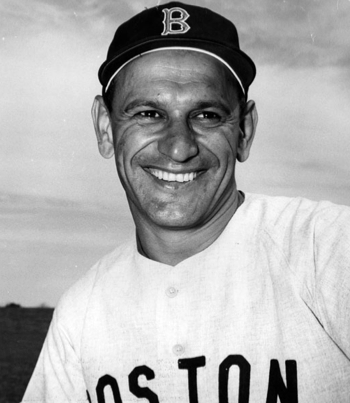

Frank Malzone

Born and raised in the Bronx, All-Star and Gold Glove third baseman Frank Malzone was a Red Sox fixture for more than 60 years, save for one season playing for the California Angels. Born on February 28, 1930, he was a Yankees fan growing up but was signed out of Samuel Gompers High School by Red Sox bird-dog scout Cy Phillips in 1947. His parents had to sign the agreement. The Red Sox paid him $175 per month as he put in his first season in professional ball in Delaware with the Milford Red Sox in the Class D Eastern Shore League, under manager Clayton Sheedy. He played in 120 games, with a .304 average that was second only to Norm Zauchin and Ray Jablonski. Milford won the league playoffs. At 18, he was 5-feet-9 and weighed in at 155 pounds, but by the time he made the majors, he’d added an inch and weighed 180.

Born and raised in the Bronx, All-Star and Gold Glove third baseman Frank Malzone was a Red Sox fixture for more than 60 years, save for one season playing for the California Angels. Born on February 28, 1930, he was a Yankees fan growing up but was signed out of Samuel Gompers High School by Red Sox bird-dog scout Cy Phillips in 1947. His parents had to sign the agreement. The Red Sox paid him $175 per month as he put in his first season in professional ball in Delaware with the Milford Red Sox in the Class D Eastern Shore League, under manager Clayton Sheedy. He played in 120 games, with a .304 average that was second only to Norm Zauchin and Ray Jablonski. Milford won the league playoffs. At 18, he was 5-feet-9 and weighed in at 155 pounds, but by the time he made the majors, he’d added an inch and weighed 180.

Malzone’s father, Frank, came to New York from Salerno in southern Italy when he was 27 or 28. Pauline, his mother, had been born in America but met her future husband during an extended visit to Italy. Frank Sr. took work with the Water Department of the City of New York. He and Pauline raised four children in New York City; “it was amazing what they did in those days, how they survived. My mother always had something great on the table.” 1

Frank first learned baseball by watching his older brother, Tony, and sister Mary play sandlot ball, for the Leland Cubs (they had an older sister Margaret, or Marge, as well). Tony played second base and Mary was the catcher, and they were charged with watching over their 9-year-old younger brother, Frankie. “They used to lug me with them when they played for the Cubs,” Frank remembered. “That’s how I learned to play and like the game. [Mary] was like a tomboy, really. She handled herself well. Line-drive-type hitter. No power.” 2

It was only in his last two years in high school that Frank played for the school team. He was studying to become an electrician, but he started thinking about playing baseball. A tryout for the New York Giants was discouraging. “You’re too small, better forget it” is what he was told. But he’d seen Phil Rizzuto play, and knew stature alone was no obstacle. 3

Not one team scouted Malzone, but bird dog Cy Phillips spotted him. Phillips knew Red Sox farm director Specs Toporcer from playing sandlot ball in Central Park. Phillips wrote Specs several times, until Toporcer sent scout Charlie Neibergall to sign Malzone. 4 During his year with the Milford Red Sox, Boston’s talent evaluators didn’t consider him a true prospect but decided to keep him “just to fill the roster.” 5

