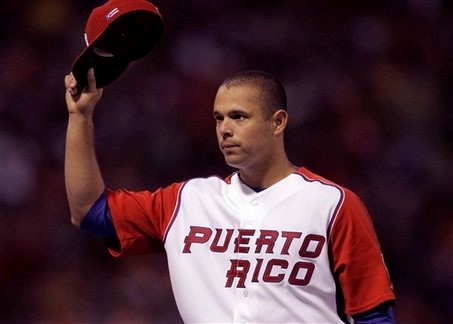

Javier Vazquez

If Javier Vazquez fought in the Civil War in a previous lifetime it was as a Confederate, because he sure had some tough times at Yankee Stadium. He was involved in three historic games in the House That Ruth Built, once as a member of the Montreal Expos and twice while wearing Yankee pinstripes. He was the victim in one of the greatest pitching performances in Bomber history, and contributed to two defeats that might have had Ruth, Gehrig, and DiMaggio spinning in their graves.

If Javier Vazquez fought in the Civil War in a previous lifetime it was as a Confederate, because he sure had some tough times at Yankee Stadium. He was involved in three historic games in the House That Ruth Built, once as a member of the Montreal Expos and twice while wearing Yankee pinstripes. He was the victim in one of the greatest pitching performances in Bomber history, and contributed to two defeats that might have had Ruth, Gehrig, and DiMaggio spinning in their graves.

Despite some disastrous games in the Bronx, Vazquez had some very good seasons plying his trade for the Expos, Yankees, Arizona Diamondbacks, Chicago White Sox, Atlanta Braves, and Florida Marlins. At the end of his 14-year major-league career, he was the all-time leader among Puerto Rican major-league pitchers in numerous categories, including starts (443), wins (165), innings pitched (2,840), and strikeouts (2,536).1 During that time he acquired the nickname the Silent Assassin, for combining a quiet demeanor with a powerful, sometimes wicked, right arm.

Javier Carlos Vazquez was born on July 25, 1976, in Ponce, Puerto Rico, the son of Carlos and Aurora Vazquez. Unlike many Latin American players, Vazquez grew up in a middle-class environment; his father worked for a Puerto Rican shipping company. His lifestyle allowed Javier to attend private schools, and to pursue sports for the passion of playing rather than as a means of escaping poverty.

That passion began at age 3, when he received a baseball glove as a birthday present. He began playing Little League at 8, and continued his development throughout his teenage years to the point where at 15 he was playing against boys two and three years older than he was.

“It was at that moment that I thought he might play in the major leagues,” said Carlos. “He trained every day and I never had to force him because he is very disciplined.”2

Vazquez played high-school baseball and basketball at Colegio Ponce, and it was while he was there that the Expos made him their fifth-round draft choice in 1994 — Puerto Rican players were included in the major-league draft beginning in 1990. He began his professional baseball career at the age of 17 by going 5-2 with a 2.53 ERA in Rookie ball with the Expos’ Gulf Coast League team, and followed that up in 1995 with a 6-6 mark and a rather elevated 5.08 ERA with the Single-A Albany (Georgia) Polecats of the South Atlantic League (SAL). The Expos had their SAL franchise in Delmarva, Maryland, in 1996, and it seemed the Northern climes agreed with Vazquez, as he went 14-3, with a 2.68 ERA and 173 strikeouts in 164⅓ innings pitched. He also pitched two innings and got the win in the league’s All-Star Game.

That record got Vazquez promoted to the West Palm Beach Expos of the Advanced-A Florida State League for 1997, where he continued improving by going 6-3, with a 2.16 ERA and 100 strikeouts in 112⅔ innings. He caught the attention of the Harrisburg Senators, Montreal’s affiliate in the Double-A Eastern League when their 10-game winner Tommy Phelps went under the knife for a torn labrum in his pitching shoulder. Montreal promoted Vazquez to Harrisburg as the Senators strove to repeat as Eastern League champs, and he showed how dominant he could be. He went 4-0 in six starts, with a 1.07 ERA and 47 strikeouts in 42 innings. He added two more victories in the playoffs as the Senators retained their title.

After that season Vazquez was among the players who participated in a winter caravan with the parent club. The bitter cold of Quebec in February was lessened somewhat when Expos manager Felipe Alou told Vazquez that he had a chance to make the team in 1998. The news came as somewhat of a surprise. “I was just kind of like, ‘Wow,’” Vazquez said.3

True to his word, Alou gave Vazquez his opportunity, and he responded. On March 24, for example, Vazquez pitched five shutout innings as the Expos defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers 6-1 to end a 14-game spring-training losing streak.

