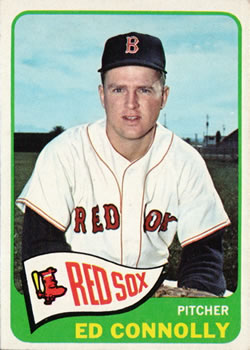

Ed Connolly Jr.

Ed Connolly Sr. was a catcher for the Boston Red Sox; his son, Ed Jr., was a pitcher for the Red Sox.

Ed Connolly Sr. was a catcher for the Boston Red Sox; his son, Ed Jr., was a pitcher for the Red Sox.

Edward Connolly Sr. had been born in Brooklyn in 1908. He played for the Red Sox 1929-1932, with a career batting mark of .178 (he garnered precisely 100 plate appearances in 1931 despite a batting average of .075 that year). Connolly never saw much duty. His best year was his last — during the nadir of the Red Sox in 1932 when the team only won 43 games all year long. Ed hit .225 and had 21 of his lifetime 31 RBIs that year. His fielding percentage wasn’t anything special at .966.

His last year in baseball was 1933, playing for Galveston. That year he married Dorothea Martha Martin in June.

Had Ed Senior lived just six months longer, he would have seen Ed Junior begin his career with the Red Sox. Junior had been born in 1939 so he never had seen his dad play, either, even when a toddler.

Like his father, Junior was born in Brooklyn, on December 3, 1939. Were he and his father backyard batterymates, as Ed Junior grew and developed into a prospect himself? Sports columnist Jimmy Murphy wrote that the elder Connolly “had groomed his son to be a big leaguer.”1

He attended St. Mary’s elementary school and St. Joseph’s High School in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst from which he received a bachelor’s degree in business administration. He was named to the All-Western Massachusetts high school baseball squad in June 1957, and pitched in American Legion baseball later that summer, winning the penultimate game in the Elkton, Maryland Eastern Sectional Tournament.

Connolly had become a pitcher, throwing left-handed. He grew to 6-feet-1, with a listed playing weight of 195 pounds. In his first start for the UMass freshman team, he threw a two-hit shutout.2 In August 1958, he pitched in the Hearst Sandlot and struck out eight batters in three innings. “Big league, just plain big league,” said Red Sox scout Fred Maguire.3 Later in August, he pitched and won a game in the National Baseball Federation tournament at Altoona.

After graduation from UMass, the Red Sox signed him to a minor-league contract on June 21, 1961, for a modest bonus. The very same week, the Sox had also signed Jerry Stephenson, son of major-league alum, Joe Stephenson.4 Connolly was reportedly signed for a $7,000 bonus.5 He might have attracted more interest but had already experienced arm troubles while pitching in college.6

His first year in the minor leagues was in 1961, for the Olean (New York) Red Sox in the Class-D New York-Penn League. He had a so-so year, working 56 innings with a record of 4-5 and an ERA of 5.95.

In late February 1962, Connolly married Rosalyn Elizbeth Zacher. He showed improvement at Olean (3-3, 3.77) so was bumped up to Winston-Salem in the Class-B Carolina League. He was 6-3 (5.10). During the year, he’d struck out 192 batters in 153 innings.

That was the year he almost quit baseball. “Arm trouble had nothing to do with my thoughts of quitting…I knew it was all right when I won the last six games of the season at Winston-Salem. But I was making only $400 a month. I was married and we were expecting a baby. The bills were piling up and I still had another semester to go to get my degree. That meant I wasn’t going to earn anything that winter. I knew I could step out of baseball and make more money than I was.”7

The Red Sox advanced him to Double-A Reading of the Eastern League in 1963. He had a 3.78 ERA with 167 strikeouts in 169 innings. His record was 7-9.