In 1949, Frank climbed a rung up the organizational ladder to Class C, playing the full year with Eddie Popowski’s Oneonta Red Sox. That’s where he met his wife, Amelia Gennerino. Amy was one of four or five girls who often came to see the games. When he saw her as he was going into a restaurant, they sat down and had a soda. Popowski was funny, Frank related. “I had to walk by his house every night to take Amy home. So first night, he waved to us. I waved. Next night, I go the same route. All of a sudden he comes across, and says to Amy, ‘Young lady, if you’re not serious about this young man, will you please leave him alone?’ He was trying to protect everybody. That was Pops.” 6

At Oneonta, Frank improved his average to .329, leading the team. Malzone’s 178 hits ranked him tops in the Canadian-American League. He hit 26 doubles and 26 triples. “I hit just about everything. I started to believe I could really play baseball. I also had a record that I think I still have in that league, the number of errors by a third baseman. I had the yips. You start aiming the ball. It took me maybe two or three weeks to get over it. Pops would say, ‘Throw the ball!’ I was doing everything else for him – knocking in big runs, hitting triples and doubles, stealing bases – I could run then. It was a complete year. If I had to name a year, that was probably my all-around best one.”

He suffered a setback in 1950, appearing in only two games with the Class A Scranton Red Sox (manager Jack Burns). In the season’s second game, he broke his leg near the ankle sliding into second base (his foot was reportedly – in Bob Holbrook’s words – “turned completely around”) and was lost for the full campaign. Burns later told The Sporting News, “I didn’t think he’d ever play ball again. The doctors thought he was through with baseball when we took him to the hospital.” 7 It was, Frank explained in his 2009 interview, “the worst thing you can have – a dislocated ankle with pulled ligaments. The doctor told me at the time that a break would have been a lot simpler. He told me, ‘It looks like you’ll be able to walk, no problem. But I don’t know about baseball.’”

When one sees Frank Malzone in his later years, he walks with an exaggerated bow-legged gait. There were signs of it early on, and it was commented on in the newspapers of the day. “My mom always said, ‘You started walking too early in life.’ I have Paget’s disease, a type of arthritis. It is, but it isn’t. Paget’s is bones growing abnormal; they get bigger than usual. And brittle.” Dom DiMaggio suffered from the same condition.

Malzone didn’t play again until 1951, but he played well for Burns at Scranton for most of the ‘51 season (he had skipped spring training because he’d been told he was going to be drafted.) Starting late, it took him a while to play his way into shape, but he hit .283 and played right up through his September 19 double play which closed out the team’s third win in the playoff finals. He’d been summoned to the United States Army. He spent all of 1952 and 1953 in military service.

Like many ballplayers of those days, Malzone had the opportunity to hone his ballplaying skills while in the service. During his initial induction interview at New Jersey’s Camp Kilburn, the sergeant asked, “How would you like to go to Hawaii for basic training?” Frank said he’d rather stay in the States. “Well, you’re going to Hawaii.” He was on his way toward Korea and the war. He had orders to ship out to the war zone, when a colonel saw he’d played minor-league baseball and changed his orders, to stay on the island at Fort Shafter.

Amy made her way to the islands. At first Frank worked as an M.P., then in a warehouse, eventually joining the Special Service, where Corporal Malzone played for the Fort Shafter Commandos. The team won 18 of its first 21 Hawaiian Armed Forces League games; Malzone starred in the 18th win with two doubles and a homer as the Commandos crushed the Pearl Harbor Marines, 14-1.

No less than Ted Williams asked Joe Cronin about Malzone, having heard about him as Capt. Williams passed through Hawaii, heading home after his 39 combat missions in the Korean War. “Who’s that spaghetti-eater you got out in Hawaii?” Williams asked Cronin. “I stopped in Hawaii on my way back to the States and that’s all I heard. Everybody was talking about Malzone. Must be a pretty good ballplayer.” 8 Malzone played about 60 games a year, largely against other pros. Tommy Fitzgerald’s spring training report in The Sporting News portrayed “a short, bow-legged fellow … a cat-like third baseman who got the ball away quickly.” 9 He played some shortstop in the Army, figuring versatility would be an asset.