Vazquez made the roster, and the Expos embarked on the season with a starting rotation that had a combined total of 6 years and 69 days of major-league service.4 Still, it was quite the honor when Vazquez got the ball for the Opening Day assignment at Wrigley Field against the Chicago Cubs. The Cubs, no doubt motivated by the fact that it was their first game since legendary broadcaster Harry Caray died during the offseason, won 6-2. Vazquez gave up three earned runs in five innings of work.

That outing typified his season, as the overmatched 21-year-old stumbled to a 5-15 record with a 6.06 ERA. One bright spot was his first major-league victory, a 7-4 win over the expansion Arizona Diamondbacks, but it was clear he still had a way to go before he would become an effective pitcher, and he couldn’t help but be frustrated.

The 1999 season began as a repetition of 1998 for Vazquez, as hitters continued blasting his pitches to the far reaches of major-league ballparks. Giving up six earned runs in 3⅓ innings to the Diamondbacks on June 2 dropped his record to 2-4 with a 6.63 ERA, and the Expos felt he needed a change of pace in more ways than one. They demoted him to Ottawa of the Triple-A International League, where he learned how to throw a straight changeup to right-handed batters, and how to throw from the stretch.

The results weren’t immediately apparent during his first start with Montreal after he returned from Ottawa on July 18, which just happened to be the date of his first encounter with history at Yankee Stadium. His mound opponent that day was David Cone, who threw a perfect game as New York won 6-0; Vazquez gave up all six runs.

Things started to click for Vazquez after that. He pitched his first career complete game in his next start, a 5-1 win at home against Pittsburgh that began a four-game winning streak. His record finally went over the .500 mark in a 3-0 one-hit shutout at Dodger Stadium on September 14 to go 8-7. He finished the year at 9-8 with a 5.00 ERA, but after losing against the Yankees, he was 7-3 with a more respectable 3.77 ERA.

Whenever a player improves significantly in one season, the question becomes whether he can continue in the next campaign. Vazquez answered that question in his first start of 2000, giving up two earned runs in seven innings against the Dodgers at Olympic Stadium. Despite the fine performance, he received a no-decision in the Expos’ 6-5 win.

Vazquez won six of his first seven decisions, including a 2-0 win over the Diamondbacks and eventual Cy Young Award winner Randy Johnson. He went eight innings, gave up five hits, walked two, and struck out seven. The Big Unit, who was 7-0 for the season going into the game, was impressed.

“Any time you lose 2-0, the opposing pitcher pitched outstanding,” Johnson said.5

The vagaries of playing for a lousy team — the Expos lost 95 games that year — can be maddening. Vazquez gave up seven earned runs in getting his sixth win, but was the losing pitcher in consecutive 8-1 blowouts, despite giving up five earned runs over 11 innings. In August he pitched in two games the Expos lost 4-3, pitching seven scoreless innings in one and giving up two earned runs over seven innings in the other. He lost his only decision of the month 7-0 to Los Angeles, but even in that game he felt he pitched well.

“I made some good pitches, they were just hitting them,” Vazquez said. “I threw strikes and got ahead of people.”6

A few clunkers and some bad luck aside, Vazquez had another good season, going 11-9 with an improved 4.05 ERA.

Even though Vazquez didn’t miss a start in 2000, Alou took an approach with him in 2001 that was unusual for its day, but is now standard procedure. Vazquez was cruising along with a 10-0 lead after seven innings against the Mets in his second start of the season, on April 7, when Alou pulled him after seven innings.

“(A)fter he hit the 100-pitch mark, manager Felipe Alou took him out,” wrote Stephanie Myles. “Alou is insistent that even his ace be well-rested so that he can be strong in September.”7

Maybe Alou should have kept him out until then, because Vazquez had a Jekyll-and-Hyde kind of first half. He gave up six earned runs in 4⅓ innings in his next start, on April 13. After giving up eight earned runs on April 29 and five more on May 4, he went out and pitched 16 consecutive scoreless innings in his subsequent two appearances. He was consistent in June only in that he lost four straight decisions.

After his June swoon, Vazquez hid the Hyde juice and put in an All-Star-caliber performance; if they only counted games from July on, he would have won the Cy Young Award hands down. Entering the month with a 6-9 record, he went 10-2 for the rest of his season, with a 1.92 ERA and 102 strikeouts in 108 innings pitched. It was almost like a corny old movie when the pitcher who thought his girlfriend had left him finds out she really does love him.