Late in 1963, Ed Senior died unexpectedly on November 12, in the woods at Pittsfield, Massachusetts — the town where he had begun his career. He was employed by the Massachusetts Natural Resources Department at the time of his death. He was survived by his wife Dorothea, a teacher in the Pittsfield public schools, and by their sons Ed Junior and Eugene.8

Reading manager Eddie Popowski was impressed with him and talked major-league manager Johnny Pesky into giving him a spring training invite. Connolly was raised a Red Sox fan, so this was the fulfillment of a lifelong dream.

Connolly’s spring training roommate was another Red Sox player to have a relative on the team — Tony Conigliaro, whose brother Billy later played for Boston. Connolly pitched himself on to the team on the strength of his spring training. Manager Pesky said, “I guess I’d have to single out southpaw Ed Connolly of Pittsfield as the most pleasant new pitching surprise of the camp…I’m quite impressed with him.”9 That he was left-handed helped; the Sox were short of lefties at the time.

Ed Junior — dubbed “The Curver” — got 15 starts from manager Pesky.Ed’s first game was April 19, 1964; the Red Sox were 2-1. He struck out six batters while walking five. He didn’t allow a hit his first three innings, then gave up a single in the fourth. So it was one hit through four innings, and he got the first batter in the fifth with a strikeout. Then the runs began. First came a perfect bunt by Don Buford, which Frank Malzone had no chance to field for an out and so let roll; it stayed fair. A single followed, and then a wild pitch let in a run. Another walk, but then came a tailor-made double play grounder to Malzone at third. The ball took an unexpected hop and went for a single, another run scoring. A squibber to the right of the mound drove in the third run of the inning and then another unintended infield dribbler brought in the fourth. There was a good bunt and one solid hit in the inning, but four runs had come across by the time it was over.

He was 0-1. Then he lost a 4-2 game in Chicago on April 25.

In the second game of the May 24 doubleheader — only his fourth appearance of the season — he earned his first win, a 3-1 win over Kansas City. He’d only lasted five innings, but it was enough. Though he’d only given up two hits, he walked six. A pair of Red Sox relievers pitched in to secure the win. It was around this time he described himself as “a three and two pitcher,” or — as Ray Fitzgerald of the Springfield Union put it, “In other words, always in trouble.”10

Five more losses followed before his second win, again 3-1, this time Connolly not giving up even one run through six innings.

There had been some tough losses, such as the 2-1 game he lost against the White Sox on August 16 when “a pair of misplayed triples and a wild pitch” cost him the game.11 Still, it was his wild pitch, and the loss was far from his first. After the game, he was 2-10.

He wasn’t getting run support. In his first 11 starts, over which he was 2-9, the Red Sox had scored a total of 15 runs — even counting runs scored in the innings after Connolly had departed from the game. In seven of the games, they’d scored either one or zero runs. It’s difficult to win a game when your team scores no runs.

On September 15, Connolly threw something of a masterpiece, a two-hit shutout of the Kansas City Athletics at Fenway. He’d given up one hit in the sixth and one in the eighth, and struck out 12.

After the game, Connolly’s foot was bleeding but, wrote Clif Keane of the Boston Globe, “it usually does.” Connolly himself explained, “I just push off the mound hard and the foot scrapes as a result.”12

He did throw the one complete game shutout, but it wasn’t an impressive year. He struck out 73 in 80 2/3 innings, but walked 64. All in all, despite a 4-11 record (his ERA was 4.91), Connolly had showed some promise, however, and Pesky had given him a fair shot.

That winter he pitched for San Juan in Puerto Rican winter ball.

