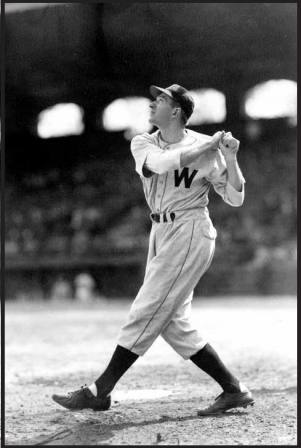

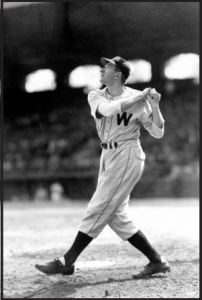

Ed Butka

The plight of the World War II-era (replacement) player included questioning stares and unflattering comments from fans wondering why seemingly healthy specimens were wearing flannel instead of khaki. The jaundiced looks were especially tough on a strapping 6-foot-3, 193-pound first baseman from Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, named Ed Butka. Despite numerous trips to his local induction center, big Ed was always turned away as unfit for military service.

The plight of the World War II-era (replacement) player included questioning stares and unflattering comments from fans wondering why seemingly healthy specimens were wearing flannel instead of khaki. The jaundiced looks were especially tough on a strapping 6-foot-3, 193-pound first baseman from Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, named Ed Butka. Despite numerous trips to his local induction center, big Ed was always turned away as unfit for military service.

Julius and Lena Tumicki Butka immigrated to the United States from Poland and settled in the growing town of Canonsburg, southwest of Pittsburgh, where Julius found work as a laborer in a tin mill. Edward Luke Butka was born on January 7, 1916; the family unit ultimately consisted of six boys and one girl. Young Ed went from playing sandlot ball in Canonsburg to working (and playing) for Home Furniture, later the Polish Falcons and finally the local Elks Club, where his power hitting earned him the nickname Babe. His ability on the diamond caught the eye of former major-league star Joe Tinker, a scout who brought the talented youngster to the attention of the Washington Senators.

In the spring of 1940, Nats owner Clark Griffith personally scouted Ed during a trip to Florida. Amateur baseball veteran Hymie Newman was on the mound as Griffith intently watched the right-handed-hitting Butka during a batting-practice session. Newman had taken a shine to the strong young Butka, and decided to give the kid a break by serving up a tantalizing assortment of fat pitches. Butka’s obvious hitting prowess convinced the usually tight-fisted Griffith to fork over a $400 signing bonus – “thanks to the generosity of Hymie Newman.”1

Contract in hand, Butka reported to the Newport Canners of the Class D Appalachian League, where he hit .332 with six home runs in 1940. Late in the season Butka was sent to the Salisbury Indians, a Senators affiliate in the Eastern Shore League. Facing a threatened players strike, the Indians needed manpower. Apparently a “misunderstanding arose over the belief of some players they would share gate receipts from the approaching playoffs.” Management researched the issue and apparently “there was no back pay due any of the players according to league rules.”2 Ultimately, the players returned to the field and captured the league championship, and Butka never appeared in an Eastern Shore League contest that season.

The Selective Service Act of 1940 required men between the ages of 18 and 65 to register for the draft; those from 21 to 36 were eligible to be conscripted into the armed services. By 1941 the eligibility range was increased to ages 18 to 45. Military physicians examined Butka and ruled him ineligible to serve because of a punctured eardrum. In 1941 the right-handed Butka patrolled first base for the Orlando Senators of the Class D Florida State League, hitting .267 with six home runs.

After the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, Butka revisited his local induction center with the renewed hope that surely he’d now be needed to help the war effort. Once again Butka was summarily dismissed as unfit for service. Resuming his baseball career, Butka started 1942 with the Utica Braves and hit Class C pitching to the tune of a.308 clip in 53 games. This performance earned him a promotion to the Springfield Rifles in the Class A Eastern League, where he hit only .199 in 73 games.

Back with Springfield in 1943, Butka improved to.298 in 133 games, earning him a call-up by Washington. Former Nats star Ossie Bluege was the Senators’ rookie manager that season; he had replaced Bucky Harris, who was fired after the team’s disappointing 1942 season. A knowledgeable baseball man, Bluege was a disciplinarian and proponent of solid baseball fundamentals. Under his tutelage, the Senators improved to second place and a respectable 84-69 record.

Butka made his major-league debut on September 26, 1943. It was the first game of a Sunday doubleheader at Griffith Stadium, pitting Washington against the Chicago White Sox. Early Wynn started for the Senators; his opponent was Ed Smith. By the top of the seventh inning, the White Sox had built up a 15-0 lead, providing Butka an opportunity to enter the game as a pinch-hitter for first baseman Mickey Vernon. Facing Smith, “The Butka kid smacked the first big league pitch he ever saw against the center field fence on the fly for a long two-bagger,”3

The Senators added single runs in the sixth, seventh, and eighth, making the final tally 15-3. For the season, Butka had three hits in nine big-league at-bats. According to Shirley Povich of the Washington Post, Bluege “was smitten with both the size and actions of the 25-year-old lad who got a chance to play in three games.”4

Good-natured Butka quickly became a favorite among his new teammates. Veteran players honored him with a special invitation to frequent the team’s closed-door poker sessions. Other young players would attempt to crash the games, only to be turned away. If they dared ask why Butka was allowed to participate, the response was generally, “We like Butka.”5 Mickey Vernon was the Senators’ regular first baseman until he was inducted into the Navy after the season, leaving Butka as the only first baseman on the roster. Clark Griffith quickly reacted and purchased the contract of former Nat Joe Kuhel. The smooth-fielding Kuhel had been a mainstay with the Senators from 1930 to 1937. Now 38 years old, Kuhel was expected to fill the position with Butka serving as his backup.