When Frank returned to organized ball, in Triple A with the 1954 Louisville Colonels, he’d missed three of the preceding four years. Manager Pinky Higgins worked him out at second base, too. “Malzone has a quick throw. He ought to be able to get the ball away from him fast on double plays.” 10 Malzone hit .270 his first year in Triple A – playing third base. He had a disappointing Little World Series; though the Colonels beat the Syracuse Chiefs in six games, Malzone hit .only 111 and committed seven of Louisville’s 10 errors. After a daughter, Suzanne, was born, Frank played for the Ponce Lions, ranking in the top 10 for batting average in Puerto Rican winter ball.

Frank’s first spring training with the parent club was in 1955. After Higgins’ success with Louisville, he became the big-league manager. The Colonels had a team sporting six bonus babies (Don Buddin, Jerry Casale, Dick Gernert, Marty Keough, Haywood Sullivan, and Joe Tanner) but Frank Malzone shone the brightest in Louisville – despite having signed initially for little more than $40 a week. He increased his average to .310, was named to the American Association All-Star Game, and became a mid-September call-up who debuted in major-league baseball on September 17 – as a pinch runner.

Malzone’s first start was on September 20, and he played both games of a doubleheader in Boston. Frankie made an immediate impression, going 4-for-5 in the first game (with a double) and 2-for-5 in the second game, while notching his first run batted in. He saw action in six games, hitting .350, but didn’t play in a Red Sox win for more than half a year – the Sox lost every one of those 1955 ballgames.

The Malzones had added a son, Jimmy, to the family but, tragically, lost 15-month-old Suzanne to illness over the wintertime. Frank made the 1956 team out of spring training. Higgins was high on him, telling the Christian Science Monitor’s Ed Rumill, “Frank could be one of the big surprises of the season. … You won’t see a better arm anywhere. He won’t be great today, bad tomorrow. He’ll do the job every day. … Frank has good power. Not long-ball power. He hits stingers – line drives in between the fielders. He’ll get his share of extra-base hits. He might hit a few out at Fenway Park, too.” 11 Malzone played through June 5, getting into 27 games (he drove in the seventh run in the 8-1 victory in his first game). He hit a couple of home runs, but come early June, he had hit only one single in his last 33 at-bats and was hitting .165. It seemed advisable to send him to San Francisco, but even that didn’t help at first. The loss of his daughter was still weighing heavily on him, suggested Hy Hurwitz. 12 In The Saturday Evening Post of April 12, 1958, Al Hirshberg said it was only some months later, after consulting their parish priest, that Frank and Amy first talked it through. Amy said, “Everything that Frankie had been holding in came spilling out.” After that, Malzone began to come back as a player. He credited the importance of the priest and, as well, Seals manager Joe Gordon. He played out the rest of the year on the West Coast, batting .296 for the Pacific Coast League’s Seals. He ended the season well, entering the last week riding an 18-game hitting streak and hitting a grand slam on September 7. After that, Frank returned to winter ball in Puerto Rico, playing for Ralph Houk and the San Juan Senators.

Frank and Amy added four more children to the family: Paul, Frankie, Anne Susan, and John. “John was the surprise one,” he said. After they settled in to setting up a home in Needham, Massachusetts, Amy devoted much of her spare time to volunteer work in the local hospital. “She loved people,” Frank said. “She was well thought of in the town.” Amy died in January 2006, and Frank remained in the house he had built for the family in 1965, counting eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. John Malzone, born 17 days after the 1967 World Series, was the only one to try his hand at professional baseball. He put in seven seasons in the Red Sox system, almost exclusively at third base, but had little success above Single-A.

