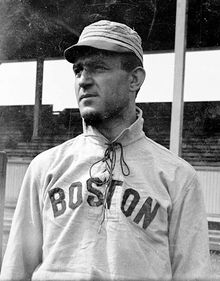

Ed Abbaticchio

For someone who participated in only 855 major-league games spread over nine seasons, Ed Abbaticchio has had more questions raised about his life than most baseball fans might expect. Was he the first Italian American big leaguer? Was he the first professional dual-sport athlete? Was he the creator of the spiral punt? Why did he temporarily retire from Organized Baseball after the 1905 season? Why did the Pittsburgh Pirates trade three veteran players for him on December 11, 1906, when he had not seen any action in the majors or minors since October 7, 1905? Did he receive a higher salary than Honus Wagner in 1907? How did he become part of an urban legend? And how is his last name pronounced? But the answers to these questions are what give shape and color to Abbaticchio’s life, a life as diverse as it was fascinating.

For someone who participated in only 855 major-league games spread over nine seasons, Ed Abbaticchio has had more questions raised about his life than most baseball fans might expect. Was he the first Italian American big leaguer? Was he the first professional dual-sport athlete? Was he the creator of the spiral punt? Why did he temporarily retire from Organized Baseball after the 1905 season? Why did the Pittsburgh Pirates trade three veteran players for him on December 11, 1906, when he had not seen any action in the majors or minors since October 7, 1905? Did he receive a higher salary than Honus Wagner in 1907? How did he become part of an urban legend? And how is his last name pronounced? But the answers to these questions are what give shape and color to Abbaticchio’s life, a life as diverse as it was fascinating.

Born on April 15, 1877, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, Edward James Abbaticchio was the sixth of nine children of Italian immigrants Archangelo Rafaelle Abbaticchio and Maria Filomena Sorrentino.1 The son of a grocer,2 Archangelo, who claimed that his place of birth was Lecca (probably a misspelling for Lecce),3 was a barber who married Maria, a native of Castellammare (currently Castellammare di Stabia), in 1868 and had five children by her before leaving Italy.4 But when he left Italy is another matter. In a letter published in the December 19, 1952, issue of the Latrobe Bulletin, Archangelo’s daughter Pauline wrote that her father immigrated to the United States in 1873 and then sent for Maria and four of their children in 1875,5 and this is the commonly accepted story.6 However, on a passport application in 1910, Archangelo had typed, or had someone type for him, that he had departed from Italy on July 16, 1875. And even though the month and day are obviously wrong because there is newspaper evidence proving that he was already living in the United States by February 17, 1875, the year is supported by data found in both the 1900 and 1910 Federal Census records.7 As for Maria and the four children, the passenger list for the ship Olympia shows them arriving in New York City on December 23, 1875.8

Once in the States, Archangelo traveled to Latrobe, Pennsylvania, where he was subsequently joined by his wife and children and where the Benedictine monks of the Saint Vincent Archabbey assisted him in establishing a barbershop.9 This business enterprise would serve as a launching pad for a series of such shops that he would eventually open in three southwestern Pennsylvania counties.10 But Archangelo did not limit himself to cutting hair. At least as early as 1882, he began purchasing a number of residential and commercial buildings, including a hotel in Latrobe, of which he became the proprietor on April 1, 1889.11

In addition, in Latrobe Archangelo had four more children by Maria, the first of whom was Ed. Not much information can be found about Ed’s childhood, but it is known that he attended Saint Vincent College during the 1891-1892, 1892-1893, and 1895-1896 academic years, taking classical courses, and that in 1895, he earned a Master of Accounts degree from St. Mary’s College (now Belmont Abbey College) in North Carolina.12

When and why Ed became interested in sports is anyone’s guess. However, by 1894, he was in the lineup of the Latrobe baseball town team.13 Then, beginning in 1895 and continuing through the 1900 season, he could be found playing football for the Latrobe YMCA, later referred to as the Latrobe Athletic Club, which in 1897 fielded an all openly professional team.14 And although he would be best remembered for his exploits on the diamond, he thrived on the gridiron. As a fullback, placekicker, punter, and kickoff and punt returner, Abbaticchio developed into one of the stars for the Latrobers and helped his club to achieve 40 victories and compile a .723 winning percentage.15 Some of his personal highlights were

- scoring all his team’s points in Latrobe’s victories over West Virginia University in 1896, the Duquesne Country & Athletic Club in 1900, and archrival Greensburg also in 1900;

- rushing for two touchdowns, being the key blocker on a teammate’s 60-yard run for a touchdown, and kicking seven extra points and a field goal in a defeat of the Pittsburgh Athletic Club in 1897;

- and booting the decisive extra point for a close win over Greensburg in 1898.16

In fact, he performed so well in 1897 that when a Pittsburgh sports expert selected a western Pennsylvania all-star team from the amateur, college, and professional players in the area, he chose Abbaticchio as his fullback.17

Abbaticchio’s prowess with the pigskin, however, led to the first controversy surrounding his name. According to sportswriter and notable college football historian Allison Danzig, “[Fielding] Yost[, the renowned college football coach,] was quoted as saying that the first person he ever saw kick a spiral punt was Eddie Abbaticcho [sic], a professional player, at Latrobe, Pennsylvania, in 1906.”18 But unfortunately for Yost, his words have gotten distorted over the years to say that he credited Abbaticchio with being the first person to kick a spiral punt, something that he never claimed.19 Furthermore, it is generally believed by college football historians that Princeton star Alexander Moffat was the real inventor of the spiral punt during the first half of the 1880s, though it is possible that sometime later Abbaticchio discovered for himself the technique of lofting such a punt. As for the date that Yost observed Abbaticchio’s punting skills, it is more likely that he witnessed them on November 13 and/or 14, 1896, when West Virginia University, where Yost was a student and a member of the football team, played back-to-back games against Latrobe in Latrobe, than in 1906.20 West Virginia and Latrobe clashed another time when Yost and Abbaticchio would have been on opposite sides of the line of scrimmage, but that game was not held in Latrobe.21