There were also possibilities at third base, a position giving Bluege headaches. During the offseason the incumbent, veteran Harlond Clift, was thrown from a horse while working his farm, resulting in a serious injury and making him questionable for 1944. Bluege entered Butka into the mix at the hot corner. “He gets around well for a big fellow, and we could use his hitting,” Bluege said. The experiment ended when Bluege realized that “Ed played third base – like a first baseman.”6

It was all hands were on deck as dugouts emptied during a contest pitting the St. Louis Browns against Washington on August 22, 1944. The fracas at Griffith Stadium ended with American League President Will Harridge fining right-hander Nelson Potter of the Browns, along with Butka and teammate George Case. The altercation started when Case successfully executed a bunt single, upsetting a rattled Potter, who had given up five consecutive hits. Name-calling on the basepaths ensued, prompting Case to nail the pitcher with a hard right to the jaw. Players on both sides charged out to join the brouhaha. “Ed Butka waded indiscriminately into the fray, seeking to make any kind of a match for himself, and was banished from the contest, along with Case and Potter, after the umpires finally restored peace.”7 The three players were each nicked with a $100 fine. Butka wasn’t even in the game at the time, but apparently charged out to assist his buddy Case. The two were close in age and had become fast friends; the friendship continued long after their careers ended.

The good-natured Butka further endeared himself to teammates, by agreeing to (gulp) a haircut, compliments of veteran teammate Johnny Niggeling. Johnny, a barber during the offseason, sat Butka down in the locker room and started to tidy up the young player. Ed likely hoped (and prayed) the hurler’s hand was steadier than his floating knuckler.

Butka eventually split 1944 between the parent Senators and the International League Buffalo Bisons. He saw action in 15 games for Washington – 14 at first base and one in which he pinch-hit, compiling a .195 batting average. At Buffalo he hit .254 in 18 games. Butka closed out 1944 on a happy note, marrying Helen Mae Meeks on November 30.

By 1945 the war was winding down and both major- and minor-league players began returning home. Butka was shipped down to the Class A Williamsport Grays in the Eastern League (.302 in 41 games) before reporting to the Triple-A Buffalo Bisons, where he hit .260 in 57 games. The Bisons traveled to play a series in Baltimore, which was the home of the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Company. The firm hosted 21 workplace teams as a means to boost morale. Wartime shortages were rampant and the dwindling supply of baseball bats curtailed playing time for company teams. Mr. Martin, a longtime baseball fan, decided to develop an improved bat based on the principles of aerodynamics.

“The final product looked at first glance just like any other bat but upon closer examination disclosed more gripping surface, a narrower lower hitting surface and a slightly tapered business end,” according to a newspaper report.8 “A little woodshop located near the plant is now turning out the bats in sufficient quantity to supply the Martin teams – and the players like them. First baseman Ed Butka of the Buffalo Bisons tried one out and liked it in batting practice, before a game in Baltimore. He used it in his first at bat and promptly hit a home run.”9

By 1946, replacement players essentially became expendable. Back home, Butka was now over 30, and he and Helen had started a family. Rather than continue a career in the nethermost levels of the minor leagues, he decided to leave the game to find work back home. In 1947 he was coaxed out of retirement to join the New London (Connecticut) Raiders in the Class B Colonial League as player-manager. The rookie manager took his club all the way to the league finals, helping out by hitting .289 in 113 games. He called it a career for good in 1948 after only 17 games (and a .259 average) with New Brunswick in the Colonial League.

Butka seguéd from the diamond into a law-enforcement career, securing a position as a police officer in his home town of Canonsburg. There, he enjoyed working with young people and became and a highly respected coach in the community. During leisure time and later in retirement, he enjoyed cooking, gardening, and golf. He was inducted into the Washington-Greene County Chapter of the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame on June 15, 2001.

After more than 60 years of marriage, Helen Butka died on March 6, 2005; Ed succumbed a few weeks later, on April 21, at the age of 89. They are buried at Oak Spring Cemetery in Canonsburg. They were the parents of five children, nine grandchildren, and 10 great-grandchildren.

Notes

1 Shirley Povich, “This Morning With Shirley Povich,” Washington Post, February 28, 1944.

2 “Salisbury Players Strike Explained,” Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times, September 9, 1940.

3 Shirley Povich, “This Morning With Shirley Povich,” Washington Post, February 28, 1944.

4 Ibid.

5 Author telephone conversation with Edward G. Butka, April 11, 2014.

6 Shirley Povich, “Fancy Player, Heavy Hitter,” Washington Post, May 5, 1944.

7 “Griff Spending to Duck Cellar,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1944.

8 “New Type Baseball Bat Developed,” Frederick Post, June 29, 1945.

9 Ibid.

Full Name

Edward Luke Butka

Born

January 7, 1916 at Canonsburg, PA (USA)

Died

April 21, 2005 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.