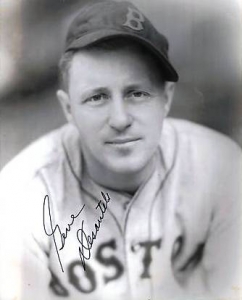

Gene Desautels

Eugene Desautels, a right-handed-batting catcher and protégé of Crusaders coach Jack Barry, jumped directly from Holy Cross College to the major leagues in 1930 without a stop in the minor leagues. He’d been a high school football star and was admitted to Holy Cross on an athletic scholarship, but his plans to play college football were scotched when the athletic department concluded that he was too valuable working behind the plate. Worcester, Massachusetts, native Desautels was fortunate to play for a couple of truly stellar teams under Barry, and he was quick to credit Barry as an important influence.

Eugene Desautels, a right-handed-batting catcher and protégé of Crusaders coach Jack Barry, jumped directly from Holy Cross College to the major leagues in 1930 without a stop in the minor leagues. He’d been a high school football star and was admitted to Holy Cross on an athletic scholarship, but his plans to play college football were scotched when the athletic department concluded that he was too valuable working behind the plate. Worcester, Massachusetts, native Desautels was fortunate to play for a couple of truly stellar teams under Barry, and he was quick to credit Barry as an important influence.

In 1929, the Crusaders reeled off 20 wins in a row. It’s not surprising that scouts flocked to watch the team. The 20th consecutive win was on June 11, 1929, and Desautels hit two triples in the game and stole a base. The Crusaders finished the year with a 28-2 record. They’d been 19-3 in 1928 and were 17-3-1 in 1930, winning the Eastern Championship each of the three seasons. When “Red” Desautels was inducted into the Holy Cross Varsity Club Hall of Fame in 1981, he was celebrated as the best catcher in Holy Cross history. His batting average increased each year, from .368 to .423 to .484. It was Detroit Tigers scout Jean Dubuc who signed Desautels.

Eugene Abraham Desautels was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, on June 13, 1907, to Victor William “Willie” Desautels and Mary “Dollie” Willette. Willie was born in Quebec and moved to the Quinebaug Village section of Dudley, Massachusetts by 1890. Dudley, a town located 18 miles south of Worcester on the Connecticut border, attracted many French-Canadians to work in its textile mills. Willie (1877-1967) worked as a laborer and later was foreman in a satinet mill (satinet is a faux satin made mostly from cotton). Dollie, also of French Canadian descent, was born in Massachusetts around 1880. She and Willie, who were married at age 16 and 19 respectively, had six children together, four boys, Ernest William (b. 1898), Alfred Loyd (b. 1900), Armand (b. 1903), Eugene and two daughters, Pearl A. (b. about 1902) and Viola L. (b. about 1912). Sadly, Dollie died at an early age, sometime between 1912 and 1918.

Gene had played baseball by the age of six. His brother Fred wanted to be a pitcher and drafted Gene to catch for him; Gene never had a chance to try another position. By age 14 he was helping out as batting practice catcher for Rockdale in the Blackstone Valley League. The team played three games a week, and during a game against East Douglas (the team featured a young Hank Greenberg at the time), a dispute arose and umpire Bill Summers tossed out Rockdale’s catcher. “You can’t do that!” yelled the manager. “All I have left is a three-dollar catcher.” The three bucks was what Gene took home. Summers said he didn’t “give a damn if he was a 10-cent catcher.” And Gene found himself in the game. Jack Barry was at the game and he liked what he saw. Gene had entered a vocational school, planning to specialize in textile dyes, but Barry talked him into going to high school and later to Holy Cross. [1]

After graduating with his bachelor of philosophy degree in June 1930, “Red” Desautels joined the Tigers and made his major-league debut in the second game of a June 22, 1930, doubleheader against the Red Sox. He was 0-for-1 at the plate, with a successful sacrifice, in a game called after six innings due to Boston’s Sunday closing law that required games to be over by 6 p.m. The Tigers took both games. Desautels collected his first hit on the 24th off Red Sox righty Hod Lisenbee. Ray Hayworth, Detroit’s main man behind the plate, played in only 77 games that year. Pinky Hargrave was the most-used reserve backstop, with 55 games, followed by Desautels who appeared in 42 games. Gene’s batting was anemic, however, just .190, with nine RBIs to his credit.

