inflated.

Everyone knew that Gus Antonelli was involved and interested in his son’s future. With the ever-expanding scrapbook, the handwritten letters to scouts, and the staged exhibition games, one could argue that Gus was a bit of an overbearing father, one of those hard-driving Little League dads whom we might click our tongue at today. But the younger Antonelli had aspired to be a major-league player since he was 12 years old and eagerly and dutifully took his father’s counsel. It paid off with the huge bonus, which under the rules required the Braves to put Antonelli on their major league roster, immediately fulfilling the youngster’s dream.

Was there resentment from other Braves players? Almost certainly. Johnny Sain, the team’s gentlemanly, mild-mannered ace, made $21,000 — considerably less than Antonelli’s bonus — and was so upset about the discrepancy between him (a 20-game winner) and Antonelli (with nary a big league appearance) that he threatened to walk out on his contract. “I meant it,” Sain said later on, “I was going to walk away from the whole thing.”8 The club soothed the anger of its star pitcher by giving him a new contract worth $30,000 just before the All-Star break. Antonelli insists today that there wasn’t as much tension with his teammates as the press would have had one believe — that it was actually a good thing for the other players, who used his high paycheck as leverage in salary disputes with Perini.

But the Braves were in the middle of a pennant race and, according to major league rules, the size of Antonelli’s bonus required them to keep him on the major-league roster for at least two years. Consequently, Antonelli sat on the bench for months, an untried teenager with no experience under pressure, simply taking up valuable space on a club that was clawing its way in pursuit of its first National League pennant in 34 years.

The circumstances of his presence on the club sent shock waves throughout the league, and players, writers, and managers weighed in with opinions and speculation. Walker Cooper of the Giants said Antonelli should “…take the 75 gees and call it a career right now.” Jeff Heath, one of Antonelli’s teammates, reminisced about the days when his roommate, Bob Feller, was given a few thousand dollars so Feller’s father could put an addition on the barn — and it was a big deal!9 Mel Ott, the Giants’ Hall of Famer, recalled that for his signing bonus, he received $400 from John McGraw, but was kind enough to say that a “dollar went further” back then. But kind and supportive remarks were few and far between. Whatever the sentiments, Antonelli would battle against the “bonus baby” tag for years to come.

Johnny pitched only four innings during Boston’s historic 1948 sprint to the championship. He finished the season with a 2.25 ERA and a 0-0 record, although he got plenty of pregame activity. While manager Billy Southworth wasn’t willing to risk Antonelli giving away any ballgames, he wasn’t opposed to getting a little out of his bonus baby. So five days a week, Southworth put him to work throwing batting practice for half an hour each day.

Looking back, Antonelli says he bore a lot of disrespect from his bosses and colleagues. Johnny should have been eligible for the World Series, but his spot was instead given to first baseman Ray Sanders, technically ineligible but allowed to play by the league and team anyway out of respect for an injury he had recovered from. When the players divided World Series shares, Antonelli didn’t get a dime (while the batboys each made $380.89). That slight did steam up Antonelli, who said that though he understood Southworth’s decision not to use him during the stretch run, the fact that he had pitched batting practice each day without complaint should have warranted at least a little of the World Series money. The situation was eventually remedied by the league and Commissioner Happy Chandler, who stepped in and conferred upon him one-eighth of a share, about $571.34.

In the winter of 1948, though ineligible for collegiate baseball, Johnny enrolled at Bowling Green University, following his brother Anthony, a junior quarterback for the school. He majored in voice and was active in the choir, causing Oscar Ruhl of The Sporting News to remark that Antonelli would be the second “songbird” on the Braves, joining teammate Red Barrett.

The next season, 1949, was a bit better for Antonelli, but more difficult for the Braves. While Johnny pitched 96 innings with a 3-7 record and a 3.56 ERA, the Braves slipped to fourth place. In one of those wins, a 4-2 win over the Giants on May 1, Antonelli pitched excellently, showing his true potential and startling both teammates and opponents. Even umpire Artie Gore said there was something different about the way Antonelli presented himself on the mound; he marveled at Antonelli’s remarkable confidence in his pitching prowess, and the fact that he was self-assured enough to throw curves “when some pitchers wouldn’t dare.”10

But it was to be the one of the last flashes of brilliance Antonelli had the chance to exhibit with the Braves. In 1950 aces Vern Bickford, Johnny Sain, and Warren Spahn kept the team competitive until late August, and when the season was over those three had accounted for 60 of the team’s 83 wins. Antonelli himself only pitched 58 innings, going 2-3 while his ERA rose to 5.93. The youngster started only six games, and shared the role of fourth starting pitcher with several other players.

