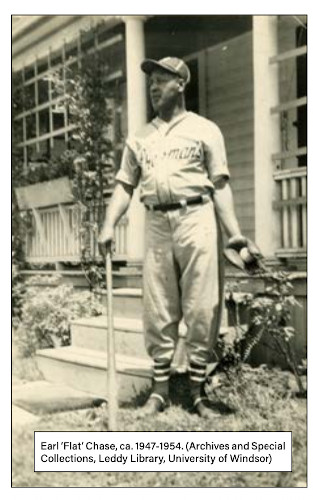

Earl Chase

Earl “Flat” Chase, ca. 1947-1954. (Archives and Special Collections, Leddy Library, University of Windsor)

Earl “Flat” Chase (1913 – 1954) was skilled as a batter, pitcher, catcher, and any field position he was asked to play. Chase was nicknamed Flat for his running style, and his skills on the field and charismatic athleticism earned him a reputation as one of the most exciting players to watch in Southwestern Ontario in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. He is perhaps best known for outpitching Phil Marchildon in the 1934 Ontario Baseball Amateur Association championship series and thus helping his team, the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, defeat Penetanguishene. The Chatham Coloured All-Stars were the first Black team to win this provincial series.

Chase was born on August 16, 1913, in North Buxton, Ontario, a community founded in 1849 by and for Black settlers, many of whom were former slaves. Chase was one of nine children born to George Chase, a laborer, and Elva Gambril. His siblings were Arthur, Viola, Lloyd, Harold, Edith, Richard, Ileen, and Ione. Early in his life, Earl moved with his family to Windsor, Ontario, across the river from Detroit. The Chases lived in the McDougall Street corridor, the center of Windsor’s traditional Black neighborhood and business district. The Chases’ house was on Mercer Street, which was the eastern edge of Wigle Park, the geographic and social heart of the McDougall Street corridor. The park offered a range of social and recreational facilities, including a baseball diamond.

Chase spent most of his days playing baseball, honing his skills, watching and then competing against the many teams that visited from the Windsor-Essex and Chatham-Kent regions, as well as from Detroit. Chase’s eldest son, Earl Jr., reflected that his father “grew up in the park across the street.”1 The McDougall Street corridor was less than five miles from downtown Detroit, and the Windsor newspapers of the 1930s document a steady flow of regional Black baseball teams into Wigle Park.2 These teams included the Saginaw Michigan Colored Baseballers (1930), the Ecorse Colored Giants (1930 and 1936), the Hamtramck Colored Stars (1931), the Philadelphia Colored Giants (1931), the Wolverine Colored Stars (1933), Quinn’s Colored Stars of Detroit (1935 and 1939), and the Detroit Colored Stars (1936), among others. It has proved difficult to locate formal documentation about these teams, but it is highly probable that they were not part of formal leagues, but rather informally organized pickup teams with crossover players playing exhibition games against teams around the area.3

Around the age of 15, Chase started playing for church league teams in both Windsor and Detroit. While there appears to be no extant record of these games, it is safe to assume that in playing for church teams in Detroit, Chase was regularly playing with and against a wide range of Black baseball players, some of whom likely played on more formalized Negro Leagues teams in and around Detroit. It is also likely that playing with and against such teams in Detroit helped push the young Chase’s innate skills to the next level.

In 1933 the Windsor newspapers document Chase playing for the Windsor Stars, along with another future Chatham Coloured All-Star, Ferguson Jenkins Sr.4 It may have been through playing for the Stars at Wigle Park that Chase and Jenkins got to know Wilfred “Boomer” Harding and his brother Len Harding from Chatham.5 It’s not surprising that in 1933, when the All-Stars were looking for talent to round out their team for the Chatham City League playoffs, they sought out Chase.

A story in the August 24, 1933, Chatham Daily News describes how “Chase[,] a hurler from Windsor who has been working in the Riverside league,” had signed on to play with the All-Stars.6 The All-Stars would go on to win the Chatham City League’s Wanless Trophy that year, and Chase’s contributions on the mound were a large part of the team’s success. Describing the final game of the series, the Chatham Daily News writes, “It was simply a case of too much Chase, who worked on the mound in both games.”7 Chase would stay in Chatham for the rest of his life, playing for a number of teams in and around Chatham.