Without giving up his football career, Abbaticchio became a member of the Greensburg Athletic Association’s baseball club in either 1896 or 1897.22 This, in turn, led to his being signed to a contract by the Philadelphia Phillies on September 2 of the latter year and making his big-league debut with them as a second baseman against the Cleveland Spiders on September 4.23 But two days thereafter, he broke a bone in his right hand when he crashed into Cleveland catcher Chief Zimmer while attempting to score and was sidelined for the rest of the season.24 Yet, Abbaticchio’s brief stint in a Phillies uniform opens the door to two more controversies surrounding his name: Was he the first Italian American major leaguer? And was he the first professional two-sport athlete? Because of a lack of conclusive evidence, neither controversy can be unequivocally resolved, though from the information available, it is possible to determine with a reasonable degree of accuracy answers to these questions.

Regarding the former matter, the extensive research of Lawrence Baldassaro, supplemented by that of Charlie Bevis, Angelo Louisa, and others, shows that the definitions of “Italian American” and “major leaguer” are critical. If a person needs to have just one parent of Italian descent to be considered an Italian American, and if a major leaguer is anyone associated with major-league baseball, then, in all likelihood, Nicholas Taylor Apollonio, not Edward James Abbaticchio, was the first Italian American major leaguer. Apollonio, the son of an Italian American father and an English-born mother, served as the president of the Boston club of the National Association in 1874 and 1875, and again in 1876, when it became part of the National League (NL).25 But if a person needs to have both parents of Italian descent to be considered an Italian American, and/or if a major leaguer refers to only a player, Apollonio would be disqualified and Abbaticchio would probably take his place. Of course, as Baldassaro has written, “[s]ince so many Italian immigrants changed their names . . . to be less ‘different,’ it is impossible to identify with absolute certainty [the initial major leaguer with an Italian heritage].”26 The search is further complicated by the difficulty of finding the ancestry of the mothers of former major leaguers.

As for the second matter, the key word is “professional.” There were other dual-sport athletes, not to mention those who went beyond participating in two sports, who were living in countries outside of the United States before and/or at the same time that Abbaticchio was playing, but it appears that they were not getting paid for more than one sport, if they were getting paid at all. Nor does it appear that there were any American athletes prior to September 4, 1897, who were receiving money to play more than one sport.27 Thus, unless a better candidate is found in the future, Abbaticchio is arguably the first professional two-sport athlete. In fact, he added a third sport to his repertoire when he became a member of the Greensburg basketball club in December of 1898, though Louisa has not discovered if the club was amateur, semiprofessional, or professional.28

Also in 1898, Abbaticchio saw action in 25 games with the Phillies before embarking on a four-year career in the minor leagues after Philadelphia loaned him to the Minneapolis Millers of the Western League in 1899.29 During this odyssey, “Abby” (“Abbey,” “Abbie”) or “Batty” (“Battie”), as Abbaticchio became nicknamed, played for Minneapolis in 1899, for Minneapolis and the Milwaukee Brewers, both of the American League (the former Western League), in 1900, and for Nashville, which had no official moniker at that time, of the Southern Association in 1901 and 1902.30 While with the Millers in ’99, he scored 81 runs, stole 32 bases, and led the league’s second basemen in putouts, total chances, chances accepted, total chances per game, and range factor per game.31 While with the Brewers, he was managed by Connie Mack, who thought enough of Abbaticchio’s skills to twice attempt to purchase him from Nashville for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1902.32 But it was with the Nashvilles—as the club was sometimes unofficially labeled—that he had his finest seasons.

Batting .363 with 39 stolen bases and a league-leading 127 runs scored in 1901 and hitting .353 with 96 runs scored and a league-leading 18 triples the following season, Abbaticchio was one of the stars who propelled the Tennessee franchise to back-to-back pennants.33 And though largely forgotten today, his performances on the field were so good that even as late as 1948 “[s]ome old timers [sic] [said that he was] the best all-round keystoner ever to operate in the Southern Association.”34

Off the field, Abbaticchio was equally successful in Nashville, meeting saleslady Anne Connor, the daughter of an iron moulder, and eventually marrying her on October 28, 1903. The marriage led to the couple having three boys and four girls. Of those seven, one daughter died of intestinal poisoning at the age of three and another was stillborn, but from the remaining five offspring came two nurses, a physician who taught at Yale University, a federal government employee, and a Benedictine priest.35

In addition, during his stay in Nashville Abbaticchio provided the answer to a question that has perplexed readers who did not know him: How did he pronounce his last name? The standard Italian way would be Ab-ba-TEE-kee-o, but that is not how Abbaticchio pronounced it. Nor did he pronounce it Ab-ba-TEESH-i-o. As he told a sportswriter, “The correct way is Ab-bat-ti-ko, with the accent on the second syllable.”36 Of course, printing his name in newspaper box scores presented another challenge, so “Abbaticchio” appears contracted as “A’chio,” “Ab’io,” “Ab’t’o,” and “Abb’o,” among other abbreviated versions.

Despite enjoying his time in the Athens of the South, Abbaticchio’s days there were numbered. His baseball accomplishments in ’01 and ’02 did not go unnoticed by major-league clubs besides the Philadelphia Athletics. In particular, they caught the eye of the National League’s Boston Beaneaters, who bought the second sacker with the strange name for $1,500, the equivalent of $306,000 in 2018,37 in September 1902.

Abbaticchio was delighted to return to the big show, though his happiness was diminished by having to adjust to major-league pitching, as evidenced by his hitting .227 in 1903 when the entire NL averaged .269. But he was a quick learner, and the next season, he batted .256, seven points higher than the league’s mark of .249, and finished ninth in hits. These statistics Abbaticchio topped in 1905, his best offensive season with the Beaneaters, when he raised his batting average to .279, 24 points greater than the league’s .255, and ended up in the NL’s top 10 in hits, singles, doubles, extra-base hits, total bases, and stolen bases. Applying the Offensive Wins Above Replacement (oWAR) formula to those numbers shows Abbaticchio to be ranked ninth among batters in the senior circuit.