That was the story throughout his career. Except for his 1938 season with the Red Sox, Desautels was valued much more for his catching talents and work with the pitchers than for his bat.

Years later, Joe Cronin, the former Red Sox manager but by then president of the American League, was asked in testimony before the Senate Antitrust Subcommittee if he’d even seen a player win an argument with an umpire. Yes, he told the senators: “Gene Desautels, then a rookie catcher with Detroit, was a cocky young fellow and was giving umpire Cal Hubbard a hard time. On a play at second, Desautels slid in and Hubbard called him out. I think Hubbard was hoping Desautels would complain so he could throw him out of the game, too. Desautels said sweetly, ‘You can’t call me out.’ Hubbard blustered, ‘Oh, no? Why not?’ ‘Because I’m sitting on the ball.’” [2]

Come 1931, Desautels dropped down a notch and became the fourth catcher on the Tigers depth chart. Ray Hayworth remained No. 1, with the recently added Johnny Grabowski and Wally Schang sharing backup roles. Gene was seen (in the Washington Post) as “a clever youngster who is not any too effective with the stick.” Consequently, he played most of the year for Columbus of the American Association and got some work in; he hit .273 in 275 at-bats, driving in 32 runs. Gene got into three September games with the big-league club, managing just one single in 11 at-bats.

He played in Detroit for the next two years, again in a reserve role sharing duties with Muddy Ruel in 1932 with Hayworth playing a little more than half the games. Gene was with the ballclub but sat on the bench for a full 100 games before getting his first start. Desautels got the nod as second-string catcher for 1933, but his hitting held him back from seeing more work. He caught in 30 games in 1933, a couple more than Johnny Pasek. The stick work was still problematic; he hit .236 in 1932 but only .143 in 1933, and drove in but six runs in the two years combined. Though he was not used as much as he would have liked, Desautels told interviewer Brent Kelley that manager Bucky Harris “did more for me than anyone.”

When Mickey Cochrane took over as catcher-manager for the Tigers in 1934, Hayworth dropped to second string, and it was back to the American Association for Desautels. He was optioned to Toledo in early April. He spent the full year catching for the Mud Hens and fared better against American Association pitching, hitting .268. Then he headed west, sold to Hollywood on November 28, 1934. He got in a full year of work with the Hollywood Stars in 1935. Manager Frank Shellenback had quite a team, with Bobby Doerr, George Myatt, Vince DiMaggio, and more. And Gene found himself a Hollywood Star on the silver screen, too. The final scene in the 1935 motion picture Alibi Ike was shot at Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field, starring Joe E. Brown and Olivia DeHavilland, but included more than a dozen ballplayers including Desautels. In regular season action, Desautels had 426 at-bats and showed some power with six home runs, batting .265. When the Coast League franchise Stars moved to San Diego and became the Padres in 1936, Desautels really picked it up, hitting at a .319 clip in 480 at-bats over 148 games.

Eddie Collins of the Red Sox had a good relationship with owner Bill Lane of the Padres. On September 4, 1936, the Boston Red Sox purchased Desautels for 1937 delivery. Joining Gene from San Diego on the 1937 Red Sox roster was Padres second baseman Bobby Doerr. Collins kept in close touch with Desautels, who lived in San Diego the winter of 1936-37. Collins had seen Ted Williams with the Padres and was immediately impressed, getting a handshake agreement that Lane would offer him the chance to sign Williams when the time came. Desautels wrote Williams’ biographer Michael Seidel that Collins had called him and asked him to “keep tabs on Williams.” Ted asked Desautels to pitch to him throughout the winter months after the 1936 season and Gene did, “by the hour that winter … willing enough but not at the pace Williams desired.” He later advised Collins to purchase the option on Ted.