The All-Stars’ home field, Stirling Park, was not unlike Wigle Park in that it was located in the heart of Chatham’s predominantly Black neighborhood. Like the McDougall Street area, the East End has a long-standing tradition of baseball. Most of the Black teams prior to the 1930s were informal teams like the Chatham Giants from the 1920s, who played some league games but also pickup and exhibition games at church homecomings and other weekend events. In 1932 a group of young players from the East End formed a team that, with the assistance of Archie Stirling, a neighborhood business owner and local baseball advocate, would be formally recognized in 1933 as the Stars and later be known as the Chatham Coloured All-Stars. Most of the players grew up in the East End and lived within a few blocks of the ball diamond, and hundreds of residents would turn out to watch baseball on summer evenings and weekends.

The crowd who showed up for the All-Stars’ season opener on May 17, 1934, would have seen that Chase’s 1933 playoff performance was not a fluke but rather indicative of the career he would have in Chatham. Playing second base for the first four innings and then pitching the final three innings, Chase is listed in the box score as getting one run and one hit. In the second inning, Chase turned a 4-3 double play, “nipping what appeared to be a start of a rally in the bud.”8 Of his pitching, Chatham Daily News sportswriter Jack Calder commented, “Chase went to the mound in the last three frames and effectively checked any intentions the Duns might have had to fatten their batting averages by allowing only one hit.”9 This one article hints at why Chase would go on to become a Chatham legend: He was a formidable pitcher, fielder, and hitter.

As the 1934 season progressed, Chase showed Chatham fans just what kind of a powerhouse he would become, and the local newspaper recounted the details of his on-field skills. On June 12, Calder wrote:

“With Chase hurling three-hit ball over the abbreviated route, the Stars took advantage of seven errors made by the opposition and seven hits allowed by Belanger to win going away. Chase himself led in the hitting attack with two doubles and a single in four times at bat, while his battery mate, Washington, accounted for two of his team’s other hits. Belanger and Depew worked on the mound for the Braggs and turned in good games but the free-swinging bats of Chase and Washington led to their defeat.”10

In this game and the game on June 20, Chases contributions were as both an intimidating pitcher and a strong batter: “Chase worked the entire game [against] the Duns and allowed only seven hits while striking out ten. Wright and Thompson opposed him, the former being chased after two and two-thirds innings. Boomer Harding and Chase each accounted for three of the Stars’ safe blows.”11 It is difficult to ascertain precisely how many games Chase’s pitching won for the All-Stars since stats for ERA, wins, saves, and losses were not recorded. One thing that is certain, however, is that much of the success of the 1934 team was reliant upon Chase’s ability to pitch hard throughout the games, his unstoppable bat, and his competitive spirit.

Throughout the 1934 season, Chase would be described in phrases such as the “smoke-ball artist of the Chatham Nine”12 and “the speed ball demon.”13 By September of 1934, Jack Calder of the Chatham Daily News would call Chase the “mainstay of the All-Stars’ pitching staff” and “one of the hardest hitters in amateur ball.”14 Teammate Boomer Harding commented on Chase at the plate. He

“… could hit a ball low and he could hit it high … there’s no weak spot. He could hit the ball where it was pitched. If they thought, well, we’ll pitch him outside, he’d hit it hard, he’d hit it out of the park, in left field just as easy as in Stirling which was small. But he’d still hit it further out of the park than a right hand batter would hit it out. So he was strong in any field and he’d hit it like it was pitched.”15

Chase not only awed spectators with his skills, he was also entertaining to watch as this notice in the Chatham Daily News reveals: “Flat Chase does something of a rumba every time he goes to bat, not quite the same as Dick Porter’s classical toe dance. Chase’s little act should have been set to the music of Ferde Grofé’s ‘Grand Canyon Suite.’ It’s good but there’s something weird about it. But how Chase can leather that apple. He is the hardest hitter in amateur baseball in this part of the province. That’s covering some territory.”16 For the rest of his life and beyond, his skills as a player would be talked about with superlatives and awe.