Defensively, Boston’s new second baseman committed 45 errors in 116 games in 1903, but he covered a lot of ground and handled a number of chances cleanly. And possibly because of the last two factors, Beaneaters manager Al Buckenberger moved him from second base to shortstop in 1904, and Fred Tenney, Buckenberger’s successor as Boston’s manager in 1905, kept him there for that season. The results were predictable: for both years, Abbaticchio led National League shortstops in errors as well as finishing in the top three for his position in putouts, assists, total chances, chances accepted, total chances per game, and range factor per nine innings for ’04 and putouts, total chances, and total chances per game for ’05.

By the fall of 1905, Batty, as Abbaticchio preferred to be called, was 28 years old and had established himself as a major leaguer. Though no superstar, he was a team player, able to win and keep a starting spot on a club at the highest level of Organized Baseball, even if it was a club that had been stuck in the second division since he had joined it. True, he made a lot of fielding errors, but he was getting to balls that the majority of middle infielders were not, and no one doubted that he could contribute to the success of any team with his bat. So, many people were surprised when it became publicly known in January of 1906 that the successful Italian American was retiring from Organized Baseball to become the proprietor of his father’s hotel, the Latrobe House. The exact reason for this decision is unclear. “Close friends of the [Abbaticchio] family” claimed that Archangelo, who had been desiring to leave the hotel business, had “offered . . . [his] fine hotel” to Ed as an inducement to get his son to stop playing professional baseball, something that Archangelo was against.38 Another possibility is that the financially shrewd Ed—remember that he had earned a Master of Accounts degree and had an entrepreneurial father as a role model—engineered the entire scenario himself to escape from playing for a losing ballclub and to be traded to one of the National League powers. Or perhaps Ed was trying to find out how much his baseball skills were worth.

Whatever the reason, Ed became Archangelo’s successor as the owner of the Latrobe House, and by doing so, he either inadvertently or purposely started a bidding war among several senior circuit clubs which attempted to lure him back to the diamond. The Beaneaters initially made him two offers—$3,000 and $3,200—to maintain his services, while the New York Giants, Pittsburgh Pirates, Chicago Cubs, and Cincinnati Reds all showed an interest in acquiring him, with the Giants and Pirates receiving permission from Boston to negotiate with him.39

Abbaticchio’s reaction to the attention he was receiving was to play hard to get. At first, he told anyone who approached him that he was through with professional baseball, though he was quick to show the Pirates and Cubs players assembled for a series at Exposition Park in early May a piece of correspondence that he had received from Giants manager John McGraw. In it, the Little Napoleon had written in part, “I . . . would be pleased to meet with you in regard to signing a contract with New York,” something that Abbaticchio said he would consider.40 But around the same time, Abbaticchio informed Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss that if he were to return to the majors, it would be with the Bucs because Pittsburgh was close enough to Latrobe to allow him to rejoin Organized Baseball and still run his hotel.41

Then, in late June, late July, and early December, more intrigue was added to the story. On June 26, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that Abbaticchio had been sent “a mysterious letter” which his close friends said came from the Giants, Pirates, or Cubs and which motivated him to start playing baseball again for the Latrobe town team.42 This development was followed by John McGraw and Giants owner John Brush visiting Latrobe on July 22 and presenting Abbaticchio with a two-year contract for a total of $12,000, an offer that Abbaticchio rejected.43 And finally, on December 1, the Pittsburgh Press published a statement about Abbaticchio made by George Dovey, the head of a syndicate that had purchased Boston’s National League franchise three days earlier. Like McGraw and Brush, Dovey had gone to Latrobe to talk with the unsigned infielder, and he came away saying, “[Abbaticchio has] been so successful in business that . . . I doubt very much indeed if he will ever return to the game.”44

Yet, only 10 days later, Boston traded Abbaticchio to Pittsburgh for second baseman Claude Ritchey, pitcher Patsy Flaherty, and a player to be named later, who turned out to be center fielder Ginger Beaumont. Ritchey and Beaumont were popular Pirates who had helped their club win three pennants and come in second twice within a seven-year period. Flaherty had spent the 1906 season with the Columbus Senators of the American Association but had had a career year with the Bucs in 1904. Thus, Pirates fans in general were not enamored with the trade, and some people wondered why Dreyfuss would give up so much to acquire Abbaticchio. There was even a rumor that the Pirates owner purposely overdid it to help George Dovey, who was one of his close friends.

Be that as it may, the primary motivation for Dreyfuss’ decision appears to have been two-fold: the perception of Abbaticchio by knowledgeable baseball personages at the time and Dreyfuss’ hatred for John McGraw. For example, when William Conant, one of the two magnates running the Boston franchise before the sale to Dovey et al., realized that Abbaticchio was not returning to the Beaneaters, he lamented, “[W]ith him[,] we could cut a big figure in the championship race. . . . He is a mighty good man and the club that secures him will get a star player.”45 Or after the trade had been made, future National Baseball Hall of Famer Hugh Duffy proclaimed, “The acquisition of ‘Batty’ certainly puts the Pirates in the running for the championship. He is a fine player and I am satisfied that his one year’s lay-off [sic] will prove beneficial.”46 Nor were these men alone in their praise of the Latrobe hotel owner. Abbaticchio was a hot commodity in baseball circles in 1906, as evidenced by the relatively large amount of money Brush and McGraw were prepared to give him.

And it was Brush and McGraw’s interest in Abbaticchio that heightened Dreyfuss’ desire to have him. The Giants had displaced the Pirates as the senior circuit’s top dog in 1904 and 1905, and even though both clubs finished behind an outstanding Cubs team in 1906, New York came in second, 3 1/2 games ahead of Pittsburgh. But beyond wins and losses and league standings, Dreyfuss loathed McGraw, an enmity that had begun when the Giants manager had publicly harassed and embarrassed the Pirates owner on May 20, 1905. So, if he could hurt McGraw by hurting the Giants while helping his own club at the same time, Dreyfuss was willing to trade three players he believed had seen better days for a highly touted second baseman-shortstop.