Returning to 1957, Frank could no longer be denied. He made the Red Sox team for good, and was fortunate that Higgins stuck by him in the early going. By May 8, he was hitting an even .300 and opponents learned to respect him. By June 23, he was hitting .322 – better than any other major-league third baseman – and flashing the glove, too. On July 4, he was the first American Leaguer to reach 100 hits. Orioles third baseman George Kell, selected to start the All-Star Game, declared, “I don’t deserve it. … This Red Sox kid is great, really great. He should have gotten it.” American League manager Casey Stengel named Frank as a reserve, and he spelled Kell at third. Both players were 0-for-2 in the game. In his first full season, Frank Malzone was an All-Star.

By season’s end, he ranked 10th among all American Leaguers with his .292 average. His hitting was productive; his 103 RBIs ranked third in the AL (in a three-way tie with teammate Jackie Jensen and Minnie Minoso). Because he had had 103 at-bats in 1956, he was ruled ineligible for Rookie of the Year voting – but still came in second (one maverick voter cast a ballot for him anyway, while the other 23 voted for Tony Kubek). The voting followed a month-long controversy over what the criteria should be for ROY. Malzone was voted as the top sophomore, so named on 166 of 182 ballots; Luis Aparicio was second, with 14 votes. For his part, Malzone just said he was happy to have made the grade in the major leagues.

Malzone led the American League in total games, and led third basemen in chances, assists, and double plays. It was no surprise that he was named the major leagues’ Gold Glove winner at third base. Starting in 1958, each league awarded a Gold Glove – and Malzone won again in both 1958 and 1959. Malzone burst on the scene like – in Hy Hurwitz’s words, “a delayed-action bomb.” He was such a quiet, modest, and unassuming ballplayer that Red Sox traveling secretary Tom Dowd averred, “If he wasn’t on the roster, I wouldn’t know he was on the club.” 13

“He’s no flash in the pan,” said manager Higgins, looking forward to 1958, going so far as to say, “He’s played the best third base of any Red Sox player ever.” 14Malzone started 1958 slowly, hitting under .200 through April 27 (he later blamed it on not taking off enough offseason weight) — but picked it up and posted similar totals to 1957: slightly higher in average (.295), and with 87 RBIs, good for seventh in the league. Frank made the All-Star squad again, and captured the Gold Glove. After just two seasons, he was already a fixture at the hot corner. After the season, Frank took up work with a local tire company in Needham.

His goal for 1959 was to hit .300. He didn’t make it; in fact, he declined to .280, though he boosted his homers from the 15 he’d had each of his first two years up to 19 and bumped his RBI total up to 92. Another All-Star Game (a “defensive standout,” wrote The Sporting News) and another Gold Glove. He started out stronger, and was over .300 through almost all of May but then cooled off just a bit and was very consistent around .280 for the rest of the season. “Slumps are caused just by being lazy with the bat,” he explained regarding the ‘57 and ‘58 campaigns. Now, it seemed, he’d found his level. He never did hit .300, and wound up with a lifetime .274 average. He didn’t miss a game from May 21, 1957, to June 7, 1960 – 475 consecutive games.

Malzone later admitted he may have tried too hard to be an iron man. 15 He had a bit of an off-year in 1960; in ‘61, he bumped up his RBIs by eight, but his average fell another five points.

With Ted Williams on the way out, and Carl Yastrzemski not established yet, it was an in-between time for the Red Sox and there wasn’t the protection in the lineup that benefits a good hitter. In 1960, Malzone was almost the only right-hand hitter with any power. Only Vic Wertz, a left-handed hitter, had more RBIs than Malzone. In 1961, an ankle injury caused him to miss most of the first week of the season, but by year’s end his 87 RBIs were seven more than the next-closest Red Sox batter, rookie Yastrzemski. Frank led Yaz again in 1962, batting in one more run than Yaz’s 94 – but Yaz scored 99 to Malzone’s 74. Frank’s biggest play of the year may have been the eighth-inning foul ball he caught on June 26, saving Earl Wilson’s no-hitter, a backhanded grab right at the top of the Angels’ dugout. Malzone also hit 21 homers in 1962, a career high. A month later, Malzone was hurt in Yankee Stadium and missed three games, the first games he’d missed all season.