On the field, the All-Stars were challenged by some strong opponents, and they became known for fast, exciting, and occasionally aggressive play. Boomer Harding’s son Blake offered this description of the team: “And when it got nasty, they were just as nasty and aggressive and tough as anybody else out there. And if you wanted to play to hurt one of them … they gave what they got.”17 Off the field, the team also met challenges. The farther the team got from Chatham, the more they encountered hostile crowds and difficulties finding restaurants and hotels that would serve and house them. In the 1934 final series in and against Penetanguishene, the team could not find accommodations in town and had to stay in a neighboring town. In Canada discrimination based on race was not as fully codified as it was in the United States, but it was still deeply pervasive.

Sometimes the All-Stars’ athleticism, skill, and exciting style of play would win over hostile crowds. Other times having a Black team beat the local team led to events that the players remembered in vivid detail for the rest of their lives. In 1980 Kingsley Terrell, longtime teammate of Chase, recalled how

“… there was never a place that we played baseball that we couldn’t go back and play again, except one place and that was in West Lorne. We beat West Lorne and they run us out, they run us out of the town. They had clubs, and hoes, and rakes, and everything else. We got everything all packed up before the game was over because we knew there was something going to happen anyways. So, we just got the game over. When that last man was out we all got in the cars and took off and we never went back. And we couldn’t go back to play ball there no more.”18

In 1984 fellow All-Star Ross Talbot shared his memories of West Lorne: “One time in West Lorne we caused a small riot. … Boomer was going home and knocked down their catcher and people snatched boards off the fence, but we came out of that all right.”19 “As for heckling,” Talbot reflected, “we just had to take it. … At that time we had to live with it.”20 In the same interview Talbot recalled playing in Strathroy: “They wrote on the sidewalks, ‘the n___s are coming’ and the ‘black clouds are moving in,’” Talbot said, a tear coming to his eye.21 “That was the worst thing we ever came across.” An interview with Ferguson Jenkins Sr. suggests that Chase specifically was targeted in some of the things written and drawn on the sidewalks.22 In their interviews with the Breaking the Colour Barrier project,23 however, Earl Chase Jr. and Horace Chase said their father never really talked about those memories. Instead, they said, his love for the game always won out over whatever threats or hostilities he encountered.24

Chase, Boomer and Len Harding, Guoy Ladd, and Kingsley Terrell formed a core group of players who stayed with the Chatham Coloured All-Stars until they disbanded in 1939. Chatham fielded a competitive team for the remainder of the 1930s but they never won another OBAA championship. The All-Stars made it to the OBAA finals in 1939 but withdrew when conflicts regarding payment of expenses and location of the final games could not be resolved. Although the print record is vague about these controversies, oral histories have suggested there were racial undertones to the unfair travel expectations put on the All-Stars, and the lack of proper compensation for expenses. When the 1940 baseball season began, World War II was underway and several All-Stars had enlisted to serve.

Chase remained in Chatham during the war. By this time, he and his wife, Julia (Black) Chase, whom he married in November 1934, had four children, Earl Jr., Horace, Marilyn, and Gladys. Chase worked for the City of Chatham’s sanitation department and eventually was hired in a supervisory role. Work and family were a priority for Chase, but so was baseball. As Horace Chase recalled, “most of the time my dad actually played ball, tell you the truth. His love of the game was phenomenal because that was his sport. In fact, when all four of us children was born he wasn’t there for the birth, he was playing ball. That’s how much he played.”25

The Chases were a baseball family, Horace commented: “We weren’t what you’d call a much outside baseball family. We liked our baseball.”26 Chase “didn’t get into soccer or hockey, golf or any of those things. I think because my dad was used to working, and times were tough. And like I say, having four young kids with mouths to feed. I think that was his only thing, was to play ball. Live to play ball, eat, sleep, and enjoy life.”27 The centrality of baseball is a recurrent theme in Chase’s sons’ descriptions of their father’s life.