As for Abbaticchio, the transaction left him ecstatic, believing that he had the best of both worlds: he could keep his hotel and resume playing professional baseball. His bubble would burst in 1908, but for the moment he was enjoying life, and this enjoyment carried over to his on-the-field performance for the 1907 season.

Playing the keystone position and usually batting in the fifth slot, Abbaticchio finished in the National League’s top 10 in walks, hit batsmen, stolen bases, and runs batted in; according to oWAR, he was the 10th best offensive player in the NL. Defensively, he was not as effective, leading second sackers in errors, though to his credit, he came in fourth at his position in putouts, assists, total chances, and total chances accepted.

In part because of Abbaticchio’s positive contributions, Pittsburgh moved up to second place in 1907 as the Cubs repeated as pennant winners. But both Abbaticchio and the other Pirates were appalled to learn during spring training of the following year that a Westmoreland County judge had ruled that he would not renew the Latrobe House’s liquor license unless the Bucs second baseman quit playing Organized Baseball.47 Abbaticchio, however, quickly remedied the situation by transferring the ownership of his hotel back to his father,48 raising the question of whether Archangelo was ever against his son being involved with professional baseball.

The 1908 season was one of the most exciting in National League history with Pittsburgh, New York, and Chicago battling it out for the pennant. The Cubs would eventually triumph but not before winning a crucial game against the Pirates that led to Abbaticchio being the center of a modern piece of folklore.

Just a half-game ahead of Chicago and 1 1/2 games ahead of New York, the Pirates faced off against the Cubs at West Side Grounds on October 4. This was Pittsburgh’s last regular-season contest, while Chicago still had a possible replay game with New York—the infamous “Merkle tie”—and the Giants had three games remaining with the lowly Boston Doves, the former Beaneaters, plus the possible replay game with Chicago. Thus, if the Pirates had defeated the Cubs that day, they would have eliminated Chicago from pennant contention and pressured New York to sweep Boston and then knock off Chicago to force a playoff. But such was not to be. Behind the pitching of Three Finger Brown and a strong hitting attack and aided by two errors by Honus Wagner, the Cubs beat the Pirates, 5-2. This result left the Bucs and their fans having to hope that the Giants would lose at least one game to the Doves and, after that, vanquish the Cubs to create a three-way tie for first place. In reality, New York swept Boston and lost to Chicago, allowing the Cubs to clinch their third pennant in a row.

As for Abbaticchio, he mainly played well for the first eight innings of the October 4 contest, fielding flawlessly and driving in one of Pittsburgh’s two runs. Then, in the top of the ninth, with the Pirates down by three, Wagner led off with a single to center. Abbaticchio followed him to the plate and launched a shot into the overflow of fans standing in an area of right field that consisted of both fair and foul territory. The Bucs argued that the ball was fair and, hence, the hit was a double according to the rules in use that day; the umpires—Hank O’Day, who made the initial call, and Cy Rigler, who agreed with him—declared that it was foul; and, of course, the umpires’ decision was final. So, Wagner returned to first base and Abbaticchio went back to the plate, where he proceeded to strike out. Two force outs later, the game was over, and that should have been the end of the story, but it was not. Instead, Abbaticchio’s name and his hitting of the controversial foul ball became confused with or was purposely combined with an incident that happened in 1911, causing a new story to emerge, which was exaggerated as the years went on. Here are the details:

- On January 5, 1912, Sam Weller of the Chicago Tribune reported that the previous day Ruby Florsheim had filed a suit against the Chicago Cubs for $10,000 because she claimed that she “was hit on the head . . . and severely injured” by a foul ball that went into the grandstand at West Side Grounds during a game between Chicago and the Cincinnati Reds on September 10, 1911.49 Charles Williams, the Cubs treasurer at that time, countered the allegation when he told Weller, “As I remember, Miss Florsheim came to me after the game and said she had been hit on the leg by a foul ball and that it had caused a black and blue spot. I didn’t think it was anything serious and joked with her about it.” 50

- Versions of Weller’s article appeared in at least eight other newspapers, six of them outside of Illinois.

- On September 14, 1913, more than 20 months after Weller’s piece saw the light of day, sportswriter James Jerpe’s column in Pittsburgh’s Gazette Times contained a section which in part read: “Mrs. Ruby Florsheim, a Chicago woman some time ago sued the Chicago baseball club for $10,000 damages for injuries sustained on Sunday, October 4, 1908, when she was hit on the knee by a batted ball, said ball being batted by Edward Abbaticchio, then a member of the Pittsburgh baseball club.”51 The section went on to describe the action in the top half of the ninth of that game, but it contains several additional mistakes, including that there were runners on first and second when Abbaticchio was batting.52 Thus, it appears that Jerpe mixed up the details of the Florsheim case with Abbaticchio’s at-bat or decided to be creative and produced a fictionalized account of what had happened, but either way, a myth was born.53

- This myth was later distorted by other sportswriters who provided their own degree of drama to it. For example, in his May 3, 1952, column, Al Grady, the sports editor of the Iowa City Press-Citizen, penned a retelling so chock-full of errors as to be hilarious:

. . . when the Cubs and Pirates met on the last day of the season in Pittsburgh, a victory would have given the Pirates the pennant.

True to the Frank Merriwell kind of finish, the Pirates trailed in the last half of the ninth, but loaded the bases and a strong young kid by the name of Ed Abbaticchio strode up to the plate.

After some delay, Abbaticchio teed off on one and hit it a mile into the left field stands right at the foul line as the Pirate fans went crazy.54

And concerning Ruby Florsheim and her complaint:

A female Pittsburgh fan brought suit for damages against the Pirate ball club. . . .