In March of 1951, with little fanfare in the Boston sports pages, Antonelli began an active-duty stint of two years with the Army. He spent his time at Fort Myer, Virginia, where he was once again able to flourish. Antonelli had never spent time in the minor leagues (he is one of only 17 people to have completed his major league career without spending a single day in the minors), but at Fort Myer, pitching for his Army team during 1951 and 1952, Johnny went 42-2. The Fort Myer stint resurrected his career and showed the league what he could do with regular starts. In essence, the Army team was like minor league service for Antonelli, who also found relief in the Army from allergies that had previously not been diagnosed or treated.11

By the time Antonelli was discharged in 1953, the Braves had moved from Boston. He found himself a Milwaukee Brave, and when the All-Star Game rolled around, he already had a 8-4 record. Despite his large signing bonus, his salary was only $5,500. After Antonelli became a starter in 1953, general manager John Quinn had given him a raise to $9,000. The young hurler contracted pneumonia, however, and as his strength waned a bit, his record flipped over — turning from a 8-4 first half to a 4-8 second half. Despite Antonelli’s relatively strong showing (his 3.18 ERA was good for fifth best in the league), Warren Spahn suggested that three left-handers (himself, Antonelli, and Chet Nichols, a solid young pitcher returning from the Army) would be too many, and that he preferred Nichols over Antonelli. The club listened to its ace. On February 1, 1954, Antonelli was shipped to the New York Giants in a six-player deal along with pitcher Don Liddle, catcher Ebba St. Claire, infielder Billy Klaus, and $50,000 for outfielder Bobby Thomson and catcher Sammy Calderone. It would be, as Antonelli later called it, “the best break of my career.”12

Bobby Thomson was a hero. On October 3, 1951, he had delivered Giants fans the pennant with his famous “Shot Heard Round the World,” a ninth-inning walk-off home run off Ralph Branca of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the deciding game of a three-game playoff series. Though the Giants lost the World Series to the Yankees in six games, Thomson was forever embedded in Giants lore, and losing him to the Braves shocked and dismayed fans. Antonelli, naturally, was less than a fan favorite as the year got underway, but despite that obstacle he had his best year in 1954.

After leading off the season with a decent 5-2 record, Johnny reeled off eight victories in a row before the All-Star Game, to which he was elected for the first time.13 On May 16, Antonelli faced off with the Braves for the first time since his departure from the Milwaukee club. The Giants were quick and plentiful with their run support against their young southpaw’s former teammates, beating them soundly, 9-2. On June 9, Johnny had another shot at revenge, facing off against Warren Spahn in Milwaukee. Antonelli drove in one of the runs off Spahn and spun a complete game shutout in a 4-0 victory. The next day’s New York Times wrote that “30,018 disconsolate fans looked on in silence.”

By October, Antonelli was the number one starter on the team. All season long, he had been relatively consistent in his dominant pitching. He was vitally important to the Giants, and when the team began to falter in late August, losing seven of nine games, Antonelli stood tall with New York’s only two victories during that dismal streak. Behind his clutch hurling and offensive support from the likes of Willie Mays, Monte Irvin, and Alvin Dark, the Giants advanced to the World Series against the Cleveland Indians.

In Game One, which Antonelli witnessed from the bench, one of the most memorable plays in World Series history took place. With the score tied at 2-2 and two men on base, Cleveland first baseman Vic Wertz hit a fly ball to the deepest part of the cavernous Polo Grounds centerfield. Antonelli, watching from the dugout, recalls centerfielder Mays pounding his glove, sprinting with his back towards home plate, reaching up, and snaring the ball as it streaked over his shoulder. It would come to be known simply as: “The Catch.”

In Game Two, Antonelli started against future Hall of Famer Early Wynn. Johnny had a rocky beginning, giving up a home run to Al Smith on the first pitch of the game, but didn’t allow a run the rest of the game. “The Good Lord was on my side that game,” Antonelli said years later. “I don’t think I had my best stuff that day.”14 But it was good enough to hold the Indians the rest of the way, and give him a win in his first World Series appearance.

After losing Game Three, the Indians, who had gone 111-43 during the regular season, were once again humbled by Antonelli in the fourth contest. Before the game, Leo Durocher, the manager of the Giants, was told by his captain, Alvin Dark, that it was hard for hitters to pick up the ball against lefties because of sun glare off the scoreboard.15 So when Durocher noticed that reliever Hoyt Wilhelm was faltering in the eighth inning, with the Giants one win away from a World Series championship, the manager turned to his best lefty to close it out — and, dutifully, Antonelli did so, getting the last five outs of the World Series on three strikeouts and two popups. When Indians pinch hitter Dale Mitchell popped out in foul territory, Johnny could celebrate both a World Series victory and the completion of a year that transformed him from a question-mark prospect to a successful pitcher, All-Star, and valuable member of a championship team.16 He had led the league in shutouts (6), ERA (2.30), and win-loss percentage (.750). His regular season record was 21-7. Meanwhile, back in Milwaukee, Chet Nichols went 9-11.