The turnaround, according to Expos catcher Michael Barrett, occurred after the Braves roughed Vazquez up for seven earned runs in 6⅔ innings in a 10-5 loss at Olympic Stadium on July 28. “It was in the sixth inning … and he gave up like four runs,” Barrett said. “It was almost like a light switch turned on, and he just said he was better than that and he wasn’t going to give up any more runs. Then we went out and he was dominating game after game.”8

But then disaster struck. In the Expos’ first game at Olympic Stadium after the World Trade Center disaster, Marlins pitcher Ryan Dempster hit Vazquez squarely in the forehead with a fastball (the crack could be heard throughout the nearly empty Big O), causing fractures around his orbital bone and ending his season. It was typical of the Expos’ season that they scored six runs that inning to go up 6-0, but gave up eight runs the next inning and lost the game. Had Vazquez not been injured and earned the “W,” he had an outside shot at a 20-win season.

Vazquez had a better shot at being shot by Expos manager Frank Robinson in 2002. After he recovered during the winter from his season-ending injury, the inconsistency returned as he went back to his win-one-lose-one ways. In August somebody turned the switch off completely, as he lost seven straight decisions, ruining any chance the Expos had of making the postseason as they finished 83-79. Vazquez managed to win his last two decisions to bring his record up to 10-13 with a 3.91 ERA, but the season was clearly a disappointment.

Things didn’t start off much better for Vazquez in 2003, either. He wanted a raise to $7.15 million from the $4.75 million the previous year. The Expos took him to arbitration, where he lost his case and had to settle for the $6 million the Expos offered. He wasn’t just unhappy about the decision, he also didn’t like being the only Expos player whose contract wasn’t settled without going the arbitration route.

On that same day, Vazquez had to make an emotional about-face as his wife, Kamille, whom he married in 1998, went into labor. Vazquez left training camp to be with her and was there when their daughter, Kamila, was born. Despite the joy of his new family arrival, he was still angry with Expos management the next day for how they handled the situation.

“I am a person who is grateful [for receiving a $6 million salary] and I’m not saying I had an All-Star season because I didn’t,” he said. “The wins weren’t there but everything else was there. I really thought they were going to treat me better.”9

Vazquez’s mood may have improved once the season started, as his grandmother, Isabelle Arroyo, finally got to see him pitch in the major leagues and she didn’t even have to leave Puerto Rico to do it. That’s because the Expos’ owners, MLB, decided to have the Expos play 22 games at Estadia Hiram Bithorn in San Juan. Vazquez took the San Juan hill on April 14 with Grandma, his parents, and other family members looking on, and left after six innings with the score tied 3-3 — the Expos won the game, 5-3. Isabelle high-fived many people when Javier singled and drove in a run in the second inning.

Despite a brutal travel schedule, Vazquez was having a fine season and the Expos were still in the wild-card hunt when September rolled around, which is exactly when he decided to go into the tank.10 He went 1-4 for the month and finished a promising season at 13-12 with a 3.24 ERA, the lowest of his career to that point. He also set career highs in innings pitched (230⅔) and strikeouts (241, third in the National League).

That fall the Yankees and Boston Red Sox met in an epic American League Championship Series, which the Yankees won on a home run by Aaron Boone in the bottom of the 11th inning. Vazquez didn’t know it, but Boone’s triumphant circling of the bases would directly affect his career. It started on November 28, 2003, when the Red Sox obtained Curt Schilling from the Diamondbacks. The Yankees wanted to upgrade their pitching staff to counter Boston’s move, and obtained Vazquez on December 4.11 It turned out to be a season like no other in his career.

Vazquez’s first start of the season in the home opener, on April 8, almost didn’t happen as he had to show his ID to stadium security personnel before they let him in the building.12 He made a name and a face for himself after giving up one run over eight innings as the Bombers won 3-1.

After going 3-2 in April, Vazquez was Bronx Bombed in early May, giving up 12 earned runs in two starts as his record dropped to 3-4. Again he turned things around after that, winning seven of his next eight decisions. Then on July 8, Vazquez found out he was going to his first All-Star Game as a replacement for the injured Tim Hudson. He got into the game, too, pitching a 1-2-3 fifth as the American League pounded the National League, 9-4, in Houston.