. . . [after which,] some Pirate official took [her] ticket stubs . . . and went out to the ball park [sic] to see where [she] had been sitting.

Much to his dismay, he found her seat was the first one INSIDE [Grady’s emphasis] the foul pole.55

- In 1965, the creator and former editor-in-chief of Baseball Digest, sportswriter Herbert Simons, and the Baseball Digest staff investigated the tale and found nothing to support it. As Simons wrote:

A thorough, tedious search of all official records of all state and county courts in Chicago for two years following the game (after which the statute of limitations would preclude such a suit) failed to reveal any such lawsuit filed against the Cubs (in fact, no lawsuit against the Cubs by any fan). A day-by-day search of the Chicago newspapers from the morning after the game until well into 1911 failed to disclose any mention of any such legal action. [Because the researchers did not look at Chicago newspapers from 1912, they did not find Sam Weller’s article.]

[Whereas] 1908 legal records of both [the] Chicago and Pittsburgh clubs have been lost in antiquity, no official of either club could recall ever having heard any mention of any such suit.56

Yet, even as late as 2015, a reputable reference work on the Pirates contained a version of the tale, proving that myths die hard.57

Leaving aside the frustration of the October 4 game, Abbaticchio could look back on the 1908 season with satisfaction. He finished in the top 10 among National League hitters in walks and runs batted in, and he became a much less erratic fielder, leading the senior circuit’s second basemen in fielding percentage, in addition to coming in second in assists, tied for third in double plays, and fourth in putouts.

The next season, however, proved to be bittersweet for the veteran infielder. On the one hand, he lost his starting job to 22-year-old Dots Miller and was relegated to being a utility man who saw action in only 37 games.58 On the other hand, he got to be a member of a great Pirates team that won 110 regular-season games and the World Series championship, and he did an excellent job of subbing for Honus Wagner at shortstop. He even made an appearance as a pinch-hitter for pitcher Deacon Phillippe in the ninth inning of Game Six of the Fall Classic, though here, too, his experience was bittersweet as he struck out with two men on base and the Bucs trailing by one run.

With Miller firmly established at second base and another young man, Bill McKechnie, joining the Pirates as a new utility infielder in 1910, Abbaticchio became expendable and was released by Pittsburgh on June 20 of that year.59 Shortly thereafter, he was claimed by his former Boston club, for whom he participated in 52 games prior to his being released again, this time on September 17.60

The months that Abbaticchio spent with the Doves were his last hurrah in Organized Baseball. In 1911, he signed a contract with Louisville of the American Association but reneged after buying a hotel near Forbes Field, something that he had told the Louisville management he might do when he accepted the offer.61

In 1914, Abbaticchio sold his Pittsburgh hotel, and by September 12, 1918, he was working as a manager for his father, presumably at the Latrobe House.62 This was followed by his regaining the ownership of his father’s hotel on November 13, 1920, when Archangelo stepped down in advance of his moving to Washington, D.C.63

During the 1930s, Abbaticchio retired to Florida, where he died from cancer on January 6, 1957.64 His body was then sent back to Pennsylvania and buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery in Latrobe four days later.65 However, less than five years before his death, the elderly former Pirate started a myth about himself when he told Dick Meyer, the sports editor of the Fort Lauderdale Daily News, that he had a higher salary than Honus Wagner in 1907: $5,000 to the Flying Dutchman’s $4,000.66 And despite the fact that the claim sounds unbelievable, it was accepted at face value and repeated in various secondary writings.67 But the truth of the matter is that though Angelo Louisa has not been able to confirm the amount of money that Abbaticchio was being paid in 1907,68 several baseball historians have discovered that Wagner earned $5,000, not $4,000, that year.69 So at best, Abbaticchio received the same salary as Wagner, which is impressive enough, provided, of course, that the 75-year-old’s memory was correctly recalling what Barney Dreyfuss gave him.

A man whose life was filled with controversies, Edward James Abbaticchio was a versatile athlete, a well-educated hotel owner, and an Italian American trailblazer. His baseball credentials are not strong enough to get him inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Nor is it likely that he will ever be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. But in the words of Lawrence Baldassaro, “[he] deserves to be remembered as more than a historical footnote.”70

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Most sources agree that Archangelo and Maria had nine children, of which Ed was the sixth, with the birth order being: Nicholas (1869-1955), Albert (1870-1958), Pauline (1871-1957), Arthur (1872-1875), Horace (1874-1970), Edward (1877-1957), Caroline (1878-1962), William (1880-1979), and Raymond (1882-1959). However, on Ancestry.com, there are family trees for Archangelo or Maria that mistakenly allege that the couple had an illegitimate daughter named Mary, who was born in 1864 and died sometime after the 1880 United States Federal Census was taken. And the origin of this error appears to be the 1880 Federal Census itself, which lists a 16-year-old girl named Mary as part of the Abbaticchio household and does not provide her with a different last name but states that her relationship to the head of the household was that of a servant. This confusion is an obvious misreading because the Abbaticchio children are listed by age in descending order with a straight line to the left of the child’s first name to indicate that his or her last name was the same as that of the head of the household. Conversely, Mary, who was older than all the children, is listed last and does not have a straight line near her name. See 1880 United States Federal Census. Also on Ancestry.com, there are family trees that maintain Archangelo’s first name was Damian and that his middle name was Archangelo, but Angelo Louisa could not find any evidence to support this claim.

2 John Newton Boucher, History of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, Vol. 2 (New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1906), 272.

3 Depending on the source, Archangelo was born in Betonto (probably a misspelling of Bitonto), Castellammare, or Lecca (probably a misspelling of Lecce), but on a passport application that he signed in 1910, he swore that his place of birth was Lecca. See “U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925,” https://www.ancestry.com (accessed on April 28, 2018). In all likelihood, Archangelo used the Italian pronunciations of “i,” which sounds like the English “e” in “tea” or “i” in “machine,” and “e,” which sounds like the English “e” in “bet” or the “a” in chaos. But when these sounds were transcribed by someone who may not have been familiar with the Italian language, they were written incorrectly. Hence, “Bitonto” becomes “Betonto” and “Lecce” becomes “Lecca.”