Malzone made another run at .300 in 1963 – batting as high as .345 on July 1, before dipping in the final two months to .291. Playing for new manager Johnny Pesky, the “old pro,” he was now 33, and had been seen as the veteran player for a few years. “I guess I’m getting lucky in my old age,” he told Tom Monahan in mid-May. 16 After pitcher Ike Delock was released, Malzone become the longest-tenured player with the team. One of his more thrilling contributions of the year was the three-run homer he hit in the top of the 15th inning against Detroit on June 11. He had missed out on the All-Star Game in both ‘61 and ‘62, but his hot start in 1963 – the best of his career – saw him named to the squad once again. Patience was paying off. “You get smarter, and as you do you gradually break yourself of the habit of going after bad balls,” he told Ed Rumill of the Monitor. 17

Pesky was fired just before the end of the 1964 season. The promising start he’d had in 1963 failed to hold up and the ballclub plunged in the standings, finishing in seventh place in ‘63 and eighth place in 1964. Malzone hit .264 in 1964 and drove in what was at that point a career-low 56 runs. He did make the All-Star squad again, for the last time. Larry Claflin wrote that Malzone was “in the twilight of a fine career” and that “time is taking its toll.” 18In 1965, Malzone got less work, down to 400 plate appearances in 106 games. There was one stretch from May 13 to June 18 in which he failed to get an extra-base hit. His first home run of the year didn’t come until August 1. By early September, there was talk that it might be Malzone’s last year with the Red Sox – and Yaz spoke up, saying how much time Frank had put in working with possible heir-apparent Dalton Jones, helping Jones with his fielding – even though it might cost him his own job. 19For the season, Malzone hit just .239 with 34 RBIs.

Tom Yawkey finally got rid of general manager Mike Higgins, selecting Dick O’Connell as his replacement. On November 19, 1965, the Red Sox gave Frank Malzone his unconditional release, O’Connell said, so that Frank could try for a shot with another team. O’Connell added that a position would be waiting for Malzone in the Red Sox organization. 20 The release helped cut salary, too, since Malzone’s estimated $35,000 a year was one of the highest on the team. Frank signed with the California Angels the very day he passed through waivers – November 30. Angels general manager Fred Haney signed Malzone, 35, Lew Burdette, 38, and Norm Siebern, 32, promoting a headline, “Angels Accused Of Operating an Old-Folks Home.” 21 “He could be the best pinch hitter we’ve ever had,” said manager Bill Rigney. He wasn’t, though he did hit a couple of key homers in June. In his last year as an active player, Malzone hit .206 in 155 at-bats, appearing in 82 games and driving in only 12 runs. The Angels released him in October.

O’Connell gave Frank the choice of becoming a minor-league manager, a hitting instructor, or a scout. Malzone found they paid about the same, but scouting in the New England area afforded him the opportunity to be home more often. “I looked at players, but I never signed anybody; I always called Jack Burns and he handled it.”

Frank worked all year learning the ropes while scouting around New England with area scout Burns. Come September, Frank served as advance scout, following the Twins in the race to the pennant. He then moved on to scout the NL champion Cardinals. Sox manager Dick Williams was very pleased. “Malzone gave us a terrific scouting report on the Twins for the weekend games. … We have a pretty good ‘book’ on St. Louis.” 22In 1967, many credit Malzone’s work as an advance scout for seeing the Red Sox go as far as they did that year – all the way to Game Seven of the World Series.

At the end of 1969, new Sox manager Eddie Kasko disappointed Malzone by choosing Don Lenhardt as one of his major-league coaches; Frank had wanted the job. But his position with the club was secure. For 28 years, Frank worked in advance scouting for the Red Sox. He also helped with instructional work, too, for instance working closely with Rico Petrocelli in the spring of 1971, when Rico transitioned from shortstop to third baseman.