A few days before the 1937 season opened, Gene Desautels returned to Worcester and saw his Red Sox shut out the Holy Cross Crusaders, 5-0. After Rick Ferrell was traded to the Senators in June, Desautels became Boston’s first-string catcher, backed up by Moe Berg. He played in close to two-thirds of the games and batted .243. He drove in 27 runs. The Sox finished in fifth place.

Desautels moved and took up residence in Quinebaug, Connecticut. He enjoyed playing for New England’s major-league team. In 1938, with Johnny Peacock as his backup, Gene did even better, and he surprised his manager; before the 1938 season Cronin said, “We’re a little weak in catching. Gene Desautels, he’s a corking receiver, and a grand boy, but he doesn’t hit much.” Wearing number 2 now that Rick Ferrell had been traded to Washington, Gene had his best season, batting .291, driving in 48 runs and even hitting his first two major-league home runs. The first came on April 26 in Washington, an inside-the-park blast to Griffith Stadium’s deep center field off former Red Sox pitcher Pete Appleton (previously known as Pete Jablonowski), and the second was hit on May 14 off knuckleballer Dutch Leonard, also of the Washington Senators.

There was an unusual incident that occurred in either 1937 or 1938, when Desautels may have helped save Joe Cronin’s life – or Eric McNair’s! Peter Golenbock quoted a player who preferred to remain anonymous as saying that he and Desautels were sitting in the Book Cadillac Hotel and heard a noise outside their seventh- or eighth-floor window. It was Eric McNair outside on the ledge. He was “stiff as a hoot owl. And he had a gun in his hand.” He told the two ballplayers, “I’m going to kill Cronin.” It took them about 45 minutes, but they eventually talked McNair back inside. “That ledge wasn’t very wide,” Desautels told Golenbock, “and we were afraid he might fall off and kill himself, because he had been drinking. If he had slipped, he would have been dead.” [3]

Desautels was never a star backstop. The Red Sox simply lacked great catchers in these days. Entering 1939, Harry Ferguson of United Press offered the assessment that “Gene Desautels and John Peacock make up an adequate but not brilliant catching staff.” The left-handed-hitting Peacock pushed his way into a platoon situation, garnering 274 at-bats compared to Gene’s 226. Peacock hit .277 and Desautels .243, matching his 1937 mark and distinctly down from the .291 he’d hit in ’38. Gene started the season dismally, hitting well under .200 for the first couple of months, but was considered a solid defensive catcher in whom the pitchers had confidence.

A July 2 game against the Yankees showed some of his grit. In the first inning of the day’s doubleheader, Tommy Henrich collided at home plate and knocked Gene cold – but he held onto the ball and Henrich was out.

Jack Malaney of the Boston Post paid Gene a real tribute in the August 17, 1939, Sporting News, noting that “Gene Desautels caught all of the 12 victories Lefty Grove had pitched without ever once shaking off his catcher.” Gene came up with a “lame arm” in mid-August, though, and had to take a few days off for treatment.

Looking back on Red’s tenure with the team over his first three seasons, owner Tom Yawkey nodded in his direction while sitting in the stands in Sarasota in March 1940 and said, “There’s a man who does not get the credit that belongs to him. Gene may not hit as hard as some other catchers you could name, but for my money there is nothing wrong with his catching. He is one of those steady workmen who does everything easily and gracefully, with the result that not too much attention is paid him.” [4] Joe Cronin agreed, calling Gene “the most underrated catcher in the American League.” Desautels worked hard, too, and worked “as hard and as faithfully as if he were a rookie trying to earn a job,” the newspaper said.