4 Boucher, 272, and “Genealogical Chart of Abbaticchio-Sorrentino and Descendents,” Abbaticchio Family File, Latrobe Area Historical Society, Latrobe, Pennsylvania.

5 “Plucky Mother Played Part in Bringing Abbaticchios to USA,” Latrobe Bulletin (Latrobe, Pennsylvania), December 19, 1952. Pauline’s dates are supported by the family tree that her brother William compiled. See “Genealogical Chart of Abbaticchio-Sorrentino and Descendents,” Abbaticchio Family File, Latrobe Area Historical Society, Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Arthur had died earlier that year, so the four children who came with Maria were Nicholas, Albert, Pauline, and Horace.

6 For examples of secondary works that use Pauline’s dates, see Lawrence Baldassaro, “Ed Abbaticchio: Italian Baseball Pioneer,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Social Policy Perspectives 8, no. 1 (Fall 1999): 19; Lawrence Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 4; and “Ed Abbaticchio: Italian-American Sports Pioneer,” The Latrobe Historical Gazette (Spring 2013): 1.

7 The immigration year for Archangelo given in the 1920 Federal Census is 1873, but by 1920, Archangelo and Maria were in their late 70s and may not have been as lucid as they were in 1900 and 1910. Cf. “U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925”; “McBride & Abbaticchio’s Fancy Hair Dressing, Curling and Shaving Saloon, Ligonier Street, Latrobe, Pa.,” Latrobe Advance (Latrobe, Pennsylvania), February 17, 1875; 1900 United States Federal Census; 1910 United States Federal Census; and 1920 United States Federal Census.

8 “New York, Passenger and Crew Lists (Including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957,” https://www.ancestry.com (accessed on April 29, 2018). In addition, it is interesting to note that the 1920 Federal Census again muddies the water by stating that Maria emigrated in 1874, which supports the possibility that Archangelo’s and Maria’s memories were failing when they talked with the census taker. See 1920 United States Federal Census.

9 Archangelo initially shared a salon with H. J. McBride before starting his own place of business. “Plucky Mother Played Part in Bringing Abbaticchios to USA”; “McBride & Abbaticchio’s Fancy Hair Dressing, Curling and Shaving Saloon, Ligonier Street, Latrobe, Pa.”; and Untitled article, Latrobe Advance, February 24, 1875. There are conflicting stories as to why Archangelo journeyed to Latrobe. Cf. Boucher, 272, and “Plucky Mother Played Part in Bringing Abbaticchios to USA.”

10 Boucher, 272.

11 Boucher, 272-273, and “A Business Change,” Latrobe Advance, December 12, 1888. For several examples of what else Archangelo owned, see Untitled article, Latrobe Advance, December 13, 1882; “Minor,” Latrobe Advance, November 28, 1883; “Minor,” Latrobe Advance, January 30, 1884; and “Latrobe Hotel Man Has Abolished the Back Room,” Latrobe Bulletin, April 2, 1906.

12 “Father Damian’s Family Tie to Baseball Pioneer,” https://www.saintvincentarchabbey.org/2001/03/16/father-damians-family-tie-to-baseball-pioneer (accessed on April 29, 2018), and Edward J. Abbaticchio, Diploma, Master of Accounts, St. Mary’s College, found in Ed Abbaticchio, Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

13 “All Suffered Defeat,” Indiana Progress (Indiana, Pennsylvania), August 1, 1894.

14 The football club has also been referred to as the Latrobe Athletic Association, but that name was not used until after the 1900 season.

15 Robert B. Van Atta, “Latrobe, Pa.: Cradle of Pro Football,” The Coffin Corner 2 (1980): 20.

16 “Great Is Latrobe,” Pittsburgh Post, November 14, 1896; “Kicks a Goal from the Field,” Pittsburgh Post, November 11, 1900; “Abbaticchio Again the Hero,” Pittsburgh Post, November 18, 1900; “No Less Than an Avalanche,” Pittsburgh Post, November 7, 1897; and “One Kick Saved Latrobe,” Pittsburgh Press, November 6, 1898.

17 Van Atta, 8.

18 Allison Danzig, The History of American Football: Its Great Teams, Players, and Coaches (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1956), 116.

19 Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball, 6.

20 “Great Is Latrobe,” and “Another Close One at Latrobe,” Pittsburgh Post, November 15, 1896.

21 “Morgantown Wins from Latrobe,” Pittsburgh Post, October 20, 1895.

22 There was an Abbaticchio who played at least several games for the Greensburg Athletic Association in 1896, but it is not clear if it was Ed. It may have been his brother Horace. See “Derry Team Swiped,” Greensburg Daily Tribune (Greensburg, Pennsylvania), June 18, 1896; “Kensington a Little Light,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, August 20, 1896; and “Jeannette Must Feel Tired,” Pittsburgh Post, August 30, 1896. However, Ed definitely played for Greensburg in 1897. See “Base Ball Notes,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), September 3, 1897, and “Favors the Change,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, January 22, 1898.

23 “Favors the Change”; “Phillies’ New Infielder,” Chicago Tribune, September 3, 1897; “Sporting Tidings,” Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), September 3, 1897; and “Ed Abbaticchio,” https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/a/abbated01.shtml (accessed on March 13, 2019). Although Abbaticchio’s first major-league game was on September 4, 1897, the first time that he played competitively as a Phillie was in an exhibition game against the Media, Pennsylvania, team on September 3, 1897. “Sparks a Bright Light,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1897.

24 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, September 8, 1897.