After the World Series, Antonelli returned to Rochester, where he was given a hero’s welcome by his hometown fans — made even sweeter since he had received The Sporting News’ Pitcher of the Year award (this being two years before the establishment of the Cy Young). He was honored with a parade and spoke at an assembly at his alma mater, Jefferson High School.17 He was even given a Buick by the local Italian-American Businessmen’s Association.

In Boston he had met and married a young lady named Rosemarie Carbone.. They had made their home in Lexington, Massachusetts, during the years that Antonelli played for Boston, but after the 1954 season he went into business as a Firestone/Michelin tire distributor in Rochester and the family relocated there. He sold the business 40 years later, in 1994.

When Antonelli received a contract offer from the Giants before the ’55 season it was for the same amount as his prior deal, despite his being arguably the best pitcher in the league. Al Dark advised him to send it back to the ownership and general manager Chub Feeney, asking for double or more. He did so, receiving $28,000.

But Johnny had a tough year in 1955, and the Giants sagged as well, finishing 18 1/2 games behind the first-place Dodgers. Antonelli went 14-16, and was suspended by manager Durocher in early September when he refused to leave the mound leading 3-2 in a game against Philadelphia. In 1956, Antonelli rebounded magnificently, getting elected to his second All-Star Game and winning 20 games for the second time in three years. The Giants, however, did not recover quite as well as their ace and wound up in seventh place.

Antonelli does not keep many physical remembrances of his baseball career in his home, but one that he does keep is a three-foot-high trophy given to him by a group of diehard Giants fans who sat in Section Five at the old Polo Grounds. Those fans voted him the team’s most valuable player in 1956, something that he says means a lot to him even today.18

The 1957 season, the Giants’ last in New York, brought Antonelli another All-Star spot, even though he wasn’t dominant at all during the year, which he ended with a 12-18 record. The next year, 1958, was better in that he finished 16-13, but he failed to throw a shutout for the first time since his rookie year and gave up a league-leading 31 home runs — a career high. Then, after a 19-10 record and yet another All-Star appearance in 1959,19 Antonelli imploded.

In ’59, rumors of Antonelli’s dissatisfaction with the Giants, the media, and San Francisco in general had surfaced, and a year later those rumors proved to be solid fact. After a strong start to the 1960 season, Antonelli’s performance suffered. He was booed mercilessly by Giants fans as tension mounted in early June, and then manager Bill Rigney shocked everyone by ditching the team — with the Giants only four games behind the league-leading Pirates. When the year ended, with the Giants in fifth place and Antonelli just 6-7 and no longer even in the starting rotation, new manager Tom Sheehan proclaimed that the “controversial left-hander” would be dealt soon enough. In the offseason, Sheehan was fired, and replaced with Antonelli’s old teammate, Alvin Dark. Dark, who seemed to truly believe Antonelli was a great pitcher, promised to do all he could to keep “the stylish southpaw.”20 But shortly after, Johnny and Willie Kirkland were traded to the Cleveland Indians for Harvey Kuenn.

For Antonelli, these later years with San Francisco bear certain similarities to his early career with the Boston Braves. Playing outside his home state, in a setting that was unfamiliar to him, Antonelli had found himself in a new environment where he had trouble adjusting. Thousands of miles from his hometown, he began to reach the end of his rope, and the Cleveland Indians became convinced that the only thing wrong was his unhappiness with San Francisco. His dissatisfaction with that west coast city was a sentiment that had been shared by his teammates in the Bay Area,21 and the tension in the clubhouse was compounded by the fact that Johnny had been moved to the bullpen for the first time since his rookie year. Expectations were high for Antonelli, and when he started to fail to meet them, the media was quick to pounce on him as a primary cause for the Giants’ failures.22 Antonelli, for his part, drew the “undying wrath of fans when he grumbled about the wind [in San Francisco].”23 Even today, his strong feelings of discomfort are noted and remembered in the Bay Area:

The Giants played at Seals Stadium for two seasons, now fondly remembered by everybody but Johnny Antonelli, the San Francisco pitcher who disliked the place, said so and was roundly booed, a New Yorker on the wrong coast.24

In any case, executive Bob Kennedy of the Indians, who had taken a keen interest in Antonelli and brokered the trade, was left with the assumption that the left-hander’s discomfort in San Francisco was the only reason he had faltered the year before. Kennedy was confident Antonelli would return to form as soon as given a chance to do so in a place where he could feel comfortable. But the high hopes at the start of 1961 turned to disappointment when Johnny entered May with a 0-4 record. He was soon dealt to the Milwaukee Braves. His impact on the Braves was minimal, and he played in just nine games winning once. In October, Antonelli was sold to the expansion New York Mets, but rather than play for a team that promised to be one of the worst in major league history, Antonelli famously decided to retire from baseball for good. “I quit baseball because I didn’t like traveling,” Johnny said in 2007. “Not for any other reason. I had no injuries or anything. I’d had my fill of traveling. I had a business to fall back on or else I would have played longer, I’m sure.”25