As was the case when he lived in Windsor, Chase played baseball for a range of community and regional teams, playing whenever and wherever he could. In 1938 and 1939 Chase appears to have played with the London Majors, a predominantly White team in the Intercounty Baseball League, as well as with the Chatham Coloured All-Stars. In 1944 Chase was a key part of the London Majors’ winning the Canadian Sandlot Congress Championship. In 1943-1945, there are records of Chase playing for the Chatham Arcades, who won the OBA Intermediate Championship in 1944. In 1946 a number of former All-Stars reunited to play for the Taylor A-Cs. There were enough All-Stars on the team that the Chatham Daily News‘s sports page had a headline that said, “Chatham Coloured Stars Return Under New Name.”28

From 1947 until his death in 1954, he also played with the Chatham Shermans and Chatham Hadleys. Very little formal documentation from those leagues exists today but the Chase family scrapbook documents his career, with notes and mostly undated clippings. In the scrapbook, it suggests that Chases batting average ranged from .447 while playing for the Shermans in 1947 to .525 in the City League to .786 partway through an Industrial Baseball League season. My own calculations for all the games Chase played in 1934 have him batting .488 in 127 at-bats.29 No statistics were kept for his pitching.

In the absence of official statistics, much of what we know of Chase comes from newspapers and oral histories. One of the recurrent stories of Chase is that over the course of his career he would hold the record for hitting the longest home-run balls in Sarnia, Strathroy, Aylmer, Welland, Milton, and Chatham. Whether these are official records or not, those who saw Chase play are unwavering in their description of him as a fierce competitor. All-Stars scorekeeper Orville Wright commented, “Flat hit one in Chatham I don’t think they’ve found yet. It cleared the center field fence at Stirling Park, [it] went over the trees and a house on Park Street, cleared the road and the houses on the other side and landed in a back yard on Wellington Street.”30 In 1980, King Terrell described Chase’s skills in this way:

“He could run. He was a power hitter. He could hit home runs just about as easy as the rest of us could hit singles and doubles and triples. Because at Stirling Park it didn’t seem like it took him very much of a swing to get a double over [by] the right field fence, or a home run over the center field fence. He was a spray-hitter. That means that you can hit a ball in any park over the field.

Nine times out of ten if he hit a ball south, the ball would be going direct over right field because he was a power hitter. A spray-hitter means that you can spray a ball in the outfield. Because that’s when you don’t know where it’s going to go. He was one of those kinds of guys: you didn’t know where the ball was going to go. It’s the same as his pitching. Because lots of times, Donise would ask him for a fast ball and he’s liable to throw him a curve. And ask him for a curve and he’s liable to throw you a fast ball, which I know all about – his fast balls and his curves – because he darn near killed three of us in one night.”31

Virtually every retrospective of the All-Stars’ 1934 victory features commentary like that about the legend of Flat Chase.

With all the talk about Chase’s undeniable talent, the question is always whether he could have played major-league baseball. While we will never know if Chase thought he could have played in the major leagues, everyone who saw him play was convinced he could have had there not been a color barrier. Teammate Don Washington told the Chatham Daily News that “Chase should have been a big league pitcher”32 and King Terrell told an interviewer, “Flat Chase, he could’ve been in the big leagues. There was not a better second baseman around than he was. And he was a good pitcher. God-all knows that there was nobody around in the country that could hit a ball any better or any further than he could.”33 Archie Stirling – frequently referred to as Chatham’s Mr. Baseball – wrote in 1960: “Today if Flat Chase were as good as he was when he first came to Chatham, the Detroit team would pay him thirty thousand dollars to sign with them.”34 Whether Chase could have made it to the big leagues is, of course, conjecture. Nevertheless, it is imperative that we consider the impact of the color barrier on the careers, lives, and legacies of players like Earl “Flat” Chase, and on the ways in which Canadian baseball history is written.

Notes

1 “Interview With Earl Chase Jr. and Shyla Chase,” Breaking the Colour Barrier: Wilfred “Boomer” Harding & the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, http://cdigs.uwindsor.ca/BreakingColourBarrier/items/show/722; “Interview with Horace Chase,” Breaking the Colour Barrier: Wilfred “Boomer” Harding & the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, http://cdigs.uwindsor.ca/BreakingColourBarrier/items/show/725.

2 I am grateful for Linda Bunn’s research assistance in locating these notices in the Windsor-Essex County newspapers.

3 The mention of these teams in the Windsor papers might help further what is known about the rich and active Black baseball tradition in the Detroit area in the 1930s, and offer new avenues of inquiry into the ways in which the influence of Negro League baseball may have moved into Canada.

4 Ferguson Jenkins Sr.’s son is Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins Jr.

5 Box scores from the Windsor newspapers show the Hardings and other Chatham players competing at Wigle Park against each other.