25 Although Baldassaro and Bevis agree that Apollonio had Italian American genes, Baldassaro writes that Apollonio was the grandson of an Italian immigrant, while Bevis states that Apollonio’s father emigrated from Italy. Supporting Baldassaro are the 1880 United States Federal Census, the 1900 United States Federal Census, and Apollonio’s death certificate, which show Connecticut as the place of birth of Apollonio’s father. As for Apollonio’s mother, the 1880 census reports that she was born in New York, but both the 1900 census and Apollonio’s death certificate indicate that she was born in England. Cf. Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball, 15-16; Charlie Bevis, “Nicholas Apollonio,” https://sabr.org/node/43174 (accessed on May 31, 2018); 1880 United States Federal Census; 1900 United States Federal Census; and “Massachusetts, Death Records, 1841-1915, Nicholas Taylor Apollonio,” www.ancestry.com (accessed on March 14, 2019).

26 Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball, 4.

27 For the names of many athletes who played more than one sport, see “List of Multi-Sport [sic] Athletes,” https://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_multi-sport_athletes (accessed on June 24, 2018). For the names of major-league baseball players who played professional football, basketball, or hockey, see Stan Grosshandler, “Two-Sport Stars,” in Total Baseball, 3rd ed., eds. John Thorn and Pete Palmer with Michael Gershman (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 1993), 237-243.

28 “New Basketball Players,” Pittsburgh Press, December 16, 1898. Also, Louisa has yet to come across anyone asking if Abbaticchio was the first Italian American professional football player. But even if the question has been asked, the problems of defining “Italian American” and “professional” and discerning which names are truly Italian in origin apply here as well.

29 “Base Ball Notes,” Wilkes-Barre Daily News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), August 17, 1899.

30 “Name That Team,” https://www.262downright.com/2013/10/01/486 (accessed on July 15, 2018).

31 “Record of the Western,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1899.

32 Connie Mack to Ed Abbaticchio, telegram, June 11, 1902, found in Ed Abbaticchio, Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York, and Connie Mack to Newt Fisher, telegram, July 2, 1902, found in Ed Abbaticchio, Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

33 Statistics for runs scored and stolen bases were taken from Francis C. Richter, ed., Reach’s Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1902 (Philadelphia: A. J. Reach Co., 1902), 184; Henry Chadwick, ed., Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1902 (New York: American Sports Publishing Co., 1902), 159; Francis C. Richter, ed., Reach’s Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1903 (Philadelphia: A. J. Reach Co., 1903), 201; and Henry Chadwick, ed., Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1903 (New York: American Sports Publishing Co., 1903), 206. Statistics for batting averages and triples were taken from “Ed Abbaticchio,” https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=abbati001edw (accessed on March 13, 2019); “Ed Abbaticchio,” www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/stats/p-e51cc3d1 (accessed on July 22, 2018); and “1902 Southern League Leaders,” www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/leaders/l-SOUA/y-1902 (accessed on July 22, 2018). However, for Abbaticchio’s 1902 batting average, the Stats Crew did not round up from .3525. Some other sources have different batting averages, but their numbers are the results of mathematical or typographical errors or the repetition of such previously recorded errors.

34 Fred Russell, “Sidelines,” Nashville Banner, March 9, 1948.

35 In chronological order, Abbaticchio’s children were Edward (1904-1972), Rose (1906-1910), Catherine (1908-1975), Infant (1911), Howard (1913-1958), Martha (1915-1984), and Albert (1917-2006). Catherine and Martha became nurses; Edward, who changed his last name to Abbey, became a medical doctor; Howard became a federal government employee; and Albert, who joined the Order of Saint Benedict and took the name of Damian, became a priest. Some sources erroneously state that the stillborn daughter’s name was Anne, but the name on her death certificate is Infant Abbaticchio. See Infant Abbaticchio, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966, https://ancestry.com (accessed on November 23, 2018).

36 “Back to the Bosky Dell with ‘Abby’; ‘Batty’ Is the Name to Conjure With,” an undated article from an unknown newspaper found in Ed Abbaticchio, Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

37 “Abbattichio [sic] a Beaneater,” Pittsburgh Press, September 10, 1902. The 2018 value is based on Gross Domestic Product per capita found at https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/uscompare/relativevalue.php (accessed on March 13, 2019).

38 “A. Abbaticchio Is to Retire,” Latrobe Bulletin, January 2, 1906, and “Batty Quits Baseball?” Pittsburgh Post, January 4, 1906.

39 “A Big Offer for Abbaticchio,” an undated article from an unknown newspaper found in Ed Abbaticchio, Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York; “Want ‘Batty’ Badly,” Latrobe Bulletin, March 28, 1906; “Breakfast Food for Fans Served Up Hot,” Altoona Times (Altoona, Pennsylvania), April 14, 1906; “Reds Are After ‘Abby,’” Pittsburgh Press, May 18, 1906; “Base Hits,” Harrisburg Telegraph, June 15, 1906; and “Batty Back Into Game,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 26, 1906.

40 “Abby May Return to Game,” Burlington Daily Free Press (Burlington, Vermont), May 8, 1906, and “Giants After Abbaticchio,” Sun (Baltimore), May 9, 1906.

41 “Giants After Abbaticchio.”

42 “Batty Back Into Game.”

43 “Abbaticchio Gets Offer,” Pittsburgh Post, July 24, 1906, and “Batty Lost to Beanies,” Pittsburgh Press, December 1, 1906.

44 “Batty Lost to Beanies.”

45 “‘Batty’ Likely to Be a Pirate,” Pittsburgh Press, May 16, 1906.

46 “Base Ball Notes,” Evening Star, December 22, 1906.

47 “May Lose Another Player,” Washington Post, March 31, 1908.

48 “Abbaticchio Gets His License,” Gazette Times (Pittsburgh), April 12, 1908.

49 Sam Weller, “$10,000 Ball at Cubs’ Park,” Chicago Tribune, January 5, 1912.

50 Ibid.

51 James Jerpe, “On and Off the Field,” Gazette Times, September 14, 1913.

52 Ibid.

53 Could someone else have created the home run myth before Jerpe did? Perhaps. But after examining a countless number of newspapers, Angelo Louisa has not discovered any evidence of the myth existing prior to Jerpe’s column of September 14, 1913.