Desautels caught one more year for the Red Sox, in 1940, with both he and Johnny Peacock beating back a challenge for the catcher’s slot from George Lacy of Minneapolis; Gene played more than Peacock but still fell short on offense, declining further at bat, hitting just .225. Cronin was never fully satisfied with either. SABR’s Mark Armour notes that the role of catcher had become such a sinkhole for the team that Jimmie Foxx volunteered to catch to allow Lou Finney the chance to play first base. Foxx was the regular catcher for six weeks or so, and appeared in 42 games behind the plate. After the 1940 season, the Sox helped engineer a three-team trade in December that saw Desautels, Jim Bagby, and Gee Walker go to the Indians, while catcher Frankie Pytlak, Odell Hale and Joe Dobson came to Boston. The Red Sox had shipped Doc Cramer to the Washington Senators, acquiring Walker so they could package him in the deal. The Indians felt that Gene would be “every bit as good as Pytlak” as their second-string catcher. Desautels declared, “Thank goodness I won’t have to face that Bob Feller again.” He thought it was a good trade for Cleveland. Jim Bagby, in a subtle slap at Joe Cronin, said he thought that playing “under different management” would benefit him. “I didn’t pitch my own game in Boston,” he said.

The Washington Post‘s Shirley Povich found the trade fascinating, but didn’t think the Red Sox improved themselves any. It was Walker who was the key to the deal for the Indians, he wrote. “Desautels and Bagby scarcely figure to bolster the Cleveland club. … .Desautels is a nice sort of lad, but he has been the chief reason why the Boston catching staff was never rated highly and why, finally, Jimmy Foxx was called behind the bat last season. The Indians will hardly use Desautels much.” The Indians had Rollie Hemsley as their first-string catcher but he was showing signs of self-limitation, both in terms of age and alcohol. In early January, the Tribe picked up George Susce as a backup, but Desautels got into 66 ballgames and was kept busy. He was a hard worker who generally got good marks for his catching, but really struggled with his hitting. To his credit, he kept trying. Arch Ward led a March 1941 column in the Chicago Tribune by noting that, despite 12 years in baseball, he “still asks other players to help him improve his hitting.”

It wasn’t long before Desautels began to make a good impression on the field. Bill Cunningham wrote a May 21 column in the Washington Post praising Hemsley (“one of the most notorious bottlemen in all baseball”) for his success with sobriety, and added, “Desautels … seems ideal as Hemsley’s understudy and Cleveland is delighted with him.” There were very few outstanding games, though. On July 5, he was 2-for-4 and drove in two. He had his third and last big league home run on May 14 at Yankee Stadium off future Hall of Famer Red Ruffing. By year’s end, though, Gene had pretty much matched his 1940 totals – 17 RBIs but a lower average, just .201. There was one embarrassing moment for him on July 26, at Fenway Park, when he looked to have singled to right field but Lou Finney played the ball so quickly that he threw out Gene before he reached first base.

After the season, Cincinnati purchased Hemsley from Cleveland. The Indians planned to count on prospect Otto Denning, with Desautels as a backup. Shirley Povich wrote that the Indians could carry Desautels “because he is a good catcher.” He improved his average considerably in 1942, but didn’t get nearly as much work as had been planned due to a fractured fibula – a broken leg – suffered in a collision while blocking the plate against Detroit’s Billy Hitchcock on May 10. He was expected to be out about six weeks, and the Indians called up Jim Hegan. It was nearly 10 weeks, though, before Desautels returned, catching two innings of a game and singling. Hegan replaced him as a runner and saw the game through to the 12th inning, when Hegan singled in the winning run. In the first game of two on August 11, Gene set a major league record for the longest game played in which a catcher had neither a putout nor an assist – a 14-inning game that ended in a 0-0 tie. Al Milnar had a no-hitter through 8 2/3 innings until Roger Cramer broke up his bid – but he didn’t strike out even one batter all game long. In December, the Indians acquired Buddy Rosar from the Yankees, presumably to make him the first string catcher. However, manager Lou Boudreau claimed in April 1943 that Rosar would be backing up Desautels. Denning had become a first baseman, and Hegan had entered the Coast Guard. In fact, Rosar earned his way and played most of the games, hitting .283 while Desautels finished the season with his usual 60-some games, this year batting just .205.