The following spring, Billy Herman had become Red Sox manager and Connolly was wild in both of his preseason starts. He traveled north with the team, though, and stayed with the big-league club for a while, but April 22 he was sent down to Toronto (Boston’s International League affiliate) on 24-hour recall. Aside from a one-hitter against Syracuse on May 15, he seems not to have improved at Triple-A ball. He appeared in 22 games, starting 14 of them. He reportedly “developed a sore arm and became even wilder than he had been.”13 His ERA was 4.31. His record was 2-5. The Syracuse game was interesting in that Connolly had stepped in to bat in the seventh inning, with the bases loaded and nobody out. Toronto was leading, 4-1. Manager Dick Williams gave him the bunt sign, ordering the suicide squeeze. Connolly popped up to the pitcher, who threw to shortstop to double the runner off second base and then to third base to get the runner who had headed home. Connolly had walked seven batters in the game, but retired the last 15 Chiefs he faced.

Connolly also spent 1966 in the minors, but a rung lower on the ladder — pitching in his hometown for the Double-A (Eastern League) Pittsfield Red Sox. He was 5-10, with an ERA of 4.42. He struck out 115 batters but walked 80.

The Indians selected him in the November 1966 minor-league draft, and he reappeared in the majors with Cleveland in 1967. He started the season in the Pacific Coast League with the Portland Beavers and was a very good 6-3, with five wins in a row. He got the call back to the big leagues on June 6, and stuck with the Indians for most of the season. He posted winning records — 6-4 (3.11) for Portland, and 2-1 for Cleveland, but with a poor 7.48 ERA. He’d beaten the Orioles, 5-3, working the first eight innings on August 8. And he’d gotten the win on August 17 when he’d held the Senators scoreless in the bottom of the 15th inning, then seen his teammates score five unanswered runs in the top of the 16th.

In December his contract was sold from Portland to Seattle, the PCL club of the California Angels, but he didn’t make the big-league team in 1968 spring training, so he quit baseball. That summer, he pitched some in Boston’s Park League.

Connolly found far greater success in business. After baseball, he initially worked as an investment executive at Shearson Hayden Stone in Pittsfield, and then with Kidder, Peabody and Co. in Pittsfield. As a stockbroker with Kidder Peabody in Pittsfield, he reportedly made more money after one year than he ever had in baseball. He was promoted to manager of the firm’s Springfield office, and later manager of the company’s flagship headquarters office in New York City. After Paine Webber acquired Kidder in 1994, he rose to become a senior vice president, responsible for more than 50 investment executives serving high net worth investors.

Ed Junior died on July 1, 1998, in New Canaan, Connecticut, after suffering a heart attack while driving in his car on Route 123. He was 58. His father had died young, too, at age 55. He was survived by his wife Rosalyn and their daughters Kathy Barry and Cheryl Johnson.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Connolly’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Ed Connolly Senior’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 “Connolly Pitches Two-Hitter for UM,” Springfield Union, April 27, 1958: 23.

3 Bill McSweeny, “Connolly Fans 8 in 3 Innings,” Boston American, August 13, 1958: 43.

4 UPI, “Red Sox Sign Connolly’s Son,” Washington Post, June 22, 1961: B2.

5 Barry Stevro, Family Weekly, July 29, 1979: 19.

6 Jimmy Murphy, “Dream Comes True Too Late for Butch,” New York World Telegram Sun, May 1, 1964.

7 Tom Monahan, “Connolly Almost Quit Baseball,’ Boston Traveler, June 15, 1964: 19.

8 UPI, “Ed Connolly, Ex-Red Sox Catcher, Dies,” Boston Herald, November 13, 1963: 76.

9 “Pesky Sums Up Red Sox Outlook for 1964,” Boston Traveler, April 6,1964: 23.

10 Ray Fitzgerald, “Don’t Knock the Sox,” Springfield Union, May 28, 1964: 53.

11 Associated Press, “Misplays Aid Chicago in Win Over Bosox, 2-1,” Hartford Courant, August 17,1964: 17A.

12 Clif Keane, “Connolly: ‘I Finally Found Strike Pitch’,” Boston Globe, September 16, 1964: 39.

13 Barry Stevro.

Full Name

Edward Joseph Connolly

Born

December 3, 1939 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

July 1, 1998 at New Canaan, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.