54 Al Grady, “Sports of All Sorts,” Iowa City Press-Citizen, May 3, 1952.

55 Ibid. For a comparison of four other versions of the story, see Herbert Simons, “The Line Drive That Was Fair, Foul and Phony,” Baseball Digest 24, no. 8 (September 1965): 13.

56 Simons, 13.

57 David Finoli and Bill Ranier, The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. (New York: Sports Publishing, 2015), 20.

58 Even though the “Batting Record” for Ed Abbaticchio at www.retrosheet.org says that Abbaticchio participated in 36 games, “The 1909 Pit N Regular Season Batting Log for Ed Abbaticchio,” also at www.retrosheet.org, shows box scores where he took part in 37 games, including one as a pinch-hitter and two as a pinch-runner, and Baseball-Reference.com states that he appeared in 37 games. Cf. “Batting Record, www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/A/Pabbae101.htm (accessed on April 20, 2019) ; “The 1909 Pit N Regular Season Batting Log for Ed Abbaticchio,” https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1909/Iabbae1010081909.htm (accessed on April 20, 2019); and “Appearances,” https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/a/abbated01.shtml (accessed on April 20, 2019).

59 “Abby Is Released by the Champions,” Pittsburgh Press, June 21, 1910.

60 “Wants Abbaticchio,” Washington Times (Washington, D.C.), June 21, 1910, and “‘Batty’ Is Released,” Boston Globe, September 17, 1910.

61 “Player Buys Hostelry,” Indianapolis Star, February 14, 1911.

62 “License Court Transfer Cases Nearing Close,” Pittsburgh Press, November 9, 1914, and Edward James Abbaticchio, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, https://www.ancestry.com (accessed on November 23, 2018). In addition, the 1920 United States Federal Census shows Abbaticchio to have been the general manager of the Latrobe House as of January 2, 1920. 1920 United States Federal Census.

63 “A. Abbaticchio Sells His Hotel,” Latrobe Bulletin, November 15, 1920.

64 “Ed Abbaticchio,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1957, 24. As with so many other facets of Abbaticchio’s life, his moving to Florida is not without its share of controversy. The 1937 Miami city directory lists the retiree as living there by then, but when did he arrive? Lawrence Baldassaro wrote that it was 1932, which is not correct because there is an article in the July 6, 1934, issue of the Latrobe Bulletin that shows him residing in Latrobe at that time. The Bulletin’s obituary for Abbaticchio implies that he had been dwelling in Florida since 1942, something that an article in the December 28, 1952, issue of the Nashville Tennessean contradicts by saying that he relocated to the Sunshine State in 1934. Thus, by putting the pieces together, it appears that Abbaticchio arrived in Florida sometime between July 6 and December 31 of 1934. Cf. Polk’s Greater Miami City Directory, 1937 (Jacksonville, Florida: R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1937), 37; Baldassaro, “Ed Abbaticchio: Italian Baseball Pioneer,” 24; Lawrence Baldassaro, “Before Joe D: Early Italian Americans in the Major Leagues,” in The American Game: Baseball and Ethnicity, eds. Lawrence Baldassaro and Richard A. Johnson (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 96; Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball, 10; “Locals,” Latrobe Bulletin, July 6, 1934; “Ex-Football and Diamond Star Dies,” Latrobe Bulletin, January 7, 1957; and Raymond Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion,” Nashville Tennessean, December 28, 1952.

65 “Ex-Football and Diamond Star Dies.”

66 Dick Meyer, “Ed Abbaticchio Recalls Bad Call That Cost Flag,” Fort Lauderdale Daily News, May 13, 1952.

67 For several examples of this repetition, see Chester L. Smith, “The Village Smithy,” Pittsburgh Press, May 22, 1952; Vince Quatrini, “Sports Prints,” Latrobe Bulletin, November 5, 1952; Baldassaro, “Before Joe D: Early Italian Americans in the Major Leagues,” 95; and Lawrence Katz, “Who Was the First Italian American Baseball Player?” F&L Primo 9, no. 2 (April-May 2008): 55. Baldassaro later wrote that Abbaticchio received $800 more than Wagner. See Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball, 9.

68 Baseball-Reference.com lists Abbaticchio’s salary as $5,000, but whoever recorded this information may have taken it from Dick Meyer’s article or from one of the articles or books that used what Abbaticchio had told Meyer. “1907 MLB Player Value,” https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/1907-value-batting.shtml (accessed on March 12, 2019). Also, an article in the March 31, 1908, issue of the Washington Post reported that Abbaticchio had “a $3,000 job” going into the 1908 season, which obviously was $2,000 less than what Abbaticchio claimed he had earned in 1907. Thus, if the Post was correct, this disclosure implies either Pittsburgh’s second sacker had received a reduction in pay from his 1907 salary or he had not made $5,000 during the previous season. “May Lose Another Player.”

69 Bill Burgess, “Historical Salaries,” https://www.baseball-fever.com/forum/general-baseball/history-of-the-game/55494-historical-salaries (accessed on October 1, 2018); Dennis DeValeria and Jeanne Burke DeValeria, Honus Wagner: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1995), 136; William Hageman, Honus: The Life and Times of a Baseball Hero (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1996), 88; and Arthur D. Hittner, Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball’s “Flying Dutchman” (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1996), 166.

70 Baldassaro, “Ed Abbaticchio: Italian Baseball Pioneer,” 29, and Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball, 15. The quotation varies slightly between the sources, with Baldassaro, “Ed Abbaticchio: Italian Baseball Pioneer,” using an “an” before “historical” and Baldassaro, Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball, using an “a” before “historical.”

Full Name

Edward James Abbaticchio

Born

April 15, 1877 at Latrobe, PA (USA)

Died

January 6, 1957 at Fort Lauderdale, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.