At the end of the season, Desautels was ordered to report for induction into the United States Army on January 5, 1944. Gene and his wife, Josephine Connolly of Detroit, had two children at the time (a third was born later), and he was working in the offseason at the Heywood-Schuster Shoe Company in Douglas, Massachusetts, but there was a war on. He was living in Dudley, near Douglas, at the time. When due to report, he received a deferment for a month, but made a move of his own and enlisted in the Marines on February 29. He reported to the Parris Island training center in South Carolina – and by August was reported the leading hitter on the Parris Island baseball team. During the winter months, PFC Desautels was named basketball coach of the Parris Island Marines team. He managed the baseball team for two summers – his first time as a manager.

Desautels was discharged from the Marines on July 28, 1945, and was clearly in the best of shape; he was back in the game for the Indians just a week later, playing the second game of their August 5 doubleheader. He didn’t play much the rest of the season, though, getting in just nine at-bats and only one hit. In mid-September, not even waiting until season’s end, the Indians placed him on waivers and he was claimed by the Philadelphia Athletics on September 17.

Athletics manager Connie Mack, slated Buddy Rosar, who had been traded from Cleveland before Desautels, as Philadelphia’s top catcher, with Jim Pruett (who’d hit .303 with Toronto in 1945) as second. Gene was third. On March 29, though, the situation brightened as Mack sold Pruett to the Giants and said he’d go with just Rosar and Desautels. This proved to be the case, though the team results weren’t at all favorable – the Athletics finished last, 55 games behind the Red Sox. Gene hit .215 in his last season of major-league ball, driving in 13 more runs. One of them was a nice one to remember in the years ahead – a bases-loaded single he hit in the bottom of the ninth to win a 1-0 game in Philadelphia on August 29 against the Indians. He was given his unconditional release by the Athletics during the offseason.

Desautels had performed one last service as a major leaguer, though. He was Philadelphia’s “player rep” to a meeting held in Chicago on July 29, 1946. The players recommended the implementation of a pension plan, a minimum salary, provisions for players to receive a percentage of money during a waiver deal or trade, a provision for spring training per diems payments, and a grievance committee – all in all, an early step on the road to collective bargaining between an organized players’ group and owners.

Desautels caught for the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1947, but could only hit .188 against International League pitching, in 208 at-bats. He did hit five home runs, but it was not a good showing. That was his last year as a player, though he assigned himself 50 times at bat in 16 games while manager of the Class A Williamsport Tigers of the Eastern League. He was appointed Williamsport’s manager in December 1947 and served for the 1948 and 1949 seasons. At the end of 1949, Gene swapped positions with Jack Tighe, who’d managed the Class A Flint, Michigan, Tigers farm club – Tighe taking over Williamsport and Desautels taking over Flint. The area appealed to him and he made Flint his residence until his death in 1994, even though he managed the Flint ballclub just the 1950 season. In December, he was named manager of the Double A Little Rock Travelers and worked in Arkansas for one season, 1951, leading the team to its first Southern Association pennant in nine years.

He moved on to manage the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association in 1952, at the request of Indians GM Hank Greenberg. It was not a good season for Indianapolis, which finished sixth and drew poorly. Gene put himself in one game. Gene was named to his fifth club in five years, when hired on November 1 to skipper the Sacramento Solons in the Pacific Coast League for 1953. It had been a last-place team under Joe Gordon, who became a scout for the Tigers, and Gene’s first year saw the team destined to go nowhere. The team surprised at first, starting off hustling, though losing several one-run games. In the end, the Solons sank to the bottom once more. Gene did his part for the team, taking part in egg-throwing contests before a game or two, and getting into it a couple of times with umpires, but the staff had two 17-game losers and – as predicted – finished last. Discouragingly, there were few moves made to try to improve the club over the winter. Again, the 1954 team started off better than expected, and this time did well for the first month or so, but then had dropped to seventh place by July, prompting Gene to resign on July 12, 1954. One of the reasons was likely the lack of support; the July 28 Sporting News referred to the Solons as “suffering from a shortage of operating capital, leading some observers to believe a change in ownership might take place there before next year.” The way Gene put it to Brent Kelley: “They were operating on a shoestring. They couldn’t afford to buy anybody or get anybody, and that was it for managing.”