His second memorable game at Yankee Stadium, was another historic occasion. The Yankees, who had an 8½-game lead over the Red Sox on July 31, had seen that lead dwindle to 4½ when Vazquez toed the rubber against Cleveland on August 31. What followed was a 22-0 Yankee loss, the most lopsided defeat in the team’s illustrious history.13 Vazquez lasted only 1⅓ innings during which he gave up six earned runs (amazingly, all 22 runs in the game were earned — at least the Yankees didn’t commit any errors) on five hits.

New York recovered from that debacle and won the American League East Division title, giving Vazquez his first trip to the playoffs. He started against Minnesota in what turned out to be the deciding game in the Division Series, giving up five earned runs in five innings with a no-decision as the Yankees won 6-5 in 11. He came on in the third inning during Game Three of the ALCS against Boston with New York in front 6-4. Despite giving up four runs in 4⅓ innings, he got his only postseason victory as the Yankees won 19-8 to go up 3-0 in the series.

But this was 2004, and the Red Sox clawed back to tie the series at three games apiece. In Game Seven, Yankees manager Joe Torre brought Vazquez in to face Johnny Damon with one out and the bases loaded in the bottom of the second. This being Vazquez’s third historic game, you can guess what happened; Damon rocketed his first pitch into the Bronx night sky as the Red Sox completed the most incredible comeback in baseball playoff history.

Vazquez was banished to the desert in January 2005 when the Yankees shipped him, two other players, and $9 million to the Diamondbacks for Randy Johnson. The All-Star season from the year before proved a memory as Vazquez once again went back and forth until he had another second-half slump, losing six of eight decisions from August 3 until the end of the season. He finished 11-15 with a 4.42 ERA. After the season he demanded a trade because he wanted to play for a team east of the Mississippi River so that his family could return to Puerto Rico during the season more easily. Arizona traded him to the Chicago White Sox for three players and cash.

“It was a really tough decision because I really enjoyed my time in Arizona,” he said. “I had a good time with the guys on the team and everyone there.”14

After a lackluster 2006 season with the Sox where he went 11-12, Vazquez had a career year in 2007, going 15-8 with a 3.74 ERA and 213 strikeouts in 216⅔ innings pitched. The difference this time was a very strong second half; beginning August 4, he went 7-2 the rest of the way. Maybe he wanted to fulfill manager Ozzie Guillen’s prophecy.

“My prediction in spring training [was that] Vazquez was going to be the most consistent guy we have, and he has been,” Guillen said.15

But that prediction didn’t carry over into 2008, where Vazquez’s second-half troubles returned when he lost six of his last eight decisions. This rough patch typified Vazquez’s inconsistency. After pitching 7⅔ innings of shutout ball in a 4-2 victory over Detroit, he gave up seven, five, and seven runs in his last three decisions, all losses, and finished 12-16 with a 4.67 ERA. Still, the White Sox made it to the postseason against the surprising Tampa Bay Rays. Vazquez started the opener but didn’t last long as the Rays pasted him for six earned runs in 4⅓ innings, giving him a lifetime playoff ERA of 10.34. At least one local scribe made note of his less-than-stellar playoff performance.

“No surgical procedure exists that would help (Vazquez) rise to the occasion in important moments, but how about an outpatient visit that at least makes him throw strikes,” wrote Rick Morrissey.16

That was enough for the White Sox, who traded Vazquez back to the National League, this time the Braves. Gone were the days of Glavine, Smoltz, and Maddux, but Atlanta still had a good pitching staff. Vazquez fit in quite nicely there in 2009, tying Derek Lowe for the team lead in victories with 15 — along with 10 losses — and a career-best 2.87 ERA, along with 238 strikeouts in 219⅓ innings. Braves manager Bobby Cox may have had a sleepless night on August 31 because he didn’t know what kind of Vazquez he was going to get in September. The 32-year-old came through, going 4-1 for the month, but that wasn’t enough to lead Atlanta to the playoffs.

With their pitching depth, the Braves felt they could part with either Lowe or Vazquez, although they preferred to part with Lowe. The interest level in Lowe wasn’t very high, so Atlanta ended up trading Vazquez back to the Yankees as part of a deal that brought them Melky Cabrera to shore up their outfield.

Vazquez’s New York revival in 2010 didn’t go as hoped because he had lost some of the velocity on his fastball. He lost four of his first five, won some, then lost some more. By August 25, Yankees manager Joe Girardi decided that rookie Ivan Nova had earned some time in the rotation, which relegated Vazquez to a relief and spot-starting role until the end of the season. He finished at 10-10 with a 5.32 ERA. His 157⅓ innings pitched were the second lowest of his career, and his mediocre performance prompted Girardi to leave him off the postseason roster.