After retirement, Antonelli worked at his tire distributorship back home in Rochester. He was never again involved in organized baseball, though some have confused him with another John Antonelli, an infielder who played in 1944-45 for the Cardinals and Phillies and later managed in the International League. For a time, pitcher Johnny did serve on the board of directors of the Rochester Red Wings, and the two Antonellis met once at an IL game in the city. Neither a fisherman nor a hunter, Johnny enjoyed an active game of golf and is a longtime member of Rochester’s noted Oak Hill Country Club.

The Antonellis had three daughters and one son. Their daughters were a schoolteacher/homemaker, a vascular nurse, and a homemaker, and their son (after working for the family business) became an executive with Starbucks who helped open stores in Europe and the Far East. As of October 2007, Johnny has 11 grandchildren and one on the way and one great-grandchild with another on the way.

Rosemarie Antonelli died in 2002. Johnny remarried in 2006 and he and his wife, Gail, enjoyed traveling together. “I enjoy it, but when you play ball, you stay in a hotel or you go to the ballpark and you never see much of the sights because you’re playing ball. Now I’m seeing sights,” he said.

Johnny Antonelli died at the age of 89 on February 28, 2020, in Rochester, New York.

Notes

1. Interview with Johnny Antonelli by Alex Edelman on March 11, 2007. Additional information in this biography comes from a brief interview by Bill Nowlin on October 24, 2007.

2. Sport Pix, June 1949

3. Total Baseball, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Baseball

4. Letarte, Richard H. That One Glorious Season. (Portsmouth NH: Peter Randell Publishers, 2006)

5. Letarte, op. cit.

6. Christian Science Monitor, June 30, 1948

7. The Sporting News, July 7, 1948, p. 6

8. Total Baseball

9. Cooper, Heath remarks in The Sporting News, 7/14/48, p. 13. Heath’s Feller reference is ironic, because in the aforementioned SportsPix article, Gus Antonelli referred to his son as “a left-handed Feller.”

10. The Sporting News, 5/11/49, p.11. Birtwell, Roger. “Braves Try Out Bonus Kid and Get Man-Sized Hill Job.”

11. The Sporting News, 3/4/53, p. 24. Antonelli was allergic to feathers in pillows, apparently something that had previously caused him to miss a start with the Braves.

12. Pitoniak, “Reluctant legend Antonelli being honored,” Rochester Democrat and Gazette, January 25, 2004.

13. In the All-Star Game, Antonelli pitched in relief, giving up three runs in an NL loss.

14. Marazzi, Baseball Players of the 1950s.

15. Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter (2004 Annual Reunion edition), p. 5. The Pitoniak article also describes this point.

16. It is one of the greatest curiosities in baseball history…How did the Giants (89 wins) beat the mighty Indians (110 wins) in such a dominant fashion? Many attribute it to the brilliant catch of Willie Mays in Game One. A little-known fact, mentioned by Antonelli in an interview with the Boston Braves Historical Association and its members, is that the Indians and Giants, who trained near each other in Arizona, played together 18 times during Spring Training — with the Giants usually coming out on top. Thus, many Giants pitchers were well acquainted with their AL opponents. (Antonelli interview with BBHA, 10/10/2004)

17. Pitoniak.

18. Author interview with Antonelli.

19. Actually, in 1959, baseball held two All-Star Games. Antonelli was elected to both.

20. The Sporting News, “Dark Tosses Cold Water on Rumors of Antonelli Swap”, Jack McDonald, August 1, 1960. It is worth noting that Dark was kind to Antonelli during the uproar surrounding his large bonus. In The Sporting News article chronicling the reactions of players to the bonus, Dark’s was one of the few kind comments. He said he hoped Antonelli would “get more.”

21. The Sporting News. “All Giants Want To Be Traded, Says Long” by Young, Dick. August 31, 1960.

22. Los Angeles Mirror-News, by Charlie Park, August 17, 1960.

23. “Notes: Bochy sticks by Benitez.” MLB.com. Chris Haft, 5/30/2007

24. San Francisco Chronicle, “Baseball Has Been Big-Time in S.F. Since the ’30s,” Carl Nolte, April 11, 2000. The Chronicle comment isn’t entirely true, Antonelli’s dislike for Seals Stadium was minimal; it was the ballpark the Giants moved to in 1960, Candlestick, and the wind in the Bay Area that agitated him so much.

25. Interview with Johnny Antonelli, October 24, 2007.

Full Name

John August Antonelli

Born

April 12, 1930 at Rochester, NY (USA)

Died

February 28, 2020 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.