Desautels got himself a position as athletic consultant working with the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation in Flint. The Holy Cross graduate used his position with the Mott Foundation to urge players to broaden themselves as individuals. “Too many players … depend too much on baseball,” he said. “So many never reach the majors and these are the ones who are not ready to meet the challenge when they reach the 35-year mark. During the last few years that I managed I urged all young players to prepare themselves for the day they were through with baseball, so they wouldn’t have to start from scratch when they reach the end of the road as active players. Many count on getting some kind of baseball job as coach, scout, or manager. However, these jobs are limited and the game is unable to care for everyone who reaches the inevitable age of ‘too old to play.’ “

The National Amateur Baseball Federation named Desautels as one of its three vice presidents. He hosted an annual tournament in Flint for several years in the late 1950s. In 1956, he invited the Red Sox’ Ted Williams and Jimmy Piersall, and the Tigers’ Charlie Maxwell to compete in a June 18 hitting contest as a benefit for the boys baseball program in Flint; Williams hit 25 drives out of Atwood Stadium.

He also helped do some scouting for the Tigers, running an area tryout camp in 1958. Gene was married early in his career but was a widower when he met Mildred Kramer, who became his second wife in 1960. He was working as school counselor at Southwestern High School in Flint, a position he held until retirement. She was a former legal secretary, retired by the time they met and, at the time of our interview, 104 years old.

Gene and Mildred enjoyed taking what they called “gypsy trips.” Mildred said they’d “just start out and go. Put the golf clubs in the back seat, and swimming suits, and away we’d go. We’d start out, nothing in mind, and just go. Especially in Canada. We liked to go across Canada. We had no time to get back. If we liked a place, we’d stay and if we didn’t, we’d move on.”

They enjoyed a number of cruises, to Scandinavia, to Japan, to Hawaii. Gene’s widow didn’t think he had a favorite team, but there was one thing he’d had enough of in baseball and that was travel by rail. “He liked the fellows he played with at each place. He got tired of riding trains, though. We went someplace and I decided we’d take the train across Canada into California. He put his foot down to that. He said, ‘I’ve had enough of that train ride in baseball.’ They practically lived on trains. That’s how they traveled. It was too much togetherness. That’s the one time he vetoed what I’d had planned.”

None of his children showed interest in baseball, nor had his first wife. Gene Junior became a health-care provider and works as a surgeon in Chico, California. His daughters, Joanne and Diane, both lived in California as well.

Gene Desautels died on November 5, 1994, in Flint. He was 87 and had enjoyed a good and productive long life. “He died of a heart attack while he was shopping at the city market,” his widow explained. “He was paying for something – buying, I think, a cauliflower – and he just dropped over. That was it.”

Sources

Interview with Mildred Desautels on May 26, 2007.

Drohan, John. “Desautels Rates High With Cronin” Unidentified article found in the Desautels player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. May 17, 1940.

Farrrington, Dick. “Desautels Began Catching at 12 for Brother; Ump’s Thumb Gave Him Semi-Pro Chance,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1938.

Golenbock, Peter. Red Sox Nation. (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2005)

Kelley, Brent. “Gene Desautels”, Sports Collectors Digest, January 25, 1991.

Unidentified article by McAuley found in the Desautels player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. February 23, 1941.

Thanks to Rod Nelson, Dick Daly, Francis Kinlaw, and James Wrobel / Holy Cross.

[1] McAuley, “So the Three-Dollar Catcher Went to College”, an unidentified article signed with just a surname, dated February 23, 1941, found in the Desautels player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Dick Farrington in The Sporting News says that Desautels was on the East Douglas team.

[2] Washington Post, February 19, 1964

[3] Golenbock, Peter, Red Sox Nation, pp. 99-100

[4] The Sporting News, April 4, 1940

Full Name

Eugene Abraham Desautels

Born

June 13, 1907 at Worcester, MA (USA)

Died

November 5, 1994 at Flint, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.