6 “R.G. Funs and Stars Will Open Championship Series,” Chatham Daily News, August 24, 1933: 13.

7 “Stars Win Wanless Trophy in Two Straight Games,” Chatham Daily News, October 10, 1933: 8.

8 Jack Calder, “1934 Inaugural Indicates Real Battle for Honors,” Chatham Daily News, May 18, 1934: 11.

9 Calder, “1934 Inaugural Indicates Real Battle for Honors.”

10 Jack Calder, “Braggs Defeated in City Baseball Games Last Night,” Chatham Daily News, June 12, 1934: 11.

11 Jack Calder, “Duns Defeated in a Hard Fought Game Last Evening,” Chatham Daily News, June 21, 1934, section 2: 5.

12 Jack Calder, “Chase to Be on Hill for Chathamites,” Chatham Daily News, July 20, 1934: 11.

13 Jack Calder, “Sarnia Red Sox Beaten at Home in OBAA Contest,” Chatham Daily News, September 10, 1934: 8.

14 Jack Calder, “Stars Begin OBAA Playdowns Thursday,” Chatham Daily News, September 5, 1934: 11.

15 Dan Kelly, “Interview with Wilfred Boomer Harding,” Breaking the Colour Barrier: Wilfred “Boomer” Harding & the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, http://cdigs.uwindsor.ca/BreakingColourBarrier/items/show/719. Accessed July 15, 2021.

16 Jack Calder, “Stars Will Draw Them,” Chatham Daily News, September 12, 1934: 11.

17 “Interview With Blake and Pat Harding (Part 1),” Breaking the Colour Barrier: Wilfred “Boomer” Harding & the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, http://cdigs.uwindsor.ca/BreakingColourBarrier/items/show/716.

18 Interview with Kingsley Terrell by Wanda Milburn, Multicultural History Society of Ontario, August 6, 1980.

19 Bill Reddick, “From the Bullpen: Chatham Colored All-Stars,” Chatham Daily News, October 4, 1984: 9.

20 Reddick.

21 Reddick.

22 Interview with Ferguson Jenkins Sr. by Vivian Chavez and Wanda Milburn, Multicultural History Society of Ontario, October 3, 1980.

23 Breaking the Colour Barrier: Wilfred “Boomer” Harding & the Chatham Coloured All-Stars is a website that tells the story of the Chatham Coloured All-Stars. It features oral histories with players’ families, newspaper clippings from the 1934 season, player biographies, and curricular resources for K-12 teachers. Breaking the Colour Barrier is a partnership between the Harding family, the University of Windsor’s Department of History, the Leddy Library’s Centre for Digital Scholarship, and the Chatham Sports Hall of Fame. It was generously funded by an Ontario Trillium Foundation grant in 2016-2017.

24 “Interview with Earl Chase Jr. and Shyla Chase.”

25 “Interview With Horace Chase,” Breaking the Colour Barrier: Wilfred “Boomer” Harding & the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, http://cdigs.uwindsor.ca/BreakingColourBarrier/items/show/725.

26 “Interview with Horace Chase.”

27 “Interview with Horace Chase.”

28 Doug Scurr, Chatham Daily News, June 12, 1946, np.

29 Elsewhere, Chase’s average has been listed as .525 for 1934 but the source for this figure isn’t clear. My calculations are based on every game for which I could find a box score in 1934, including exhibition games, various league games, and playoff games.

30 “Chatham’s First Champs Played the Game for Fun,” London Free Press, October 20, 1967, np.

31 Interview with Kingsley Terrell.

32 Bill Reddick, “’34 Champions Denied Opportunity in Pro Ball,” Chatham Daily News, October 10, 1984: 9.

33 Interview with Kingsley Terrell.

34 Archie Stirling, “A Brief History of Baseball,” in “Official Program: Chatham’s Victoria Day (1960), Breaking the Colour Barrier: Wilfred “Boomer” Harding & the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, http://cdigs.uwindsor.ca/BreakingColourBarrier/items/show/957.

Full Name

Earl Chase

Born

August 16, 1910 at North Buxton, Ontario (Canada)

Died

May 5, 1954 at Windsor, Ontario (Canada)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.