The courtesies typically accorded scouts were not always observed. When the Red Sox were playing the Athletics in the 1975 playoffs, Oakland owner Charlie Finley had Malzone barred from the press dining room. Dick Young wrote, “Not even a cup of coffee, said Charlie O. for the man who was spying on his ball club.” 23 Just as he’d worked with Rico, Frank worked as an instructor in the springtime with future Hall of Famer Jim Rice – as did Johnny Pesky — hitting him ball after ball in 1980 so Rice could work on his fielding. “He had trouble with ground balls and had me hit him 50 to 100 a day,” Malzone said. ”He’ll get into the habit of coming in on the ball rather than waiting for it to come to him.” 24

Frank’s springtime instructional work ended with the 1992 season, as did fellow instructor Sam Mele’s. After the 1994 season, Mele accepted an early retirement offer. Malzone was “kicked upstairs” to work as an assistant to new general manager Dan Duquette. For the most part, his scouting work was over. “I ended when Kevin Kennedy was manager in 1995. Dan Duquette was the general manager. He wanted me to be an advance guy. I took over and I did it for about two months. I told Kevin I’m getting a little old for all this traveling. If possible, I could work with another guy and split it.” He would have shared the work with Jerry Stephenson from the West Coast. “But Duquette said he didn’t think it was a two-man job. He wanted it to be a one-man job. He asked Jerry to handle it.” Yet, Frank is by no means a Duquette detractor. “I got along better than anybody with Dan Duquette. We just had a rapport. He called me and talked with me more than any general manager through the years. He loved to talk about baseball. He knew I was going to be honest with him. I wasn’t going to say something so he’d like me.”

Scouts today, he says, “don’t watch the ballgame. They go out to the ballpark and all they’re doing is taking notes. Notes, notes, notes. I don’t consider it scouting because you don’t get a feel for the ballplayer. I like to get a feel for a ballplayer. That’s the way I scouted. It worked for me through a lot of managers – Eddie Kasko, Ralph Houk, Don Zimmer, McNamara, Joe Morgan … .”

He’s seen a lot of changes, and wishes he’d had some of the tools players have today. Although Dick Williams just began to use video in the spring of ‘67, for instructional purposes, Frank said, “I’d love to have had the videos they have today, when I’m playing. We had to keep it in our head. How’d this guy pitch the last time I faced him. Now all they have to do is walk into the other room and look it up.” 25

Frank Malzone was one of the inaugural class of inductees into the Red Sox Hall of Fame, in November 1995. Even into 2011, Frank Malzone remained on the Red Sox payroll as a “player development consultant.”

Postscript

Malzone died on December 29, 2015, in Needham, Massachusetts.

Notes

1 Frank Malzone, interview, August 18, 2009.

2 Ibid.

3 Christian Science Monitor, September 13, 1957.

4 The Sporting News, September 11, 1957.

5 The Sporting News, June 15, 1963.

6 Malzone.

7 The Sporting News, March 16, 1955

8 The Sporting News, April 7, 1954

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Christian Science Monitor, April 3, 1956.

12 The Sporting News, February 20, 1957, and September 11, 1957.

13 The Sporting News, September 11, 1957.

14 The Sporting News, April 2, 1958.

15 The Sporting News, February 22, 1961.

16 The Sporting News, May 23, 1963.

17 Christian Science Monitor, June 21, 1963.

18 The Sporting News, November 28, 1964.

19 The Sporting News, September 4, 1965.

20 Hartford Courant, November 20, 1965.

21 The Sporting News, December 18, 1965.

22 Boston Record American, October 4, 1967.

23 The Sporting News, October 25, 1975.

24 The Sporting News, April 26, 1980.

25 Frank Malzone, interviews, October 4 and 16, 2006.

Full Name

Frank James Malzone

Born

February 28, 1930 at Bronx, NY (USA)

Died

December 29, 2015 at Needham, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.