Not surprisingly, the Yankees did not re-sign Vazquez, and that fall the Marlins inked him to a one-year deal for $7 million. At first it looked as if the Marlins got taken; he allowed seven earned runs in 3⅔ innings against the Diamondbacks on June 11 to go 3-6 with a 7.09 ERA. But then he activated the same switch that turned his 2001 season around. He went 10-5 after that with a 1.92 ERA, winning his last six decisions to finish at 13-11 in what turned out to be the last season of his career. He was the only starter with a record above .500 on a team that finished 72-90. Appropriately, Vazquez’s final start, on September 27, came against the franchise that drafted him, but was now located in Washington, and it finished in dramatic fashion. He had gone all the way as the Marlins and Nationals were tied 2-2 with two out in the bottom of the ninth. Marlins manager Jack McKeon had already decided that Vazquez would go out for the 10th, but Bryan Petersen made the decision moot as he smacked a game-winning solo shot. It was a nice way to go out.

“I’ve been blessed to be in the big leagues for 14 years. I feel it’s time,” he said after the game. “I’m glad I’m pitching well because it would be tough retiring on a bad note.”17

Although Vazquez never pitched after that, he did consider representing Puerto Rico in the 2013 World Baseball Classic, but knee surgery prevented him from participating. As of 2016 he was an international special assistant with the Major League Baseball Players’ Association, where his role was to increase the profile of the game around the world. He lived in Puerto Rico with his wife, daughter, and son Javier.

Last revised: August 1, 2018

This biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also used:

Celebritybabies.people.com.

Chicago Tribune.

harrisburgsenatorsmlb.wordpress.com..

Jockbio.com

Liebman, Ronald C. “The Most Lopsided Shutouts.” SABR Research Journal archives.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Porter, David L., ed. Latino and Latin American Athletes Today: A Biographical Dictionary, (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004).

USA Today.

Notes

1 Jordan Wevers, “MLB’s All-Time Puerto Rican-Born Team,” calltothepen.com, June 12, 2016. Translation by author.

2 Hugo Dumas, “Javier Vazquez, la Fierte de Ponce (The Pride of Ponce),” La Presse (Montreal), April 13, 2003: D1.

3 Ed Price, “Vazquez to Get Shot at Starting Rotation,” Palm Beach Post, February 24, 1998: D6.

4 “Baseball Today,” Palm Beach Post, April 4, 1998: 5C.

5 “Johnson Loses to Montreal Despite 12 Ks,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), May 17, 2000: C5.

6 Paul Gutierrez, “Dodgers Get Lift From Park,” Los Angeles Times, August 25, 2000: D9.

7 Stephanie Myles, “Barrett Might Have More Pull at the Plate and on the Mound,” The Sporting News, April 16, 2001: 30.

8 Glenn Kasses, “Vazquez Flips the Switch,” Palm Beach Post, February 28, 2002: 5C.

9 Scott Brown, “Vazquez Criticizes Expos,” Florida Today, February 20, 2003: 4D.

10 As of August 31, Montreal had a 71-67 record. The Phillies and Marlins were tied for the lead in the wild card with 73-63 marks. Between September 1 and September 12 the Expos flew from Miami to Philadelphia to San Juan to Montreal. After defeating the Cubs in San Juan on the afternoon of September 11, they flew to Montreal to continue their “homestand” on September 12 against the Mets. MLB also didn’t allow the Expos to obtain any players or call anyone up from the minors in September.

11 The Yankees sent Randy Choate, Nick Johnson, and Juan Rivera to Montreal.

12 “Cool Vazquez Wins N.Y. Debut,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), April 9, 2004”: 6D.

13 Steve Popper, “Yankees Slide to a New Low Against Indians: 22-0,” New York Times, September 1, 2004.

14 Bob McManaman, “D-backs Prepared to Move on,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), November 12, 2005: C3.

15 Dave van Dyck, “Goals Remain Despite Lost Season,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 2007: Section 3, p. 7.

16 Rick Morrissey, “That Stings: Vazquez Flops Again on Big Stage; Sox Drop Opener,” Chicago Tribune, October 3, 2008: 2A-1.

17 Joe Capozzi, “Petersen’s Home Run Gives Win to Vazquez,” Palm Beach Post, September 28, 2011: 5C.

Full Name

Javier Carlos Vazquez

Born

July 25, 1976 at Ponce, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.